Facts, information and articles about Battle Of Waterloo, an event of the Napoleonic Wars

Battle Of Waterloo Facts

Dates

June 18, 1815

Location

Mont St. Jean near Waterloo, Belgium

Generals/Commanders

Napoleon Bonaparte, France

Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington, Anglo-Dutch

Gebhard von Blucher, Prussia

Soldiers Engaged

72,000 France

68,000 Anglo-Dutch

48,000 Prussian

Outcome

French Defeat

Result

Ended both the career of Napoleon and the Napoleonic Wars.

Battle of Waterloo summary: The Battle of Waterloo in Belgium (June 18, 1815) was the climactic battle that permanently ended the Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) and wrote finis to the spectacular career of Napoleon Bonaparte, Emperor of France. Opposing his French army were the troops of an Anglo-Dutch force (Great Britain and allied nations—The Netherlands, Belgium, and the German state of Hanover) under the command of Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington, and a Prussian army led by Field Marshal Prince Gebhard von Blücher. The battle began around noon and ended that evening with Napoleon’s army in retreat. So significant was the defeat of the “God of War” Napoleon that ever since when a seemingly unstoppable individual, force or movement is defeated, it is said to have “met its Waterloo.”

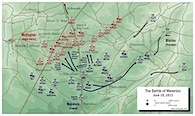

The battlefield was actually south of the village of Waterloo, near Mont St. Jean, with its center running north-south along the Charleroi-Brussels road. Wellington’s dispatches were sent from Waterloo, and so that name was given to the battle by the British. The French call the event the Battle of Mont St. Jean. Blücher favored calling it the battle of “La Belle Alliance,” the name of a farmhouse where Napoleon had his headquarters and where the British and Prussian commanders met following the battle. La Belle Alliance could be taken to refer to the multinational alliance that defeated the French Emperor, but the farm’s name, which predated the battle, is said to have originated with a “belle alliance” between the mistress of the house and one of her farmhands following the death of her second husband.

The French force consisted of roughly 72,000 men, including 48,000 infantry, 11,000 cavalry, and 250 guns. Another 33,000 men under the command of Marshal Emmanuel Grouchy were at Wavre, south of Waterloo, and did not take part in the battle.

The Anglo-Dutch army (British, Dutch, Belgian, and Hanoverian troops) led by the Duke of Wellington, had approximately 67,000 men—about 50,000 infantry, 11,000 cavalry and the crews for 150 guns. The Prussians under Blücher saw approximately 48,000 of their men and 135 guns engaged.

Napoleon’s Dreams of Empire

Born August 15, 1769, to a gentry family on the island of Corsica, Napoleon attended a military school in France and joined the artillery service at the age of 16. His strategic skills, personal bravery and political connections allowed him to rise quickly to the rank of general in the tumultuous period of the French Revolution, 1789–1799. On Nov. 9, 1799, he was named “First Consul” of France and consecrated as emperor on December 2, 1804.

Beginning with the Battle of Montenotte in Italy (April 12, 1796) in which he defeated an Allied Austrian-Piedmontese Army, Napoleon established his reputation as a great strategist and commander through a series of campaigns that planted the French flag throughout most of Europe and parts of North Africa and the Mideast. Though he sometimes suffered setbacks and defeats, he became the most feared man in Europe, time and again winning battles against the odds. After he lost much of his Grande Armee on the desolate steppes of Russia in 1812, the French were gradually forced back by a coalition of European armies. On April 6, 1814, Napoleon abdicated and was exiled to live out his life under guard on the island of Elba off Italy.

Napoleon Returns from Exile

La Petit Empereur was not yet ready to relinquish his dreams of conquest, however. On February 26, 1815, he escaped from Elba and returned to France where he remained popular, and soon he was building a new army, but it was not the army that had won great victories in the past. On paper, he had perhaps 200,000 soldiers in March 1815, but over 30,000 were on furlough and some 85,000 had deserted. There were not enough muskets to arm all the men. At least 500,000 projectiles were needed for the artillery. Shoes, uniforms, horses, harness—the list of shortages went on and on.

Perhaps most critical among those shortages were sufficient numbers of skilled military commanders at the highest levels. Few of Napoleon’s trusted corps commanders remained. Men who had only commanded divisions were placed over corps, but in these elevated positions they had not yet earned the respect of the men in the ranks. The French Army’s formerly high morale sagged.

His old adversaries, on the other hand, now stood united in their determination to prevent Napoleon—and France’s revolutionary anti-monarchy ideas—from threatening the old monarchies of Europe. Austria, Prussia, Russia, and Great Britain united against him, with 450,000 troops they could bring to battle relatively quickly; potentially, they could deploy 700,000 in two month, all backed up by British gold for weapons, ammunition and other logistical concerns.

Napoleon realized he could not hope to defeat such a force once its scattered elements coalesced. He decided to strike swiftly into Belgium, break lines of communication between the British and allied troops commanded by Arthur Wellseley, Duke of Wellington (who had performed admirably against French troops in Spain) and the Prussian Army under Field Marshal Prince Gebhard Leberecht von Wahlstatt Blücher. Unfortunately for the French military genius, these two commanders probably understood, appreciated and supported each other more than the leaders of any other coalition armies. Wellington said, “I am inclined to believe that Blücher and I are so well united, and so strong, that the enemy cannot do us much mischief.”

Battles that Preceded Waterloo

Operating under tight secrecy, Napoleon assembled his force, the Army of the North, in the area of Maubeuge in early June. Deserters warned his opponents that he planned to strike through Belgium toward The Netherlands, but both British and Prussian headquarters remained unconcerned about an immediate attack. Deserters from the French army included a corps chief of staff and a division commander, further exacerbating its command problems.

Napoleon’s plan was to seize Brussels and sever the Nivelles-Namur highway, which provided the only lateral road the British and Prussians could use to unite. He sent his left wing—”not much less than 45 or 50,000 men,” Napoleon wrote—under the command of Marshal Michel Ney toward the village of Quatre Bras. Ney had commanded VI Corps in earlier campaigns was named commander of the left wing on June 13, five days before the Battle of Waterloo.

The right wing, of the same size as the left, was placed under Marshal Emmanuel Grouchy, who had repeatedly proven his courage in battle and his devotion to Napoleon, but he had never before had a command so many troops. Neither Ney nor Grouchy advanced with the alacrity Napoleon needed from them.

In addition to the two wings of his army, Napoleon held back the Imperial Guard, elite troops of his old Grande Armee, as a reserve to commit as he saw fit.

The French got a hard-won victory against the Prussians at Ligny, inflicting twice as many casualties as they suffered. Blücher was injured leading a cavalry charge, but his chief of staff, General August W. A. Gneisenau, took over and boldly ordered the corps commanders to march northward toward Tilly—bringing them closer to Wellington’s force—instead of east to Liege. The French failed to pursue rapidly, and both Napoleon and Grouchy could share the blame for that. Inadequate information made Napoleon overly cautious the day after the fight, and his orders to Grouchy to pursue the Prussians would play a significant role in the defeat at Waterloo.

While the French and Prussians were going at each other around Ligny, approximately two miles (3.2 km) away at the tiny crossroads village of Quatre Bras Marshal Ney waited until 2:00 in the afternoon to attack. Had he attacked in the morning, he would have faced only the 2nd Dutch-Belgian Infantry Division and enjoyed a 6-to-1 advantage. (The Dutch-Belgian commander was Baron H.G. de Perponcher-Seinitzky, one of Napoleon’s former commanders.) About an hour after the battle began, Allied reinforcements began arriving. Ney’s I Corps under General J. B. D’Erlon received an order—it is uncertain from whom—to march to Ligny to support the French there. When Ney learned of their departure, he sent orders demanding the corps return; it did but dispatched a portion of its infantry and cavalry to Ligny. The entire corps could have been a decisive factor at either Ligny or Quatre Bras, but spent much of the day marching between the two battles.

After dark, the Allied force withdrew from the fields and woods around Quatre Bras. It had taken approximately 4,800 casualties; Ney suffered 4,300.

At both Ligny and Quatre Bras, the French lost the chance to inflict a telling blow on the Allies on June 16. The stage was set for the bloodbath near Waterloo.

The Battle of Waterloo, June 18, 1815

On the afternoon of June 17, heavy rains began and continued into the night, but the morning of Sunday, June 18, arrived sunny and clear. On the rolling plateaus to the south of Waterloo, near Mont St. Jean, the French (some 72,000 strong) and Anglo-Dutch (68,000) armies were encamped some 1,500 yards apart. In this area the land masks hollows and ravines where forces could be hidden until an enemy is close enough to be confronted by troops that seemed to rise from the very earth before them. It was land well suited to the tactics the Duke of Wellington had perfected in Spain.

He placed his reserves and part of his main force behind the slopes of the plateau he had chosen to make his stand on; they would be concealed from view and largely protected from artillery. To the west, forward of his right flank, he dispatched troops to the Chateau de Groumont (Hougomont). It was a brick-and-stone redoubt, fully enclosed and further protected by ditches, an orchard and hedges. Directly to his front he sent another force to a similar mini-fortress, La Haye Sainte. No similar fortifications existed on his left, or eastern flank, though there were smaller strongholds scattered about. This was the direction from which the Prussians would be arriving to reinforce Wellington’s Anglo-Dutch force, so he was less concerned about his left.

Napoleon’s favored tactic was envelopment, swinging around his enemy’s flanks, but the heavy rains had left the low ground muddy between the plateau where his forces awaited their orders and the plateau where the Anglo-Dutch had their line. The mud would slow his cavalry and artillery in any envelopment attempt. He chose, therefore, to make a direct attack on Wellington’s center. The mud also caused him to delay his main attack from 9:00 a.m. to noon, to allow the ground more time to dry.

He ordered General H. C. M. J. Reille to make an attack in the direction of Groumont (Hougomont). It was intended to be a limited, supporting attack launched a half-hour before the main effort, but the commander of Reille’s lead division, after driving the enemy from some woods around the chateau, decided to assault the chateau itself. Both sides reinforced, and the fight drew in nearly half of Reille’s corps in a battle for a position of questionable value to the French; Napoleon had not ordered that it be taken.

South of where the fighting was taking place, Grouchy had been ordered to seize Wavre and block the Prussians, but he moved slowly, and two corps had already passed through the town by the time his Frenchmen arrived. However, the same mud that had caused Napoleon to favor a direct assault over an enveloping maneuver also slowed the Prussian march to reinforce the Anglo-Dutch at Waterloo. Blücher, bruised and aching from his horse falling on him during the charge at Quatre Bras, urged his men on with the plea, “Forward, lads! I have promised my brother Wellington. You don’t want to cause me to break my promise, do you?”

Wellington, as the day wore on, was muttering, “Give me Blücher or give me night.”

Knowing that the two enemy forces would soon unite, Napoleon faced the choice of withdrawing to fight another day on ground of his choosi ng, or commit the rest of his force and hope to break Wellington’s line before Blücher’s full force arrived. Weighing against a retreat was the knowledge that an army of 250,000 Austrians were advancing toward Paris, and Napoleon felt that retreating would cost him support of the French people. He chose to decide the issue there, on the rolling plateaus around Mont St. Jean, south of Waterloo.

ng, or commit the rest of his force and hope to break Wellington’s line before Blücher’s full force arrived. Weighing against a retreat was the knowledge that an army of 250,000 Austrians were advancing toward Paris, and Napoleon felt that retreating would cost him support of the French people. He chose to decide the issue there, on the rolling plateaus around Mont St. Jean, south of Waterloo.

For a half-hour he bombarded his enemy with 80 guns, but because Wellington had positioned much of his force on the downside of slopes away from the French artillery, the bombardment’s effect was diminished.

D’Erlon’s I Corps, which had spent most of June 16 marching and countermarching between the fights at Ligny and Quatre Bras, now slogged through wet cornfields that crowded their columns together. A Belgian brigade near the strongpoint of La Haye Sainte fled, and D’Erlon’s men came on until British infantry at a hedge-lined road staggered them with a volley, and a cavalry attack drove the French soldiers back.

Wellington reinforced La Haye Sainte. Around 4:00 p.m. both sides began heavy artillery bombardments. By this time, Wellington’s center began to disintegrate under the repeated French attacks and started to fall back. Marshal Ney, believing the Anglo-Dutch line was faltering, ordered a cavalry attack unsupported by infantry or artillery. The horsemen thundered forward, the ground shaking beneath the hooves of their mounts, crested a hill, and were greeted by British infantry formed in a patchwork of squares, the most effective defensive formation against cavalry. The French swept around the squares, trying to find a way to penetrate them, but momentum was broken. A counterattack by British cavalry drove the Frenchmen back, but reinforced, they came on again. Four times they charged, and four times they were repulsed.

By 6:00 La Haye Sainte had fallen at last; Reille’s men had Groumont (Hougomont) more or less surrounded, and a powerful attack against Wellington’s center might have broken through, but the Prussians had begun arriving around 4:00 and threatened the French rear by assaulting Plancenoit, a sizeable village with a stone church and stone-walled cemetery that could serve as strongpoints for either side. Napoleon directed the corps of the Count of Lobau, reinforced by two battalions of the Guard, in a counterattack that gradually forced the Prussians back, but the counterattack had taken 10,000 French away from the central battle area, where they could have been used to break through Wellington’s weakened center.

Had Grouchy not followed the letter of his orders and marched to the sound of the guns, as some of his subordinates encouraged him to do, Blücher’s men would have been caught between two strong forces, and that could have swung the day’s advantage to Napoleon. Grouchy, however, was not a particularly imaginative commander, and existing military practices weighed in favor of staying where he had been ordered to go, so he spent the afternoon confronting less than 20,000 men of the Prussian III Corps around Wavre with his 30,000-plus force.

While Napoleon’s attention was focused on the Prussian threat to his rear, the impulsive, hot-headed Ney took command of the rest of the Guard—some of the finest infantry in the world at the time—and led them in a futile attack against the strongest point of Wellington’s line. Finally, the French right flank caved, taking any remaining hope that Napoleon could avoid defeat on this day marked by mud, incomplete information, indecision, and impetuous orders that threw away French lives to little or no advantage.

Still, Napoleon remained calm. He ordered what was left of the Old Guard to form squares across the road south of La Haye Sainte while he withdrew his battered army. Even when the Guard ran out of ammunition, they held to their posts as their beloved emperor had commanded.

Aftermath of the Battle of Waterloo

Back in Paris, Napoleon abdicated for the second time. When his attempt to escape to America was thwarted, he threw himself on the mercy of the British, who got him out of France aboard one of their ships. He was taken to the island of St. Helena in the South Atlantic Ocean. There he remained, dictating his memoirs. After six years of exile he died in 1821, two days after receiving an extremely strong dose of calomel for symptoms that probably were due to early stages of stomach cancer, an illness that had also claimed his father and his sister, Pauline. Theories have long existed, however, that he was poisoned with arsenic. For a detailed examination of the conflicting evidence, see “Arsenic and the Emperor,” by Barbara Krajewska at Napoleon.org.

Emmanuel Grouchy fled to America but returned to France in 1821, when King Louis XVIII re-instated him with all titles but that of marshal. That title was later returned to him by Louis-Philippe, who also named him a Peer of France. Grouchy died in 1847 at the age of 80.

Michel Ney became the only French field marshal of the 1815 campaign to be executed. When Napoleon returned to France from exile Ney, in the service of the king, swore to “bring the adventurer back to Paris in an iron cage.” Instead, swayed by Napoleon’s personality and memories of their earlier victories, he chose to serve the Little Emperor. For this, he was executed by firing squad on December 7, 1815, little more than a month shy of his 46th birthday.

Von Blücher, already a highly respected combat commander though no great master of strategy or tactics, returned home from the field of Waterloo a national hero. He had been 72 and retired when Napoleon returned from exile. After the defeat of his old enemy, the Prussian marshal again retired to his estate in Silesia and continued to enjoy alcohol, tobacco and other vices for which he had always shown a great capacity until his death in 1819.

Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington, ranks among the most influential military leaders of all time, not for any innovations, but for his ability to master maneuver, artillery support, and use of terrain to display tactical and strategic genius. Nicknamed the “Iron Duke,” after Waterloo he spent 30 years in the cabinet and parliament of Britain; he became prime minister in 1828 and commander in chief of the British Army in 1842. Ten years later he died at Walmer Castle, Kent, at the age of 83. He was buried in London’s St. Paul’s Cathederal.