“It ought to be solemnized with pomp and parade, with shows, games, sports, guns, bells, bonfires, and illuminations, from one end of this continent to the other, from this time forward forever more,” John Adams wrote to his wife, Abigail, on July 3, 1776.

For 245 years the Fourth of July has been synonymous with hot dogs, red, white, and blue outfits purchased from Old Navy, and fireworks. Lots and lots of fireworks. Precisely as our Founding Father predicted.

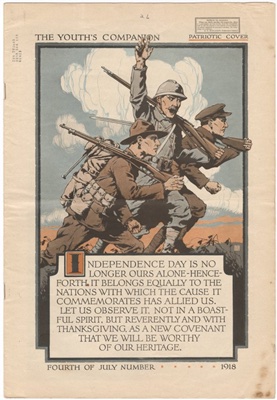

But in 1917, as war continued to rage on the Western Front, the newly arrived American doughboys expected little pomp and circumstance to mark their nation’s independence.

However, leave it to the nation’s oldest ally, the French, to throw a party.

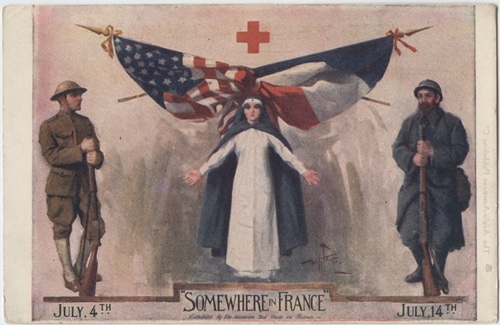

French soldiers and citizens gathered across the country to celebrate the American holiday while U.S. troops marched through Paris as crowds of people cheered them on, according to the National World War I Museum and Memorial.

The following year the celebrations were even more grand, with a ceremony being held to rename Avenue du’Trocadero after President Woodrow Wilson.

“There was a warmness there. Roughly a third of [France’s] male population between the ages of 18 and 35, died in the first few years of the war,” Lora Vogt, Curator of Education at National World War I Museum and Memorial, told HistoryNet. “So anyone else who’s willing to come in and help defend their nation… I would say that most French were quite pleased that the Americans were coming in to be a bulwark.”

After three long years of brutal fighting, the U.S. entrance into World War I all but spelled defeat for the Germans. Only a mere three months after President Woodrow Wilson asked Congress to declare war on the Central Powers American boots were on French soil.

That gratitude played out in the embracing America’s day of independence from the seats of both the Allied governments — King George ordered that the American Flag fly from Victoria Tower to mark the Fourth of July — on down to ordinary civilians.

“You’ve got King George attending a baseball game between the US [Army] and the Navy teams… At a local level they’ve gotten to know these soldiers, because these guys are coming over and having meals at the neighborhood café,” said Vogt. “There are these really beautiful letters on how relationships were built. An appreciation on a family-by-family level is really what you see in a lot of letters.”

Throughout the beleaguered French nation, impromptu celebrations cropped up to mark American independence, with one American soldier remarking in a letter home dated July 8, 1917, “Whenever one sees a French flag, there is an American flag.”

“You have this embracing of Americans for what they bring and it’s a time where they begin to really identify themselves in the 20th century,” said Vogt.

But unfortunately, the embracing of American culture only went so far. Despite the doughboys best efforts, the culinary marvel that was and is a hot dog never caught on.

More’s the pity. Happy 4th, all!