Frederick Handley Page produced the RAF’s first successful strategic bombers.

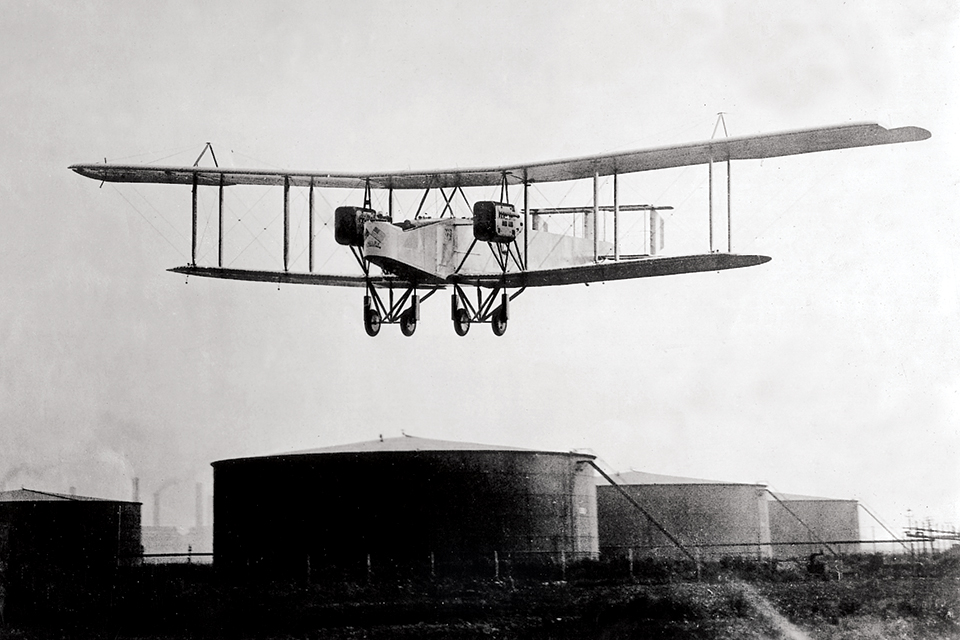

The first really large bombers to be produced in substantial numbers and employed in massed formations in a coordinated strategic offensive, the Handley Page O/100 and O/400 set the basic layout for both British and American bomber design. That pattern can be directly traced from the Handley Page bombers to the Royal Air Force’s V-bombers and the U.S. Air Force’s Boeing B-52.

Only two weeks after its founding on April 1, 1918, the fledgling RAF established the Independent Force, the Allies’ first dedicated strategic bombing organization and the direct ancestor of RAF Bomber Command. The Independent Force deployed massed formations of bombers against strategic targets far behind enemy lines in France, Belgium and Germany. Such a campaign would have been impossible had not a large twin-engine, long-range bomber already been in production: the Handley Page O/400. So many O/400s were built that during World War I and for some time afterward all large British aircraft were referred to as Handley Pages.

The RAF might never have been able to deploy its strategic bombing force in 1918 had it not been for a specification issued by the Royal Navy back in December 1914, when it was assigned the task of defending British airspace from German Zeppelin airships. Fortunately for Britain, one of the very few people who understood the potential of aviation, Captain Murray Sueter, was the head of the Admiralty’s Air Department.

Previously commander of the Royal Navy’s submarine forces, Sueter visualized the airplane’s possibilities as an offensive weapon when he took charge of the Air Department in August 1914. In September, he contracted with Short Brothers to produce the world’s first aircraft specifically designed to launch a torpedo, the Short Type 184. In December of that same year, Sueter issued another specification for a longrange bomber capable of attacking Zeppelin bases.

What Sueter had in mind was a twin-engine, armor-plated bomber that could carry a crew of two, six 100-pound bombs, 200 gallons of fuel and a wireless transceiver. Among the very few aircraft manufacturers willing to tackle such an ambitious project was Frederick Handley Page.

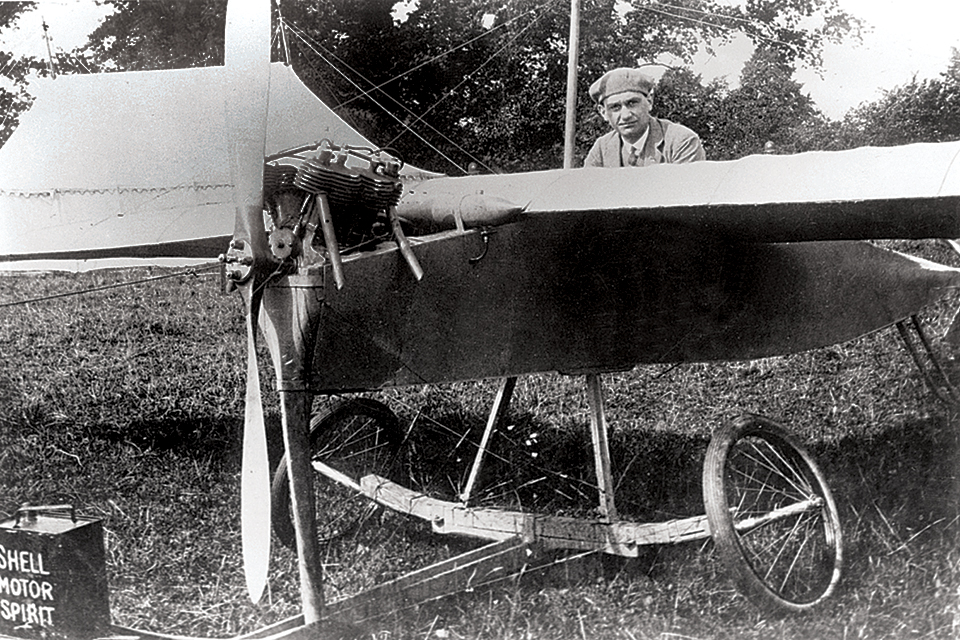

Born in 1885, Handley Page spent his early life studying electrical engineering, but in 1906 he became interested in aviation. The chief engineer at an electrical firm, Handley Page was eventually dismissed for spending too much of the company’s time on aviation experiments. He soon set up shop on his own, however, establishing Britain’s first publicly traded aircraft company in 1909. The following year Handley Page built his first successful aircraft, the 20-hp Type A monoplane. His most ambitious prewar project was the Type L, which he intended to fly across the Atlantic Ocean until war intervened in 1914.

Handley Page and his chief designer, George Volkert, met with Captain Sueter’s aviation technical adviser, Harris Booth, to discuss the plans for the new bomber. In describing what the navy had in mind, Booth alluded to a recent message from Commander Charles Samson, an officer serving in a Royal Navy armored car unit who was then trying desperately to stop the German advance through Belgium. Samson had declared that what Britain sorely needed was “a bloody paralyzer to stop the Hun in his tracks.” With that sentiment in mind, Handley Page and Volkert produced the Type O, later dubbed the O/100 in reference to its 100-foot wingspan. It was not only the largest aircraft Handley Page had built but also the largest plane constructed in Britain up to that time.

The prototype O/100 flew for first time at Hendon on December 17, 1915. It carried its two-man crew in an enclosed cockpit, an arrangement similar to that of its Russian contemporary, Igor Sikorsky’s Il’ya Muromets four-engine bomber. No gun positions had been provided in the O/100 because aircraft had not yet begun shooting at each other, but the cabin was armored against groundfire.

The O/100 prototype had been built in a remarkably short time considering the unprecedented scale of the project. Two of the landing gear’s four tires burst during the course of a laborious passage to the runway for its first test flight.

Many changes had to be made before the O/100 was ready for active service. A cylindrical fuel tank was installed above the internal bomb bay, increasing fuel capacity by 130 gallons. Operational developments over the front also dictated that consideration be given to self-defense. The enclosed cockpits and armor were replaced by additional open cockpits for front and rear machine-gunners.

The O/100 was an unequal-span biplane, with the top wing longer than the bottom wing. Ailerons were fitted only to the upper wing. Although never meant for shipboard operation, the O/100 had folding wings, so that the giant plane would fit in hangers. The tail was also of biplane configuration, with elevators on both surfaces. A fixed vertical stabilizer was installed between the tailplanes, flanked by twin rudders. Power was provided by a pair of 266-hp Rolls-Royce Eagle II water-cooled V-12 engines mounted on struts between the wings. The O/100 was 62 feet 10l⁄4 inches long and 22 feet high. It weighed 8,000 pounds empty and had a maximum takeoff weight of 14,000 pounds. The bomber’s maximum speed was 76 mph.

Production of the O/100 began slowly, and another year and a half elapsed before enough planes were available to equip an entire squadron in August 1916. Any “secret weapon” status it may have had was lost on January 1, 1917, when four O/100s took off for France. One plane got lost and landed at what turned out to be a German aerodrome, providing the enemy with a functional test specimen.

A few O/100s, armed with 6-pounder Davis recoilless guns in their nose cockpits, flew antisubmarine patrols over the North Sea early in 1917. On April 23, Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS) Flight Sub-Lieutenant T.S.S. Hood led five O/100s of No. 7 Squadron, operating out of Couderkerke, in an attack on five German destroyers off Blankenberghe. One of the planes’ 65- pound bombs scored a direct hit, causing one ship to list heavily to port. The other Germans dispersed, though they later returned to help their crippled sister ship limp back to port.

The principal users of the O/100s were two naval bombing groups, No. 5 Wing in Belgium and No. 3 Wing in France. The big bombers struck at their first land target on March 16, 1917, when an O/100 of No. 3 Wing attacked a German railway junction southwest of Metz. Thereafter No. 3 Wing flew night bombing missions against industrial targets in the Ruhr and Saar regions. Number 5 Wing carried out a highly effective night bombing campaign in Flanders, interdicting German supplies heading for the Ypres front.

Later in 1917, No. 3 Wing’s aircraft were transferred to Flanders to assist No. 5 Wing’s efforts to bomb long-range shore batteries and submarine bases in Belgium, and to support British army offensives near Ypres. On the night of July 2-3, for example, eight O/100s of No. 7 Squadron dropped 84 112-pound bombs on the Bruges docks, returning without loss. The next night, nine of the squadron’s planes hit airfields at Houttave, Ghistelles and Ostende, and another dropped 10 112-pound bombs on a train near Bruges.

One of the RNAS’ O/100s also saw service in the Aegean Sea. Flying from the isle of Mudros on July 9, Squadron Commander Kenneth Savory and his crew damaged the German battle cruiser Goeben at Istanbul. During an attack on railway targets near the Turkish capital on September 30, however, the Handley Page was struck by anti-aircraft fire. The pilot, Flight Lt. John K.W. Alcock, was forced to ditch in the sea, and all three crew members were taken prisoner. (Alcock would later achieve fame when he and Arthur Whitton Brown flew a Vickers Vimy on the first nonstop transatlantic flight, from Newfoundland to Ireland, in 1919.)

In the course of producing a total of 46 O/100s for the RNAS, Handley Page introduced a series of improvements that culminated in the O/400. The newer aircraft had a revised fuel system incorporating two 130-gallon fuel tanks within the fuselage above the internal bomb bay. A strengthened airframe enabled it to carry an increased bombload. The most important difference, however, was a welcome increase in horsepower, in a pair of 360-hp Rolls-Royce Eagle VIII engines.

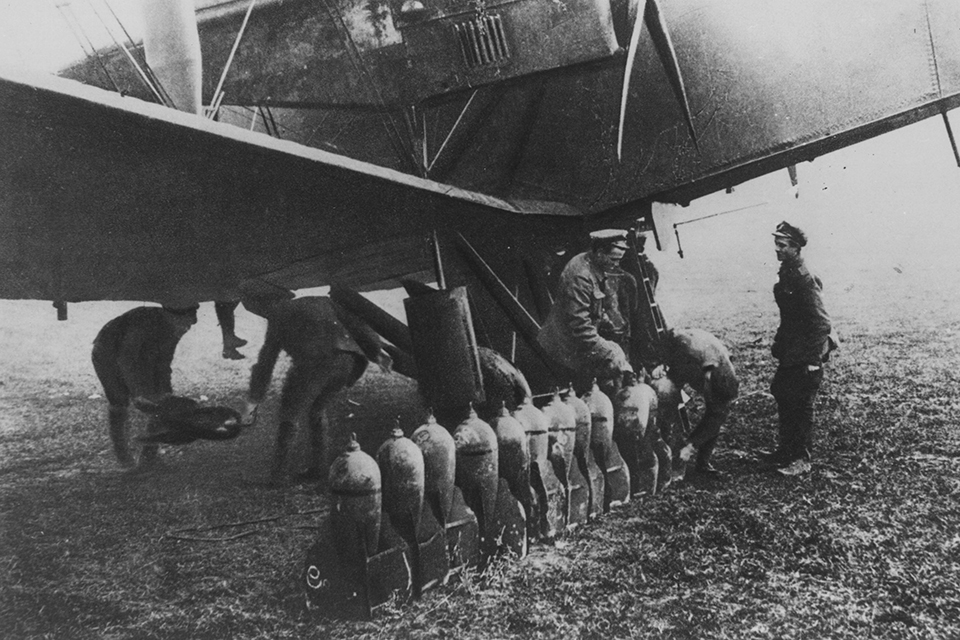

The Handley Page O/400’s cruising speed, 80 mph, was faster than the top speed of its predecessor. It had a maximum speed of 97 mph, could climb to 6,500 feet in 27 minutes and had a service ceiling of 8,500 feet. The internal bomb bay could accommodate 16 112-pound bombs, eight 250-pound bombs or three 520-pound bombs. The O/400 could also carry a single 1,650- pound bomb, the largest deployed by the RAF during World War I. Defensive armament comprised up to five .303-inch Lewis machine guns.

Like most subsequent 20th-century bombers, the Handley Page O/400 was laid out so that its engines were mounted in the wings in a tractor arrangement, with the propellers well clear of the fuselage. The bombardier-gunner occupied a cockpit in the extreme nose, and two pilots sat side by side in a cockpit directly behind him. The only difference between the basic arrangement of the O/400 cockpit and that of modern multi-engine aircraft was that the Handley Page’s senior pilot sat on the right rather than the left. Behind the pilots’ cockpit was a small cabin for a navigator’s chart table or radio equipment. Another gunner was accommodated aft of the bomb bay.

Although the Handley Page bomber was originally developed for the navy, the British army’s Royal Flying Corps (RFC) began to take an interest in it as early as February 1916, when it ordered a dozen O/100s for evaluation. Most RFC staff officers, however, still believed that large numbers of smaller single-engine tactical day bombers, such as the de Havilland D.H.4, would be more effective than fewer large long-range strategic bombers. That attitude changed in the summer of 1917, when twin-engine Gotha bombers began attacking London and other British targets. Ironically, the Germans initiated the Gotha strikes as retaliation for Handley Page raids against their military installations at Ostend and Zeebrugge, in occupied Belgium.

Public indignation over the Gotha raids compelled the RFC to establish its own heavy bombing force, for which the O/400 was the only suitable plane available. In fact, the British bomber was substantially larger than its German counterpart. The O/400 operated at a gross weight of 14,425 pounds, which was 68 percent greater than that of the Gotha, and could carry nearly twice the bombload over a mission radius of 300 miles. Consequently the British War Office ended up placing far larger orders for Handley Page bombers than the Admiralty had.

The RFC’s first operational heavy bomber unit, the 41st Wing, initiated bombing operations against industrial targets in the Ruhr and Saar on October 17, 1917. Like the German Zeppelins and Gothas, the British strategic bombers flew at night to avoid interception. As the war progressed, as many as 40 O/400s might participate in each mission. The targets included industrial centers in cities such as Koblenz, Metz, Cologne and Stuttgart. Favored targets included U-boat bases, railroads, blast furnaces and airfields.

Carrying out WWI night bombing missions was no easy task. The big Handley Pages lacked power-assisted controls, and thus were heavy and sluggish in the air. The engine instruments were located out on the engine nacelles, where distance from the cockpit and vibration made them difficult to read. Flight instruments were rudimentary and navigational aids virtually nonexistent. Pilots found their targets by dead reckoning and located their own bases by means of characteristic lights the various airfields displayed.

British pilot Cecil Lewis claimed the O/400 was “like a lorry in the air. When you decided to turn left you pushed over the controls, went and had a cup of tea and came back to find the turn just starting.” It was stable to fly, however. At least one pilot, Flight Commander T.C. Angus of No. 216 Squadron, contrived a homemade gyro horizon for his Handley Page, but night flying aids were by no means standardized.

The man behind the RFC’s—and later the RAF’s—strategic bombing program was Maj. Gen. Hugh Trenchard. One of the most remarkable and unlikely military officers of the 20th century, Trenchard failed his original army commissioning examination twice and barely passed the third time. Paralyzed from the waist down by an enemy bullet during the Boer War, Trenchard recovered the use of his legs (and revived his army career) after a freak accident in which his toboggan crashed into a tree. He learned to fly in 1912 at the relatively advanced age of 39. Trenchard was never regarded as more than an indifferent pilot. But he made up for his lack of flying skill with a clear vision of how to utilize military air power, as well as a knack for the training and organization needed to bring his ideas to fruition.

Trenchard commanded one of the three RFC wings deployed on the Western Front in November 1914. So aggressively and successfully did he use his aircraft in support of the army that in August 1915 his command was extended to all RFC units on the Western Front. It was only natural, then, that Trenchard became the first commanding officer of the RAF when the RFC and RNAS were merged to form that organization, the world’s first air arm not affiliated with either the army or navy, on April 1, 1918. He resigned shortly thereafter due to political differences with the secretary of state for air, but Trenchard promptly returned to active duty to organize the new Independent Force strategic bombing formation. Although intended as an interAllied arm, the Independent Force remained a mostly British organization until the end of the war, due to differences in opinion between the British and French over where and how their bombers ought to be utilized.

One of Trenchard’s most energetic apostles was the commander of the U.S. Army Air Service, Lt. Col. William Mitchell, who made a point of seeking out the RFC general soon after his arrival in Europe in the spring of 1917. Billy Mitchell, whom Trenchard called “a man after my own heart,” embraced his ideas on the effectiveness of large strategic bombers. It was no coincidence that the Handley Page O/400 became one of the European aircraft selected for licensed production in the United States. The Standard Aircraft Corporation of Plainfield, N.J., which was contracted to build 1,500 of the big bombers, modified the design to accept the obligatory 400-hp Liberty engines that the American automobile industry was turning out by the thousands. A total of 107 Handley Page bombers were manufactured in the United States by the time production was canceled at the end of the war, but none saw action in Europe.

Most of the Standard-built O/400s were shipped to Britain, where they were used to provide spare parts for the RAF’s Handley Pages, but Mitchell managed to acquire eight examples in 1919. At least one O/400 is reputed to have taken part (along with six newer Martin MB-3 bombers) in sinking the captured German battleship Ostfriesland with 2,000-pound bombs on July 21, 1921—part of Mitchell’s dramatic demonstration that capital ships were vulnerable to air attack.

Both the RAF and the U.S. Army conducted postwar studies on the results of the strategic bombing offensive. A total of 641 people were killed and 1,262 wounded in the Allied raids, and an estimated 35 million marks’ worth of damage was inflicted upon German targets. Both studies concluded, however, that the attacks’ effect upon German civilian morale far exceeded the modest damage done, in much the same way as when the Germans bombed London. Closing down industrial production during air raids cost the German war effort an estimated 71 million marks in war materiel. In addition, many factory workers refused to remain at their jobs during alerts unless they received bonuses, the cumulative cost of which added up to another 4 million marks.

The U.S. Army also estimated that the German government spent 85 million marks on air defense, including fighters, anti-aircraft guns and barrage balloons. The Germans diverted thousands of troops and much materiel from the Western Front to home defense, including at least 14 badly needed fighter squadrons.

The RAF developed one further version of Handley Page’s brainchild before the war ended. In direct response to the 1917 Gotha raids on London, the RAF requested a plane capable of bombing Berlin. Handley Page’s answer was a scaled-up O/400 with a 126-foot wingspan and a gross weight of 30,000 pounds. The huge plane was powered by four 360-hp Rolls-Royce Eagle engines, one pair that powered tractor airscrews and another that drove pusher propellers. With a top speed of 99 mph and a service ceiling of 11,000 feet, the V/1500 could carry 7,500 pounds of bombs and had a range of 1,300 miles. First flown in May 1918, the new plane was accepted for production, but only three V/1500s had entered service by the time the war ended. Though the huge bombers never saw action against Germany, one of them became the first plane to fly from England to India. When war broke out on the Northwest Frontier in the spring of 1919, the V/1500 was used to bomb Kabul, Afghanistan.

With the end of WWI, several O/400 squadrons converted their aircraft for use as mail and passenger transports. Frederick Handley Page founded an airline of his own, Handley Page Transport, for which he developed a modified civil version of the O/400. Known as the W-8 and first flown in 1919, the Handley Page airliner could accommodate up to 12 passengers. In 1924 Handley Page Transport merged with three other British airlines to form Imperial Airways, Britain’s first national airline and the forerunner of today’s British Airways.

Late in 1919, Handley Page patented his design for a wing leading edge slot. An aerodynamic feature that reduced the stalling speed and improved the low-speed stability of airplanes, the leading edge slot was a significant contribution to air safety that is still used today.

In addition to his efforts to promote British commercial aviation, Handley Page continued producing large night bombers for the RAF throughout the interwar period. Thousands of twinengine Handley Page Hampden and four-engine Halifax bombers saw action during World War II. The Halifax alone made up 40 percent of RAF Bomber Command’s aircraft. Frederick Handley Page was knighted in 1942 for his contribution to the Allied war effort.

After WWII the company continued producing large airliners, cargo planes and bombers. Its last bomber was the four-jet Victor, part of the RAF’s nuclear deterrent in the 1950s. When Handley Page died in 1962,his company was still Britain’s leading producer of large planes. After struggling to maintain its independence in the face of Britiain’s policy of corporate nationalization, the company finally went out of business in 1970.

The Handley Page O/400 was not the first large multiengine airplane. That distinction belonged to Russia’s four-engine Bolshoi Baltitsky, built by Igor Sikorsky in 1913. Nor was it the largest airplane of its day; Germany’s gigantic Riesenflugzeuge, or “R” planes, were much larger and more complex. Sikorsky’s wartime Il’ya Muromets fourengine bombers were relatively few, however, and were used in a piecemeal manner. Except for a handful of ZeppelinStaaken R.VIs, virtually every German Riesenflugzeug was a handmade prototype, and they never constituted a truly viable strategic bombing force. The O/400, on the other hand, was built in larger numbers and constituted a far more potent strategic bombing force than any other large aircraft of WWI. As a consequence, Handley Page bombers demonstrated the future potential of air power more effectively than any other aircraft of their era.

Robert Guttman is a frequent contributor to Aviation History. For further reading, he recommends: Handley Page: A History, by Alan Dowsett; and Trenchard at the Creation, by Rebecca Grant.

Originally published in the March 2007 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here.