Journalism can be a dangerous business. In 2018, according to the International Federation of Journalists, 94 reporters were killed in the line of work. That is far from a modern-day phenomenon. As then apprentice newspaperman and later Western literary star Bret Harte discovered, telling it straight about the unspeakably murderous reality of 19th-century California made you a target.

Harte’s trial by fire took place in the northern coastal town of Union (present-day Arcata), some 80 miles south of the Oregon border. Union flourished after its 1850 founding on Arcata Bay as a provisioning port for gold mines in the mountainous backcountry. But as redwood timber operations eclipsed mining, cross-bay rival Eureka surpassed Union and supplanted it as the Humboldt County seat. In 1857, a 20-year-old Harte arrived in the slowly fading settlement to visit half-sister Maggie.

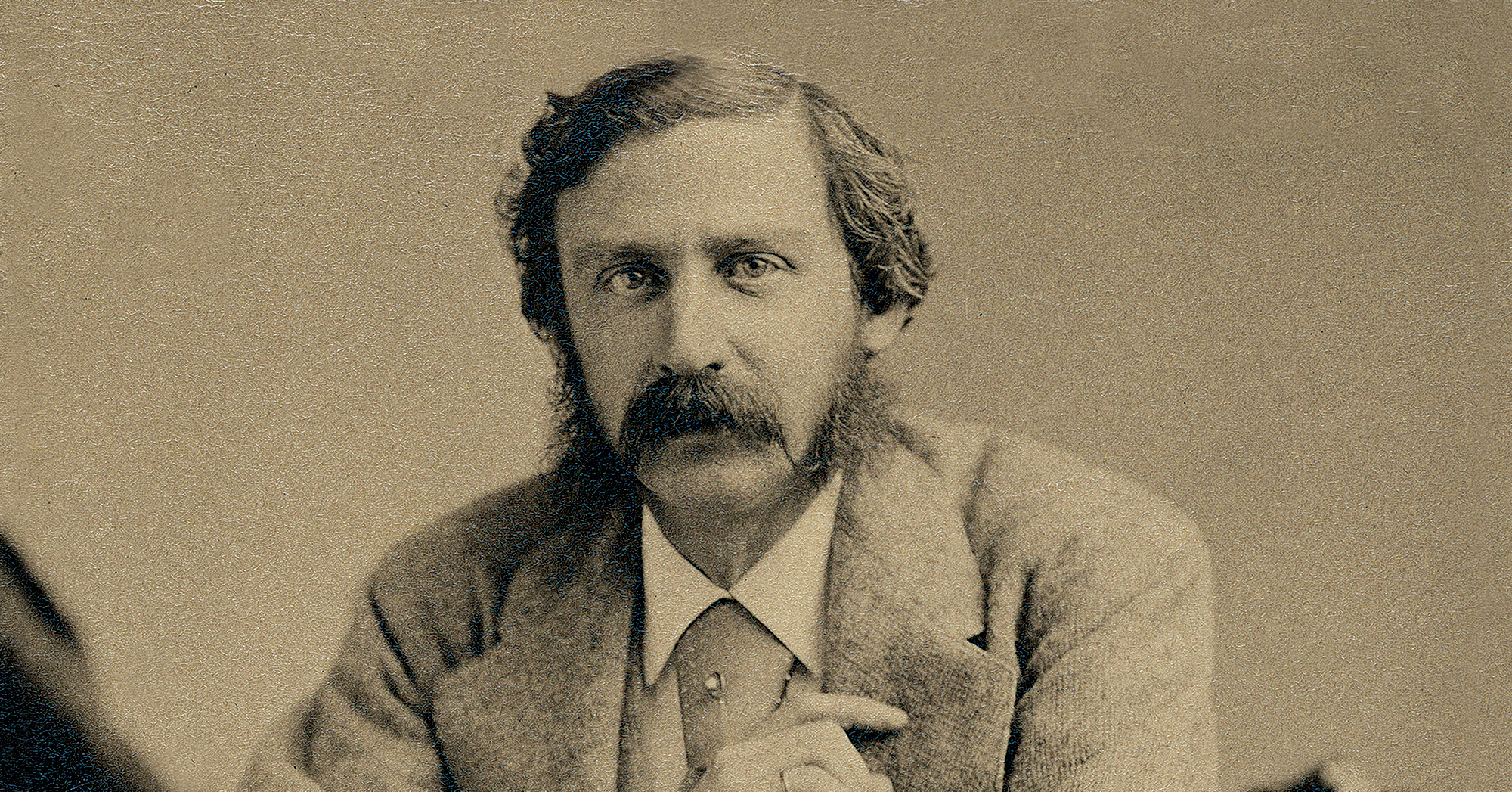

Harte had ventured west a few years earlier from his hometown of Albany, N.Y., to join his widowed and recently remarried mother in Oakland. He soon struck out on his own, later claiming he had panned streams in the Sierra Nevada goldfields and rode shotgun on stagecoaches. In truth, he spent little if any time at either pursuit, making his frontier living as a schoolteacher and tutor while entertaining the dream of becoming a famous writer. Hoping to stay on in Union, Harte found work tutoring the two teenage sons of a prosperous farmer. A soft-spoken and small but wiry man, he hunted the bay and estuaries for birds after lessons and established a reputation as a good whist player.

A year after Harte’s arrival in Union the town lost its newspaper, The Humboldt Times, to Eureka. The jilted settlement’s citizens got behind the efforts of Albert H. Murdock and Stephen G. Whipple to fill the journalistic void with The Northern Californian, a four-page weekly under Whipple’s editorship. It was to this modest news organization that Harte, ready to move on from tutoring, came looking for a job.

And he found it, as a “printer’s devil,” a notoriously dirty pressroom task that challenged Harte’s fastidious, well-dressed style. He soon proved himself in the newspaper business, however, and Whipple began sending him out on small reporting assignments. As Harte developed his skills, Whipple effectively promoted him to assistant editor, leaving the young man in charge whenever he went out of town on business. It just so happened Harte was at the editorial helm the last weekend of February 1860 when a dark reality of California’s early history surfaced in and around Arcata Bay.

Since 1851 the powers that be in the state had made it clear the solution to the Indian “problem” was extermination—genocide in modern legal parlance. “The two races are kept asunder by so many causes and, having no ties of marriage or consanguinity to unite them, must ever remain at enmity,” Governor Peter Burnett proclaimed in California’s first “State of the State” address. “That a war of extermination will continue to be waged between the races until the Indian race becomes extinct must be expected.”

It was hardly empty political rhetoric. Over the next few years, the California Legislature passed bond measures totaling $1.5 million (some $45 million in today’s dollars) to fund “expeditions against the Indians.” The money went largely to pay for local militias that ranged out from the settlements to shoot any recalcitrant Indians and round up the survivors for removal to reservations, where miserable conditions and starvation rations killed as surely as rifle balls.

Humboldt County had already been the site of several such militia campaigns, targeting Indian communities that, driven to near famine by the massive influx of whites, had resorted to rustling livestock for food. Such death squads killed Indians by the hundreds. In return the Legislature reimbursed the militiamen for expenses and compensated them for their time afield. Indian killing was a profitable proposition.

It enjoyed popular support, too—usually tacit, sometimes explicit. The Humboldt Times, for example, openly advocated for Indian extermination. In 1858, editor Austin Wiley wrote that the only way to prevent Indian troubles was “by removing them from the range they now inhabit, either alive or dead.” There’s no evidence the paper’s readers objected.

Eureka and Arcata thus far had been spared both Indian depredations and militia reprisals, as the local Wiyots, who had greeted the first white newcomers with a giant clambake, continued to make every effort to coexist and assimilate. Regardless, these peaceable people soon became the target of the most notorious massacre of Indians along California’s north coast.

Around New Year’s Day 1860, a group of local whites decided to stage a bloody display against Indian rustling by attacking people who had nothing to do with it—the Wiyots. The mob, which numbered some 50 to 75 men referred to pejoratively as “the Thugs,” was led by Henry P. “Hank” Larrabee, an Eel River rancher who once boasted of having personally killed 60 Indian infants with a hatchet. Swearing an oath never to reveal one another’s names, Larrabee and the others laid plans to kill as many Wiyots as they could in the most public way possible.

The closing days of February presented a perfect opportunity to act. Settlers from all over the region traveled to Eureka for the Humboldt County Court of Sessions, so the gathering of secretly sworn out-of-town killers hardly looked unusual. On Saturday, February 25, the day the court concluded its business, The Humboldt Times again reminded readers Indians would continue to kill stock in the backcountry “until they are driven from that section or exterminated.” Even as the paper hit the streets, the Wiyots and a visiting group of equally peaceful Indians from Mad River were celebrating their annual World Renewal Ceremony at the village of Tuluwat on Indian Island, in Arcata Bay a mile northeast of Eureka. The Wiyots danced and feasted into the night, then the men left the island by canoe to gather supplies for the next round of festivities.

The Thugs launched their assault that Sunday morning, February 26, around 4 a.m., after the Wiyot men had paddled away. Armed with hatchets, knives and clubs, a half-dozen intruders descended on the sleeping village, moving methodically house to house. They slaughtered the Indians by the dozens, cleaving skulls and slashing throats, chests and bellies. Women, elders, children, even babes in arms were butchered—some four dozen Wiyots all told. Only a handful of Tuluwat’s residents escaped by slipping away and hiding. Survivor Jane Sam, who gave an account of the massacre in the 1920s, saw two boatloads of white men row back to Eureka as the sun was rising. Before leaving, the murderers helped themselves to the Indians’ beads, baskets, furs and bows and arrows.

Tuluwat was only the most public slaughter site. On the same night and over the following five days, the Thugs hit nearly a dozen other Wiyot villages. Reports from the time are sketchy, but the vigilantes are believed to have murdered upward of 200 Indians.

As it happened, Whipple was heading to San Francisco through Eureka that fateful Sunday. He visited Tuluwat soon after the massacre and sent a vivid account back to Harte at The Northern Californian offices. Later that day, the young reporter himself saw the bodies of some of the Mad River Indians, which had been ferried by canoe to Union for transport to their home villages. The sight of the dead sickened and outraged Harte. With the next edition due out on Wednesday, he resolved to write well and truthfully about what he had seen.

Not that Harte was some bleeding-heart softy. In earlier reporting about Indians, he fell into stereotypical descriptions of them as slovenly, ugly and dirty. Against that backdrop, his newfound horror at the sight of butchered Indians was more remarkable. The young writer had been shocked into a moral awakening.

“Neither age nor sex had been spared,” Harte wrote. “Little children and old women were mercilessly stabbed and their skulls crushed with axes. When the bodies were landed at Union, a more shocking and revolting spectacle never was exhibited to the eyes of a Christian and civilized people. Old women, wrinkled and decrepit, lay weltering in blood, their brains dashed out and dabbled with their long gray hair. Infants, scarce a span long, lay with their faces cloven with hatchets and their bodies ghastly with wounds.”

Harte conceded past Indian troubles. If those who perpetrated the slaughter had good reason for it, he was willing to hear them. But he found it impossible to imagine how such an argument could be made. “We can conceive of no wrong,” he declared, “that a babe’s blood can atone for.”

And why, oh why, Harte wanted to know, did the extermination campaign target the most assimilated Indians in the region? The Wiyots were “peaceful and industrious, and seem to have perfect faith in the goodwill of whites. Many of them are familiar to our citizens.”

Despite the calculatedly public spectacle of the Tuluwat killings, the names of the Thugs remained unspoken. No one was claiming credit, a silence Harte took as evidence of community disapproval. “The secrecy of this indiscriminate massacre is an evidence of its disavowal and detestation of the community,” he posited. Well, not quite.

Harte was wrong in assuming the citizens of Eureka and Union universally shared his outrage and revulsion. Their silence in fact signaled most would go along with the Thugs. Not even the churches, those purported sanctuaries of moral uprightness, spoke out against the killings. “The pulpit is silent, and the preachers say not a word,” wrote a studiously anonymous correspondent to San Francisco’s Evening Bulletin. “In fact, they dare not.”

The Humboldt Times took Tuluwat as proof of the wisdom of continuing the extermination begun there. “For the past four years, we have advocated two—and only two—alternatives for ridding our country of Indians: Either remove them to some reservation or kill them,” editor Wiley reiterated. In his view, the mass killings constituted “proof that the time has arrived that either the paleface or the savage must yield the ground.”

Humboldt County Sheriff Barrant Van Nest launched no investigation into the Wiyot massacres. Rather, he collected signatures on a petition demanding state funding for a new militia campaign and in a letter to the Evening Bulletin defended the killings as rightful retaliation for rustling.

In part due to Harte’s coverage, word of the Humboldt massacres made its way into all the San Francisco papers, prompting a fierce editorial in the Daily Alta California condemning the state’s extermination policy. Soon, even the distant New York Times picked up the story.

Of course, the Thugs wanted no such out-of-town scrutiny, and they made it clear to Harte that journalistic righteousness had put his life and limb at risk. According to one likely apocryphal story, a cavalry patrol rescued Harte just as a lynch mob, noose in hand, was hauling him to a hanging tree. Another version had it Harte himself backed down the would-be hangmen with drawn pistols. Such hyperbole aside, Harte was indeed a marked man who needed to get out of town. One month to the day of the Tuluwat massacre, he boarded the steamer Columbia for San Francisco, never to return to the Humboldt coast.

Things turned out well for Harte, whose journalistic talents were in high demand in San Francisco. He landed a position at The Golden Era weekly and soon moved up to editor. In 1868, he was hired as founding editor of Overland Monthly magazine, in which he published the short stories that launched his career as an author in the United States and later in Europe.

Although Harte never again voiced explicit outrage over California’s maltreatment of Indians, here and there his fiction echoes the hard lessons of his time in Union. Consider Cherokee Sal in “The Luck of Roaring Camp,” the short story that, more than any other, advanced his status from unknown nobody to rising literary star. It offers a modern-day twist on the Nativity, with Cherokee Sal—a most unlikely candidate—in the role of Mary. “Dissolute, abandoned and irreclaimable,” in Harte’s words, she is “coarse” and “very sinful,” the one and only woman in Roaring Camp, where, the story implies, she serves as a prostitute. Sal dies in the childbirth that produces her mixed-race son, Tommy Luck, whose very presence, something like the miracle-working of Jesus, slowly transforms the camp from a den of iniquity into a blessed, utopian community. The idyll ends tragically when the toddler, Luck, clasped in the arms of a doomed miner, drowns in a flash flood that obliterates Roaring Camp.

In truth, Indian women were common fixtures in the rough, all-male mining camps of the California Gold Rush. Often forced into concubinage or prostitution, these women serviced the miners, usually in return for no more than three hots and a cot. Subtly yet remarkably, Harte transformed an Indian sex worker into a Virgin Mary for his time.

And then there is “Comanche Jack” Hamlin, a character who figures in several of Harte’s stories. Like baby Luck, Hamlin is mixed-race, a gentlemanly gambler who makes his living separating miners from their gold at the poker table. What most marks the gambler’s heritage, in Harte’s words, is his “Indian stoicism—said to be an inheritance from his maternal ancestor.” Based on a fabled gambler of legendary existence known as Cherokee Bob, Comanche Jack comes across as Harte imagined himself—clean, well-dressed, watchful, suave and well-mannered, a man of wits profiting from brutes. Harte’s depiction of the enviable character as part-Indian likely resulted from how the Tuluwat massacre had changed the writer’s perception.

As for the Thugs, they evaded any legal reckoning. Under California law at the time, no Indian could testify against a white man. With Harte’s judicious self-exile as the most obvious example of what could happen to anyone who protested the murders, no other community members had the temerity to testify against the Thugs. A grand jury convened to investigate the matter shut down after just four days, claiming—falsely—the killers could not be identified. The case was closed, and the Thugs roamed free to continue their Indian-killing ways.

Larrabee, the bloodthirsty leader of the malefactors, soon abandoned Humboldt County for the 1862 Salmon River gold rush in what would become Idaho, hoping to find the pot of gold that had escaped him in California. He didn’t find it there, either.

The Wiyots, of course, had the worst time of it. Soldiers stationed at Fort Humboldt, south of Eureka near Bucksport, rounded up the survivors, purportedly for their protection, and later transported them far north to the Klamath River Indian Reservation at Fort Ter-Waw. Conditions there were appalling—marked by starvation rations, epidemics, forced labor and indentured servitude—all made worse by a devastating flood that wiped out the fort and reservation in 1862. By then the Wiyot population—which in precontact years, according to tribal oral tradition, had numbered some 2,000 members—had collapsed to just 200. By 1910, only 100 were left.

The Wiyots, however, have demonstrated a gritty resilience, and today the tribal nation, centered on the Table Bluff Indian Reservation on the south shore of Humboldt Bay, numbers some 600 members. In 2000, the tribe purchased the 1.5-acre former site of Tuluwat on Indian Island, which for more than a century had been used as a shipyard, its grounds contaminated by various paints, solvents and other chemicals. In 2004, the city of Eureka ceded 40 acres of the island back to the tribe, and in 2006, it turned over another 60 acres. With the waste cleaned up and the village site partly restored, the Wiyots celebrated their annual World Renewal Ceremony in 2014, ending a hiatus of 154 years. Slowly, through the Wiyots’ ritual intervention, the cosmos is being returned to its original and rightful balance. WW

Author-poet Robert Aquinas McNally is based in Concord, Calif. His most recent nonfiction book is The Modoc War: A Story of Genocide at the Dawn of America’s Gilded Age, which received a 2018 California Book Awards gold medal from the Commonwealth Club of California. For further reading he recommends Bret Harte, by Gary Scharnhorst; An American Genocide, by Benjamin Madley; and Murder State, by Brendan C. Lindsay.