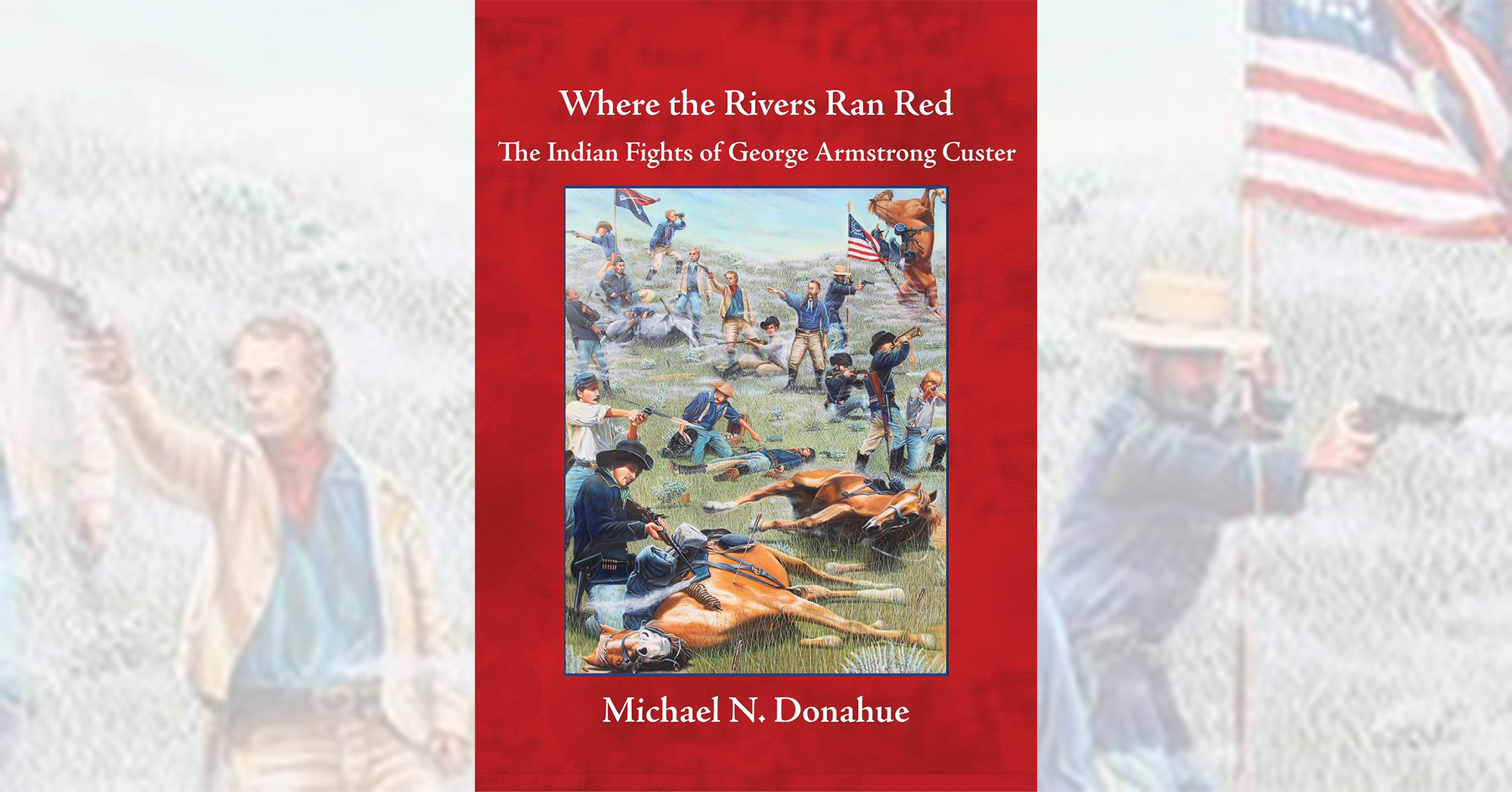

Where the Rivers Ran Red: The Indian Fights of George Armstrong Custer, by Michael N. Donahue, San Juan Publishing, Montrose, Colo., 2018, $59.95

Many have attempted to record George Armstrong Custer’s Indian fights, particularly the Battle of the Little Bighorn, and the results have been mixed. Thus, this well-written, well-researched endeavor is most welcome. By experience and training Michael Donahue is uniquely qualified to examine Custer’s record in the Indian wars. His 30-plus years as a seasonal ranger at Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument (LBBNM) make him as knowledgeable as anyone about the history of the battle and the landscape that played such a vital role in Custer’s Last Stand. “One of the most interesting aspects of my job as a park ranger at the battlefield is having the opportunity to physically check out what one can and cannot see or hear due to terrain and distance,” he writes. “There is no substitute for good in-the-field investigation, which is lacking in much of the research on the battle.”

Donahue not only studied the park’s extensive archives and artifacts but also consulted important unpublished primary sources. Avoiding ponderous analyses of Custer’s orders and other technical matters, the author relates the story of Custer in the West in an interesting, informative way. Complementing the text are Donahue’s reader-friendly maps and high-resolution digital images from the LBBNM collection and elsewhere.

Particularly commendable is Donahue’s emphasis on the impact of Custer’s previous Indian fights on the outcome of the Battle of the Little Bighorn, particularly on the lessons he learned, miscalculated or even ignored. Capturing noncombatants as hostages at his Nov. 27, 1868, fight on the Washita River in Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma) set a tactical precedent for the June 1876 Little Bighorn fight. Custer’s 1873 experiences on the Yellowstone River in Montana Territory bred overconfidence, as he’d used bold maneuvers over favorable terrain there, and his outnumbered troops successfully fought Lakota and Cheyenne warriors armed with repeating rifles. Such skirmishes, the author writes, “reinforced Custer’s negative opinion of the fighting abilities of the tribesman.” On the Little Bighorn three years later Custer again faced a superior number of warriors armed with repeating rifles, but the landscape was unfavorable, and the enemy was far more aggressive, due to their strategic victory over Brig. Gen. George Crook at the Rosebud a week earlier and because they had more at stake. “The village noncombatants at Little Bighorn would be in immediate danger,” Donahue concludes, “and the warriors would fight with a ferocity that Custer would never have witnessed during his limited Indian fighting and hostage-taking career.”

In appendices the author addresses technical questions that might otherwise annoy or distract the reader if incorporated in the narrative. He also devotes space to a battle timeline, takes issue with inflexible time/motion studies that have resulted in major interpretive errors and stresses that by horseback is the only realistic way to estimate travel times. “I believe in using general relative estimates,” he writes, “since no one can prove without a doubt what happened every minute, and to do so is an effort in futility.” He suggests that Custer’s attack at Medicine Tail Ford on the river came about 10 minutes after the start of Major Marcus Reno’s valley fight.

—C. Lee Noyes