A new exhibit at the National Museum of the United States Air Force brings back memories of the “duck and cover” age, when reports of space invaders and flying saucers filled the news. During the late 1950s, the United States and Canada tested a vehicle that seemingly resembled a craft from another world. The once top-secret flying disk now on display at the museum is one of only two VZ-9-AV Avrocars built, the brainchild of British designer John “Jack” Frost.

Frost came to Avro Aircraft, Ltd. (Canada) in 1947 after a distinguished career with Britain’s de Havilland Aircraft Company, where he was instrumental in designing the jet-powered, twin-boom DH-100 Vampire, the twin-engine DH-103 Hornet and the tailless DH-108 Swallow. At Avro he created the Special Projects Group, which became involved in developing the CF-100 Canuck, the first and only Canadian-designed long-range jet fighter-interceptor to be mass produced. The CF-100, a conventionally designed airplane with straight wings and stabilizers, served with nine Royal Canadian Air Force squadrons in the mid ’50s.

Frost believed that in any future war concrete landing strips would be among the first targets; eliminating them would cripple, or at least delay, any air counterstrike by the opposing force. His proposed solution: squadrons of vertical takeoff and landing aircraft that would not need runways. Working on this principle, his team of Special Projects Group scientists and designers came up with a highly modified turbine engine that drove a centrifugal fan in the center of a spade-shaped vehicle, known as Project Y. The “pancake engine,” as Frost called it, produced a blast of air that created lift. A portion of the thrust could be vented through pipes on the outside of the airframe to push the aircraft forward, side to side or backward. Keep in mind that all of this was before computers were employed to take over the control problems presented by airflow dynamics.

In 1953 Frost induced a group of American defense experts touring the Avro plant to visit the Special Projects Hangar and look at secret models, mock-ups and drawings of his proposed VTOL aircraft. The visitors were so impressed that two years later the U.S. Air Force came up with a $750,000 contract for further development. The following year Avro committed $2.5 million more to the project. In March 1957, when the USAF dedicated additional funds to the undertaking, Project Y-2 became Weapons System 606A.

Development continued, with the team making improvements based on each wind tunnel trial. At one point Frost estimated that his VTOL aircraft could conceivably reach a top speed of Mach 3.5 at 100,000 feet. As the project’s size and cost ballooned, however, USAF brass began to question the legitimacy of Frost’s fighter concept. They believed that there was a much greater need for a proven long-range bomber and supersonic high-altitude interceptor.

At the same time, newspaper and magazine stories began appearing that speculated some UFOs were actually Soviet-built saucer-shaped vehicles. In 1955 Look magazine revealed some of Frost’s early circular design drawings, fueling speculation about the U.S. and Canada developing a flying saucer. In reality, Frost’s drawings of Weapons System 606A showed a saucer-shaped craft with a boom containing the cockpit grafted on the front.

By 1958, Frost had abandoned some of his early concepts and begun building a scaled-down machine he now called the Avrocar. At the same time the U.S. Army became interested in using such a vehicle as a “flying jeep.” Frost indicated that this smaller craft had the potential for a 10- minute ground effect hover capability, 25- mile range and the ability to transport a 1,000-pound payload.

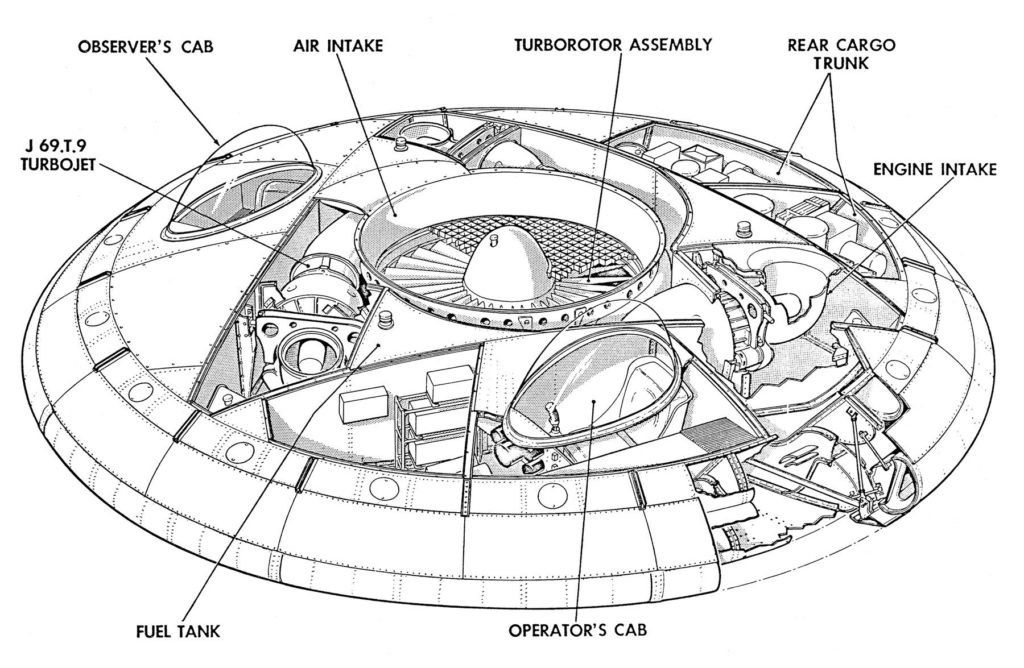

The vehicle was an aluminum-skinned disk, 18 feet in diameter and 3½ feet tall at the center. The internal structure consisted of a large metal equilateral triangular truss to which all the components were attached. The 124-blade “turborotor,” driven by three Continental J69-T-9 jet engines attached to the truss, was placed in the center of the craft, where the fan’s thrust was directed down. A pilot and an observer occupied two cockpits located on opposite sides of the disk, controlling the vehicle by directing the flow of high-pressure air with a side-mounted stick.

The Avrocar project was humming along when disaster struck in February 1959: The Canadian government canceled the Avro CF-105 Arrow supersonic interceptor program, and Avro laid off most of its employees, including those in the Special Operations Group. Thanks to political maneuvering, Frost got the Avrocar project continued, but only with U.S. funding. Development was abandoned by the early 1960s, however, as the Avrocar proved inherently unstable in forward flight.

NMUSAF historian Jeff Underwood noted that the Avrocar’s design is significant in that it demonstrates to what extent aviation was in flux at the end of World War II. “It shows that people had started really thinking out of the box at the time,” he said, citing the testing and development of such innovative aircraft as the Ryan X-13 Vertijet and the McDonnell XF-85 Goblin, a parasite fighter that was carried aloft on a trapeze-like rail beneath a Boeing B-36.

Underwood pointed out that prior to the Avrocar, designers looked only to attach a propeller to the front or rear of an aircraft or “put a jet engine on it to push air out the back end.” But when it came to the Avro car: “Now they are talking about taking a jet engine and pushing down for lift and to move back and forth. That’s pretty extreme stuff.” And while the Avrocar was considered a failure at the time, in retrospect it was more of a first step toward the principle of vectored thrust used so successfully by aeronautical engineers today.

The first full-scale prototype of the Avrocar, serial no. 58-7055, rolled out of the Avro Malton plant near Toronto in May 1959. It has been restored and was recently placed on display at the NMUSAF. Since it served as the wind tunnel test vehicle, this craft never actually flew. A second Avrocar logged about 75 hours in the field, eventually reaching a maximum speed of 20 knots and traversing a 6-foot-wide ditch at a height of 18 inches. In the end, however, lack of control as well as extreme heat and ear-splitting noise generated by the engines doomed the craft.

Restoration specialist Brian Lindamood explained that the museum acquired the Avrocar in 2007 from the Smithsonian’s Paul E. Garber Restoration and Storage Facility. Before restoration, Lindamood said, the vehicle was “in fairly rough condition, as it looked like it had been sitting in a high moisture area for some time.” Sections of its aluminum skin had to be sanded by hand to remove corrosion.

While its three Continental jets are still intact in the airframe, they’ve presumably not been run for almost 40 years. The 124- blade turborotor fan located in the center of the fuselage was cleaned up and polished and now appears factory fresh. “A lot of rivets had corroded out and were missing,” Lindamood said. “We replaced them so that there are no holes visible.” Then technicians swarmed over the aluminum-skinned craft with metal polish and buffers, resulting in a bright mirror finish that “you can almost see your face in,” according to Lindamood. Once the circular craft’s original markings had been repainted, the final step was heat-forming two new plexiglass canopy bubbles to cover its dual cockpits.

Ironically, if Jack Frost had added a rubber skirt to the outside of his flying disk, he would have produced the world’s first hovercraft. That milestone came a few months later, with the introduction of the Saunders Roe SR.N1.