A growing library of pilot biographies and unit histories preserves details of World War II for posterity.

In the wake of six years of 50th anniversaries, there seems to be a revived effort to record the memories of World War II participants for posterity. The lives of many noteworthy individuals in military aviation are being documented in book form, while those with shorter stories to tell are often being compiled within the common context of squadron histories.

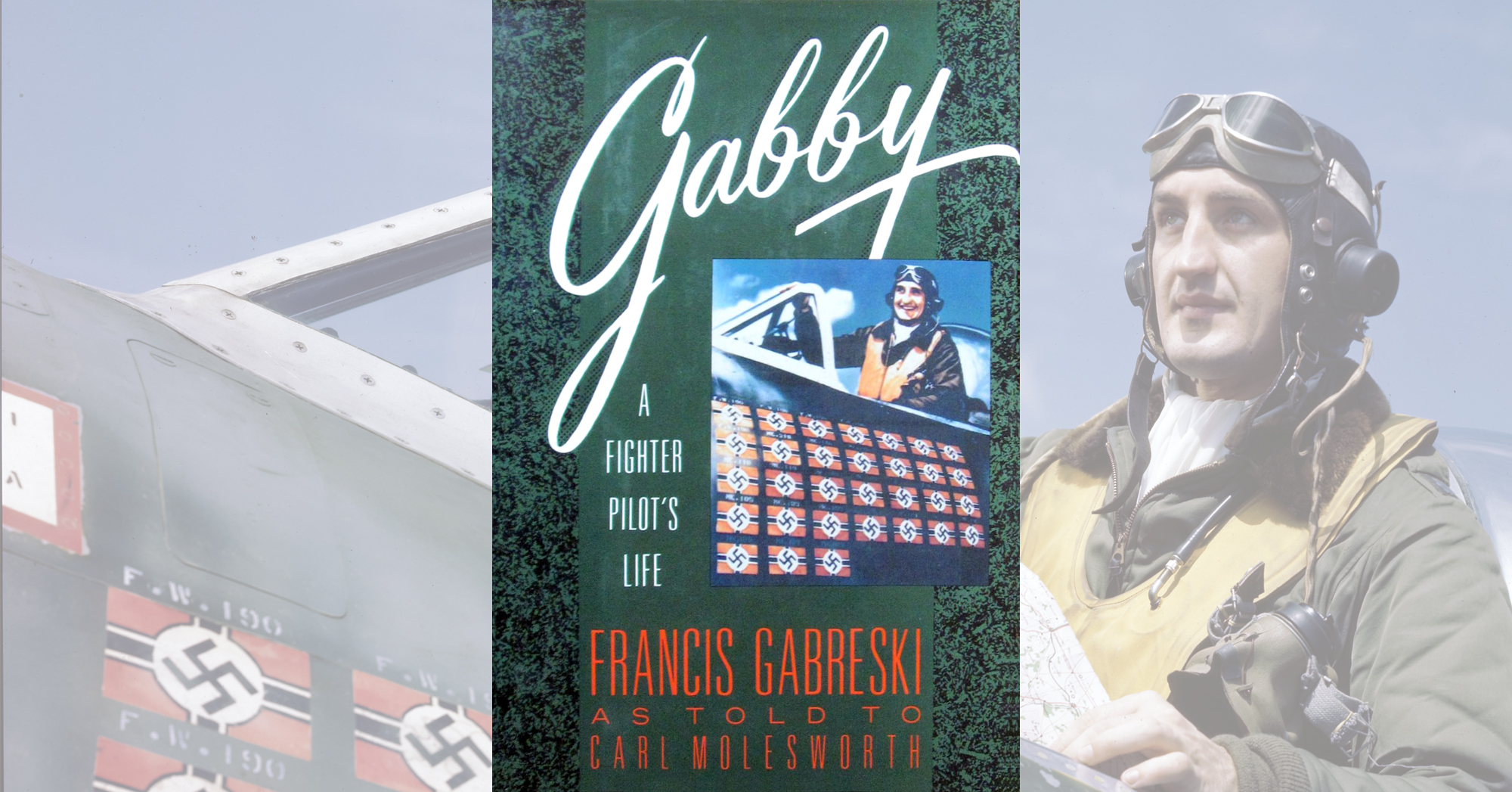

Schiffer Military History has been publishing an expanding line of books documenting both individuals and units in the past several years, and the latest four to come off its prolific press are outstanding examples of both genres. One is an autobiography, Gabby: A Fighter Pilot’s Life, by Francis Gabreski as told to Carl Molesworth (Schiffer Publishing, Ltd., Atglen, Pa., 1998, $45). That Francis S. “Gabby” Gabreski was the leading American ace in the European Theater of Operations is common knowledge among historians of World War II. Somewhat less well-known is the fact that Gabreski flew North American F-86 Sabre jets during the Korean War, adding six enemy planes to the 28 he had downed in the previous conflict.

Gabreski had dropped out of Notre Dame University to join the U.S. Army Air Corps in 1940 and got his first assignment, the 45th Squadron of the 15th Pursuit Group, operating Curtiss P-40s from Wheeler Field, Hawaii. As he went to wash and shave on the morning of December 7, 1941, the sound of low-flying aircraft, explosions and machine-gun fire drew him to the window.

“Just then a gray monoplane roared past the barracks,” he recalled. “I could see its fixed landing gear and the red circles it carried for insignia. And the gunner sitting behind the pilot was firing away for all he was worth. I stood there in shock for a second until the truth hit me. That was a Japanese aircraft. We were under attack!”

Gabreski went on to fly Supermarine Spitfires with the Poles of No. 315 Squadron, Royal Air Force, and distinguish himself flying Republic P-47D Thunderbolts in Major Hubert S. Zemke‘s famed 56th Fighter Group of the Eighth Air Force. He accidentally mushed his plane into the ground during a strafing attack on July 20, 1944, and spent the rest of the war as a German prisoner.

Aided by aviation historian Carl Molesworth, Gabreski presents a detailed and comprehensive yet lively account of his eventful life and times, accompanied by a visual feast of photographs and color profiles of the aircraft he flew during both World War II and Korea. As both a pilot’s view of aerial combat and a revealing character study of its protagonist, Gabby is a model for the way a fighter pilot’s autobiography should be.

Similar in format is Schiffer’s reprint of an old classic, Happy Jack’s Go Buggy: A Fighter Pilot’s Story, by Jack Ilfrey with Mark Copeland (1998, $35), originally written in 1946. The title of this firsthand account by the 1st Fighter Group’s first ace refers to the name Ilfrey applied to the nose of his Lockheed P-38 Lightnings and later his North American P-51D Mustang. After narrowly escaping internment in Portugal during a ferry flight from Britain to Morocco, Ilfrey downed five German aircraft with the 1st Fighter Group over North Africa and added three more while serving in the Eighth Air Force’s 20th Fighter Group–including a Messerschmitt Me-109G that collided with his P-38J. Then, like Gabreski, Ilfrey went down–his P-38 fatally struck by anti-aircraft fire from a train he was strafing on June 11, 1944–but, unlike Gabreski, Ilfrey managed to make his way back to Allied lines with a little help from some French friends.

After writing down his experiences while they were still fresh in his mind, Ilfrey set the manuscript aside, completed his education, and, as he put it, went “from a hell-raising fighter pilot to a conservative banker” and got “completely away from everything pertaining to W.W.II and almost every one I had known during those days.” He finally published the manuscript in 1978 and began hearing from old squadron mates and aviation historians. In 1982, he started editing the 20th Fighter Group’s newsletter, King’s Cliffe Remembered (a reference to their base in England), and in the process he noted, “I learned many things that I had forgotten and many other facts that I did not know when I wrote the first manuscript in 1946.”

Although it is based on the original text and retains the original foreword by Edward V. Rickenbacker–the leading ace of the original 1st Pursuit Group during World War I–Schiffer’s version of Happy Jack’s Go Buggy incorporates new and updated information as well as a wealth of photographs.

Both the unit and the individuals who comprised it are given ample coverage in Schiffer’s The Skull & Crossbones Squadron: VF-17 in World War II, by Lee Cook (1998, $45), which documents the exploits of the first U.S. Navy fighter squadron equipped with the Vought F4U-1 Corsair. Originally, VF-17 was to have operated from the aircraft carrier Bunker Hill, but when the Corsair was judged unsuitable for use on carrier decks, the unit joined Marine squadrons that had already been using the new fighter with great success from island bases in the Solomons.

Between VF-17’s first combat on November 1, 1943, and the end of its second tour of duty in March 1944, the unit was credited with 152 Japanese aircraft shot down for the loss of 20 aircraft and 12 pilots in action. VF-17 produced 15 aces, the highest scoring of whom was Ira C. Kepford, with 16 victories. Although the beards and casual attire of Lt. Cmdr. J.T. Blackburn’s squadron earned them notoriety as “Blackburn’s Irregulars,” VF-17 fought first and foremost as a team in the air. The key to its success was summed up by former pilot William L. Landreth: “One of the things one has to look out for in the fighter business is the tendency for people to want to take center stage and forget about who is supporting, and it’s much more effective if the squadron or division or section of 2 aircraft as a minimum, worked as a team rather than have one person as the star.”

The Skull & Crossbones Squadron ably reflects that philosophy. Author Lee Cook’s detailed mission-by-mission study is supplemented by short biographies of all of VF-17’s personnel, as well as a wealth of photographs, paintings and even a short epilogue on recent reunions of the surviving members.

Another excellent comprehensive unit history in Schiffer’s growing library is Any Place, Any Time, Anywhere: The 1st Air Commandos in World War II, by R.D. van Wagner (1998, $39.95). The 1st Air Commando Group was a unique composite unit, combining fighters, bombers and transports to support British and American forces in the China-Burma-India theater. Led by Lt. Cols. John R. Allison and Philip G. Cochran–the model for Flip Corkin in Milton Caniff’s comic strip Terry and the Pirates–the commandos provided supplies and air evacuation for Colonel Orde C. Wingate’s Chindits, as well as vital air support for the British defenders during the decisive battles of Imphal and Kohima in April 1944. It was also the first group in the U.S. Army Air Forces to employ a helicopter, the Sikorsky YR-4, under combat conditions.

Unlike some of his fellow squadron chroniclers, van Wagner extended his research to the enemy side. He presents testimony from the Japanese that confirms the magnitude of the air commandos’ contribution to Allied victory in Burma. He also demonstrates how the activities of this overlooked outfit laid the groundwork for special air operations in later wars, including the Vietnam conflict.

Yet another recent squadron history comes from a different publisher. Like the 1st Air Commando book, In a Now Forgotten Sky: The 31st Fighter Group in WW2, by Dennis C. Kucera (Flying Machines Press, Stratford, Conn., 1997, $49.95), presents a detailed chronicle of an unusual unit that fought over a lesser-known theater of operations–in this instance, the Mediterranean Theater of Operations (MTO). In a case of reverse Lend-Lease, the pilots of the 31st Fighter Group initially flew Supermarine Spitfires from Britain and later North Africa. The 31st subsequently flew North American P-51 Mustangs in the Fifteenth Air Force, scoring the most aerial victories (5701-2) and producing the leading ace (John J. Voll, with 21) in the MTO.

Although he combines a meticulous presentation of facts with lively human-interest vignettes that evoke the spirit of the era, author Dennis C. Kucera overlooked one golden opportunity when he prepared his book. The 31st Group fought a remarkable variety of enemies as it escorted bombers over targets such as Budapest, Bucharest and Sofia. Yet the author does nothing to shed more light on opposing aircraft, which the Americans believed were all German. Such perceptions were understandable at the time, but in fact the 31st often clashed with Romanian, Hungarian and Bulgarian as well as German fighters. There is a strong possibility, for example, that Mustangs of the 31st Group killed third-ranking Hungarian ace László Molnár (25 victories) on August 7, 1944, and top-ranking Romanian ace Alexandru Serbanescu (45 victories) on August 18.

The author at least mentions the incident following Romania’s switch to the Allied side on August 24, 1944, in which Romanian ace Contantin Cantacuzino (erroneously referred to as Carl in the book) flew a Messerschmitt Me-109G to Foggia with newly freed prisoner of war Lt. Col. James A. Gunn III stuffed in the radio compartment. It was two Mustangs of the 31st that subsequently escorted Cantacuzino back to Bucharest, to arrange for the air evacuation of Allied POWs from Romania.

It will be up to other researchers to investigate the Axis side of the 31st’s combats over Eastern Europe in greater detail–for which task In a Now Forgotten Sky can be a helpful tool. A postscript on the group’s postwar history and color profiles of 10 Spitfires and eight Mustangs round out another useful addition to aviation historians’ libraries.