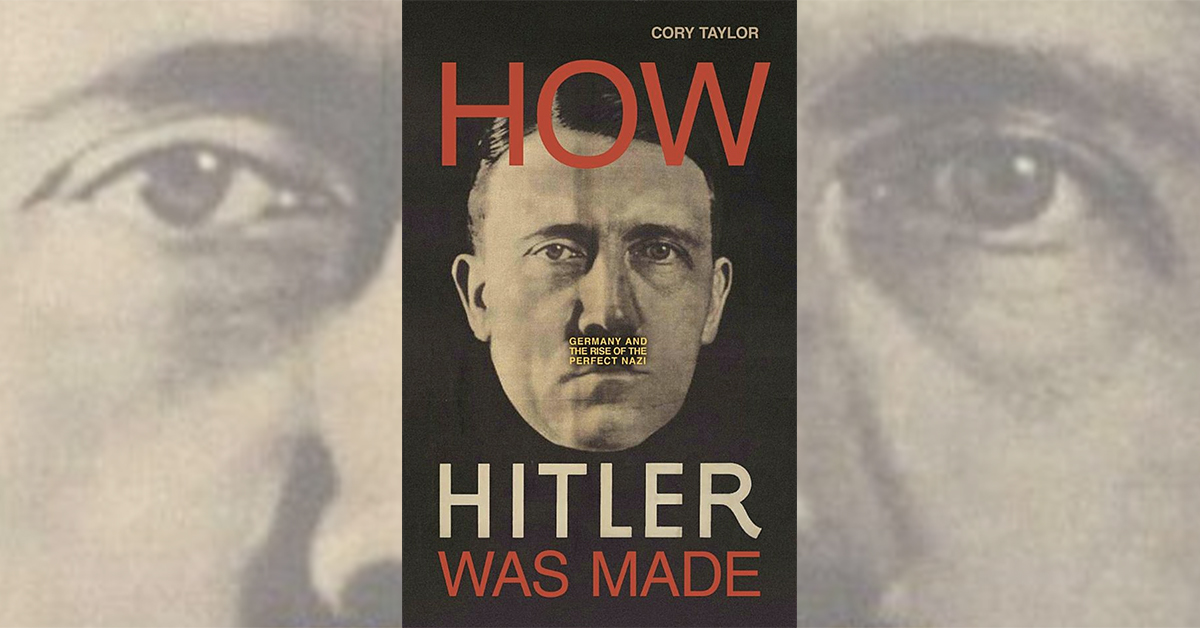

How Hitler Was Made: Germany and the Rise of the Perfect Nazi, by Cory Taylor, Prometheus Books, Amherst, N.Y., 2018, $25

Biographies of Adolf Hitler remain a major industry, but comprehensive volumes are best reserved for superstar historians. This is award-winning documentary filmmaker Cory Taylor’s first effort, and he wisely limits himself to the years up to 1924, when Hitler rose to national prominence. The result is a lively, insightful history of post–World War I German politics, which were only modestly less gruesome than what followed when the Führer took power.

Hitler was eking out a living as an artist in Munich when the war broke out in 1914. Already a fierce German nationalist, he promptly enlisted, serving in a mildly dangerous position as runner for a regimental headquarters. After the Armistice he returned to Munich but remained in the army, as he needed the income.

In the turmoil of 1918 leftists in Munich proclaimed a socialist republic. Until right-wing forces overthrew it in May 1919, Hitler served—seemingly without objection—in a unit supporting the republic and then continued to serve the government that replaced it. In July superiors assigned him to military intelligence.

Sent to investigate the German Workers’ Party, whose name belied its tiny membership, Hitler was drawn to its militantly nationalist, anti-communist and anti-Semitic views and distrust of the national government. He joined the party (as its 55th member), and his dazzling oratory drew attention. Membership grew. In 1920 it became the National Socialist German Workers’ Party, and the next year Hitler demanded absolute power as its leader.

By 1922 he was a local celebrity. As he advocated violent overthrow of the Weimar government, he was not especially popular with Munich’s establishment, although he had admirers, including the chief of police. The 1923 Beer Hall Putsch was his idea, and though it flopped, the subsequent trial attracted national attention. Aided by a sympathetic judge, he passed himself off as a war hero fighting an evil government to restore German self-respect. Though convicted, he served nine months in a comfortable prison during which he wrote his autobiography and Nazi treatise, Mein Kampf, swore off violent overthrow and resolved to seek power by democratic means. As Taylor points out, that was a no-brainer, as by the mid-1920s the German economy had improved and the Weimar government was reasonably stable.

All of this is well-trod ground, and Taylor is not a professional historian, so he relies largely on secondary sources (including the 2017 book Becoming Hitler, by Thomas Weber). That said, he writes well about a man whose atrocities remain without parallel but whose campaign promises to restore national glory to a people humiliated by despicable foreigners and traitorous bureaucrats has been revived by leaders around the world with dramatic success.

—Mike Oppenheim