Submarine warfare comes to Massachusetts beach town in 1918

NUMBER ONE SURFMAN William Moore of U.S. Coast Guard Station 40 peered into the mid-morning haze and mopped his brow. Sunday, July 21, 1918, had dawned hot and humid at Orleans, Massachusetts, on the shore of Cape Cod. The Cape resembles a flexed arm jutting into the Atlantic, with Orleans at the outer elbow. The usual breezes were absent, leaving conditions uncomfortably close even at seaside. Monitoring passing vessels and aiding any in distress was the duty assigned Moore and five other men on duty at Station 40. From his tower, Moore watched as a tug and its retinue hove into view.

The 120-foot Perth Amboy was bound for the Virginia Capes, towing four barges. Just before 10:30 a.m., one of the tug’s deckhands saw a white object skip through the water toward the vessel,

passing wide at the stern. On the beach at Orleans, something exploded, sending sand and seawater cascading with a roar like thunder that confused residents—no one was expecting rain, or that in the next 90 minutes Orleans would be the unintentional target of a German submarine attack.

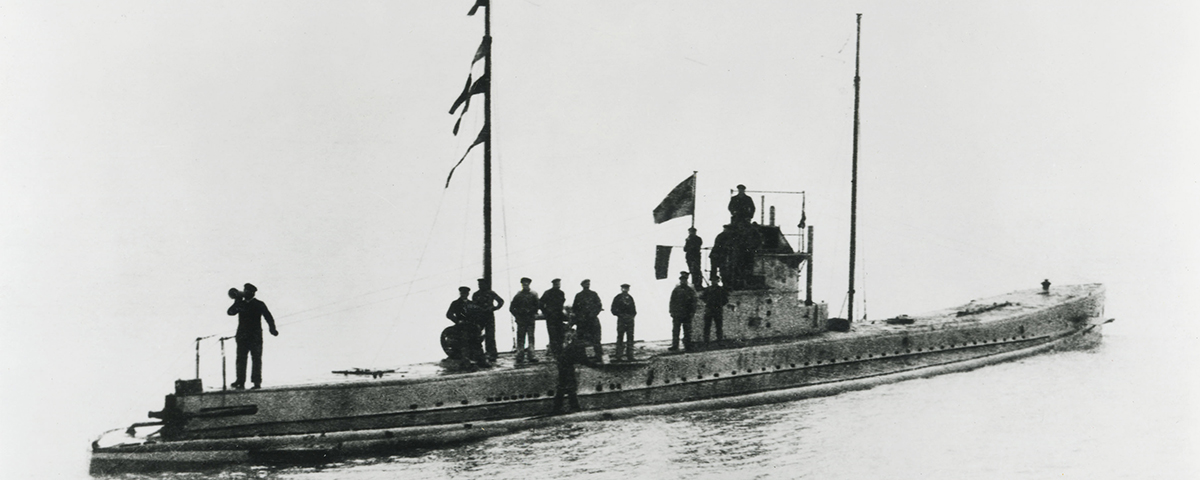

The last summer of the First World War saw Germany’s submarine war reach its peak, including attacks on shipping along the East Coast of the United States. The Kaiser’s navy had been deploying U-boats—from Unterseebooten, meaning “undersea vessels”—since hostilities began in 1914, but of those nearly 400 submersible warships only seven had the size and range to cross the Atlantic Ocean. These Type 151 subs, the Great War’s biggest, were 213 feet long with a beam of 29 feet, displaced more than 2,200 tons, and carried a crew of 56. Type 151s also carried 18 torpedoes, plus nearly 1,800 rounds for two 5.9-inch deck guns and another 764 rounds for two 3.5-inch deck guns operable while the boat was on the surface.

After the United States entered the war against Germany in April 1917, the U.S. Navy convened a special meeting in Washington, DC, to discuss an impending concern: “Defense against submarine attack in home waters.” Germany’s U-boats, the board warned, “may appear in American waters without warning,” perhaps occasioning “bombardment of coastal towns.” Defense against such attacks was the province of military bases that dotted the Eastern Seaboard. One was Chatham Naval Air Station, seven miles south of Orleans. Chatham Station had a force of four seaplanes whose crews patrolled the coastal waters. The airbase, which had a squadron of Curtiss R-9 bomber seaplanes with forward-facing “puller” engines mounted in their fuselages, recently had taken delivery of four newer Curtiss HS-IL seaplanes. Called “flying boats” because their undercarriages doubled as hulls, permitting water landings, HS-ILs mounted a V-12 engine centrally below the upper wing, just over the pilot and copilot, seated side by side. The engine powered a propeller configured to push the aircraft aloft and keep it there. An observer/bombardier perched at the nose to control the plane’s machine gun and, at Chatham, a single 230-lb. bomb, mounted under the lowerwing.

That morning, many Chatham pilots were aloft searching for a U.S. Navy dirigible that had been reported lost, but in the main these aviators were assigned to watch for German submarines that were ravaging shipping along the coast. In June 1918, U-151, taking up station off Virginia, harassed American shipping, in 24 hours sinking seven merchant schooners and sending alarms shivering up and down the Eastern Seaboard. “The waters within less than a hundred miles of the New Jersey coast are as full of peril as the waters of the North Sea or the English Channel,” declared the Philadelphia Public Ledger. A month later U-156 sowed the ocean south of Long Island, New York, with mines that on July 19, 1918, are believed to have sunk armored cruiser U.S.S. San Diego, killing six U.S. Navy sailors. Locally based warships and warplanes gave chase but the submarine escaped. Its commander, Captain Richard Feldt, set a course north.

Now it was two days later, and U-156 had surfaced three miles off Cape Cod to take aim at Perth Amboy and its barges. The crewman who had seen the original streaks now saw two more flash by, wide of the tug. This time the sailor cried out. As he yelled, Perth Amboy’s pilothouse exploded, struck by a 5.9-inch round from one of U-156’s deck guns. Tug helmsman John Bogovich crawled from the wreckage, his left arm and shoulder badly wounded. Tug captain James Tapley, who had been asleep, staggered topside and saw, in the distance, what looked like an enormous submarine firing round after round at his vessel. Most went astray, water fountaining into the sky. “I never saw a more glaring example of rotten marksmanship,” Tapley said later. However, given enough time and ammunition, the gunners were bound to score another hit. “All that we could do was to stand there and take what they sent us,” the tug captain added.

On shore, Coast Guard Surfman Moore alerted Station 40 keeper Captain Robert Pierce to “heavy guns firing on a tow of barges east northeast from the station.” In 30 years of lifesaving work, Pierce had never heard anything like this. He instinctively ordered his men to put a surfboat into the water, but as the situation revealed itself he wondered what he really could do. The beach was filling with onlookers, drawn by and terrified of the explosions at the besieged tug. “The concussion of the shells lifted the fog,” said Major Clifford Harris, the local State Guard commander. “I could see the flames coming up out of the forward hatch.” Station 40’s equipment included little of use against a U-boat. “That was quite ridiculous to our minds,” a surfman said. Captain Pierce knew the station’s 25-foot oar-powered surfboat had no chance against a submarine, but the alternative was to do nothing. He ordered his men to row to Perth Amboy, approximately three miles away, and sent a message to the naval air station at Chatham: “Submarine sighted. Tug and three barges being fired on, and one is sinking three miles off Coast Guard Station 40.” Pierce rushed to help launch the surfboat, boarding last and taking the tiller as he recalled the lifesaver’s creed: “You have to go, but you don’t have to come back.”

Seven miles from Orleans and not yet in receipt of Pierce’s message, Lieutenant Junior Grade Elijah Williams, executive officer at Chatham Naval Air Station, knew he was hearing naval gunfire. Most Chatham pilots were hunting that lost blimp, and whoever was supposed to be on base was in Provincetown for a Sunday morning baseball game against a minesweeper’s crew. But Lieutenant Williams wrangled a crew into a Curtiss HS-1L just before his signalman, taking down the alert from Station 40, confirmed what Williams feared: submarine attack. Within minutes Ensign Eric Lingard was aloft, bearing north. At the Curtiss’s top speed of 82 mph, Lingard and companions—copilot Ensign Edward Shields beside him, and bombardier Chief Special Mechanic Edward Howard at the nose—would be over Orleans in a trice.

Aboard Perth Amboy, captain Tapley and his crew braced for impact, but the submarine’s deck gunners were having trouble aiming. “The fire was very erratic, and the gunners seemed to be nervous,” Tapley construed.

The submariners fired as many as 20 rounds at the tug—“enough shots to sink the entire Lehigh Valley fleet,” Tapley said—but the pockmarked steel ship refused to sink. Still, Perth Amboy was essentially crippled. Flames licked what remained of the pilothouse.

Crewmen huddling helplessly at the tug’s stern decided to abandon ship. Tapley hoisted a white flag and the 16 refugees, boarding a lifeboat, started rowing the three miles or so to the beach.

The crew of U-156, content, pivoted from the disabled tug and began shelling the barges behind the tug, sinking three of four. Bargemen escaped in lifeboats with minor injuries and rowed for shore.

In their boat, Pierce and the surfmen had reached the Perth Amboy lifeboat, so near U-156 that concussions from the sub’s guns had blown off two lifesavers’ hats. “All have left the barges!” tugboat captain Tapley shouted. “My crew is here. For Christ’s sake, don’t go out where they are.”

Surfman Moore climbed onto the civilian lifeboat with his medical kit to treat the wounded. He began at the stern with the semiconscious Bogovich, whose shattered arm was bleeding badly. Moore tightened a tourniquet around the ravaged limb, hoping to stop or slow the blood loss. Taking an oar, he joined the tug’s occupants in rowing for shore amid splashes from rounds the U-boat gunners were loosing.

In his Curtiss bomber, Lingard was closing in. The engine roaring inches overhead had him trying to communicate with Shields by shout and gesture. Howard knew his job: when Lingard positioned the Curtiss over the sub, he let fly the plane’s Mark IV bomb. If the explosive device went off within 100 feet of a submarine, it would send the sub to the bottom. Below them, the sub’s gunners, engrossed in their shooting, were “blazing away complacently as if there was no air station with[in] a thousand miles,” Shields said later. Lingard kept the plane steady, 800 feet up. “They did not appear to see us until we were almost upon them,” Shields said. “As we nosed down toward them, there was a great deal of commotion and hustling around on deck. They then seemed in a Hell of a hurry to get away.”

Sighting “dead on the deck,” Howard pulled the release. Nothing happened. The bomb had hung up. Howard motioned to Lingard to circle for another attack. Lingard did, this time approaching the submarine at 400 feet, risking his plane and crew should an explosion envelop the Curtiss. Again, the bomb failed to release. Howard jumped back six feet from his nose seat and onto the plane’s lower wing. The sub was still in range. Lingard and Shields watched the mechanic nearly tumble from the sky. To their amazement, Howard regained his balance and, gripping a wing strut with one hand and the bomb with the other, he worked the Mark IV to fall in a perfect line with the submarine—except that the bomb that had hung up was also a dud. Lingard considered buzzing the sub to scatter the crewmen on deck but thought better of it when the German gunners began firing at his plane. To evade their rounds, Lingard went high and stayed there, figuring to track the submarine until more Navy planes arrived with functional bombs.

At Station 40, Tapley, Bogovich, and the rest of the men from Perth Amboy had beached, as had Pierce and his lifesavers. A doctor summoned to the strand thought Bogovich might lose his hand or arm but declared, “Whoever put this tourniquet on this man saved him from bleeding to death.” Captain Pierce focused on the abandoned barges, whose crews were en route to Nauset Beach, two miles north.

At Chatham Naval Air Station, everything that could have gone wrong had. At 11:04 a.m., station commander Captain Phillip Eaton, returning from the blimp search, landed to hear of the attack at Orleans. Eaton decided to go back up in an R-9 and try to sink the raider.

Lingard, who while evading enemy fire had been circling the sub, was happy to see his boss. “[It was] the prettiest sight I ever hoped to see,” he said. “Right through the smoke of the wreck, over the lifeboats and all, here came Captain Eaton’s plane, flying straight for the submarine, and flying low. He saw the high-angle gun flashing, too, but he came ahead.”

Eaton, flying solo, had to serve as his own bombardier. “As I bore down upon the submarine, it fired,” he said. “I zigzagged and dove as it fired again.” The sub’s deck crew was heading below. “They were getting under way and scrambling down the hatch when I flew over them and dropped my bomb.” His bomb, too, turned out to be a dud. Enraged, Eaton hurled a wrench and then the rest of the plane’s tools and toolbox at his targets, who thumbed their noses.

Fearing more enemy warplanes would be arriving, Captain Feldt ordered a dive and followed a southerly zigzag course out to sea. The assault on Orleans lasted 90 minutes, during which the enemy fired nearly 150 rounds in the only military attack on American soil during World War I.

Credited with sinking 35 vessels during the war, Captain Feldt died with the rest of U-156’s crew when the sub struck a mine in the North Sea in September 1918. Ensign Eric Lingard died of pneumonia in October 1918 after an engine failure forced his seaplane down in heavy weather. Perth Amboy helmsman John Bogovich made medical history. To mend his injuries, surgeons at Massachusetts General Hospital performed an early bone transplant to replace damaged tissue.