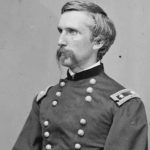

The 20th Maine’s epic stand and bayonet charge at Little Round Top on July 2, 1863, secured that regiment’s place in military history. During the second day of fighting at Gettysburg, commanders Colonel Joshua Chamberlain and Major Ellis Spear—already good friends from before the war—further forged a seemingly unbreakable bond in helping the Pine Tree State boys turn back Colonel William Oates’ relentless 15th Alabama and prevent a Confederate breakthrough on the Army of the Potomac’s left flank. Had the 20th Maine broken before the onslaught, it might have had a domino effect on other hard-pressed Federal units along Cemetery Ridge. The 20th’s stand was a critical moment in what became a Yankee triumph the following day.

Chamberlain and Spear both survived the war and lived long, prosperous lives, their friendship apparently firm. About 25 years ago, however, the story began to take root that Spear died embittered because Chamberlain—at the expense of him and others in the regiment—had claimed too much credit for their Little Round Top success in a postwar account. There are elements of truth in what we know today as the “Chamberlain–Spear Controversy,” but the notion that a blood feud existed between the two is far-fetched and worthy of further examination.

Spear and Chamberlain both grew up the oldest of four boys in families that had settled generations before in small shipbuilding communities upriver from the Maine coast. In the U.S. Census of 1860, Spear’s hometown of Warren had 2,300 inhabitants, Chamberlain’s Brewer 2,800. Both men would attend Bowdoin College in Brunswick, with Spear’s Class of 1858 studying under Professor Chamberlain, an 1852 graduate.

From letters between the two, it is clear that in college Spear was close friends with Chamberlain’s next younger brother, Horace. Though two years apart as students, they kept in touch, even visiting one another after graduation while each studied law. Horace might even have ended up the third Chamberlain brother to serve in the 20th Maine—along with Joshua and Thomas, the youngest—had he not died just nine months before the unit was formed.

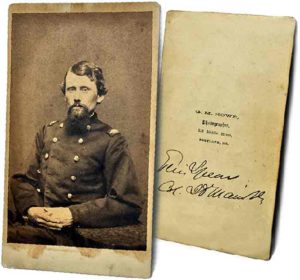

Spear and Chamberlain had a reunion of sorts when they found themselves serving in the same infantry regiment in the late summer of 1862. At the formation of the 20th Maine, Spear earned a position as captain, having recruited the bulk of the men for what became that unit’s Company G. Chamberlain did not personally recruit members of the regiment, but was granted a commission as lieutenant colonel—second in command—by the governor. During the war, Spear also looked after Thomas, taking him into his company, promoting him, and even recommending him for command of the unit when Spear himself was promoted.

In the postwar years, the affection Spear had for the senior Chamberlain did not abate. They corresponded, attended reunions and other events together, and shared a key role in memorializing their old regiment. In 1896, Spear wrote to Tom Chamberlain explaining his attempts to convince Congress to pass a bill raising the general’s pension from $25 a month to $100. “Please write me and advise me how he is and if he will probably be in Maine this Summer, and where.” Spear wrote. “I may have an opportunity to see him in the Summer and I hope to see you.”

Three years later, Spear was still advocating the pension increase. In a letter to Rep. Amos Allen (R-Maine), he wrote, “[Joshua Chamberlain] is seventy years of age, and is poor. He keeps up the best appearance he can, and is sensitive and proud, and is the last man to plead, or even admit poverty.” Spear added great praise for his former commander. “I was with him when he was wounded, and I know how severely it was. The common belief was that he would not recover from it. His is the most conspicuous and singular case in the State of distinguished service in the war, old and poor.”

Spear’s description of Chamberlain’s poverty may have been overstated—the old general owned a home in Brunswick, a larger summer home a few miles away, and a yacht—but the letters reveal a continued respect and admiration on Spear’s part and an active effort to care for his former comrade. Nevertheless, his efforts to aid in Chamberlain’s financial situation, even while conspiring with Tom to keep them from his brother, showed that Spear’s feelings were far more compassionate than anything else.

Whatever Joshua Chamberlain’s financial situation late in life, he did not decline an offer of $500 from Cosmopolitan magazine in 1912 to write a description of his role at the Battle of Fredericksburg for an issue celebrating the 50th anniversary of that battle. Nor was he deterred several months later when the same publisher asked for a similar piece on Gettysburg for Hearst’s magazine in 1913.

The original manuscripts of these two articles have never been found, so a detailed comparison of their original wording versus what appeared in print after editors did their work is not possible. Both magazines, however, were owned by William Randolph Hearst, the man who invented sensationalized journalism and was even blamed by some for starting the war between the United States and Spain in 1898. Although the story is likely apocryphal, Hearst is famously credited with dispatching the well-known illustrator, Frederic Remington, to Cuba to cover the war. Remington soon telegraphed home saying, “Everything quiet. There is no trouble here. There will be no war. Wish to return.” Hearst’s alleged reply was “You furnish the pictures, I’ll furnish the war”—and he did just that, using his newspapers to goad the U.S. government into declaring war.

Hearst’s editors no doubt followed their owner’s lead, tempting readers into buying copies of his magazines by publishing dramatically embellished stories that piqued the public’s interest, whether truthful or not. It is clear that editors took significant liberties with both pieces that Chamberlain supplied to Hearst periodicals, particularly the second piece on Gettysburg, which he wrote before he read the published version of his Fredericksburg essay.

When friends and admirers mentioned the Hearst’s article “Through Blood and Fire at Gettysburg,” Chamberlain chafed, lamenting that it “is much curtailed and changed by the insertion of ‘connective tissue’ by the Editor.” When a female admirer complimented him on the piece, Chamberlain replied, “The Hearst Editors mutilated and ‘corrected’ my ‘Gettysburg’ so that I have not tried to get copies of their magazine in which it appeared.”

Reading these articles greatly affected Spear, whose memories of the war were dark and tragic. He viewed these kinds of “vain glorious” writings as abhorrent, but never had the chance to discuss them with his former commander, who died within a year of publication of the Gettysburg article. Had he done so, he may have been surprised to find that the published versions were not to Chamberlain’s liking.

Without copies of Chamberlain’s original drafts, we cannot completely divine how much of each article came from his pen and how much was the exaggeration or invention of some sensationalizing Hearst’s editor. There are clues, however. For example, within the Gettysburg piece is a supposed letter, printed verbatim in complete form, from a 15th Alabama soldier who recalled that at Gettysburg he repeatedly had Chamberlain in his sights but “some queer notion” prevented him from pulling the trigger. He concluded by saying, “I am glad of it now, and I hope you are.”

Nowhere in all of the voluminous collections of letters that Chamberlain received in his lifetime does there exist either a copy of this letter or any mention of this episode. Yet Hearst’s published it in complete form. What can be found in one of these collections is a letter from a Bowdoin alumnus who, in 1903, visited a hotel in the South owned by a veteran of the 15th Alabama. In it, the historian passed on the veteran’s story of how he had fired at Chamberlain on Little Round Top, but “Chamberlain’s life was only saved by the act of a private who sprang in front of the Colonel and received the shot himself; killing him.”

While there is no direct evidence to support the notion, one can easily imagine that Chamberlain’s draft included a reference to this actual letter, from which the Hearst’s people imagined and actually created a similar but more dramatic tale and created an entire letter with which to dramatize it.

In an essay he never published, Spear analytically dissected Chamberlain’s “My Story of Fredericksburg” point by point, exposing what he saw as preposterous statements. Aged and infirm (he was 78 when the Gettysburg article reached print), Spear vented his frustrations at many of Chamberlain’s “memories” of these two battles.

Among the more revealing is the description in Chamberlain’s Fredericksburg account of when the regiment, on its way into the deadly maelstrom at Marye’s Heights, encountered a stray dog. In his memoirs, Spear recalled that during a lull, “[a] little dog came along whimpering with fright, evidently somebody’s house pet and I took him in my arms and held him while I remained there.” The story of the same wayward canine, however, appeared in Chamberlain’s Fredericksburg article quite differently: “My eyes were taken by the form of a yellow dog, sitting bolt upright with eyes fixed on his dead master.” The dog remained there fixated, loyal to the end, despite the whizzing of bullets and bursting of shells. “Indeed it would have been a pity, almost a sacrilege, to disturb that guardianship. And we left him there.”

That same section of the description of Fredericksburg included an encounter with a flock of doves that declined to escape the tumult, despite their ability to fly.

Whether these accounts were written as drafted by Chamberlain or were the partial or complete invention of some Hearst’s scribe intent on selling more magazines, we can only speculate. There is, however a telling remark, written by Chamberlain in the margins of an early printed copy sent to him for comment. Alongside this portion of the text he wrote, “Please oust dog & dove episodes.” Despite his plea, these melodramatic “episodes” remained in the final print.

If these clues about how the editors of early 20th-century magazines—at least those owned by W.R. Hearst—rewrote articles to please their readers, then the “vain-gloriousness” that Ellis Spear found so distasteful in the writings of his former friend, professor, commander, and fellow veteran, were merely the invention of someone other than Chamberlain. Were this the case, and if Chamberlain had survived long enough for the two old comrades to share their disgust with the outcome of these two literary efforts, Spear might have understood their true source and the so-called “Chamberlain-Spear Controversy” might never have come into being more than three-quarters of a century later.

Pine Tree State native Tom Desjardin is director of Maine’s Bureau of Parks and Lands. A former historian at Gettysburg National Military Park, Desjardin is the author of several books, including Stand Firm Ye Boys From Maine. He also was a consultant for actor Jeff Daniels during the filming of the 1993 film Gettysburg.

Invented Controversy

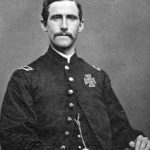

In his 1883 book Army Life, Private Theodore Gerrish wrote about his service with the 20th Maine during the Civil War. Gerrish claimed that on July 2, 1863, Colonel Joshua L. Chamberlain did not lead the regiment’s decisive bayonet charge after its one-hour stand at Little Round Top, bestowing that honor instead to the regiment’s Lieutenant Holman Melcher: “With a cheer and a flash of his [Melcher’s] sword that sent an inspiration along the line, full ten paces to the front he sprang—ten paces—more than half the distance between the hostile lines…‘Come on! Come on! Come on boys!’ he shouts. The color sergeant and the brave color guard follow, and with one wild yell of anguish wrung from its tortured heart the regiment charged.”

Gerrish, though, should not be considered a Gettysburg expert. In fact, from April 7 to August 23, 1863, he wasn’t even with the regiment, confined instead to a series of Union hospitals. While his comrades swept down Little Round Top, Gerrish was in a hospital ward just outside Philadelphia. More than six weeks passed before he even heard a description of the charge by a participant.

In reality, neither Chamberlain nor Melcher led the charge, which moved in the manner of a gate swinging open. Positioned as both were at the center of the line, they could not have initiated the required wheeling motion. Had the charge begun at the center, the 20th would have broken into two pieces at the colors—an inevitable disaster.

Melcher, it must be noted, never said he led the charge, nor did anyone other than Gerrish. A revealing account of the event, including Melcher’s role in it, is in the Bowdoin College archives. In an 1882 letter to Gerrish, then writing his regimental history, Chamberlain explained that he and Melcher were close during the charge and that Melcher may have saved his life.

“I went for the Color then at the angle in our center and the Color bearer was beside me advancing when Lieut. Melcher came dashing in and right up to my side,” Chamberlain wrote. “I was then in front of the commanding officer of the advancing front line of rebels [Lieutenant Robert H. Wicker, 15th Alabama]. He fired one shot… at me and I raised my saber to give him the point when he handed me his sword and pistol…and called out, ‘We surrender.’”

That means Melcher arrived behind Chamberlain just as the 20th reached Wicker’s line near the southern foot of Little Round Top. Chamberlain also noted that Sergeant Andrew Tozier, the unit’s color-bearer at Gettysburg (who lived with Chamberlain for a time in the late 1860s), concurred with his recollections, writing, “I have often talked with [him] since, and I have also his distinct memory.”

Contrary to criticisms that Chamberlain was attempting to glorify his own role in the charge, his account actually credits Melcher with saving his life and perhaps even the regiment’s success that day.

“I was glad to see you do justice to Major Melcher,” Chamberlain told Gerrish. “He was one of the coolest and most faithful officers. A man to be counted on always….I think it was the sight of Melcher and his squad coming down like Tigers that both made [Wicker] quit firing on me and surrender….Had not Melcher come on I think this officer would have shot me (4 barrels were loaded when I took his pistol) and very likely his men would have got such headway they might have swept us all back.”

In 1897, Chamberlain wrote to the War Department recommending Medals of Honor for Tozier and Melcher. Tozier’s was approved, but Melcher’s wasn’t.–T.D.