In 1777 a British general known as “Gentleman Johnny” sold the king on an audacious plan to end the American Revolution.

On March 27, 1777, King George III received Major General John Burgoyne at Saint James Palace, where, in a private audience, Burgoyne reviewed his audacious proposal to attack the rebellious American colonies “from the side of Canada.” If all went well, he said, the offensive would bring a speedy end to the American Revolution.

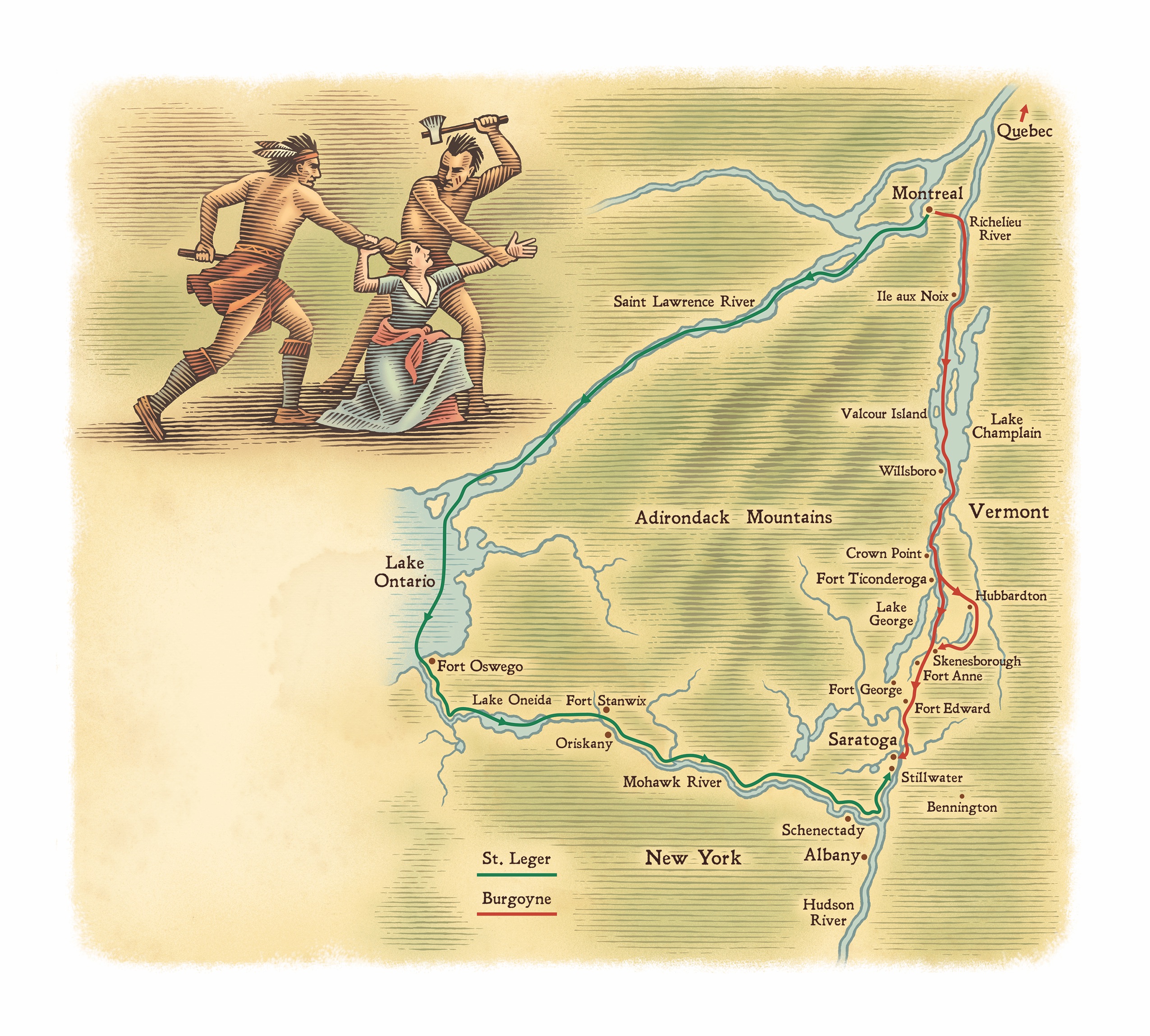

King George pored over the details of Burgoyne’s plan. It called for marching an army south from Montreal along the western shore of Lake Champlain, recapturing Fort Ticonderoga at the south end of the lake in New York, and then hurrying on to Albany in time to link up with an army led by General Sir William Howe, which would be marching north from New York City.

Burgoyne, the illegitimate son of a nobleman, had long since earned a reputation in London’s high society as a compulsive gambler—and the nickname “Gentleman Johnny.” After joining the British Army as a teenager and quickly rising through the ranks, Burgoyne had tapped his aristocratic wife’s dowry to buy a commission as a captain, but he then lost so much at the gaming tables that he had to sell the commission to cover his debts.

Commissioned again when the Seven Years’ War broke out, he distinguished himself as a risk taker, leading the Coldstream Guards on daring attacks in France and Portugal. His capture of the enemy’s commanding officer led to a promotion to major general and a seat in the House of Commons. Burgoyne had been posted to Boston as the Revolutionary War began at Lexington and Concord.

By that time the king’s privy council had banned the importation of weapons to the American colonies, but such a brisk contraband trade had sprung up that General Thomas Gage, the commander in chief of British forces in North America, had warned London that the radicals were “sending to Europe for all kinds of military stores.”

In May 1775, a full year before the individual colonial congresses deliberated independence, the Continental Congress appointed a secret committee headed by Robert Morris, who would almost singlehandedly arrange the financing of the Continental Army, to attempt negotiations with the French and Dutch governments for shipments of arms. Though these governments avoided direct complicity—supplying such contraband to the American rebels violated French neutrality under international law—they seldom interfered with entrepreneurs involved in the contraband trade. In France, Silas Deane, a Connecticut merchant and former member of Congress, acted as Congress’s commercial agent, working with Pierre-Augustin Caron de Beaumarchais, a playwright (The Marriage of Figaro) and arms dealer, to secure the secret approval of the foreign minister and King Louis XVI. They then set up a dummy mercantile firm, Roderigue Hortalez et Compagnie, to disguise their purchases of arms and ammunition in the Netherlands and other European countries.

Louis XVI, declaring that it was time to refit French weaponry, allowed merchants in Nantes to withdraw “outmoded” arms from royal arsenals for a nominal sum. Dutch arms mills were operating at full capacity. Gunpowder was shipped to Jamaica, where it was repackaged in sugar hogsheads and smuggled to Charleston, South Carolina; from Bordeaux, three hundred casks of powder and 5,000 muskets sailed for Philadelphia on ships flying French colors, to be hauled overland to Boston.

By the time Burgoyne was appointed in the spring of 1776 as second in command of the first British invasion from the north, a river of arms and ammunition was flowing to the American army through the Dutch Caribbean harbor of Saint Eustatius. There, the Americans paid Dutch merchants six times the going rates for such goods in Europe.

In 1776, to expedite the construction of a squadron to take control of Lake Champlain, the Royal Navy cut and numbered timbers in England and shipped them on the decks of troop transports to Quebec. There they were assembled into hulls and hauled over a muddy log road to be fitted out at the lake’s northernmost navigable point, just north of the Canadian border at Saint-Jean-sur-Richelieu.

To block the British, American brigadier general Benedict Arnold, having retreated from his failed invasion of Canada, began to build a fleet of 15 heavily armed row galleys at the southern end of the lake. Sir Guy Carleton, the governor general of Canada and commander of the British offensive, spent all summer trying to build a superior force. By the time he sailed south on October 11, snow covered the Adirondacks and the British sailors sleeping above decks.

In a savage battle that day, at point-blank range in the narrow channel behind Valcour Island, Arnold crippled the schooner Carleton before escaping at night, having lost his own flagship, Royal Savage. Then, in a four-day running encounter, he sank two more gunboats but saw 10 more of his own ships sunk, grounded, or captured before he carried his wounded south to safety at Fort Ticonderoga. A dazed Carleton arrived too late to attack the heavily defended fort. With thick snow falling, he rustled a herd of cattle and withdrew to Canada. Having squandered a season of war, he planned to resume the campaign the following spring.

Burgoyne had been forced to watch from the rear as his superior, Carleton, lacking artillery support, failed to use his army. Rushing back to London, Burgoyne drew up his “Thoughts for Conducting the War from the Side of Canada,” in which he laid out a second, bolder northern campaign. To avoid repeating Carleton’s mistakes, Burgoyne would combine heavy artillery with “savages and light forces” to force the Americans to retreat “without waiting for naval operations.” As part of the plan, Burgoyne proposed a diversionary attack from Lake Ontario down the Mohawk River to divide, draw off, and weaken American forces, making it more difficult for them to repel his main invading force.

King George responded to Burgoyne’s blueprint in his own handwriting, decreeing that the British invasion force be limited to a size that would not weaken Canada’s defenses. No doubt the king remembered the American invasion of 1775, when Montreal had fallen and Arnold had very nearly captured Quebec. “Not above 7,000 effectives can be spared over Lake Champlain,” the king wrote.

The king, who was of German descent, also thought Burgoyne undervalued the troops Britain could rent from his cousins. “The Diversion on the Mohawk,” he noted, “ought, at least, be strengthened by 400 Hanover Chasseurs.” While German generals were mostly seasoned veterans of European warfare, German soldiers, often misidentified as Hessians, were schoolmasters, tavern keepers, tramps, violinists—anyone the landgraves could round up and pack off to fight.

Although Burgoyne was reluctant to use Native Americans to fight the colonists, the king insisted on it. He also told Burgoyne to take and hold Lake George. Of paramount importance, the king stressed, was that “the force from Canada must join [Howe] at Albany.”

Burgoyne was promoted to lieutenant general and given command of the army that would invade New York from the north. The day after his private audience with King George, he left London for the port city of Plymouth to board the frigate Apollo for the 40-day winter crossing, pausing only to dash off a note to Howe detailing the king’s instructions. After arriving in Quebec, Burgoyne received his official written orders from Carleton.

Riding to Montreal, Burgoyne took personal command of his army. The invasion force was to be made up of 4,400 British Regulars and 4,700 Germans. The British units comprised 400 artillerymen and seven regiments of infantry, each made up of 500 to 600 men; the German units were to include 100 artillerymen and five regiments of infantry, each made up of 500 to 700 men, plus one regiment each of dragoons, grenadiers, and jägers (light infantry). In all, Burgoyne’s expeditionary force had 9,187 regulars (8,671 infantrymen and 516 artillerymen). He was required, however, to leave behind sufficient troops to garrison Canadian posts.

By the time Burgoyne was ready to march south from Canada, 886 regulars, 150 French-Canadian militia, two battalions of about 100 American loyalists, and some 400 Indians had been added. Burgoyne expected that far more loyalists would join him as he advanced into New York.

Burgoyne’s first setback was the poor turnout of French Canadian volunteers. He had hoped to draw on their experience in forest warfare, but their enthusiasm had evaporated with their defeat by the British in the Seven Years’ War.

By now Burgoyne’s invasion force had shrunk to 7,868 men, including 250 Brunswick dragoons. Aiming to reach the Hudson River quickly, he asked his commissary general to calculate the number of horses and wagons it would take to haul 30 days’ rations “and 1,000 gallons of rum” for 10,000 men. Even to transport two weeks’ supplies, he was told, would require 500 carts pulled by two horses each.

When Burgoyne told Carleton that he would need at least 800 to 1,000 horses, Carleton scoffed. He ultimately promised to procure them but never did, and Burgoyne could buy only 400 horses. The Brunswick cavalry, his eyes and ears for reconnaissance, would have to walk.

To besiege Fort Ticonderoga, Burgoyne had his choice of the cannons shipped from Britain a year earlier. From them Major General William Phillips, his chief of artillery, selected 144 cannons: 37 heavy guns, 12- and 24-pounders; 49 medium guns, 3- and 6-pounders; plus 58 howitzers and mortars. These weapons and their heavy ammunition were an impossible arsenal for horses to haul through the wilderness over rough, unpaved roads. Short on draft animals, Phillips had abandoned two-thirds of his heavy guns and all but nine of his medium guns after the army had marched just 60 miles.

Guns and infantry had to follow a centuries-old path along Lake Champlain. Mohawk Indians had worn ruts in the trail from Montreal, then called Hochelaga. By the time French explorer Samuel de Champlain stamped his name on maps of the lake between the Adirondack and Green Mountains, the Mohawks had retreated south.

As the English and French established fur trading empires in North America, the Indian trail had become a smuggler’s superhighway. Because the British at Albany offered better and cheaper trading goods that the French-connected northern Indians wanted, borderland Caughnawaga Iroquois, in bands of as many as 200, paddled, backpacked, or snowshoed heavy bundles of furs to Albany.

Building a fortress at Ticonderoga that they named Fort Carillon, the French had repulsed a British army in 1758, killing 2,000 men who attempted to take the fort without artillery. Two years later, the French retreated up the military road that had replaced the Indian path. Burgoyne’s infantry and supply train would follow the same route.

Burgoyne dispatched Brigadier General Simon Fraser with an advance guard of 10 companies of grenadiers, 10 companies of light infantry, and 3 companies of Carleton’s Canadians—about 1,300 troops in all—on a weeklong rapid march along the military road to secure a rendezvous point at the mouth of the Bouquet River. Fraser pitched camps straddling the river at Willsboro on the sprawling manor of loyalist William Gilliland. His men, thoroughly worn out from the march, set up what Fraser called “a pleasant and safe post…the most pleasant Camp I have ever seen.” While Fraser waited for Burgoyne, 200 Indians in birchbark canoes joined him.

Meanwhile, at Fort Saint John, on Ile au Noix at the northern tip of Lake Champlain, Phillips had loaded his artillery aboard the invasion fleet: the flagship Maria, the bomb ketch Thunderer, the sloop of war Inflexible, a row galley, a cutter, and, captured from the Americans the year before, the refitted schooner Royal George. Half the carts, hastily built of green wood at Montreal, had already fallen apart on the rough roads. Phillips ordered several of the ships stripped of their guns to make way for more supplies.

While his foot soldiers, camp cooks, and soldiers’ wives struggled for 12 days along the sodden road (it had rained for weeks; the path was a quagmire and swollen waterways had knocked out most bridges), Burgoyne and his generals sailed up the lake, reaching the Bouquet River encampment on June 20.

Convening a five-day “Congress of Indians” beside the falls of the Bouquet, the ever-theatrical Burgoyne read aloud a proclamation addressed to the king’s loyal subjects. He intended to inspire loyalists to join his campaign and terrify the rebellious colonists “to hold forth security not degradation.” Appealing to “the temperate part of the Public,” he decried the Revolution as “unnatural.”

He threatened the Americans, declaring: “I have only to give stretch to the Indian Forces under my command, and they amount to thousands, to overthrow the harden’d Enemies of Great Britain. Messengers of Justice and wrath await them in the field [with] Devastation, famine, and every concomitant horror that a reluctant, but indispensable prosecution of military duty must occasion.”

His Indian allies, mostly Iroquois but some Ottawa and Abenaki recruited in Canada, were resplendent in their war paint and regalia. In a forest clearing, Burgoyne treated them to a resounding oration. He cautioned them that this was a new kind of war. They were to kill only when ordered to do so by British officers:

I positively forbid bloodshed when you are not opposed in arms. Aged men, women, and children and prisoners must be held sacred from the knife or the hatchet. You shall receive compensation for the prisoners you take, but you shall be called to account for scalps…to be taken only from the dead.

After an enthusiastic chorus of “Etow! Etow!” an aged Iroquois chief gave an answering speech. Promising to obey all British orders, he sat down to another round of “Etow! Etow!” Then Burgoyne broke out the rum. All parties imbibed generously as the Indians celebrated with a war dance.

Burgoyne’s threat to employ thousands of Indian mercenaries was to prove extremely ill advised. Settlers who might have happily exchanged provisions for English gold began to hide the supplies and horses Burgoyne would so desperately need. As word of his threat spread throughout the frontier, militias began to form. On June 25, sufficiently recovered from Burgoyne’s hospitality, the Indians took their places in what may have been the most dazzling spectacle in the history of Lake Champlain. Recording the scene in his journal, Lieutenant Thomas Anburey wrote:

In the front, the Indians went with their birch canoes, containing twenty or thirty each; then the advanced corps in a regular line with their gunboats followed the Royal George and Inflexible towing large booms which are to be thrown across two points of land, with the other brigs and sloops following; after them the first brigade in a regular line, then the Generals Burgoyne, Phillips and Riedesel in their pinnaces [longboats]; next to them the second brigade, followed by the German brigades….

The generals stood at attention in their gunboats, as did the grenadiers of Fraser’s corps, their bayonets and brass fittings glimmering in the summer sunlight. Burgoyne, in scarlet uniform and gold epaulets, wore his dress sword and the trappings of the colonel of the Coldstream Guards.

Thousands of redcoats wore shortened coats and brimless caps, as an American privateer had captured the ship bearing their dress uniforms. The loyalists had dressed as Indians; the French Canadians wore white summer smocks; the Germans, light blue, green, or black uniforms.

Leading his light infantry in an amphibious assault on the old French works at Crown Point, 14 miles north of Fort Ticonderoga, Major Alexander Lindsay Lord Balcarres, 6th Earl of Balcarres, found the promontory deserted. On June 30, the army landed on both sides of the lake a few miles north of the fort as Burgoyne issued his final general orders for the campaign, urging “a reliance on the bayonet,” which “in the hands of the Valiant is irresistible….It will be our Glory and our preservation, to Storm when possible.”

By July 1, the army hove to just beyond cannon range. Burgoyne faced the fort’s walls across shoreline meadows that had been cleared of underbrush and trees to provide a field of fire lined with trenches. Across the lake’s narrow neck, the Americans had built an elaborate network of stockades and cannons on Mount Independence, connected to the fort by a floating bridge.

For months Colonel Tadeusz Kościuszko, a Polish-born, French-trained military engineer, had been urging the commander to fortify the highest hill just to the south, which was in easy range of the fort, but the American had ignored him. General Phillips, Burgoyne’s veteran artillerist, instantly grasped the importance of this weak spot. The engineer he sent to scout it reported that it could be climbed and was within 1,500 yards of the American fort.

On July 5, British soldiers overnight cleared a path to the summit, made gun emplacements, and hauled up two cannons. The first cannon fire from what became known as Mount Defiance the next morning convinced the fort’s recently arrived commanding officer, Major General Arthur St. Clair, that he must evacuate Fort Ticonderoga or risk losing his entire army. In a council of war, all the American officers supported him, voting to retreat under cover of darkness to minimize casualties and keep the army intact.

Nearly the entire garrison managed to escape. With five row galleys covering their retreat, the sick, the wounded, and the women were loaded onto 220 bateaux and sailed down Wood Creek to Skenesborough. With Fraser and his grenadiers pursuing them down the west shore of the lake and Major General Friedrich Adolf Riedesel and the Germans on the Vermont shore, all but 200 of the weary and dispirited Americans, aided by a fierce rearguard action at Hubbardton by the Vermonters, managed to escape south.

When a dispatch from Burgoyne reached London, the recapture of Ticonderoga made him a popular hero. When King George heard the news, he exulted to Queen Charlotte, “I have beat them, beat all the Americans!”

But once again Burgoyne squandered his advantage as the Americans employed a scorched-earth strategy. He landed three regiments at South Bay on the east side of the Ticonderoga promontory with orders to occupy the road to Fort Anne, the only route south, but moving his troops through the dense woods proved difficult. Once again, the Americans escaped, burning the fort at Skenesborough and destroying the bridges, rendering the road impassable; once again, they turned and fought a two-hour, rearguard action before they burned Fort Anne and retreated to Fort Edward. There, they joined St. Clair and the main army, which had escaped through Manchester and Bennington, Vermont.

Now Burgoyne faced a difficult decision, one that would prove controversial. In the plan approved by the king, he had proposed Lake George as the best route to Albany, a route that would take the army to Fort George, the northern terminus of a 16-mile road to Fort Edward and the portage to the Hudson River. He had believed it to be the shortest route from Ticonderoga to the Hudson and the least vulnerable to ambush, flank attack, and delaying action. He expected to capture the American army at Ticonderoga, but if the Americans retreated, he thought they would flee down Lake George. But St. Clair surprised him by retreating east through Skenesborough, his only feasible escape route with British guns atop Mount Defiance.

If Burgoyne had sent ahead his advance corps supported by light infantry to attack Fort Edward in July’s third week, he could have seized the fort before the retreating Americans could reinforce it. With his main army, Burgoyne could then have seized Fort George, cutting off St. Clair’s retreat. Embarking his entire army down Lake George, he might have crossed it in 24 hours. He could have then reached Albany by the end of July.

Instead, he chose to divide his forces, moving his troops along the land route east of Lake George from Skenesborough and sending his gunboats, bateaux, and heavy artillery over Lake George. Critics would later accuse him of choosing the slower land route under the influence of Colonel Philip Skene, the owner of the vast Skenesborough Manor, who would profit from an improved road with strong new bridges and causeways through swamps built by army engineers.

Later, Burgoyne would defend his choice of routes before Parliament by arguing that, after taking Skenesborough and Fort George, he would have had to fall back to Ticonderoga from Skenesborough, some 36 miles, then start the march south all over again. He contended that his advance would have bogged down, as his boats, artillery, and supply wagons portaged from Lake Champlain up to the level of Lake George, 221 feet higher via a gorge three miles long, a task that eventually took 11 days. From Lake George to the Hudson was another 16 miles, making the overall march 90 miles. Burgoyne saw such a retreat before advancing again as psychologically devastating to his army.

Burgoyne had made a reasonable command decision to send his foot soldiers by land and his artillery and supplies by boat over Lake George. The forces reunited at the abandoned Fort Edward within 24 hours of each other on July 28 and 29. In fact, ferrying the army the length of the lake would have taken even longer: There were not enough boats to transport the troops, guns, and supplies all at once. More hours would have been lost crossing the lake four times.

Time, not distance, now became Burgoyne’s enemy. All night, he could hear the dull thwack of axes and the crash of trees as Major General Philip Schuyler’s tireless army blocked the roads, slowing Burgoyne’s advance to a mile a day. Once again, the Americans had escaped.

By early August, Burgoyne’s supply problems had become alarming. Consuming their rations by the end of July, the British badly needed resupply, but more than anything they desperately needed more horses to haul food, tents, and winter uniforms over the lengthening line of communications to Canada—and the German dragoons were still on foot.

Burgoyne’s loyalist spies informed him that there was an American supply base at Bennington. Expecting to be able to either buy or confiscate some 1,000 horses, hundreds of cattle, large amounts of corn, and scores of wagons from the Vermonters, Burgoyne sent a force of nearly 500 men—230 Germans, 206 loyalists and Canadian volunteers, and 50 British light infantry under the Hessian colonel Friedrich Baum—to get the job done. Few of them, however, were familiar with the terrain.

Marching south first to Stillwater in the blistering August heat, Baum drafted another 100 Germans, then marched to Cambridge on the 12th. His advance guard surprised and captured 50 militia and seized 1,000 bushels of wheat and 1,500 bullocks. This too-easy victory encouraged Baum to march on to Bennington, where his spies told him there were 2,000 more bullocks and 300 horses guarded by only 1,800 Vermonters.

Despite being badly outnumbered, Baum plodded ahead. By August 16 he was encamped at an entrenched position on a hilltop overlooking the Walloomsac River, seven miles west of Bennington, when 1,600 Massachusetts, New Hampshire, and Vermont militiamen led by Brigadier General John Stark swept around Baum’s flanks and breached his frontal defenses in a two-hour battle.

It appeared that 600 reinforcements sent by Burgoyne would turn the tide of battle before Vermonter Samuel Safford arrived with 140 Green Mountain Continentals, giving Stark enough time to regroup for the German counterattack. Repeating their flank sweeps and frontal attacks until sundown, the Americans, now outnumbering the invaders three to one, killed more than 200 of the British, including the commanding officers. The surrender of Baum’s 1,400 troops to an American militia force that sustained only 30 casualties seriously damaged Burgoyne’s chances of recruitment and resupply and further bogged him down.

Meanwhile, what had been planned as a diversionary attack, at a strategic portage in the western Mohawk River Valley, also failed. With 1,800 men, mostly Indians and loyalists, British colonel Barrimore Matthew “Barry” St. Leger had besieged Fort Stanwix, garrisoned by 800 New York militia. Iroquois ambushed an American relief force at Oriskany, but the militiamen fought back fiercely. When General George Washington sent Benedict Arnold with 1,000 volunteers, the Indians fled, leaving St. Leger no choice but to retreat to Lake Ontario, freeing Arnold and his men to reinforce the main American army.

At the same time, the turnout of American militia was increasing steadily, especially after the scalping of Jane McCrae by Burgoyne’s Canadian Indians. McCrae, who was engaged to a loyalist officer on Burgoyne’s staff, lived on a farm near Fort Edward. Her fiancé had sent a party of Indians with a horse to bring her and her belongings to Burgoyne’s camp. She was accidentally shot three times by pursuing Americans before she was scalped by an Indian known as Wyandot Panther, who wanted the bounty Burgoyne had offered, equivalent to a barrel of rum, for any American scalp. When Panther arrived in the British camp, McCrae’s fiancé recognized her hair. No one, it was clear, was safe from Burgoyne’s murderous Indians.

The incident proved doubly damaging to Burgoyne, who wanted to execute Panther, but his staff warned him that if he did so, all the Indians would desert him. As it was, his show of displeasure was enough to cool the Indians’ interest. Where Burgoyne had counted on the support of thousands of Indians, only 400 had come south with him, and most had abandoned the British by early September.

Still resolved to press on to Albany, Burgoyne finally crossed the Hudson on September 13 and moved against the Americans, now 6,000 strong and entrenched on Bemis Heights, a densely wooded plateau south of Saratoga, in elaborate defensive works that Kościuszko had designed—and armed with French heavy artillery.

In July, Schuyler had complained to General Washington that he had no cannons, even as two French transports, Amphitrite and Mercure, arrived at Portsmouth, New Hampshire, in time, he wrote, to unload “more than eighteen thousand stands of arms complete, and fifty-two pieces of brass cannons, with powder and tents and clothing.” As Burgoyne’s army had inched its way south through the forest, a convoy of oxen had been dragging cannons and ammunition west over the mountains. Most of the Americans’ arms at Saratoga were now state-of-the-art, French-made weapons, enabling the Americans to fight the British invaders to a bloody standstill in two battles.

In the Battle of Freeman’s Farm, near Saratoga, Burgoyne’s attempt on September 19 to gain the high ground on the American left ran into the deadly accurate fire of Colonel Daniel Morgan and his riflemen. British casualties of 600 men were double the American toll.

Burgoyne became increasingly desperate. After waiting three more weeks, he learned that he could expect no help from Howe, who had defeated Washington at Brandywine Creek and, outmaneuvering him, captured Philadelphia and decided to spend the winter in the American capital.

On October 7 Burgoyne finally ventured out of his heavily fortified lines at Freeman’s Farm. Once again, he failed to turn the American left before Benedict Arnold, leading a fierce assault, drove him back into his walled log fort. Arnold was crippled by a wound to his leg, but not so much as Burgoyne, who had lost another 600 men (the American had lost only 150). Now he was surrounded by Americans, who outnumbered his men three to one.

Withdrawing from the battlefield that night, Burgoyne retreated to Saratoga. His path back to Canada cut off, his army now thoroughly demoralized, he surrendered his remaining 5,700 men—all that remained of 10,700 invaders—on October 17, 1777.

Burgoyne had sealed his own defeat not only by the route he had chosen but by his rash proclamation that he would enlist Indians to help him. Thousands of irate Americans handed the reckless commander a thrashing that roused international support for the American Revolution.

In the greatest American victory of the eight-year war, Burgoyne’s loss of an entire British army at Saratoga convinced the French that the Americans, with their help, could defeat Great Britain. Within months its Treaties of Amity and Friendship with France assured the infant republic enough military and economic assistance that it could survive as an independent nation.

France’s entry completely transformed the war. With French weapons and training in maneuver by Major General Baron von Steuben, Washington’s army marched out of Valley Forge in pursuit of the British as they retreated across to New York City. In hundred-degree heat at the Battle of Monmouth in June 1778, the reinvigorated Americans fought the British to a standstill.

As the American Revolution metastasized into a worldwide struggle between the British and allied American, French, Spanish, and Dutch forces, the British fought a largely defensive war of posts, rarely launching ambitious campaigns, their only major success at Charleston, South Carolina. Only once did Washington launch a major offensive, driving the Iroquois into Canada and destroying their western New York tribal lands.

The failure of Burgoyne’s invasion of America “from the side of Canada” led to a drawn-out, five-year fight that left him little more than a footnote to the narrative of a wider war. After he signed a convention of surrender that assured his army would be allowed to sail back to England, Congress rejected it, allowing only senior British officers to sail home. The rest of the Convention Army, as it had become known, marched south to sit out the rest of the war in Virginia and Maryland. Returning to England in disgrace, stripped of his command, “Gentleman Johnny” Burgoyne joined the opposition to the war in Parliament and returned to the one place he would ever again receive accolades—the London theater. To jeers and cheers, he became a popular, if second-rate, West End playwright.

Willard Sterne Randall, professor emeritus of history at Champlain College, is the author of 14 books, including Unshackling America: How the War of 1812 Truly Ended the American Revolution (St. Martin’s Press, 2017).

[hr]

This article appears in the Spring 2020 issue (Vol. 32, No. 3) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: Burgoyne’s Big Fail

Want to have the lavishly illustrated, premium-quality print edition of MHQ delivered directly to you four times a year? Subscribe now at special savings!