The rain has stopped, though steel-gray clouds hover above the World War II Memorial in Washington, D.C., where nine elderly men and one woman are escorted to their places of honor in front of a small crowd. On this 81st anniversary of the attack on Pearl Harbor, December 7, 2022, a wreath-laying ceremony pays tribute to these World War II veterans who fought across Europe and the Pacific.

Admiral Chris Grady, Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, gives the keynote, saying: “This memorial tells the story of the greatest generation that stood tall in the face of oppression, and we are here to honor those that sacrificed so much. And, of course, the price of freedom is always high, and it’s always paid in blood.”

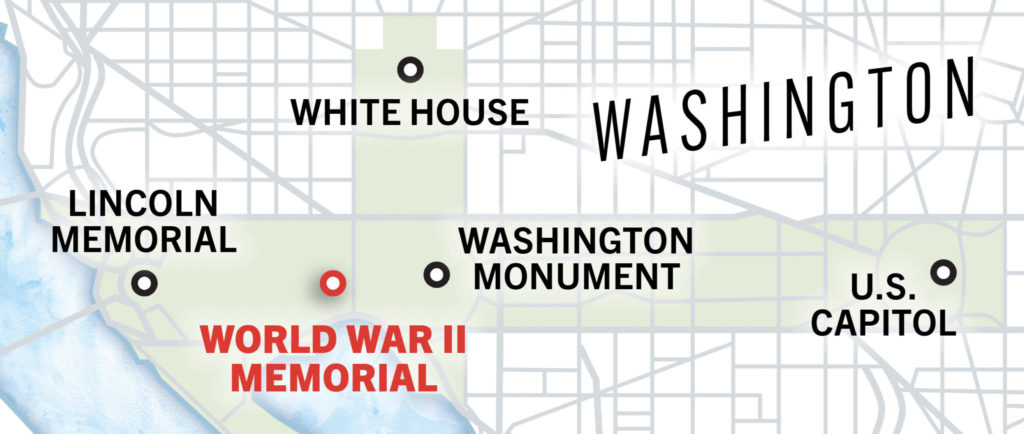

The setting couldn’t be more perfect. Dedicated in 2004, the World War II Memorial is a striking monument in a prominent place on the National Mall. Two impressive rows of 17-foot pillars and a pair of triumphal arches surround a fountain-bedecked plaza, creating an impression of power and might. Quotes from Presidents Franklin D. Roosevelt and Harry S. Truman and many commanding officers of America’s wartime military adorn the memorial’s walls.

But it’s more than just a heroic-looking monument. The World War II Memorial contains layers of meaning, and by understanding that symbolism, the presence of the honored veterans—indeed, the presence of this memorial on the National Mall—becomes even more poignant.

“It’s a triumphant memorial,” Ranger Nate Adams tells me as he guides me around the monument. “You’re honoring the dead here, for sure. But this memorial is talking about victory, unity, and sacrifice.”

We walk along the memorial’s ceremonial entrance, where 24 bronze bas-reliefs sculpted by Ray Kaskey depict both home-front and battle scenes in chronological order—12 on the north side representing the Atlantic Theater, and 12 on the south portraying the Pacific Theater. The panels show the complete transformation of American society as it mobilized military, agricultural, industrial, and human resources to fight for democracy—and how less represented people were instrumental in achieving victory. In one panel you’ll find Rosie the Riveter, for example, the cultural icon typifying the women who worked in factories and shipyards. Others show African Americans, in the throes of segregation, who answered the call to fight and to help on the home front.

As Nate leads me along the northern row of pillars etched with the names of states and territories, my eye catches the Philippines, where my mother grew up and was imprisoned by the Japanese during World War II. “The elements of sacrifice on the pillars are important,” Nate says. “There are two wreaths on each pillar, one on front and one on back.” They are oak and wheat, representing industry and agriculture. “So not only did the states and territories give up their sons and daughters; they also gave up their hard work and resources.” A rectangular hole cut out of the center of each pillar represents those who didn’t come home, while twisted bronze roping at the pillars’ base connects each state and territory. “What can be more indicative of unity than a rope binding it all together?” Nate says.

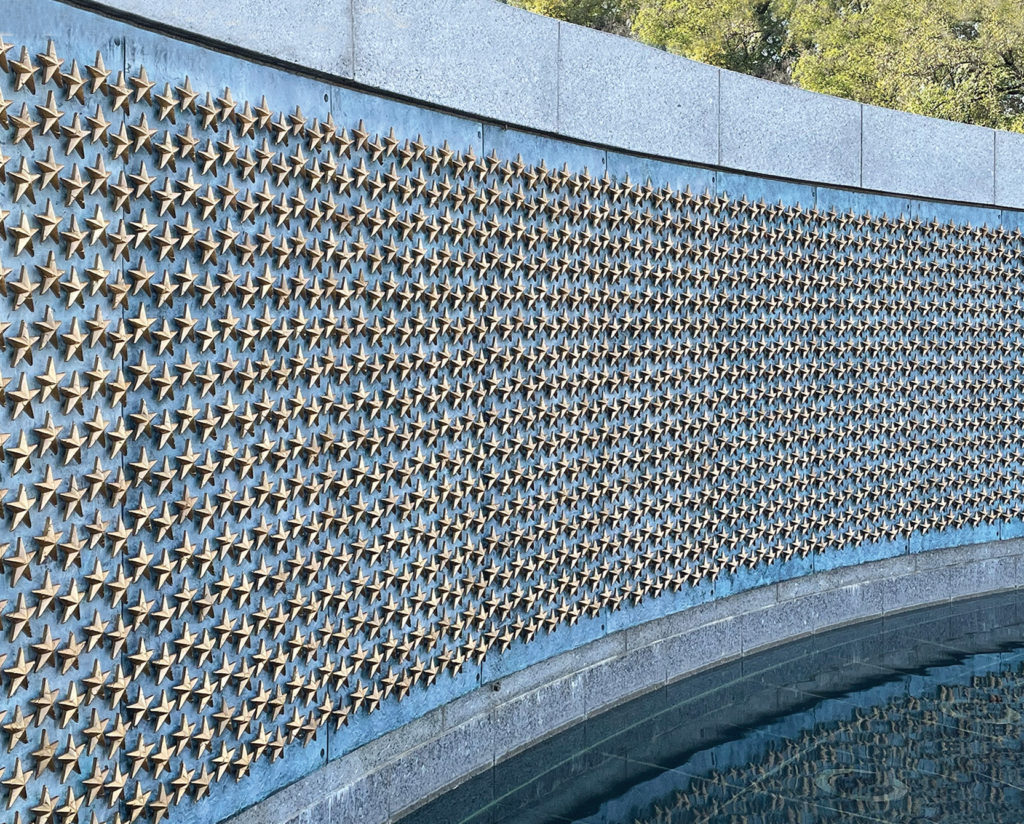

I have to ask: “Are the pillars arranged in the order the states came into the Union?” That, apparently, is the most popular question visitors ask rangers. Nate’s response intrigues me. “The monument honors the dead,” he says, pointing to a field of gold stars at the memorial’s western side, commemorating those who did not return, called the Freedom Wall. “That’s the head of the table, and they’re seated at the place of honor. Protocol says that you seat your most honored guests closest to the right, closest to the left, back and forth.” In this case, the most honored guests are in order of state ratification of the Constitution and admittance to the Union as a state or territory—Delaware is first, on the right, then Pennsylvania, on the left, and so on, all the way through the territories and District of Columbia.

As we make our way toward the Freedom Wall, we walk through the Atlantic victory pavilion, one of two small open-air vaults standing opposite one another across Memorial Plaza, representing the two theaters of war on opposite sides of the world.

Standing inside, my eyes are drawn to the sculptural canopy above our heads, officially called a baldacchino. Four bald eagles, with wing spans of 11 feet, carry garlands in their beaks, which in turn support a laurel victory wreath. “The artist, Ray Kaskey, said, ‘Let’s do something different,’” Nate says. “He had seen something in a church in Rome, a circle with angels. But he put eagles. What’s more American than the bald eagle?” Beneath our feet, an enlarged bronze medallion depicts the World War II Victory Medal, with the goddess Nike or a figure of Liberation (it’s debated which) looking into the dawn of a new day. The medal was awarded to all members of the military who served in the war.

Water is a prominent feature of the World War II Memorial—the architect, Friedrich St. Florian, placed fountains and ponds throughout. Rainbow Pool, in the center of the main plaza, existed before the memorial was built. Two fountains rise from the pool in spectacular watery flows, accentuating the victories in the Pacific and Europe. Some say they also represent the European fountains American soldiers joyfully played in at the war’s end. As we near the Freedom Wall, we stroll past more cascading waters splashing loudly over a berm supporting the memorial’s western side. “You hear the noise of the water,” Nate says, adding “then, as you approach the stars, it’s quieter. It makes this area seem more somber.”

The Freedom Wall, the memorial’s focal point, rises above a placid pond. Across its dark façade are 4,048 gold stars, each one representing approximately 100 American service members who lost their lives during the war. In front of the ensemble, words on a stone marker proclaim: “Here We Mark the Price of Freedom.” As Admiral Grady said in his speech, “It is proof that freedom is worth dying for, it is proof that no matter the cost, brave men and women will answer this nation’s call.”

Nate mentions something else. “This is a place where hard stories are shared,” he says. “I remember when a veteran was here with his son. The son told me, ‘I found some medals in a case, and one was a silver star.’ I looked at him and said, ‘They don’t give you a silver star for sitting behind a desk.’ That man had been in a very dangerous situation and did something incredibly brave. The father had never shared that story.” Stories like that are revealed time and time again in this sacred space, he says.

Not everything about the memorial is sobering. Nate reminds me that so many soldiers were very young men, 18 and 19 years old. That’s why, tucked away in unassuming nooks, are two “Kilroy was here” etchings—Kilroy, of course, is the famous chalk-and-pencil sketch of a big-nosed man peering over a wall that popped up everywhere during the war as a morale booster. The National Park Service doesn’t tell people where they are. You have to find them yourself. (Hint: they’re outside the main memorial space.)

I then meet Dan Arant, a National Park volunteer who provides additional insights into the memorial’s symbolism. He leads me to the Announcement Stone, a block of granite at the monument’s ceremonial entrance on 17th Street. In the years before its dedication, the memorial was a controversial project. “So many people were against it,” Dan says. “There were public hearings and lawsuits, all against it.” It took 17 years before Congress voted its approval.

Part of the issue was the memorial’s central location on the National Mall; some people feared it would break up the sweeping vista between the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial. “This Announcement Stone explains why the memorial is where it is,” he says. The quotation engraved on it starts: “Here in the presence of Washington and Lincoln…” And this is perhaps the memorial’s most powerful symbolism—its presence looks to the nation’s forefathers who established democracy, and spotlights the importance of American generations later who sacrificed so much to preserve it.

In this setting, the veterans at the end of the Pearl Harbor ceremony are ushered to the Freedom Wall, where they lay wreaths on behalf of each military branch. Guests shake their hands and thank them for their service against the backdrop of gold stars shining brightly in their place of honor.