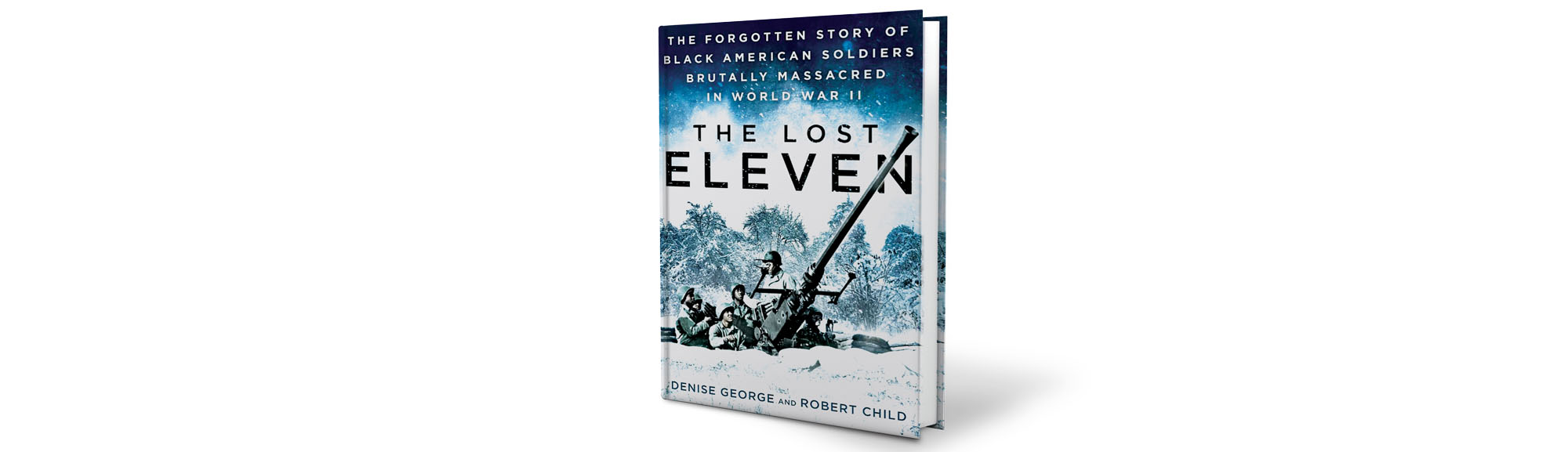

THE LOST ELEVEN CHRONICLES THE TERRIBLE FATE OF 11 SOLDIERS of the 333rd Field Artillery Battalion, an all-black army unit. It was a story unfamiliar to me—something that didn’t come as a surprise. As a history professor specializing in African American military history, I know that black soldiers have historically served the nation with distinction and honor, but with very little vcognition or appreciation. This story reflects one more example of that.

A caution, though: the book’s introduction reveals that The Lost Eleven is historical fiction with “created dialogue and unrecorded history” along with real wartime facts. And it refers to its historical figures as “characters”—an unusual reference for a work of history. This may not be problematic for some readers, but those with a serious interest in history will find themselves wondering what is real and what is imagined from page to page.

The book begins with a climactic scene in which a German assault in the Ardennes Forest of Belgium overwhelms the 11 GIs, who frantically retreat. The two-and-a-half-page chapter then quickly jettisons back in time eight years to Berlin, where Adolf Hitler debates whether to host the 1936 Olympic games. The next chapter takes readers, in three pages, to Bessemer, Alabama, and the home of future GI George Davis. Then comes another two-page chapter, on Hitler’s decision to invade Eastern Europe.

This back-and-forth format may make readers feel as though they are watching a movie with multiple storylines, plots, and main characters. On looking further into the 333rd Field Artillery Battalion, I discovered that The Lost Eleven is based on a 70-minute movie of the same name, written and directed by coauthor Robert Child, which perhaps explains the book’s unusual format.

Despite the timeline-hopping, I enjoyed several aspects of the book. The authors devote a great deal of attention to the military campaigns of Adolf Hitler and his generals from 1936 until the end of the war in Europe. Unfortunately, the book focuses more on that than it does its main subjects: the 11 black soldiers whom German forces brutally murdered in Wereth, Belgium, on December 17, 1944. Tipped off by villagers, the army’s 99th Division discovered their frozen mutilated bodies in a cow pasture almost two months later.

Though the army documented the incident and removed the bodies for proper burial, the final 1949 Congressional Report on War Crimes—which included similar atrocities by Nazi troops—omitted mention of the massacre. No official reason for this was given, leaving one to wonder whether it was an oversight or intentional due to racism. For the next 50 years, the military failed to acknowledge the gruesome deaths of the men, and their nation remained unaware of their sacrifice. For all its faults, The Lost Eleven succeeds in finally giving the 11 due recognition.

I wish there were more books that highlight the sacrifice, patriotism, and heroism of African American soldiers during America’s conflicts at home and abroad. It is a growing field of history that has much to teach us about America’s past and present. —Marcus S. Cox serves as Associate Dean of Graduate Programs and Professor of History at Xavier University of Louisiana.

This review was originally published in the October 2017 issue of World War II magazine. Subscribe here.