But go ye now unto my place which [was] in Shiloh, where I set my name at the first, and see what I did to it for the wickedness of my people. —Jeremiah 7:12

[dropcap]B[/dropcap]efore it lent its name to the April 6-7, 1862, battle, Shiloh Church was the center of a community. Erected in 1851, the humble church sat at a small crossroads in heavily wooded tableland three miles west of the bend in the Tennessee River where waters that have run all the way from the Appalachians cease their westward track across the top of Alabama and plunge due north, back into Tennessee and all the way to the Ohio River.

Growing up around Shiloh Church, Elsie Duncan remembered her community as an idyll in the woods. The forest was beautiful, she said, “with every kind of oak, maple and birch, [with] fruit trees and berry bushes and a spring-fed pond with water lilies blooming white.” As the 9-year-old daughter of Shiloh’s circuit-riding minister, Elsie knew the woods well. On the morning of the battle, she remembered that “the sun was shining, birds were singing, and the air was soft and sweet. I sat down under a holly-hock bush which was full of pink blossoms and watched the bees gathering honey.”

Disembarking at Pittsburg Landing, many of Ulysses S. Grant’s soldiers saw not an idyll but a muddy, squalid waste, which, in fairness, Shiloh also was. “Pittsburg Landing…excited nothing but disgust and ridicule,” said one Federal. “A small, dilapidated storehouse was the only building there.” The surrounding area was “an uninteresting tract of country, cut up by rough ravines and ridges, [where] here and there an irregular field and rude cabin indicated a puny effort at agriculture.”

The Federals were equally unimpressed with Shiloh Church—a “rude structure in which…the voices of the ‘poor white trash’ of Tennessee mingle in praise to God.” “It is not such a church as you see in your own village,” one New Englander explained: “It has no tall steeple or tapering spire, no deep-toned bell, no organ, no singing-seats or gallery, no pews or carpeted aisles. It is built of logs…chinked with clay years ago, but the rains have washed it out. You can thrust your hand between the cracks [making it] the ‘best-ventilated’ church you ever saw.” Such estimations drip with class bias. They also drip with judgment.

The Federals knew that Shiloh Church was proslavery, pro-Confederate. It was formed after the great schism in the Methodist Church in 1844, when, ironically, the local proslavery congregants fled a church called “Union” to form their own church west of the river. To many of the invading Federals, Shiloh Church was a perversion—“a little log building in the woods,” said one, “where the people of the vicinage were wont to meet on the Sabbath and listen to sermons about the beauties of African Slavery.” Reading their Bibles, such Yankees had decided that God demanded a rough equality—no man should be a master; no man should be a slave. Reading the same Bible, the Duncans and their neighbors had concluded that God had fitted an entire race for slavery—whites had been chosen, blacks had not.

I have often wondered whether, in naming their church Shiloh, the parishioners knew what they were letting themselves in for biblically. Certainly they knew their Bible better than I. Then again, they didn’t have Google. “Shiloh” is typically translated as “Place of Peace”—which is, let’s face it, the kind of irony Civil War historians and the public find irresistible. But before Shiloh was a “town” in Elsie Duncan’s west Tennessee, it was a city in ancient Samaria. As the Book of Jeremiah tells us, the ark of the covenant resided there for untold years before the locals, somewhat typically, ran afoul of the Almighty. And so did God smite Shiloh in a biblical bloodletting intended to serve as an example to the Israelites of how lucky they were to be merely enduring the Babylonian captivity: “Therefore thus saith the Lord God; Behold, mine anger and my fury shall be poured out upon this place, upon man, and upon beast, and upon the trees of the field, and upon the fruit of the ground; and it shall burn, and shall not be quenched.” “Shiloh” is probably correctly translated as “Place of Peace,” but it could also be translated as “Place of Desolation.”

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]n his memoir, Grant said that Shiloh “has been perhaps less understood, or, to state the case more accurately, more persistently misunderstood, than any other engagement between National and Confederate troops during the entire rebellion.” Grant had a vested interest in saying so: most observers at the time believed that he had made grave mistakes there. To his everlasting credit and occasional shame, Grant was doggedly offense-minded, and by his own admission, prior to Shiloh, he had never quite considered the possibility that he might be attacked. “Contrary to all my experience…we were on the defensive,” he said of the opening action on April 6, “without intrenchments [sic] or defensive advantages of any sort.” This might seem to implicate him as a commander, but he said he had decided that his men were so green they needed drill more than trenches. Probably they needed both. Certainly I agree with a Confederate officer’s assessment that Grant’s position “simply invited attack.”

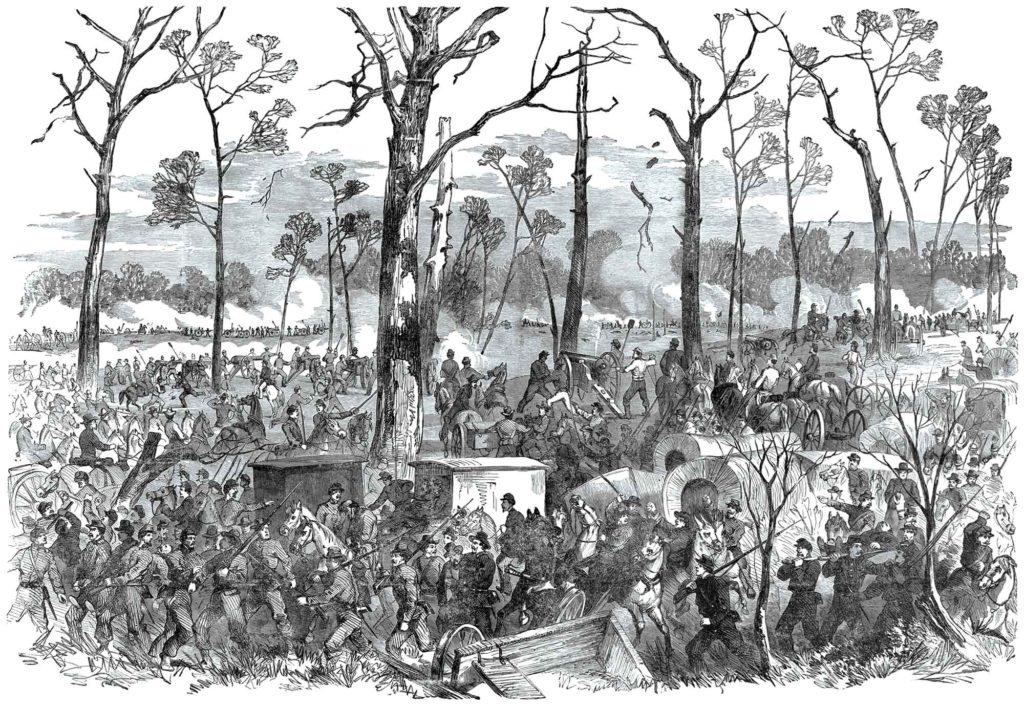

Leading the Confederates, Grant’s antagonist, Albert Sidney Johnston, had a bad first day too—not least because he was mortally wounded. Most historians regard Johnston as more or less complicit in his own undoing, for having sent off his surgeon and for generally leading from the front. The truth, however, is that Grant and William Tecumseh Sherman had close calls at Shiloh also. It was that kind of fight. As one soldier remembered, the bullets seemed to come “from too many points of the compass.” “A man who was hit on the shin by a glancing ball…[was] hurt…awfully,” the soldier continued, “and he screamed out. His captain said, ‘Go to the rear.’ As the line broke and began to drift through the brush, this soldier came limping back and said, ‘Cap, give me a gun. This blamed fight ain’t got any rear.’”

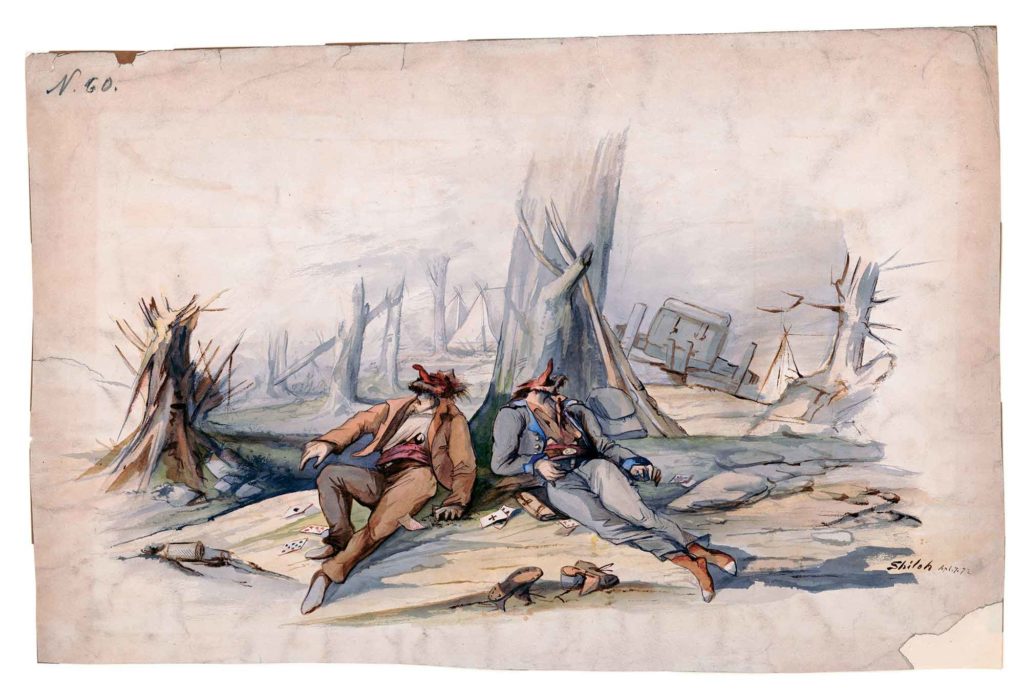

The sense of chaos at Shiloh was undoubtedly amplified by the terrain. “I had always supposed, from pictures I had seen, that armies were drawn upon each side of a big field,” noted one Federal. “I didn’t understand how we could fight in those woods.”

Many of them did not fight very well. Grant admitted that most of his men were “entirely raw…hardly able to load their muskets according to the manual.” “In two cases, as I now remember,” he later said, “colonels led their regiments from the field on first hearing the whistle of the enemy’s bullets.”

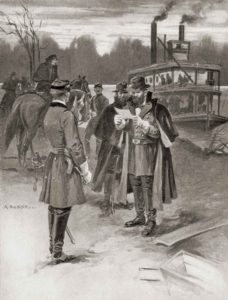

At Shiloh, many officers were so green, they didn’t even know what their generals looked like. Colonel H.T. Reid was approached by a stranger who said gruffly, “After the men have had their coffee and received their ammunition…move [them] to the top of the bluff and stop all stragglers and await further orders.” Reid stared at the man blankly for a moment before the stranger satisfied his curiosity: “I am General Grant.” Another officer requested ammunition from a stranger “with stars on his shoulders” who sat on his horse as a king might a throne. “I [do not] believe you want ammunition, sir,” the latter said furiously. “I looked at him in astonishment, doubting his sanity,” the officer noted, “but made no further reply than to ask his name.” “It makes no difference, sir,” came the reply, “but I am General Buell.”

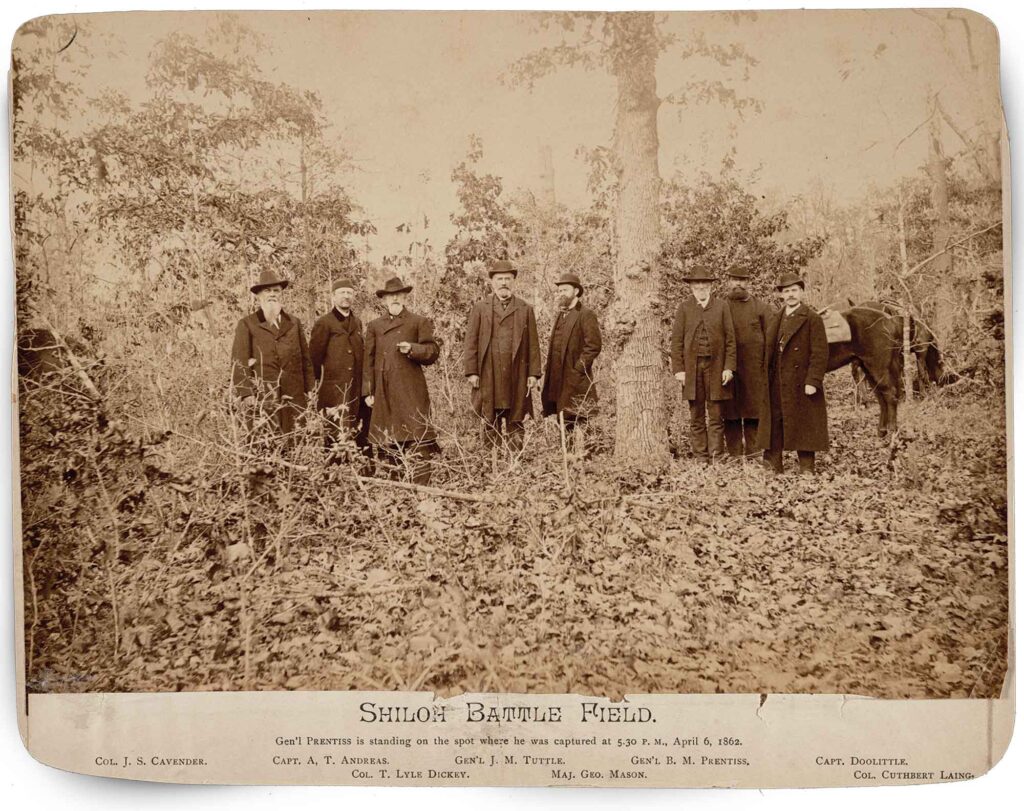

Such mix-ups are amusing. They could also be deadly. After his heroic holdout at the Hornets’ Nest, Union Brig. Gen. Benjamin Prentiss tried repeatedly to surrender, but every time he successfully did so new Rebels would emerge from the woods and fire on his men even after being ordered to stand down. As one survivor remembered, “The firing did not cease until General Prentice [sic] told the rebel officers that if they did not stop, he would order his men to take their guns and sell their lives as dearly as possible.”

Where their greenness most showed was immediately after the battle, when they got their first look at the carnage. “They were mangled in every conceivable form,” said one soldier. They were “torn all to pieces,” said another, “leaving nothing but their heads or their boots.” “They were mingled together in inextricable confusion,” said a third, “headless, trunkless, and disemboweled.”

There is a problem in Civil War history that I will dub the “problem of gore.” Those of us who have written a lot of Civil War history inevitably face a conundrum: When it comes to the material realities of the battlefield, how much is “enough”? Do I really tell my audience that, at the end of day one, Shiloh’s spring dogwoods, in full bloom, are festooned with arms, legs, and entrails? Is that gratuitous? Or is it necessary?

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]They were mingled together in inextricable confusion…headless, trunkless, and disemboweled.[/quote]

There are few bills I would not pay for my country to have ended slavery even a year sooner. There were generations of black children who never went to school, a vast industry of commodified human beings, endemic rape, and leveraged sex, all of which is humiliating and painful to look upon as an American. Surely ending all of this—surely emancipation—“redeemed” this conflict.

And yet there are images of Shiloh I can’t get out of my head: the wounded Federal who lay strewn across a log, legs on one side, body on the other, conscious but immobile as fire crept across the leaf litter to ignite the log, burning his legs from his body but leaving his smoking feet on one side and his still-breathing torso on the other.

Or the Confederate, bayoneted through the temple, eye distended, lying in a state of madness, pulling on his eye stalk: “He seems unconscious, and yet he has not lost sensation. He evidently received a bayonet thrust in his temple which caused the eye on that side to bulge out of its socket, and he has pulled at it till the optic nerve is out at full length. How it pops when the eyeball slips out of his hand. He has pulled at it till the optic nerve is real dirty; and from the delicate structure of the eye and its connection with the brain, we know he must suffer fearfully.”

Am I really supposed to elide this? Am I supposed to edit this out because I am told that it is gratuitous, sophomoric, gauche, or unpleasant? Perhaps I am. But who exactly decided that reading about war should be pleasant? When Oliver Wendell Holmes said of the Civil War generation, “In our youth our hearts were touched with fire,” I think what he really meant was that “In our youth our retinas were burned with images that would never let us go.”

[dropcap]O[/dropcap]n his second day at Shiloh, Mississippian Augustus Mecklin was awakened at midnight by orders to fall in. The rain was coming in torrents and the darkness was so intense he could barely see the officer leading him into position. Every so often, however, “vivid peals of…lightning” would ignite the landscape, searing Mecklin’s mind with one appalling image after another: first a “dead man, his clothes ghastly, bloody face turned up to the pattering raindrops,” then his friend slipping upon a corpse that lay dismembered in the road, then a Golgotha of “dead, heaped & piled upon each other.” How, Mecklin wondered, had men so quickly taken a beautiful “Sabboth morn” and rendered it an infernal hell-scape where “monster death” held “high carnival”?

Civil War Americans were very articulate when writing about horror. Walt Whitman embodies that conclusion. Traveling to Fredericksburg to nurse his wounded brother, he discovered that his brother was fine. But Whitman was never the same: “These thousands, and tens and twenties of thousands of American young men, badly wounded, all sorts of wounds, operated on, pallid with diarrhea, languishing, dying with fever, pneumonia, &c. open a new world somehow to me, giving closer insights, new things, exploring deeper mines than any yet, showing our humanity…tried by terrible, fearfulest tests, probed deepest, the living soul’s, the body’s tragedies, bursting the petty bounds of art.”

With all due reverence for Whitman’s style, I think what he is saying is that the real war will never get into the books until we figure out how to grapple deeply with the violence. I entirely grant that the men and women of the Civil War era had an extraordinary tolerance for other people’s pain. Some of them could make fun of a dying man, wave at people with a dismembered arm, or boil a dead man’s bones to make jewelry. But it is cavalier to think that the national bloodletting didn’t affect them deeply or that behind their occasionally feeble metaphors—“corpses stacked like cordwood” and “hails of gunfire”—there wasn’t an ocean of feeling being poured out in a puddle of blood. “As if the soul’s fullness didn’t sometimes overflow into the emptiest metaphors,” Flaubert once explained, “for no one, ever, can give the exact measure of his needs, his apprehensions, or his sorrows; and human speech is like a cracked cauldron on which we bang out tunes to make bears dance, when we want to move the stars to pity.”

Of all the battles fought in the Civil War, I have always thought that tragicomic Shiloh had the best chance of moving the stars to pity. Rightly and wrongly, the Civil War stands as an American Iliad; each of its battles has been translated into a mythic character and asked to play a specific part in a national morality play. Gettysburg stands as the great test of democracy, the darkest hour in a national struggle to determine whether “any nation so conceived, and so dedicated, can long endure.”

Shiloh may be equally fabled and fabulous, but the moral is different. Shiloh represents the death of national innocence. On an idyllic spring Sunday in America, war took an Edenic field of dogwoods and peach blossoms and painted it with gore.

[dropcap]W[/dropcap]ars may be fought outside, but they are made inside—in the halls of Congress and the White House, in parlors, kitchens, and churches. Elsie Duncan’s father may have been a preacher, but he was also the community’s drillmaster. “He would prepare our young men to go into the army to fight other men that they did not even know, nor have anything against,” Elsie Duncan later marveled. “I used to sit and watch them go marching by and I wondered how many of them would be killed.” Duncan’s final time inside Shiloh Church was when she performed in a concert. She enacted a skit in which the South was the goose that laid the golden egg, but Lincoln squeezed it too hard and it ran away. The girls waved Confederate flags and sang “Dixie.” The men threw “their hats up yelling, ‘hurrah for Jefferson Davis and the Southern Confederacy.’ How that old Shiloh Church did ring.”

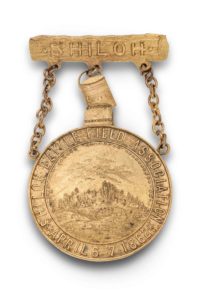

Shiloh Church was everywhere in the battle. At different times, it served variously as headquarters for both armies, a hospital, a prison, and a morgue. Albert Sidney Johnston’s body was carried to the church for a time. At the church, P.G.T. Beauregard, Johnston’s successor, decided not to follow up on the gains of April 6, giving Grant a chance to rally and recapture the church the next day. And while the church was not killed on the field, it was certainly a casualty. In the days and weeks after it gave its name to the battle it was torn down for firewood, bridges, and especially souvenirs. “No one who visits Pittsburg Landing has a thought of returning without first making a pilgrimage to Shiloh Church,” noted one newspaper, “and few have returned without bearing home with them ‘a piece of the church as a trophy.’ Shiloh Church is now in ruins.”

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]Shiloh represents the death of national innocence[/quote]

Shiloh Church got what it deserved, I suppose. But I am glad it has been reconstructed as part of the effort to restore and preserve the battlefield. I like to think that people will sit there, contemplating hubris and confronting the fact that we are a sometimes hardheaded, hard-hearted, misguided people. We are tenderhearted, too, and capable of redemption. “When I came to,” wrote one wounded soldier at Shiloh,

I found my gun gone and the fellows around me saying it was no use taking [me] off the field. [I had] gone up at the spout….I had not the courage to open my eyes. My first movement was to feel if I still lived….Every action of my life seemed written before me. When I opened my eyes the battle was still going on, and many had bit the dust like myself. I put my hand to my head where I remember having been struck, for I felt no pain, and my hand, when I looked at it, told a fearful story, and [I] felt the warm blood running down my back in a perfect stream….While drooping in this way, my head leaning against the tree, I noticed a little violet looking up to me from under the trampled grass, and a thought of past scenes of a different nature passed through my mind as I plucked it and put it in my sketchbook next to my bosom….The little flower I carefully kept and pressed in my journal was the only trophy I took from the fire of battle.”

Stephen Berry is Gregory Professor of the Civil War Era at the University of Georgia. His books include All That Makes a Man: Love and Ambition in the Civil War South (2003) and House of Abraham: Lincoln and the Todds, a Family Divided by War (2007). This article is adapted from Civil War Places: Seeing the Conflict Through the Eyes of its Leading Historians, edited by Gary W. Gallagher and J. Matthew Gallman, © 2019 by Gary W. Gallagher and J. Matthew Gallman. Used by permission of the University of North Carolina Press. www.uncpress.org