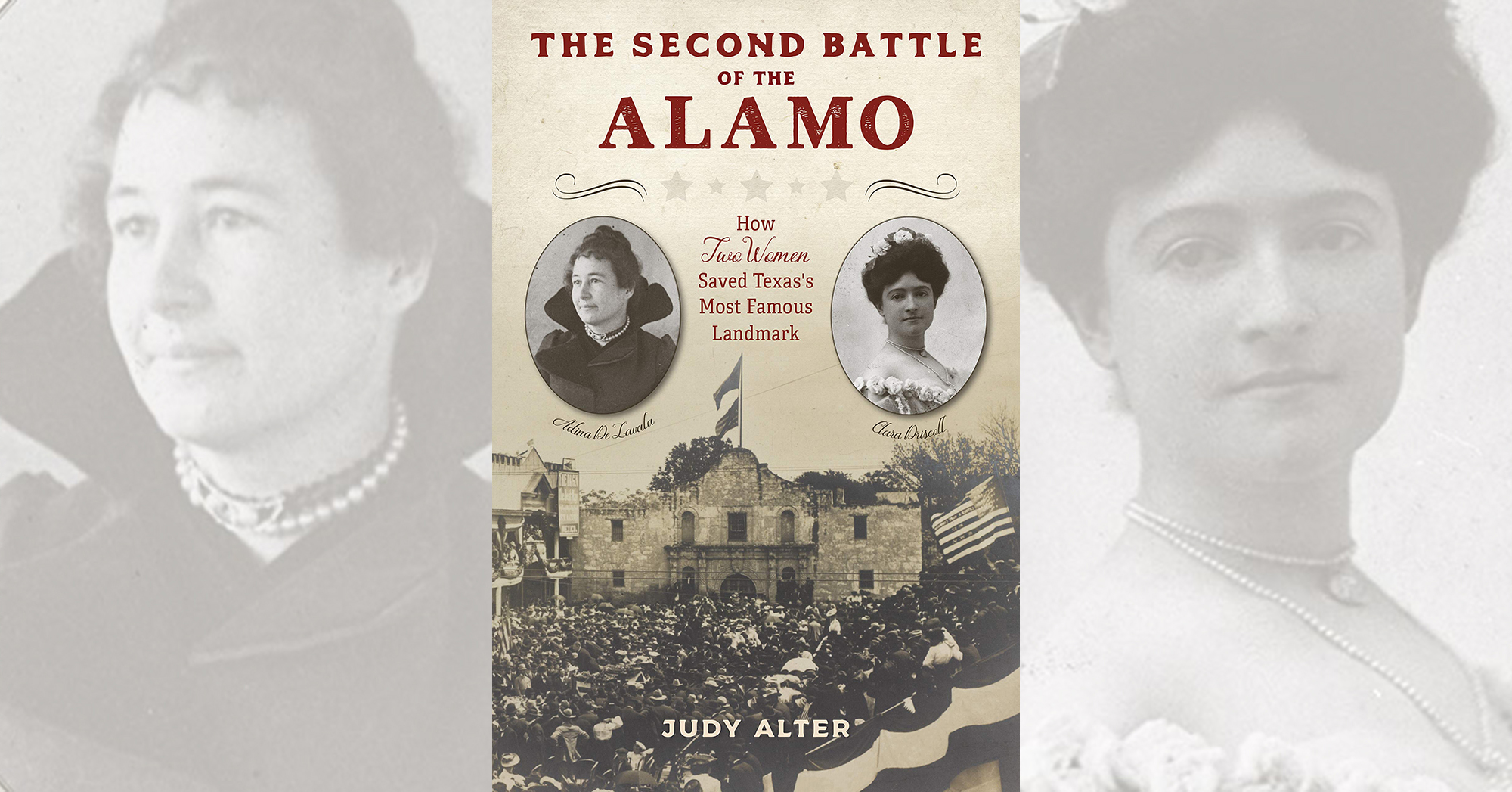

The Second Battle of the Alamo: How Two Women Saved Texas’ Most Famous Landmark, by Judy Alter, TwoDot, Helena, Mont., and Guilford, Conn., 2020, $22.95

Adina Emilia De Zavala and Clara Driscoll, two strong-willed Texans, are credited with having saved the San Antonio site of the 1836 Battle of the Alamo. A pioneering preservationist, De Zavala (1861–1955) was determined that Texans and other Americans not only remember the Alamo but also see it in good standing. Ranch heiress and philanthropist Driscoll (1881–1945) was equally committed to its preservation. The two saw eye to eye at first (Judy Alter’s first chapter is called “An Unlikely Alliance”), but then had a personal fight—the second Battle of the Alamo. “A different outcome to the second battle might not have changed the history of Texas much,” the author writes, “but it would have robbed Texas and the United States of an icon, a symbol of the rich history of Texas.”

De Zavala—the granddaughter of Lorenzo De Zavala, who had signed the Texas Declaration of Independence and been elected first vice president of the Republic of Texas—organized a group of history-minded Texas women dubbed the De Zavala Daughters. In 1893 they became a chapter of the larger Daughters of the Republic of Texas (DRT). Her immediate goal was to save the Alamo’s long barrack, a central site of the fighting, from development. In the early 20th century she sought out Driscoll to help raise funding—private at first and then from the state Legislature. Unlike De Zavala, however, Driscoll wanted to tear down the barrack to make room for a remembrance garden centered on the chapel. Who had custody of the Alamo site became the principal bone of contention, and it pitted the De Zavala contingent against Driscoll’s supporters in the DRT. The DRT ultimately won custody, and Driscoll offered to pay for the demolition of the long barrack. In desperate defiance De Zavala “stormed the gates” to barricade herself in the old building. “Reporters,” writes Alter, “played up her belief that the actual battle took place in the long barrack, not the chapel, and she won the nation’s sympathy for her determination to preserve the truth.” Thanks to De Zavala’s dogged efforts, the restored long barrack today houses a museum.

Yet to much of the public Driscoll remains the “Savior of the Alamo.” She did use some of her own money, but the state reimbursed her, and while she was mainly interested in the chapel itself, it was her down payment that saved the long barrack. It is ironic, the author notes, that the state-owned chapel—the building that remains the public symbol of the 1836 battle—was not what Clara saved; rather it was the long barrack, the building she wanted to destroy. Still, in no small part to urban sprawl, De Zavala would not recognize the Alamo site in 2020. “Today,” writes Alter, “the plaza stands almost as the compromise the two women never reached in life, fulfilling parts of each of their visions.” Alter’s last chapter is called “The Twenty-First Century and a Third Battle of the Alamo.” It might take another book to cover that “battle.”

—Editor

This post contains affiliate links. If you buy something through our site, we might earn a commission.