As the war effort ramped up to full speed, U.S. Army planners turned 2,000 acres of quiet New York farmland into the busiest military embarkation camp in the world.

IN THE DARKEST HOURS of many nights from April 1943 to May 1945, people living on the outskirts of Orangeburg, New York, awoke to the heavy footfalls of soldiers on their final march on American soil. Division by division—from the 6th Armored to the 101st Airborne—nearly 1.3 million uniformed men and women filed from the Camp Shanks staging area to railcars and ferries that would transport them 30 miles south to ocean liners waiting at the mouth of the Hudson River.

The soldiers, among them three-quarters of the Americans who would invade France on D-Day, marched by clapboard buildings where the army had ensured their equipment and personal affairs were in order. They passed stages where the likes of Ethel Merman and Judy Garland had offered them Broadway diversions and rainbow daydreams during their fleeting stay. Those departing by ferry skirted a silk mill in the village of Piermont that spent its days churning out ribbons for medals to be pinned to the chests of men who had preceded them across the Atlantic.

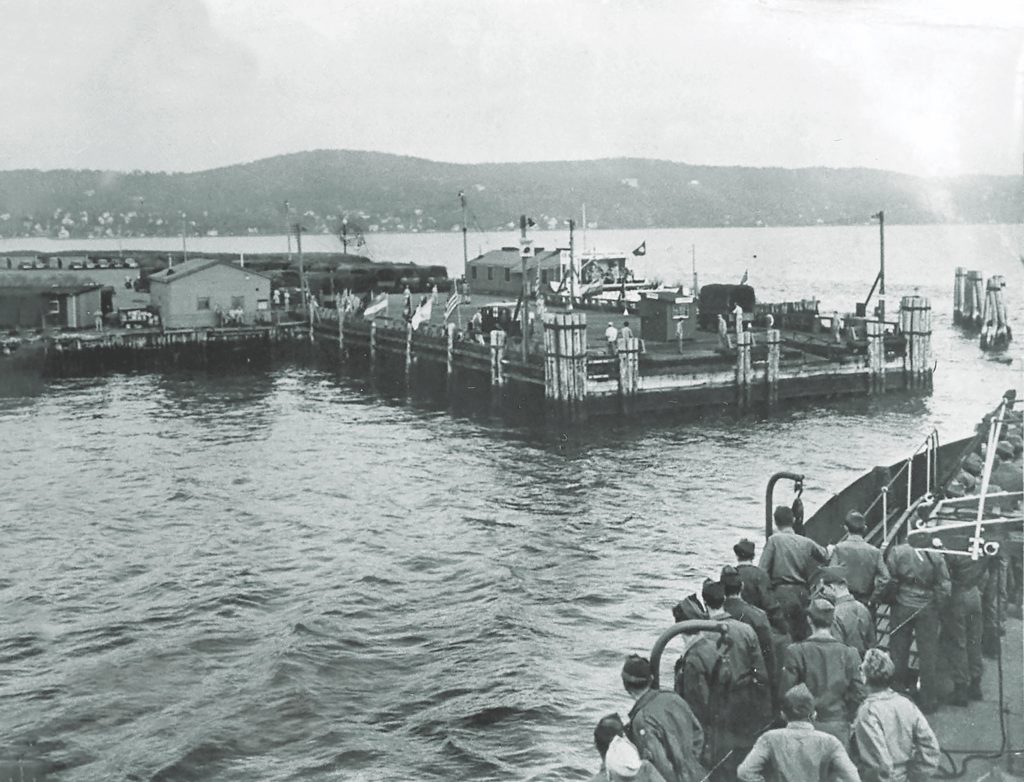

A mile-long wooden pier took the soldiers through head-high wetland reeds to a ferry slip in the deepest part of the Hudson. Neatly dressed Red Cross volunteers offered donuts and paper cups of steaming coffee, while local boys who had sneaked out to check muskrat traps hid in the shadows and watched boots that would storm Normandy and defend Bastogne stamp out final cigarettes. When their commanding officers issued the order, each soldier hefted a bulging duffle bag, climbed up the gangplank, and set off to war.

IT WAS AN EARLY September afternoon in 1942 when Major Drew Eberson of the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers motored north from New Jersey into New York amid the first hints of fall colors on a new assignment. Before departing the United States for either theater of its evolving war, every soldier underwent final inspection and processing at one of several army ports located in coastal cities like Seattle, San Francisco, New Orleans, and Hampton Roads, Virginia. The army tapped its New York Port of Embarkation, consisting of Brooklyn’s Fort Hamilton and New Jersey’s Camp Kilmer, as the primary departure point for troops bound for Europe and North Africa. Some 150,000 U.S. soldiers had already crossed the Atlantic. Expecting to send hundreds of thousands more in the coming months, the army dispatched Eberson to scout a location for a new staging area that would double the capacity of the New York Port of Embarkation, making it the largest in the world.

Twenty miles north of Manhattan, Eberson pulled to the side of Western Highway to survey the hamlet of Orangeburg, population 500. Established by Dutch farmers through trade with the Tappan band of Algonquin Indians in 1686, the area was dominated by rolling fields of cabbage, tomatoes, and corn. Orangeburg checked every one of Eberson’s boxes. The farmland and sparse population meant minimal demolition and displacements. The Erie Railroad and the West Shore line of the New York Central crossed tracks here and could support troop movements. With a little dredging and construction of a pier, the Hudson River, fewer than two miles east, could provide ferry access to New York Harbor.

On September 25, Eberson gathered 130-some nervous local landowners in a school auditorium to break the news: under the authority of the War Powers Act, the Army Service Forces would be purchasing their properties above market price. The acquired parcels totaled 1,365 acres. The army would lease an additional 675 acres of state land to round out what would be called Camp Shanks in honor of Major General David C. Shanks, who directed the New York Port of Embarkation during World War I. The Corps of Engineers’ plan would create a base a mile wide—from Western Highway to Rockland State Hospital, a psychiatric facility that would lend the army medical wards—and two-and-a-half long, stretching into the hamlets of Blauvelt to the north and Tappan to the south. Residents had two weeks to vacate.

IT WOULD COST just shy of $45 million to transform Orangeburg into a camp that could accommodate a staff of 5,500 permanent military personnel and some 40,000 transient soldiers at any given time. The army contracted Cauldwell-Wingate Company to put up the post’s 2,500 buildings and Poirier McLane Corporation to develop the area’s first sewer system and other supporting infrastructure. With the army expecting to process outbound troops through Shanks by spring of 1943, the companies put more than 17,000 local draftsmen, carpenters, mechanics, and general laborers on the job. One of the first on payroll was Leonard Hunt, a salesman from nearby Nyack who, on his first day in late September, bulldozed row after row of cabbages ripe for harvest.

Construction crews persevered through an unusually cold winter—temperatures dropped to a record -26 degrees—and the first staff members reported for duty at the half-finished camp on January 4, 1943. The army took great care to protect information about troop movements. Although locals were well aware of Camp Shanks, its name and purpose would be concealed from outside media. One of the first acts of the camp’s commanding officer, Colonel Kenna G. Eastham, was to establish a biweekly newspaper that would meet the information and entertainment needs of both permanent and passing soldiers. The Palisades was staffed by a team of experienced prewar news editors and reporters, along with cartoonist Bill Wenzel, whose voluptuous female characters earned much of the credit for the four-page tabloid’s readership and launched his three-decade career as a prolific pinup artist.

While the military staff settled in, the army advertised for some 1,500 civilian workers to augment the motor pool and run post exchanges for about $250 a month. Eighteen-year-old Ruth Beard Stoughton of Tappan gladly quit her split-shift job as an operator at Bell Telephone to hock 3-cent candy bars at the PXs, where she enjoyed more than her share of Reese’s Peanut Butter Cups. Fully staffed and with construction nearly complete, Camp Shanks welcomed its first deploying troops on April 17.

WHEN ARMY DIVISIONS training in camps around the country received orders to embark from New York for Europe or North Africa, their entire complement loaded in train cars bound for Camp Shanks or Camp Kilmer in New Jersey. Orders were secret, and troops seldom knew which camp they were headed to. Stoughton’s brother, Paul Russell Beard, had an advantage. A field artillery forward observer with the Third Army, the staff sergeant fell asleep shortly after his unit departed its Maryland training center. He awoke just in time to spot Skinner’s Bar on Oak Tree Road in Tappan, a few blocks from his family’s Italianate home, and knew he was destined for Shanks.

Troops rarely stayed in Orangeburg for more than a week. The Camp Shanks experience began with quick medical and dental exams, a review of vaccination records, and administration of missing shots. Soldiers tested their gas masks in one of three tear gas chambers and practiced abandon–ship drills—climbing down vertical cargo nets into simulated rowboats to prepare them for potential trouble during the Atlantic crossing. The latter activity made a lasting impression on Tula Civeta LaValley, whose Women’s Army Corps (WAC) unit passed through Shanks in the spring of 1943. “If I ever had to do that [at sea], I’m sure I would have stayed on the ship!” she reflected years later.

Shoulder patches and other unit-identifying insignia were removed from uniforms in case the transports should fall into enemy hands. There were lectures on mail censorship, insurance benefits, and legal matters. During one particularly somber talk, an instructor lightened the mood by calling Army Air Forces sergeant Ralph Scott from the audience to sing “When Irish Eyes Are Smiling” to a young woman who was employed in an adjacent office. “I could see the grins on my men who were enjoying my embarrassment, and all I wanted about then was to be someplace else,” Scott recalled.

Each soldier would depart equipped for battle. Quartermasters ensured every infantryman had a fully functioning M1 rifle with bayonet, as well as a helmet, cartridge belt, and field pack with required contents—raincoat, shelter-half tent and poles, canteen, toiletries, mess kit, first aid pack, entrenching tool, and more. Any item found wanting was repaired or replaced before the soldier shipped out. In Shanks’s busiest month, October 1944, the Quartermaster Corps issued 646,000 pieces of new equipment.

WHILE MOST UNITS were cleared for deployment just two days after arriving in camp, they typically had to wait another four to five days for their transatlantic voyage. As a staging area, Shanks lacked the training facilities the army traditionally used to keep soldiers busy, so top brass sought other means to prevent idle soldiers from brooding over the perils awaiting them across the pond.

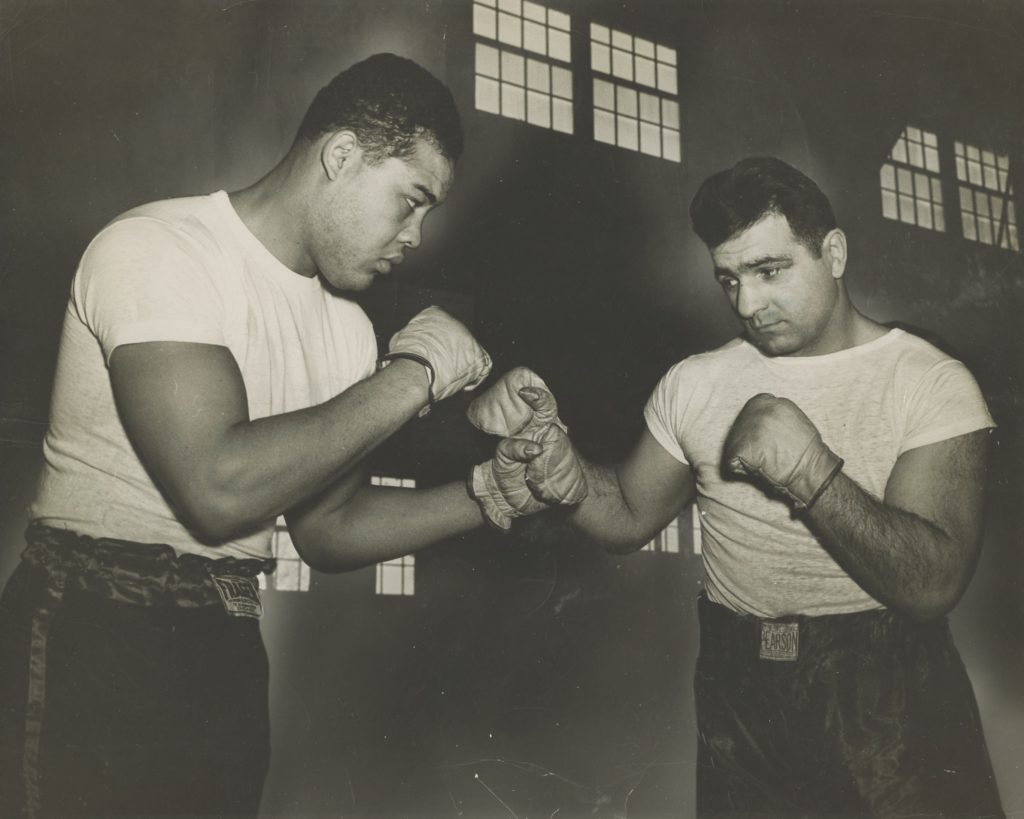

The war department had created Special Services, a recreation and entertainment unit, in July 1940 to maintain troop morale. No base had a finer office than Camp Shanks. Permanently assigned musicians, composers, and comedians staged nightly performances, while boxing greats like reigning world heavyweight titleholder Sergeant Joe Louis refereed amateur matches and fought exhibition rounds. Drawing on talent within Shanks’s permanent staff, the office organized a 28-piece orchestra and fielded a baseball team that held the Chicago Cubs to a 5-2 victory and a basketball squad that took on the Harlem Globetrotters. “They beat the hell out of us,” remembered Herbert Walden of Shanks’s 22nd Medical Detachment. In the camp’s first six months, 44,000 troops swam in the pool and 122,000 enjoyed prerelease films in one of the six movie theaters.

Special Services had the dual job of attracting visiting talent to Camp Shanks. Vaudeville, Broadway, and Hollywood stars jumped at the chance to entertain outgoing troops on the camp’s four main stages, including the “Shanksmobile,” a wheeled platform modeled after a Mississippi showboat. Soldiers roared at the antics of Jimmy Durante and Mickey Rooney and cheered for queens of screen and stage like Myrna Loy and Helen Hayes.

In 1944, Camp Shanks was the proving ground for a playful musical satire of army life meant to boost morale across the globe. Hundreds of Shanks staffers responded to the casting call for About Face, whose authors included Army Air Forces private Frank Loesser, the Broadway composer serving in Special Services who would pen Guys and Dolls after the war.

Designed for easy production at overseas bases, the script featured short comedic sketches and catchy tunes written in registers the average untrained G.I. voice could manage. Accompaniment could be as sparse as a piano, or as robust as a full orchestra. Suggested props and costumes were simple and easily sourced; a soldier could become Abraham Lincoln with just a bathrobe, a string tie, and a crepe paper-and-tape beard.

About Face, which opened in the camp’s filled-to-capacity Victory Hall on May 26, 1944, was an instant hit. The audience howled at numbers like “Gee, but It’s Great to Be in the Army,” which facetiously celebrated soldiers’ newfound housekeeping and laundry skills with lines like: “When I get back to civilian life, I’m gonna make someone a hell of a wife.”

In April 1945, a pinstriped Frank Sinatra chatted up members of Shanks’s two WAC detachments, then broadcast a live radio show before an audience of men about to ship out as replacements. “The GIs reacted to Frankie as though they were wearing bobby-sox instead of battle-boots,” The Palisades reported.

SOLDIERS WHO TIRED of the base amenities could venture off with a 12-hour pass. The surrounding communities welcomed them at four USO clubs. Each offered complimentary food and the friendship of young civilian hostesses, who were recommended by clergymen and trained in the proper wardrobe and etiquette for providing G-rated company to soldiers on the brink of deployment.

In Tappan, local volunteers swept the cobwebs out of the Dutch Reformed Church’s old manse barn to create a dance floor that could hold 600 people. On any given day, soldiers could try Ping-Pong, finger-painting, or cigarette bingo. Guides offered historical walking tours of the neighborhood where George Washington had briefly camped the Continental Army in 1780.

The Camp Shanks-area USOs were noted for going above and beyond. On March 3, 1945, the Nyack club bused 150 Japanese American women from New York to join a dessert-and-dance party for soldiers deploying as replacements for the all–Japanese American 100th Infantry Battalion, whose members would be awarded eight Medals of Honor for their service in Europe.

Outside the USOs, soldiers filled the barstools of many local watering holes. Herb Walden recalled that Bill Larkin’s tavern, just off base from the hospital, was a particular favorite. “The big parking lot had more fights in it than the whole history of Madison Square Garden,” he said.

For 45 cents, soldiers could hop a bus to the Big Apple for a taste of the nightclub scene. The 502nd Parachute Infantry Regiment preferred the tiki-themed Hurricane Club. First Lieutenant Wallace Strobel’s only vivid memory of his short stay at Camp Shanks was the night a friend arranged for him and three G.I. buddies to see a Hurricane show called Early to Bed, then paint Park Avenue red with four of the act’s female stars.

CITY LIGHTS AND charming ladies provided temporary distractions for the waiting soldier, but little could numb the nerves once a unit was placed on alert status with fewer than 12 hours to departure.

Restricted to base, soldiers chalked passenger list numbers on their helmets and duffle bags and often reclined on their wool-blanketed bunks to draft one last stateside letter. Many sent any remaining U.S. currency off to their families—one Shanks postal clerk recollected writing upward of 600 money orders a day—or made final PX purchases. Ruth Stoughton was filling soda orders one late December afternoon when she noticed a soldier staring into the distance as he leaned against a jukebox playing “White Christmas.” “He looked so sad and lonely,” she remembered. “Every time I hear that song I still think of that guy.”

Troops moved out quickly and secretly. During Paul Beard’s brief time at Camp Shanks, he made a nightly habit of sneaking out the gate, where his sister was waiting to give him a lift to the family home on Oak Tree Road. “I went up one night to get him and he was gone,” Stoughton recalled.

To protect against possible enemy air observation, soldiers typically left Camp Shanks in the dark. Divisions would muster an hour before departure and shed their helmets for a chaplain’s final blessing. While some left by ferry, the majority departed by train from the southeast corner of the post. The march took them right past the WAC barracks. Women would often pull overcoats over their pajamas and gather roadside to wave goodbye, the occasional low wolf whistle punctuating the steady beat of combat boots on pavement. An entire battalion could be loaded on a train and gone in just four minutes. On Camp Shanks’s busiest day in October 1944, 27,626 men—nearly two whole divisions—departed its gates.

In the upper reaches of New York Harbor, soldiers loaded onto transatlantic transports. For some, these were the Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth, ocean liners that could carry upward of 16,000 passengers and outpace German U-boats. Arriving in England or Scotland, each unit would transfer to a staging area and await the start of its war.

IN JANUARY 1945, traffic began flowing the other direction. Thirteen hundred American soldiers were pulled off the front lines for a month-long furlough and arrived at Camp Shanks for in-processing. With the tide of the war turning, civilian media were welcomed through the gates for the first time to share the story of battle-hardened men guzzling milk, lingering under hot showers, and making teary-eyed phone calls home.

Outbound troop shipments dropped dramatically in March 1945 and had stopped altogether by Germany’s surrender on May 7. The Shanks Quartermaster Corps, which had supervised the departure of nearly 1.3 million U.S. soldiers, celebrated V-E Day in the basement of its headquarters. “Rank was tossed out the window and much fluid was tossed down the hatch,” according to an informal unit history.

Returning soldiers flooded into Camp Shanks. Within 24 hours of arrival, they were on trains to reception stations near their hometowns. This included 45,000 men who shipped directly from Europe to the Piermont Pier. Marching up the dock, they were greeted by masses of cheering locals, many holding signs asking for any news of their loved ones.

The SS Marine Fox delivered the 10th Mountain Division’s 85th Infantry Regiment on sunny August 11, 1945, two days after the second atomic bomb dropped on Nagasaki. The camp was abuzz with hopes of a war-ending Japanese surrender. The men celebrated with a steak dinner and a post-amphitheater show in which actress Betty Grable, who had starred in many soldiers’ pinup dreams, welcomed them home in person.

When the 38th Field Artillery arrived at Camp Shanks, the Battery C clerk opened his duffle bag to reveal unconventional luggage—a 12-year-old Polish boy named Joseph Peremba. The orphan was laboring on a farm in Germany when Battery C made him an honorary ammunition carrier. It took the Supreme Court and Congress years to straighten out Peremba’s legal status, but he was eventually adopted into the clerk’s Oklahoma family.

CAMP SHANKS’S final assignment was staging nearly 290,000 German and Italian prisoners of war returning home. The War Department planned to convert the camp into a national cemetery upon decommissioning in July 1946, but Columbia University proposed an alternative.

To alleviate an acute housing shortage, barracks were repurposed into 1,100 apartment units that veterans enrolled in New York colleges could rent for as little as $29 a month. Most Shanks Village families lived on a meager $120 monthly stipend. Resourceful residents developed grocery cooperatives, babysitting pools, and other communal approaches to living that drew Life magazine, curious politicians, and anthropologist Margaret Mead to visit the village before its 1956 closure.

Many veterans of Camp Shanks and Shanks Village settled permanently in the Orangeburg area, aiding its transformation into a New York City bedroom community. Shanks buildings were torn down or sold off, and in 1958 the new Palisades Interstate Parkway bisected the former grounds, offering commuters a quick route south to the city. Today the only surviving traces of the staging area dubbed “Last Stop USA” are a few officers’ homes, a flagpole, and the pier that saw thousands off to war. ✯

This article was published in the August 2020 issue of World War II.