Growing up in Saigon, Vietnam, from 1959 to 1962, I always felt watched over. In photographic portraits, President Ngo Dinh Diem, in his ice cream suit, was everywhere, from the main Post Office to my neighborhood bicycle shop. No matter what venue, graffiti never marred his benevolent black-and-white presence.

Nor did the president’s photo change, despite upheaval wrenching Diem’s nascent republic, bruised and battered by centuries of forced occupiers: Chinese, Khmer, Japanese, French, and American.

Diem in his photograph wore a solemn, faraway look, as if he could see a future that was not going to be pretty. He held himself like a true mandarin ruler—placid and imperturbable, beyond time and human circumstance. He seemed more medieval than contemporary; a devout Catholic, he likely modeled himself on France’s St. Louis IX, the Crusader King.

My family, also Catholic, lived near the Presidential Palace, so I considered President Diem a neighbor—a neighbor who during my stay across the street had survived two attempted coup d’états.

In one incident, paratroops from Diem’s own army besieged his palace; I saw a soldier shot dead in the park in front of my house. In the other uprising, a pilot from Diem’s air force bombed the presidential residence, extensively damaging the palace—and my home.

I thought of President Diem as a survivor, but I worried that he lived in a bubble. Years later my mother, Barbara Colby, described our former neighbor as “aloof; detached; as if he was not really aware of the threat facing the Vietnamese people.”

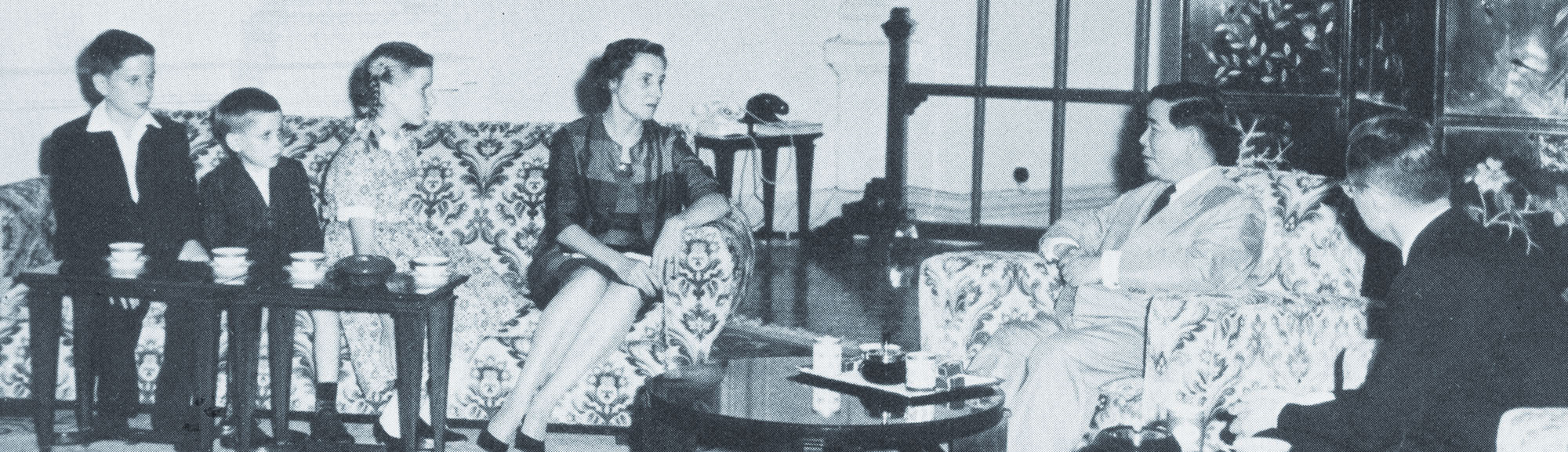

In May 1962, about to leave Vietnam, my family visited the Presidential Palace for a farewell tea. No handlers or interpreters or reporters attended. We chatted in French, seemingly for hours, as if Diem had all the time in the world. We did not.

My father, William E. Colby, had been the Central Intelligence Agency station chief in Saigon—he worked with Diem and Diem’s brother-in-law, Ngo Dinh Nhu, on the Strategic Hamlet program, meant to disrupt Viet Cong hegemony in rural areas (and did so successfully, North Vietnamese General Vo Nguyen Giap admitted much later). This was only one of several goodbyes my father had to get to.

I thought, who could be more important to say goodbye to than President Diem?

In Lost Mandate, Geoffrey Shaw brings that lost world back to bitter life as he indicts American hubris, specifically that of senior policymakers in the U.S. State Department and White House acting on behalf of President John F. Kennedy, who tacitly approved the undertaking of an American-backed military coup against the president of the Republic of Vietnam. That overthrow resulted in the brutal murder of Diem and Nhu on the outskirts of Saigon 20 days before Kennedy himself was slain halfway around the world in Dallas, Texas.

Shaw’s harrowing account chronicles the multiple ways in which diplomats W. Averill Harriman, Henry Cabot Lodge, Roger Hilsman, and Michael Forrestal colossally mismanaged and undermined a staunch ally whom the United States had wholeheartedly supported in the mid-1950s as a bulwark against Communist expansion in Southeast Asia.

Liberally employing primary sources, the author presents a stream of direct quotes and footnotes that in many ways reveal more than his text does—a device that might undermine other such histories but only strengthens this one.

In Shaw’s relentless narrative, the Kennedy administration’s blithe insistence that Diem, who was fighting a war, reform his government and embrace liberal democratic ideals unravels telegram by telegram and memo by memo. The reader comes to feel revulsion at the petulant anti-Diem cabal in the U.S. State Department, whose members thought they knew best how to govern Vietnam and win the war.

It was as if the Americans were deliberately feeding Diem to the wolves, convinced that a coup would work and that a cadre of South Vietnamese generals could run a weak, shaky nation threatened inside its borders by thousands of Viet Cong guerrillas and from without by divisions of highly motivated, well-armed North Vietnamese regulars.

The American press played a shocking role. Bent on delegitimizing Diem and making names for themselves, Neil Sheehan, David Halberstam, and Peter Arnett gunned to get the “inside story” on a leader they labeled a “dictator” and a war they preordained as a debacle.

In Shaw’s estimation, Diem and Nhu had champions: Frederick Nolting, the steadfast U.S. ambassador to Vietnam, and my father, who went on to become the CIA’s chief of the Far East. Nolting and Colby supported the two almost to a fault, always realistic as to whom the United States should want running a fledgling republic at war—a mandarin who had his people’s respect or an unelected junta of ruthless military commanders.

After the assassination of Diem and Nhu, my father said, “South Vietnam never got back on track.”

I remember my mother asking, “How did this happen, Bill?”

“I was against it,” he answered. “We never thought that this would happen.”

Of Diem, President Lyndon B. Johnson said simply, “We killed him. We all got together and got a goddam bunch of thugs and we went in and assassinated him.”

To use a phrase of my father’s, Lost Mandate is a “shocker.” Shaw has extracted verbatim a deadly accurate litany of shame from State Department and White House memos and telegrams, a portrait of American betrayal that set in motion a war that would cost more than 58,000 Americans and millions of Vietnamese their lives—a war Lost Mandate proves need not have happened.

—Carl Colby directed, produced, and wrote the documentary The Man Nobody Knew: In Search of My Father, CIA Spymaster William Colby. He is writing a memoir. His website is carlcolbyfilms.com

This review was originally published in the September/October 2016 issue of American History magazine. Subscribe here.