Ever since Charles Darwin published his Origin of the Species, archaeologists have been obsessed with discovering the “missing link”–that hypothetical species representing the transition between ape and human. Whether or not the remains of such a creature have been found, or ever will be found, is still a matter of debate.

Technological development is also an evolutionary process. The transition between one era and another can sometimes be symbolized by the introduction of a single product. In that sense, Boeing’s P-26 Peashooter embodied the transition from the highly maneuverable, stick-and-wire fighter biplanes of World War I to the fast, all-metal monoplane fighters of World War II.

Boeing’s P-26 was a milestone in three respects. It was the first U.S. Army Air Corps fighter to incorporate several important design features that would become standard on aircraft subsequently used in World War II. To placate conservative elements in the Air Corps, however, the P-26’s designers were constrained to include several anachronistic features in the airplane that hampered its development potential. The Peashooter was also to be the last fighter aircraft mass-produced by Boeing before the company went on to bigger things, in both the figurative and the literal sense.

The company that would later become Boeing Aviation was founded in 1916 by William Edward Boeing. He was a prominent Seattle businessman who found little difficulty in making a transition of his own, from the lumber business to speedboat building to seaplane construction. Considering the company’s long-standing reputation for building large aircraft, it is often forgotten that Boeing was ever in the fighter business. During the 1920s, however, the Seattle-based company was in close competition with its eastern rival, Curtiss, for a dominant place in the American fighter arsenal.

Boeing’s first large aviation contract, secured in 1919, was for the construction of 200 Thomas-Morse MB-3 fighters for the U.S. Army Air Service. Known as the MB-3A, Boeing’s version incorporated a number of improvements over the Thomas-Morse original, including redesigned tail surfaces, improved radiators and a welded steel-tube fuselage in place of the original’s wooden structure. As a result of the quality of the MB-3A, Boeing went on to become one of the giants of the aviation industry while Thomas-Morse faded into obscurity.

Boeing’s next fighter project, the Model 15, was an original design employing a steel-tube fuselage, wooden wings and a 435-hp Curtiss D-12 liquid-cooled engine. Submitted in direct competition with a design from the much larger Curtiss Company, Boeing took a big chance on the new fighter by building the prototype airframe at the company’s own expense. The gamble paid off when the Army awarded Boeing a contract for 30 production versions in 1923, which they called the PW-9 (pursuit, water-cooled). The Navy also bought 14 examples under the designation FB-1 (fighter, Boeing). The Model 15 was the first in an unbroken series of production Boeing fighters that would culminate in the P-26.

Boeing biplane fighter development reached its pinnacle with the introduction of the Model 83 in 1928. Constructed of bolted aluminum instead of welded steel, the Model 83 was more compact than its predecessors. Powered by a 450-hp Pratt and Whitney Wasp air-cooled radial engine, it was a great success. The Model 83 was ordered over the next five years in successively improved models, designated for the Army as the P-12 and for the Navy as the F4B.

Despite the success of the Model 83, Boeing’s management was convinced that the days of the biplane were numbered. Boeing began investigating the possibility of a monoplane fighter in 1928. This resulted in the appearance of three prototype monoplanes in 1930. The first two, built as a private venture, were little more than parasol-winged derivatives of the Model 83. One was demonstrated to the Army as the XP-15. The other, a similar airplane equipped with a tail hook, was delivered to the Navy as the XF5B-1. Both proved to be faster than the equivalent Boeing biplane, but both were rejected because their rate of climb and maneuverability were inferior to the Model 83.

The third monoplane fighter prototype, the XP-9, appeared later in 1930. It was a more radical design built to meet an Army specification. Powered by a 600-hp Curtiss water-cooled engine, the XP-9 was a shoulder-wing monoplane with an aluminum monocoque fuselage. The plane’s top speed of 213 mph was much faster than either of the parasol-winged prototypes or the production Model 83. However, the cockpit was located just aft of the strut-braced wings, severely restricting the pilot’s view. The design was also criticized for poor control characteristics. The Army preferred to stay with the P-12, which was a proven winner.

The appearance of yet another Boeing monoplane prototype in 1930, the Model 200 Monomail, was of far greater significance. Designed as a high-speed mail plane, the Monomail’s development was a result of Boeing’s experience in the airline business during the 1920s. Boeing Air Transport, as the airline subsidiary was known, later became the basis for today’s United Airlines.

The Monomail was a cantilevered, low-winged monoplane with an aluminum monocoque fuselage and retractable landing gear. The plane was 41 feet long, had a span of 59 feet, and could fly 600 miles with a payload of 2,300 pounds of mail or passengers. The top speed of the sleek Monomail, a modest 158 mph, was restricted only by the relatively low power of its single 525-hp Pratt and Whitney Hornet radial engine. The Monomail was the true progenitor of the unbroken line of highly successful Boeing airliners leading up to today’s Model 777.

In 1931, Boeing developed a twin-engine bomber for the Air Corps based on the design of the Monomail, called the B-9. It would be the first of a long line of illustrious Boeing bombers. With a top speed of 186 mph, the B-9 rendered Boeing’s own P-12/F4B biplane fighters virtually obsolete.

It was also in 1931 that Boeing’s designers began work on a new monoplane fighter that the company designated the Model 248 and that was initially known to the Air Corps as the P-936. First flown on March 20, 1932, the new fighter was an all-metal, low-wing monoplane with an aluminum monocoque fuselage, somewhat reminiscent of a scaled-down Monomail. However, the similarities ended there. Like the earlier PW-9, the three P-936 prototypes were funded by Boeing, with only the engine and instruments being supplied by the Air Corps.

The Boeing Company was in the business of selling aircraft at a profit, not wasting money on futuristic but unwanted prototypes. It therefore took a conservative approach in the design of its new fighter in the hope that the aircraft would prove more readily acceptable to the Army Air Corps.

Aviation experts of that period were dubious about the value of a retractable landing gear. It was widely believed that any reduction in drag would be offset by the added weight of the retraction mechanism. The early retractable landing gears, which were manually operated, were also notoriously prone to malfunction. The new Boeing fighter was therefore designed with a fixed landing gear in streamlined fairings.

The Air Corps was convinced that a cantilevered wing would not stand up to the stresses imposed by the violent maneuvers of a fighter. Consequently, the Model 248’s wings had external wire bracing not unlike that on the monoplane fighters of World War I. Many pilots of the early 1930s also considered good visibility to be one of a fighter plane’s most important characteristics. Before the advent of airborne radar, the pilot who survived was often the one who saw his opponent first. Aircraft radio was still in its infancy, thus communications between pilots were often carried out by visual signals.

Enclosed canopies were felt to be confining, and some of the early versions often caused optical distortion. Moreover, many pilots simply preferred the feeling of flying in the open. Consequently, despite the expectation of speeds well in excess of 200 mph, the Boeing fighter was designed with an open cockpit.

In spite of those concessions to the conservative elements in the Air Corps, the P-936 was regarded as a radical design. It looked as if it belonged at the Cleveland Air Races rather than on an Army fighter field. Its clean lines and short wings gave it a high speed, but at a price in ease of handling not all Air Corps officials were willing to pay. Although they were built in only three months, the three prototypes were extensively tested throughout the remaining eight months of 1932 before the decision was finally made to order the monoplane into production as the P-26. In the meantime, the Army hedged its bets by ordering 25 P-12F biplane fighters from Boeing.

The P-12F and the P-26 were both powered by the same 600-hp Pratt and Whitney Wasp air-cooled radial engine, and their performance characteristics make an interesting comparison. The top speed of the P-26 was 234 mph–20 percent faster than the P-12F. It also had a range of 375 miles, 75 miles farther than that of the biplane. Because of its lower wing loading, however, the P-12F’s climb rate of 2,920 feet per minute was 24 percent greater than that of the monoplane. Also, the P-12F’s service ceiling of 31,400 feet was 4,000 feet higher than that of the P-26.

Most alarming to the Air Corps was the P-26’s landing speed of 82 mph, 17 mph faster than the P-12F. That was considered too fast for the average service pilots of the day. The narrow-tracked main landing gear added to concerns about a serious danger of landing accidents. The Army requested Boeing to design a set of landing flaps that were retrofitted to all P-26 airframes. The flaps, the first ever installed on a production U.S. Army Air Corps aircraft, reduced the plane’s landing speed to a more acceptable 73 mph.

The Boeing management must have realized that, even with the new flaps, the P-26’s stall speed would have been unacceptable for use on a carrier deck. Unlike with its previous fighter designs, Boeing did not offer a version of the P-26 to the Navy. The Navy did not accept any monoplane fighters at all until 1939, when the Brewster F2A Buffalo entered service.

Another alteration to the design resulted from a fatal accident involving one of the P-26 prototypes. The airplane flipped over onto its back while landing, breaking the test pilot’s neck. The upper wing of the biplanes had provided a measure of protection under these circumstances, but the P-26’s low-wing design left the pilot vulnerable to serious injury. Hence, the pilot’s headrest was raised an additional eight inches on production models and was internally reinforced like the roll bar on a racing car. The new headrest gave the P-26 a humpbacked appearance that remains one of the airplane’s most distinctive features.

The P-26 was finally ordered into production in January 1933. Despite its obvious advancements over its predecessors, its appearance was not universally welcomed. The unofficial name “Peashooter,” supposedly inspired by the blast tubes of its two internally mounted machine guns, was not initially a complimentary one. Many pilots, accustomed to the superior handling of the earlier biplanes, were less than pleased with some of the flying characteristics of the new monoplane.

The Air Corps bought a total of 139 Peashooters between 1933 and 1934, including the three original prototypes. The majority were P-26As of the initial production batch, of which 111 were built. The next 25, designated P-26Bs, were to have been equipped with a fuel-injected version of the Wasp engine that promised to improve the plane’s performance at higher altitudes, but only three of the new engines were initially available. The remaining 22 airframes were completed as P-26Cs, designed to accept the fuel-injected engine but equipped with the carbureted engine of the P-26A. As more fuel-injected engines became available, some of the P-26Cs were subsequently upgraded to P-26Bs.

The Peashooter was 23 feet 7 inches long, and its wing spanned 28 feet. The fighter weighed 2,271 pounds empty and just over 3,000 pounds loaded. It was armed with two synchronized machine guns in the floor of the cockpit, either two .30 calibers or one .30 and one .50 caliber. The plane also could carry up to 200 pounds of bombs in a rack under the fuselage. The Peashooter appeared at the height of the Depression, when the various branches of the military were competing for the limited funds available from the government. Many people still did not take military aviation seriously, and the Army Air Corps was anxious to show off its capabilities in the hope of gaining public support for expanding the service. As a result, the mid-1930s became arguably the most colorful period in American aviation history.

The standard finish applied to Army aircraft included chrome-yellow wings and tail and a blue fuselage. The rudder was painted with a blue vertical stripe on the leading edge and 13 horizontal alternating red and white stripes on the trailing edge. There were also colored stripes on the wings and fuselage, denoting the individual aircraft’s position in its flight, squadron and group. In addition, squadrons and groups added their own dazzling markings to their planes. Aircraft in many of the regular service squadrons during the 1930s were decorated more elaborately than any military aircraft since, with the possible exception of those operated by special aerobatic units. Particularly flamboyant were the P-26s flown by the 17th Pursuit Group at March Field in Southern California, which consisted of the 34th, 73rd and 95th Pursuit squadrons. The 34th Pursuit Squadron members were the original “Thunderbirds,” and their P-26s bore that famous insignia 13 years before the U.S. Air Force was created.

Paleontologist Stephan Jay Gould has made the case that evolution does not proceed at a steady rate, but happens in fits and starts. The P-26 provides an illustration of that theory. The Peashooter had the misfortune to be introduced into service at the beginning of one of the most explosive periods of development in the history of aviation technology. Boeing’s monoplane fighter, which was regarded as advanced in 1933, appeared outmoded next to the Martin B-10 bomber, (introduced in 1934) with its enclosed cockpits, retractable landing gear and 212-mph top speed. Compared to the Seversky P-35 and Curtiss P-36 fighters that appeared in 1936, and corresponding foreign designs such as the Hawker Hurricane and Messerschmitt Bf-109, the Peashooter seemed a whole generation out of date.

The P-26, considered radical at the time of its introduction, had become obsolete within three years. The very features that Boeing had designed into the fighter to placate a then-conservative Army Air Corps staff had doomed it to rapid extinction.

Boeing produced an improved version of the Peashooter, called the P-29, during 1934. It featured a fully cantilevered wing, a retractable landing gear and an enclosed canopy. Despite those improvements, the airplane only managed to achieve a top speed of 240 mph. The Air Corps regarded the YP-29, as the preproduction evaluation model was called, to be only a marginal improvement over the P-26, and not worth disrupting the production program. Boeing was becoming involved in the development of much larger types of aircraft by that time. The YP-29 was the last fighter the company built for the Army.

The introduction of the far more advanced Seversky P-35 caused the Peashooters to be displaced from Stateside fighter units. By 1938, they were only operational with fighter squadrons at remote overseas bases in Panama, Hawaii and the Philippines. The rest were relegated to the advanced training role, preparing pilots to fly the next generation of fighters.

While the production lines were turning out P-26s for the Air Corps, Boeing contracted to supply a batch of similar fighters to the Nationalist Chinese government. A total of 10 Peashooters, designated Model 281 by Boeing and Model 248 by the Chinese, were built for the Chinese in 1934. The company did not deliver the airplanes until 1936, however, because of funding problems.

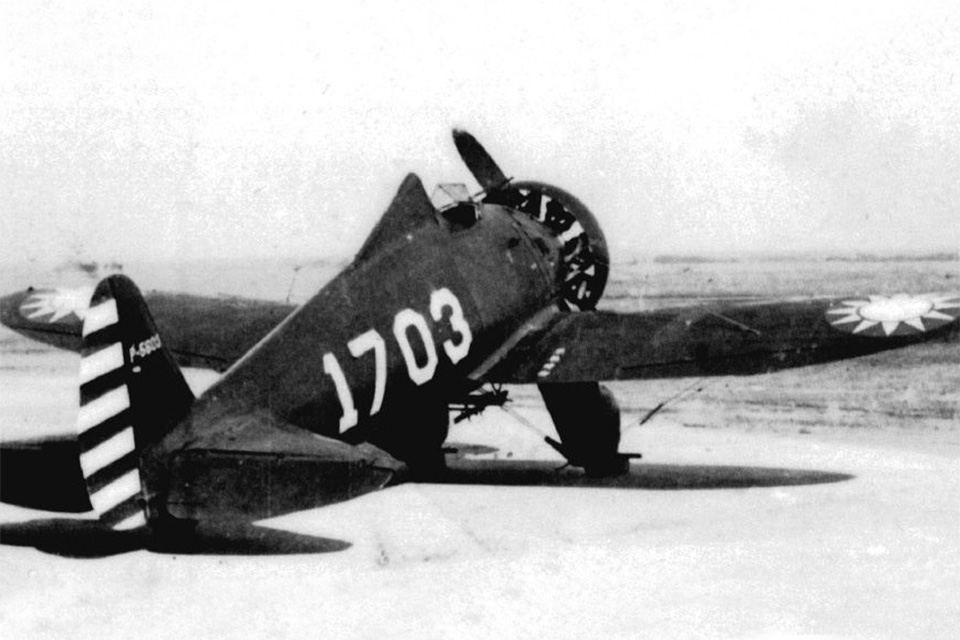

The Boeings were delivered to the 17th Squadron, commanded by Wong Pan-Yang, a Sino-American volunteer from Seattle, in time to be used against Japanese aircraft over Nanking in 1937. On August 15, eight of them attacked a flight of six Mitsubishi G3M bombers and shot down all six without loss. Wong Pan-Yang in Boeing No. 1701 downed one and shared in the destruction of a second, while Los Angelesborn Wong Sun-Shui in plane No. 1703 accounted for a third. The rig-ors of combat and primitive operating conditions took a heavy toll on the Boeing fighters, though, and by the end of 1937 none of them remained operational. The 17th was re-equipped with Gloster Gladiator biplanes, in which Wong Pan-Yang would bring his total score to five. Wong Sun-Shui was credited with 8.5 victories before being mortally wounded in action on March 14, 1941.

One additional Model 281 was sold to Spain in 1935 for evaluation as a possible successor to the Nieuport-Delage NiD-52 fighter that was then the backbone of the Spanish air service. Delivered to Barajas, in Madrid, without armament on March 10, 1935, the Boeing fighter was test-flown by Boeing and Spanish military pilots. Boeing’s asking price of 500,000 pesetas per plane ultimately resulted in the Spanish government’s decision to reject the 281 and instead obtain a license from the British Hawker Aircraft Company for Hispano Suiza to produce 50 Hawker Spanish Fury biplane fighters.

The Boeing 281 was still at Barajas when the Spanish Civil War broke out on July 18, 1936, and was hastily armed with two .303 Vickers machine guns under the wings for front-line service with the Republican forces. Operating from Getafe airfield, it saw considerable action against the fascist rebels, on one occasion flying in formation with a Spanish Fury, four Dewoitine D.372s, two Loire 46s and two Nieuport-Delage NiD-52s.

Republican air strength at Getafe was down to one Fury, one Dewoitine and the Boeing 281 by mid-October 1936. Then, on October 21, Ramón Puparelli, one of the Boeing fighter’s original test pilots, took it up to defend the airfield against three enemy Fiat CR.32s, only to be shot down. Puparelli managed to bail out. Some time later, the Spanish Republican government, which had never actually bought the prototype, finally paid $20,000 to Boeing representative Wilbur Johnson, through its embassy in Paris, for the 281’s use in combat.

By the end of 1941, when the United States became involved in World War II, the P-26 was considered a flying antique. The last operational Peashooters in the Philippines had been replaced by P-35As during the summer of 1941. The 12 remaining Boeing fighters were transferred to the 6th Pursuit Squadron of the Philippine Army Air Corps at Batangas Airfield on Luzon.

Captain Jesus A. Villamor led the P-26As of the 6th Pursuit Squadron, the only ones of their type to see action in World War II, and they were flown with great courage by their Filipino pilots. On December 12, 1941, Villamor brought down a Mitsubishi G3M2 of the 1st Kokutai over Batangas. Lieutenant Jose Kare even managed to shoot down a Mitsubishi A6M2 Zero with his obsolete Boeing on December 23. Generally, however, pitted against overwhelming numbers of superior enemy aircraft, the Peashooters proved as ineffectual as their name implied. The last surviving Filipino P-26s were burned on Christmas Eve to prevent their falling into enemy hands.

The P-26 was also retained in service in the Panama Canal Zone for coastal patrol duty after Pearl Harbor, until more modern aircraft could be spared from more active theaters. The last 11 aircraft were transferred to the Panamanian government, which sold them to Guatemala in 1943. The Peashooters served in the Guatemalan air force until they were replaced by surplus North American P-51 Mustangs in 1950. The last of the ex-Guatemalan P-26s was restored to its colorful prewar Army Air Corps markings and is now on display in the National Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C.

Boeing’s P-26 Peashooter represented a technological milestone in the history of American air power, brief though its moment in history was. Hailed as the world’s fastest radial-engine fighter when it entered service, it was quickly rendered obsolete by the very changes that it introduced. Today, it remains the epitome of the 1930s era of aerial art deco.

A longtime aviation enthusiast, Robert Guttman is an officer in the U.S. merchant marine. For further reading: The American Fighter, by Enzo Angelucci with Peter Bowers; and Aircraft of the Spanish Civil War, 1936-1939, by Gerald Howson.

Boeing’s Trailblazing P-26 Peashooter was originally published in the July 1996 issue of Aviation History Magazine. Subscribe here!