Tired of being on the run, the Wild Bunch leader considered a number of options before deciding it was best to leave the country.

Before fleeing to Argentina with the Sundance Kid and Etta Place to start a new life early in the 20th century, did Butch Cassidy offer to give himself up to the authorities and seek amnesty? The evidence that he did is persuasive. Did he also nearly make a deal with the Union Pacific Railroad to give up robbing its trains if he was offered a job as one of the railroad’s express guards? That tale is a little shaky.

There are two similar but slightly different versions of the surrender offer. One can be found in Charles Kelly’s popular The Outlaw Trail: A History of Butch Cassidy and His Wild Bunch, first published in 1938 and updated by Kelly in 1959. As Kelly tells the story, one day in the fall of 1899, a “stocky well-dressed man” entered the office of Orlando W. Powers, a prominent Salt Lake City attorney. The man asked Powers if what he was about to tell him would be held in strict confidence. When the attorney assured him that it would, the man said, “My name is George LeRoy Parker, better known as Butch Cassidy,” and added that he wanted to “quit this outlaw business and go straight.” After reciting the recent fate of several members of his gang, Cassidy said: “Sooner or later it’ll be my turn. I figured it was a good time to quit before I got in any deeper.”

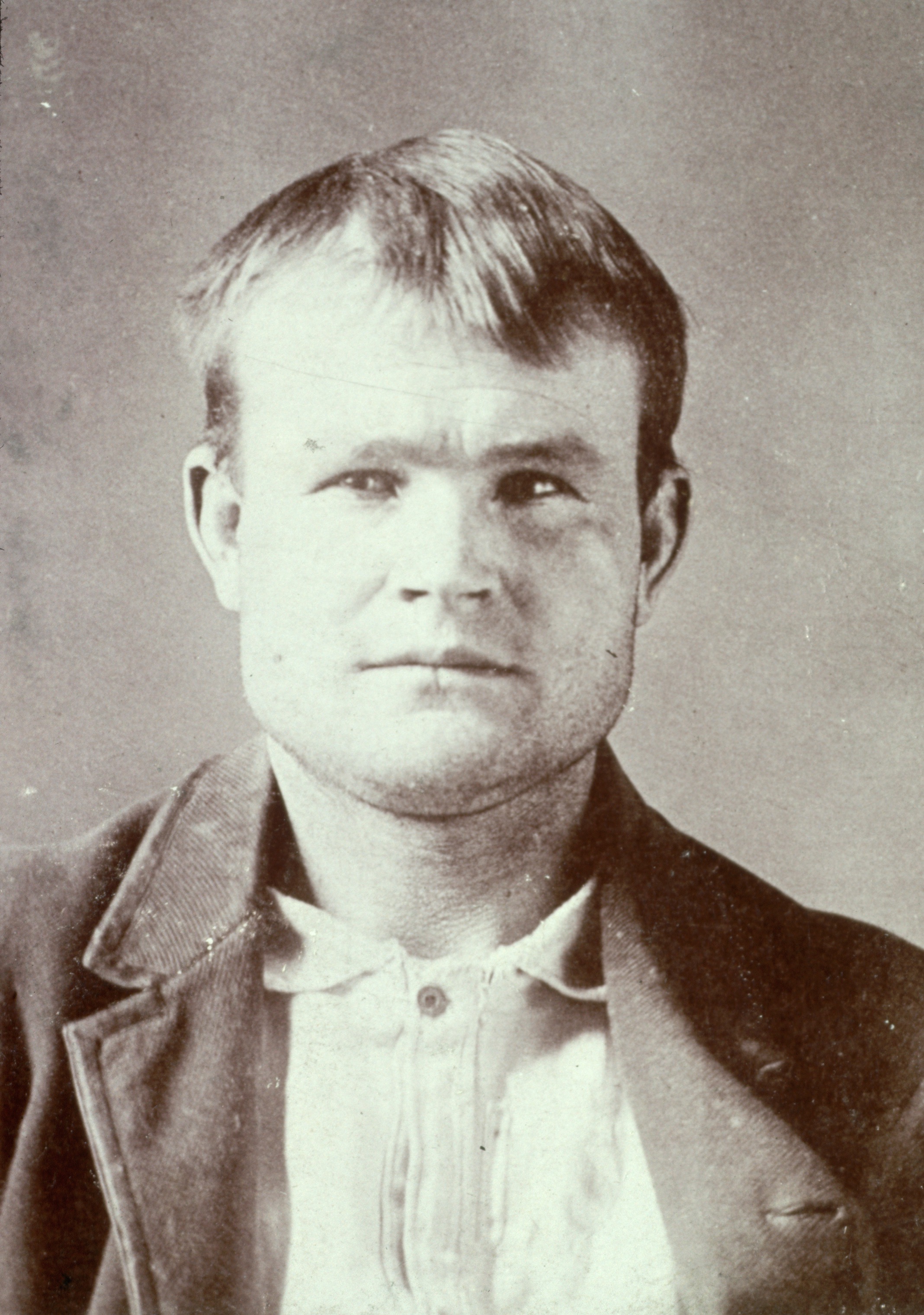

It’s no surprise that Butch was ready to call it quits. He was not your typical outlaw. In fact, he was not unlike the character portrayed by Paul Newman in the 1969 movie Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid. (For once Hollywood might have gotten something right.) Butch could be amusing and disconcerting, and at times self-deprecating—traits that would seem out of place for a turn-of-the-century criminal.

Butch was hardly cut out to be a fugitive. He enjoyed the friendship of law-abiding citizens. Even while wanted by the law, he spent much of his time peacefully in communities where he not only seemed to get along well with his neighbors but also tended to develop close relationships— Wyoming’s Dubois, Lander and Star Valley; the Brown’s Park area of Colorado; and in later years, Cholila, Argentina.

Prior to walking into Orlando Powers’ office that day in 1899, Butch and the attorney had never met. But they had previously done business. In 1896 Butch’s friend Matt Warner and two others, Dave Wall and E.B. Coleman, had been arrested for the murder of two men in a dispute over a mining claim near Vernal, Utah. Warner and Wall were without funds, and Butch made arrangements through his Wyoming lawyer, Douglas Preston, to hire Powers and his partner, D.N. Straupp, to defend them. To obtain the money for the lawyers’ fee, Butch robbed a bank in Montpelier, Idaho. (Powers later denied this, claiming he was paid by relatives of E.B. Coleman.)

At the meeting in Powers’ office, the lawyer patiently listened to Butch Cassidy insist that he was not as bad as people painted him, that he had never killed a man in his life, and that he never robbed individuals, only banks and railroads. When Butch was through, Powers asked, “What do you want me to do?”

“Just this,” Butch answered. “You’re the best lawyer in Utah. You know who’s who and what’s what. You’ve got a lot of influence. I thought maybe you could fix things with the governor to give me a pardon or something so I wouldn’t be bothered if I settle down and promise to go straight. I’ll give you my word on it. Is there any way it could be fixed?”

According to Kelly, the lawyer’s reply was not encouraging. He told Butch that he would like to help him, but there were obstacles. For one thing, he said, the governor of Utah, Heber M. Wells, could only issue a pardon for crimes committed in Utah, and so far Cassidy had not been convicted of any crimes there. He was suspected of the 1897 robbery of the Pleasant Valley Coal Company payroll at Castle Gate, Utah, and if he pled guilty to that crime, or was tried and convicted for it, a pardon by the governor would be effective in Utah, but it would offer no protection against warrants for crimes Butch might have committed in other states. “No, Cassidy,” Powers said, “I’m afraid you’ve gone too far to turn back now, at least to settle in any of the Western states. The best advice I can offer you is to leave the country and make a new start someplace where you are not known.”

Butch thanked him for the advice and said: “You know the law, and I guess you’re right; but I’m sorry it can’t be fixed some way. You’ll never know what it means to be forever on the dodge.”

There is another version of Butch Cassidy’s meeting with Powers—in A.F.C. Greene’s “Butch” Cassidy in Fremont County, a monograph that appeared around 1940 and was reproduced by Jim Dullenty in The Butch Cassidy Collection (Hamilton, Mont., Rocky Mountain Press, 1986). As in Kelly’s version, the scene is the attorney’s office in Salt Lake City. Greene was more descriptive. He says Powers’ stenographer ushered a man into the office who was “somewhere in his forties, although some of the lines on his big face might have come from hard living in the open, or from whisky; his hair, which had been flaxen, was shot with grey; a rough looking customer, dressed in overalls and a blue denim jumper.”

According to Greene, this conversation took place:

Cassidy: Is what I say to you to go as a client consulting his lawyer from now on?

Powers: You mean, a privileged communication?

Cassidy: That’s it.

Powers: All right then.

Cassidy: I’m Butch Cassidy.

Powers: Well, what can I do for you?

Cassidy: I’ll tell you. There’s a heap of charges out against me and considerable money offered for me in rewards. I’m getting sick of hiding out; always on the run and never able to stay long in one place. Now, when it comes to facts, I’ve kept close track of things and I know there ain’t a man left in the country who can go on the stand and identify me for any crime. All of them have either died or gone away. I’ve been thinking. Why can’t I go and just give myself up and stand trial on one of those old charges?

Powers: No use. You’ve robbed too many big corporations in your time. I do not doubt what you say, but if you were ever to go on trial you can depend on it, some one of those companies would bring someone to the stand who’d swear against you. No, you’ll have to keep on the run, I’m afraid.

In substance, the two versions vary little, and had either author paraphrased the conversation, the slight differences would have likely gone unnoticed. However, both Kelly and Greene chose to report the conversation verbatim. Even then, the most notable difference concerns how Butch Cassidy was dressed. Kelly says “well-dressed,” which suggests city clothes, while Greene says “overalls and a blue denim jumper,” as if Cassidy had recently come off the trail. Granted, this is a minor inconsistency, but it does raise one’s curiosity.

Something else in Kelly’s version is bothersome. He says Butch introduced himself to Powers as “George” LeRoy Parker. Cassidy’s real name was Robert LeRoy Parker, a fact later verified by his family and by church records. It’s true that during his outlaw career Butch did use the name George Cassidy, and throughout his book Charles Kelly mistakenly refers to him as George. However, if Butch chose to bare his soul to Powers and seek his help, would he not have used his real name? Again, this minor discrepancy would mean little if it were not that Kelly was purporting to provide a verbatim account of the meeting.

Partly because of this slip, I chose Greene’s version over Kelly’s for my book on Cassidy, reducing Kelly’s account to an endnote reference. Another reason I favored Greene is that he had been a contemporary of Cassidy’s and might have even known him personally. What’s more, it’s rumored that Greene was related by marriage to the John Simpson family, who were Butch’s neighbors and close friends when he had his ranch near Dubois, Wyo.

As minor as these discrepancies were, I couldn’t let them alone, so recently I dug a little deeper into the matter, hoping to find the source (or sources) of the two accounts. Thanks to a tip from Wild Bunch writers Dan Buck and Anne Meadows, it did not take long to learn where Greene’s version came from. He took it word for word from Frederick R. Bechdolt’s 1924 book Tales of the Old Timers, a source that I had failed to track down when I was writing my biography of Cassidy.

I was aware of the Bechdolt book at the time, but it had been out of print for years, and after a brief search for a copy I gave up looking. Frankly, I was put off by the title, thinking it was just one of those many potboilers on the Old West cranked out in the 1920s. After all, Bechdolt was primarily a novelist and short-story writer whose stories occasionally had been adapted by Hollywood for early two-reel Westerns.

I had underestimated Bechdolt. It seems he also turned out some decent frontier history.

So, if Bechdolt’s book was the first published account of the story of Butch’s offer to surrender, what was his source? Bechdolt’s Tales of the Old Timers was mostly about southwestern frontier characters. He devoted only one chapter to Butch Cassidy. Like Charles Kelly and A.F.C. Greene, he did not include footnotes or endnotes, but he did provide a single page of “Acknowledgments.” Among the names mentioned there with a connection to Cassidy were W.A. Richards (Wyoming governor during part of Butch’s outlaw career), Will Simpson (prosecutor at Butch’s trial in 1894) and James Simpson (Will Simpson’s son). Governor Richards and Will Simpson were at least possible sources for Bechdolt’s account of the Cassidy-Powers meeting. However, neither man was on the scene at the time of the meeting nor even indirectly involved in the incident.

But what about Bechdolt himself? Although born in Pennsylvania, Frederick Ritchie Bechdolt (1874-1950) grew up in the West and attended the University of North Dakota and later the University of Washington. Following graduation from the latter in 1896, he was hired as a reporter by the Seattle Star. He soon moved on, and for the next 10 years he wrote for major newspapers in Oakland, Los Angeles, San Francisco and Salt Lake City. Reporters find ways to dig out information. Being on the scene in Salt Lake City, possibly during the same year the Cassidy-Powers meeting took place or at least shortly thereafter, it is possible Bechdolt could have obtained the story, maybe even a stenographer’s record of the meeting. (Despite an obligation to keep information confidential, attorneys will tell you off the record that law offices can become leaky places when famous clients are involved. It was probably no different in those days.)

Thus Bechdolt’s proximity to Powers could explain his version of the meeting, as well as give his account some credibility, but what about Kelly’s version? It is possible that he also might have had contact with persons who had known Powers. Although Kelly was not around at the time of the Cassidy-Powers meeting, he did spend many years in Salt Lake City. In 1919, following discharge from the Army, he married and settled down there. However, at that time his primary interest was music (he played the violin and cornet), not writing. It would be another 10 years before he published his first book and nearly two decades before publication of The Outlaw Trail.

Of course, it is possible that Kelly simply rewrote the Bechdolt version. Kelly’s acknowledgments in the second edition of The Outlaw Trail reveal that he also had access to Bechdolt’s book when he wrote the first edition. In fact, in 1939, a year after the first edition was published, Kelly admitted in a letter to Cassidy’s prosecutor, Will Simpson, that Bechdolt was one of his “principal authorities” for The Outlaw Trail. But if he simply used Bechdolt’s version, why did he change it? Kelly was not averse to repeating verbatim earlier writers’ work, including Bechdolt’s (which he admitted in his letter to Simpson). However, he might have already lifted sizable portions of Bechdolt’s material on other aspects of Cassidy’s career and perhaps decided that he should give the conversation between Cassidy and Powers his own interpretation.

In any case, Cassidy was no doubt discouraged when he left Powers’ office that day in 1899, but he was not ready to give up. He knew of someone else in Salt Lake City who might help him, someone who might be more receptive to his pursuit of a pardon and, more important, someone who had even better access to Utah Governor Heber Wells than attorney Orlando Powers. That man was Parley P. Christensen.

In his book, Charles Kelly describes Parley Christensen as a former sheriff of Juab County, Utah, a man who knew Butch Cassidy in his early years. However, when I checked with Juab County officials, they could find no record of a Parley P. Christensen having ever been sheriff of that county. Local records did list a town marshal by that name for the city of Nephi, the Juab County seat, but he was not appointed until 1914.

Further digging revealed that the Parley P. Christensen from whom Cassidy sought help might have once been a sheriff, but by 1899 he, like Orlando Powers, had become a prominent Salt Lake City attorney. A graduate of the University of Deseret (later the University of Utah) and Cornell University School of Law, Christensen was a rising star in Republican politics and a familiar sight in the halls of the Utah Capitol. He and Governor Wells, also a Republican, were well acquainted, having both served as delegates to the Utah State Constitutional Convention in 1895. Christensen, in fact, had served as secretary of the convention and was later elected to the state Legislature. (During that same fall, Christensen was elected Salt Lake County attorney and seemed destined for the governor’s office, but several years later he had a falling out with the Republican Party and eventually joined the Progressive movement. In 1920 he ran for president of the United States on the Farmer-Labor ticket.)

Cassidy found Parley Christensen much more encouraging than Powers about his chances to obtain some form of clemency. Christensen quickly arranged an appointment for him with the governor. According to Kelly, after listening to Cassidy’s offer, Wells told him that if there were no murder warrants out for him, he thought something could be worked out. However, when the governor had his attorney general check the warrants on Cassidy, a murder charge did turn up. During a second meeting, the governor informed Butch that he was sorry, but there was nothing he could do for him.

Cassidy insisted that he had never killed a man in his life, but that wasn’t the issue. The governor’s condition had been that there could be no murder warrants out for him, and one was found. Frankly, Butch should have expected as much. After all, for the previous three years, when a bank or train robbery occurred in Utah or the surrounding states, Butch Cassidy and the Wild Bunch usually topped the list of suspects. If a bank or express car guard had been killed in one of those robberies, it is not surprising that Cassidy’s name was on a warrant.

According to Kelly, at this point attorney Orlando Powers reentered the picture. He had come up with a novel idea. What if Cassidy agreed not only to give up his life of crime but also to go to work for the Union Pacific Railroad as an express guard? If so, perhaps the railroad would drop all charges against him. As a fulltime employee of the railroad, Butch could not get away with much; his whereabouts would usually be known. Moreover, Powers could argue that, when other outlaws learned the famous Butch Cassidy was guarding the Union Pacific’s express cars, they might be hesitant to attack the train.

Author A.F.C. Greene does not mention Powers’ idea. Lula Parker Betenson, Butch’s younger sister, does refer to it in her book, Butch Cassidy, My Brother, but Kelly was probably her source. Frederick Bechdolt briefly discusses a variation of the story. He says Butch asked for a meeting with John Ward, sheriff of Uinta County, Wyo., at a mountain pass on the Denver & Rio Grande line. There, the wanted man informed Ward that he could “tell the railroads that they could take their gunmen off the trains,” that they “ain’t going to need ’em” anymore, because nothing “was going to come off, and you’ve got my word for that.” Bechdolt, however, does not mention that Cassidy would ask for any kind of deal.

What could Butch have gained from such an arrangement? Actually, not a whole lot. The Union Pacific officials could only forgive him for robberies on their line. At the time, the states of Wyoming and Utah wanted him, and Butch was also a suspect in bank or train robberies in Colorado, Idaho, Nevada, Montana and New Mexico. The Union Pacific officials could not grant amnesty for any of those offenses.

But what does give some legs to the story that Cassidy might have accepted Powers’ suggestion and offered to work for the railroad company is a letter found in the Utah State Archives’ collection of the correspondence of Governor Wells. The letter, addressed to Wells, was dated May 30, 1900. The writer was W.S. Seavey, then general agent of the Denver office of the Thiel Detective Service. Seavey wrote, “I desire to inform you that I have reliable information to the effect that if the authorities will let him alone and the UPRR officials will give him a job as guard, etc., the outlaw Butch Cassidy will lay down his arms, come in, give himself up, go to work and be a good peacable [sic] citizen hereafter.”

What adds to the letter’s credibility is that W.S. Seavey was not an ordinary part-time gumshoe. If Seavey considered his information as “reliable,” it probably was. Seavey might have been a careless speller, but he was an experienced lawman who, before becoming a Thiel general agent, had served eight years as chief of the Omaha Police Department.

Kelly tells us that Powers presented the offer to the Union Pacific, and “after some discussion the railroad officials agreed to the plan and authorized Powers to get in touch with Cassidy.” The author says Powers then wrote to Douglas Preston, Cassidy’s personal lawyer since the early 1890s, requesting that he get the word to Cassidy. He did, and, according to Kelly, Preston arranged to meet Cassidy in 10 days at “Lost Soldier Pass” in southwestern Wyoming and bring along the Union Pacific’s chief detective and “some officials with power to make an agreement.”

The meeting at Lost Soldier Pass never came off. As Kelly told it, Cassidy showed up, but there was no Douglas Preston and no railroad officials. After waiting all day, Butch rode back to his hideout. Preston later claimed that he and his party were delayed by a storm, and when they finally did arrive and found Cassidy gone, Preston, “disgusted with his fruitless effort, savagely kicked at a flat stone [that was] lying under the lone cedar where the meeting was to have taken place.” Underneath the stone he found a piece of paper on which Cassidy had written: “Damn you, Preston, you have double-crossed me. I waited all day but you didn’t show up. Tell the U.P. to go to hell. And you can go with them.”

It is not difficult to believe that Cassidy was tired of running and wanted to surrender, and that at the urging of Orlando Powers he would have considered working for the Union Pacific Railroad in exchange for amnesty. Unlike most outlaws of his day, Butch did not appear to have an aversion to honest work. Although he had committed his first bank robbery in 1889, there is no evidence that he was involved in another major crime for more than seven years, not until the bank robbery in 1896 at Montpelier, Idaho, to obtain money to help his friend Matt Warner.

It’s true that more than once during those seven years Cassidy probably helped himself to a rancher’s straying cattle, but among cowboys in Wyoming during the early 1890s, plucking a beef off the range was considered something akin to a part-time job. Butch also probably stole a few horses, which was looked upon more seriously (and for which he went to prison for 18 months).

And of course Cassidy has been credited with several major robberies during the last half of the 1890s; however, when he walked into lawyer Powers’ office that day in the fall of 1899 with the idea of surrendering, he had spent the previous year doing honest work, as assistant foreman and trail boss on the New Mexico Territory ranch of an Englishman, William French. It was hard, boring work ramrodding herds in the parched Southwest, but Butch Cassidy (known to rancher French as Jim Lowe) apparently enjoyed it. When the job of foreman opened up, he told French he wanted to take it, but by then the Pinkertons had come nosing around, and Butch felt it was wiser to leave. Years later, French had only good things to say about the man he knew as Jim Lowe.

Therefore, it is not difficult to believe that Cassidy probably would have succeeded as an express car guard. However, to think that the railroad would have actually hired him for that position is another matter. This is not to say that the idea was new. Hollywood writer-producer Glen Larson, who used just such an arrangement as a continuing plot for his 1970s Western TV series Alias Smith and Jones, claimed he got the idea from a reference to a similar arrangement he ran across while looking for story ideas in the files of the Pinkerton National Detective Agency. And in telling of the incident, Butch’s sister Lula (or her co-author, professional writer Dora Flack), while admitting that the idea of an outlaw becoming a railroad guard sounded pretty far-fetched, insisted that in Butch’s case it was no “fairy tale” and was “a plan familiar to lawmen.”

On the other hand, looking at such an arrangement from the railroad’s side, chances are the Union Pacific’s board of directors could not have stomached it. This group of investors had shelled out $110 million to purchase the line in 1893 and would have been more than a little nervous putting a known criminal on speeding trains that frequently carried thousands of dollars in bullion, coin and currency.

Moreover, it is difficult to believe that E.H. Harriman, then president and a major stockholder of the Union Pacific, would have gone for such a deal. Harriman was a problem solver, not a deal maker. For example, the previous year his answer to a flurry of train robberies was to station “posse cars” (gutted baggage cars loaded with experienced railroad police and former lawmen on fast horses) at strategic points along the line, ready to be dispatched at the first word of a holdup. And the plan was apparently working.

Furthermore, according to W.H. Park, then the Union Pacific’s general superintendent, at that particular time he and Harriman did not consider Butch Cassidy the most dangerous member of the Wild Bunch. They felt Harvey Logan deserved that title. Therefore, if presented with a plan for Cassidy to become an express car guard, Harriman and Park might have wondered just how much help Butch would be if a Harvey Logan–led gang of outlaws attacked one of their trains.

In addition, implementing such a plan would have been a major problem. With an outlaw on the railroad’s payroll and possibly in position to learn of shipment dates and security details, it is likely that Union Pacific officials would have accepted the deal only if they could have been assured that Butch would be kept under surveillance night and day. Was that possible? Probably not.

Also, the truth of the story of the aborted meeting between Cassidy and representatives of the railroad has been put further in doubt by recently discovered evidence. The “Damn you, Preston” note Butch allegedly left under a stone at Lost Soldier Pass might have been a forgery. Although Kelly spelled out the contents of the note in his book, it was assumed that the original note no longer existed—until sometime in the 1980s, when it mysteriously began circulating among rare document dealers. This caught the interest of writer Dan Buck, who, after several weeks of dogged detective work, discovered that the note might have been a creation of the notorious forger of Mormon documents, Mark Hofmann. It appears that Hofmann, or someone, might have written the note to conform to the story told by Charles Kelly. Although Buck hasn’t conclusively nailed down Hofmann as the culprit, he puts little faith in the note’s authenticity, as well as in the tale of the attempted rendezvous itself. In writing about the note and the alleged meeting, Buck, in the spring 2002 issue of The Journal of the Western Outlaw-Lawman History Association, raises several questions.

Preston was Cassidy’s old friend and defense lawyer. If he had failed to show up for a meeting, which, after all, was out in the middle of nowhere, would Cassidy have immediately accused him of a double-cross? Preston and his party were supposed to have been delayed by a storm. Would not Cassidy have weathered the same storm? The letter was written in ink. Would Cassidy have been carrying a pen and a bottle of ink in his saddlebags? And the note was not scribbled as it might have been by someone dashing off a message, perhaps using his saddle to write on. Instead, the handwriting was careful and neat, as if written on a desk. Cassidy supposedly hid the note under a rock, which just happened to be the rock that Preston, disgusted over Butch’s departure, “savagely kicked.”

Although Charles Kelly’s account of Cassidy’s aborted arrangement with Union Pacific officials now seems suspect, we should not come down too hard on Kelly. In The Outlaw Trail, Kelly did his best with the information he had, whatever the source. As tenuous as some of his facts might have been, Kelly provided a valuable starting point for subsequent research on Butch Cassidy and the Wild Bunch. And to his credit, in the first edition of his book Kelly admitted that his information was sometimes conflicting and indefinite, and because of this he invited his readers to write him if they had additional “facts,” so he could correct errors in future editions.

Dan Buck and Anne Meadows, in their introduction to the University of Nebraska Press’ 1996 reprint edition of The Outlaw Trail, aptly describe the challenge Kelly faced in telling Butch Cassidy’s story. They quote former Western Publications editor John Joerschke, who, in addressing a 1994 gathering of outlaw history aficionados, cautioned his audience: “If you want to write a true story, write a novel,” because the truth, the precious metal we seek, must be mined from “a mountain of lies, legends and missing clues.”

Richard Patterson devotes his time to legal writing and frontier history. His books Butch Cassidy: A Biography and Train Robbery: The Birth, Flowering and Decline of a Notorious Western Enterprise are recommended for further reading, along with Frederick R. Bechdolt’s Tales of the Old Timers; Lula Parker Betenson’s Butch Cassidy, My Brother; and the introduction by Dan Buck and Anne Meadows to the 1996 reprint of Charles Kelly’s The Outlaw Trail: A History of Butch Cassidy and His Wild Bunch.

Originally published in the February 2006 issue of Wild West. To subscribe, click here.