Facts about Battle Of Vicksburg (aka Siege Of Vicksburg), a major Civil War Battle during the American Civil War

The Battle of Vicksburg, Mississippi, also called the Siege of Vicksburg, was the culmination of a long land and naval campaign by Union forces to capture a key strategic position during the American Civil War. President Abraham Lincoln recognized the significance of the town situated on a 200-foot bluff above the Mississippi River. He said, "Vicksburg is the key, the war can never be brought to a close until that key is in our pocket." Capturing Vicksburg would sever the Trans-Mississippi Confederacy from that east of the Mississippi River and open the river to Northern traffic along its entire length.

Battle Of Vicksburg Facts

Location

Vicksburg, Mississippi. Warren County

Dates

May 18-July 4, 1863

Generals

Union: Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant

Confederate: Lt. Gen. John C. Pemberton

Soldiers Engaged

Union: 75,000

Confederate: 34,000

Important Events & Figures

Crater at the 3rd Louisiana Redan

Outcome

Union Victory

Battle Of Vicksburg Casualties

Union: 4,800

Confederate: 3,300 with nearly 30,000 captured

Battle Of Vicksburg Pictures

Battle Of Vicksburg Images, Pictures and Photos

Battle Of Vicksburg Resources

Vicksburg National Military Park

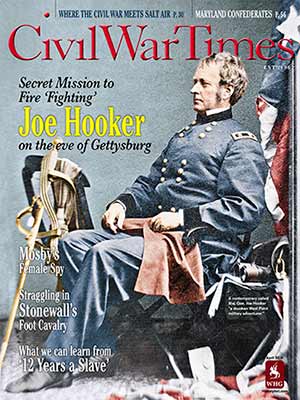

Battle Of Vicksburg Articles

Explore articles from the History Net archives about the Battle Of Vicksburg

» See all Battle Of Vicksburg Articles

First Attempts to Capture Vicksburg

The first attempt to capture Vicksburg in summer 1862 is sometimes called the First Battle of Vicksburg. It consisted of prolonged bombardment by Union naval vessels and sputtered out when the ships withdrew. At the same time, Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant was moving overland to invest the town from the rear. His advance ended when Brig. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest’s cavalry tore up his rail supply line, and Maj. Gen. Earl Van Dorn captured his supply base at Holly Springs.

Grant’s efforts to seize Vicksburg resumed in December but met repeated failures. An assault by troops of Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman’s corps against the high ground of Chickasaw Bluffs north of the town resulted in nearly 1,800 Union casualties, compared to just over 200 for the defenders. Over the coming months, Grant’s men would attempt to dig canals or find ways through the shallow, narrow bayous to bypass what is called the Confederate "Gibraltar of the West." Finally, he decided his army would have to operate south of Vicksburg, and that required the cooperation of the navy. To mask his army’s movement down the Louisiana side of the river, he had Sherman conduct two feints north of Vicksburg, and on April 17 Col. Benjamin H. Grierson left Tennessee on a cavalry raid through Mississippi that ended May 2 when he reached Baton Rouge, Louisiana. Grierson’s raid ranks among the most remarkable cavalry exploits of the war.

On April 16, 1863, a naval fleet under Rear Admiral David Dixon Porter came down the Mississippi, running the gauntlet of guns firing from the Vicksburg bluff, and rendezvoused with Grant’s Army of the Tennessee at Hard Times, Louisiana.

In the largest amphibious operation ever conducted by an American force prior to World War II, Grant and Porter transferred 24,000 men and 60 guns from the west bank to the east. They landed unopposed at Bruinsburg, Mississippi, and began marching toward Port Gibson and Grand Gulf, towns north along the river. Four divisions clashed with a Confederate brigade along Bayou Pierre near Port Gibson on May 1, costing each side between 700 and 900 men, but the two river towns were captured without further significant fighting. The rest of Grant’s army, under Sherman, then crossed the river at Grand Gulf, bringing his force to over 45,000, which he turned inland toward the Mississippi state capital, Jackson.

Grant’s Inland Campaign in Mississippi

Two Confederate forces were in the area: a small one of approximately 5,000 men at Jackson and 26,500 men of the Vicksburg garrison. Vicksburg was under the command of Lt. Gen. John C. Pemberton, a West Point-trained engineer and native Pennsylvanian with a Southern wife, who had chosen to fight for the Confederacy.

One of Grant’s advancing columns collided with a Confederate brigade at Raymond, a few miles west of Jackson, on May 12. Hours of confused fighting ended when the Southerners, under Brig. Gen. John Gregg, retreated.

The following evening, Confederate general Joseph E. Johnston arrived in Jackson. His wounding at Seven Pines, Virginia, in May of 1862 had resulted in Robert E. Lee taking over the defense of Richmond and initiating the Seven Days Battle. Johnston was now commanding the Department of the West and had been ordered to Mississippi to counter the growing threat. He looked at the inadequate defenses and ordered the troops, now about 6,000 in number, to evacuate.

The next day, Gregg’s men fought a delaying action around the town to cover the withdrawal before abandoning 17 guns and the capital to the Federals, who burned much of the town.

Johnston and Pemberton independently came to the conclusion that the best course of action was to sever Grant’s supply line to the Mississippi River. Pemberton left 9,000 men to garrison Vicksburg and marched with 17,500 to find that supply line. While trying to join with Johnston, his force encountered Grant’s marching westward, resulting in the Battle of Champion’s Hill. Overwhelming numbers carried the day, and Pemberton withdrew. One of his divisions, that of Maj. Gen. W. W. Loring, was cut off, and turned south; it joined Johnston’s forces instead of returning to Vicksburg.

The next clash came May 17 at Big Black River Bridge. Federal troops of Brig. Gen. Michael Lawler’s brigade exploited a weakness in a seemingly strong Southern position and routed their enemy. Pemberton’s weary men returned to Vicksburg, burning bridges behind them. The 20,000–25,000 he had marched out of Vicksburg with had been reduced by approximately 5,000. Including the garrison he left behind to protect the town, his effective force was not much over 30,000 men.

The Battle of Vicksburg

On May 19, Grant, hoping for a quick victory over a defeated foe, ordered Sherman’s corps to attack along the Graveyard Road northeast of town. Pemberton, the engineer, had developed a series of strong works around Vicksburg, and the Federals were repulsed by the defenders of Stockade Redan, suffering 1,000 casualties.

Three days later, coordinated assaults were made: Sherman along the Graveyard Road, Maj. Gen. James McPherson hitting the center from the Jackson Road, and Maj. Gen. John McClernand attacking from the south along the lines of the Baldwin Ferry Road and the Southern Railroad of Mississippi. Although McClernand’s men briefly penetrated what was called the Railroad Redoubt, all three columns were repulsed, with a total loss of over 3,000 men.

The Siege of Vicksburg

These losses and the strong Confederate defensive works convinced Grant to take the town by siege, cutting it off from all supply. He initiated a plan that is still studied today as a classic example of how to conduct siege warfare.

Reinforced to over 70,000 strong, for weeks his men dug trenches that zigged and zagged but steadily brought them closer to Pemberton’s positions. One group tunneled underneath the Third Louisiana Redan, named for its defenders, and on June 25 detonated barrels of black powder that blasted a hole in the works. Union soldiers surged into the breach only to be met by a counterattack. Desperate hand-to-hand fighting ensued for hours before the attackers were driven out.

A second mine was exploded on July 1 but was not followed up by an attack.

That same day, Joe Johnston finally sent a relief force from re-occupied Jackson toward Vicksburg, but it was too little, too late, and did not play a role in the fighting.

Inside Vicksburg, civilians huddled in caves to avoid the cannon shells being fired daily from Grant’s artillery around the town and the guns on the fleet in the river. Food and other supplies from outside had been cut off for a month and a half. Horses, dogs, cats, reportedly even rats became part of the diet for soldiers and civilians alike. On July 3, Pemberton rode out to discuss surrender terms with Grant. Although he had been dubbed "Unconditional Surrender" Grant after his demands to the garrison at Tennessee’s Fort Donelson the previous year, the Union commander agreed to parole Pemberton’s men. The next morning, July 4, Confederate soldiers began marching out and stacking their guns. The city of Vicksburg would not celebrate the Fourth of July as a holiday thereafter until well into the 20th century. Despite the prolonged shelling they’d endured, the Confederates’ losses during the siege had been light. Some 29,500 surrendered.

The Aftermath of Vicksburg

With the fall of the Confederate Gibraltar, the last remaining Southern stronghold on the Mississippi, Port Hudson, also capitulated. In the words of Abraham Lincoln, "The Father of Waters again goes unvexed to the sea." That same July 4, Robert E. Lee’s army was retreating toward Virginia after defeat in the Battle of Gettysburg; Helena, Arkansas, fell to Union forces; and General William S. Rosecrans forced the Confederate Army of Tennessee to withdraw from the Middle Tennessee area to Chattanooga, just north of the Georgia state line. The winds of war had shifted in favor of the North.

The Confederacy had been irretrievably divided east and west. Pemberton found the Confederate government was no longer willing to entrust him with high command and, remarkably, he resigned his commission and attempted to re-enlist as a private. Southern president Jefferson Davis commissioned him a lieutenant coronel of artillery instead.

Joseph Johnston briefly attempted to hold Jackson, but the Federals reoccupied it. Destruction there was so complete that it became known as "Chimneyville—virtually all that was left. Johnston would lead the Army of Tennessee during most of the Atlanta Campaign and again following the Southern debacle at Franklin and Nashville in the winter of 1864. He would surrender his army to Sherman near Bentonville, North Carolina, days after Robert E. Lee surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia.

Grant’s reputation as a fighter who won tough battles was cemented at Vicksburg, and by the following summer he would be in command of all Union armies in the field. He came to regret his decision to parole the Vicksburg garrison, however. Most of its men re-enlisted without being exchanged for Union prisoners, as was the custom, putting thousands more rifles back into the Southern ranks. As a result, Grant would virtually halt prisoner exchanges when he was promoted to command all armies, a decision that perhaps shortened the war but also condemned thousands of prisoners north and south to prolonged incarceration and death in the unsanitary conditions of overcrowded prisoner of war camps.

Today, the Vicksburg National Military Park stretches over 1,800 acres of fields, woods, and ravines. It includes the Vicksburg National Cemetery, the final resting place of 17,000 Union soldiers, the largest number of any national cemetery.

Banner image Tour stop 2, Illinois Monument and Shirley House from hill at intersection of Union Avenue and loop to tour stop 3, looking nw, created by William A. Faust II, Library of Congress.

Battle Of Vicksburg Articles From History Net Magazines

Vicksburg Featured Article

Account of The Battle Of Vicksburg

Originally published by America’s Civil War magazine.

Alarmed residents of Vicksburg, Mississippi, watched in despair on the night of May 17, 1863, as thousands of ragged, downcast Southern soldiers poured into their city from all directions. ‘Where are you going?’ a townsperson demanded of a fleeing Confederate. ‘We are running’ the soldier forthrightly replied.

The man the Rebels were running from, Union Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant, had ended months of Northern frustration and failure by landing an overwhelming force in western Mississippi on the night of April 30, then moving inland across the state. In 17 days of brilliant campaigning, the misleadingly phlegmatic Grant had inflicted five crushing defeats on separate bands of Confederate warriors who had always felt that enemy soldiers could never threaten them so deep on their own home soil.

All this Grant had accomplished while cut off from his base of operations and supply, and in direct violation of his stated orders to advance south into Louisiana for a combined operation against Port Hudson. By May 16, when he met and decisively defeated Lt. Gen. John Pemberton’s troops at Champion’s Hill, 25 miles east of Vicksburg, Grant stood poised for a final assault on the crucial Mississippi River town.

Vicksburg had been the object of intense Union attention since the start of the war. Abraham Lincoln knew its importance. ‘We can take all the northern ports of the Confederacy, and they can still defy us from Vicksburg’ he said. ‘It means hogs and hominy without limit, fresh troops from all the states of the far South, and a cotton country where they can raise the staple without interference.’ Confederate President Jefferson Davis called it ‘the nailhead that held the South’s two halves together.’ Though Fort Pillow to the north and New Orleans to the south were in Union hands by May 1863, Vicksburg closed the lower Mississippi to unhindered Federal traffic-and was a looming symbol of Confederate defiance.

Following his victories at Champion’s Hill and, one day later, at Big Black River Bridge, Grant was confident of quick victory. ‘I believed,’ he later wrote, ‘[the enemy] would not make much effort to hold Vicksburg.’ Sergeant Osborn Oldroyd of the 20th Ohio shared the feeling. He wrote in his diary, ‘We have now come here to compel them to surrender, and we are prepared to do it either by charge or by siege … they cannot say us nay.’

A Union charge was not long in coming. Grant, confident that one sharp push could overwhelm the demoralized Confederates in their defenses and avoid a long, uncomfortable siege, ordered an assault all along his front to begin at mid-afternoon on May 19. Major General William T. Sherman’s XV Corps was to attack points along the northern end of the’ Confederate line. Meanwhile, Maj. Gens. James McPherson’s and John McClernand’s troops were to assault the Confederate center and right, respectively.

But between the defeats at Champion’s Hill and Big Black River Bridge and the afternoon of May 19, something had happened to the Confederate Army of Vicksburg. Pemberton had left 10,000 men in the city when he ventured out, and these unbloodied troops stiffened the resolve of those returning from battle. They were also behind strong fortifications. And, as Grant soon would find out, he could not even rely on the normal competence of his corps commanders in the upcoming fight.

The May 19 action was hampered from the start. Though Grant ordered an assault all along the line, McClernand’s and McPherson’s troops were delayed by the tangled underbrush and treacherous ravines common to the area, and were pinned down by sharp Confederate rifle fire. The bulk of the assault fell, thus, to Sherman’s command.

Sherman’s advance was tentative, not the first time this was to happen at Vicksburg. Only one brigade, commanded by Colonel Giles Smith, managed to gain much headway. It advanced to the outer trenches of the ‘Stockade Redan,’ at a critical bend in the defensive lines. Troopers from the 1st Battalion, 13th U.S. Infantry, Sherman’s own pre-war unit, carried its flag to the very edge of the Rebel works.

Volunteer regiments from Indiana and Illinois joined them, but they could not enter the works because of intense Confederate fire. Other Union troops did not get as far. As one Southern officer wrote: ‘They marched up in one solid column … when [our men] opened a terrific volley of musketry. The enemy wavered a moment, and then marched forward. They were again met by another volley, when they broke and fled under cover of the hills.’

Many more Federal troops were pinned down between the lines, lying amid the canebrakes that covered the terrain. It was all they could do to remain low and avoid the killing rain of Minie bullets and artillery fire. Not long after, when night had obscured the battlefield, Sherman ordered all his advanced troops withdrawn.

This first attack was repulsed with some 950 Federal casualties, to a Confederate loss of about 250 men. True to form, Grant’s thoughts turned immediately to another attempt, this time making full use of all his command.

Historians have debated for years the wisdom of Grant’s ordering another assault. In his official report on the campaign, Grant himself gave four reasons for trying again. First, he hoped the advanced positions gained on the nineteenth would make success more certain. Also, he knew that Rebel General Joseph Johnston, to his rear, was increasing the size of his own army, which, if joined together with Pemberton’s, would outnumber Grant’s force of 45,000.

Third, a successful assault would free Grant’s men for action against Johnston and avoid the miasmal toll of a siege during a steamy Mississippi summer. Grant’s last and most important reason was his innate perception of his troops’ temperament. Even if another assault failed, he believed the men would not work as willingly on the trenches and other necessities of a siege unless they had first tried to take Vicksburg by the front door.

Here Grant was counting on the army’s confidence and swagger, built up by three weeks of brilliant success. For the most part, only Sherman’s troops had been bloodied on the nineteenth; the army still considered the Rebs demoralized and ripe for one more defeat, strong defenses or no. One observer noted, ‘They felt as if they could march straight through Vicksburg, and up to their waists in the Mississippi, without resistance.’ Observant Sergeant Oldroyd of Ohio had a clear view of the besieged city: ‘We can see the court house…with a Confederate flag floating over it. What fun it will be to take that down and hoist in its stead the old stars and stripes’

Grant planned a coordinated 10 a.m. assault. The night before, he issued full rations to his men, many of whom had spent the previous two days strengthening their positions or building roads. Perhaps he knew what lay ahead; certainly the troops did, as night stretched into morning. ‘The boys…were busy divesting themselves of watches, rings, pictures and other keepsakes’ one observer noted. ‘The instructions left with the keepsakes were varied: ‘This watch I want you to send to my father if I never return.’ ‘If I do not get back, just send these trifles home, will you?”

The attacking infantrymen were to move against the Confederate entrenchments as a solid unit–Sherman’s to the north, McPherson’s in the center on both sides of the road linking Vicksburg and Jackson, and McClernand’s to the south, centered on the Southern Mississippi Railroad track leading east out of Vicksburg.

They prepared to assault perhaps the best-defended Southern city outside Richmond. The rifle pits and trenches surrounding Vicksburg on three sides linked nine steep-walled forts, protected by ditches. Since these forts commanded high ground, they were of great advantage to the deadly marksmen wearing gray. Rebel artillerymen, in turn, had doubleloaded their cannons with grape and canister. A final obstacle faced the attackers: felled timber further choking the already rugged terrain.

During the night of May 22, Admiral David Porter’s Union gunboats opened on the city and its defenses. As dawn broke, a thundering artillery barrage from Grant’s batteries joined the bombardment, trying to soften the defenses and demoralize the defenders.

Then, shortly before 10 a.m., the firing stopped. Confederate Brig. Gen. Stephen D. Lee remembered, ‘Suddenly, there seemed to spring almost from the bowels of the earth dense masses of Federal troops, in numerous columns of attack, and with loud cheers and huzzahs, they rushed forward at a run with bayonets fixed, not firing a shot, heading for every salient along the Confederate lines:’

Major General Frank Blair’s division led the assault for Sherman’s corps on the Union right. Sherman planned to avoid the abatis-strewn gullies and hollows that had slowed his advance on the nineteenth. Blair’s troops would advance along roads in column by regiment, rather than present a broad target by marching across the difficult ground in battle line. The column would be led by a 150-man volunteer’storming party,’ carrying the boards and poles needed to bridge the ditch of the earthen fort, Stockade Redan.

Brigadier General Hugh Ewing’s brigade, the 30th, 37th and 47th Ohio and the 4th West Virginia, followed the volunteers along a dirt path, appropriately named Graveyard Road. As the storming party emerged from a cut in the road, Mississippians and Missourians in the fort opened up. Some of the advance unit made it to the earthwork itself, but aside from planting Ewing’s headquarters flag they could do little more than burrow in and wait.

Nineteen members of the storming party Sherman later called his ‘forlorn hope’ died in the assault, and 34 were wounded. The Medal of Honor later was awarded to 78 of the 150.

The 30th Ohio, close behind, got the same greeting as the volunteers. The grisly scene of death and misery that greeted the 37th Ohio a few moments later caused many in that regiment to refuse to go any further; the ensuing traffic jam meant the last two regiments had to move overland. They never made it to the fort, ending up about 150 yards east of the redan, which they fired upon with little effect. The assault by the Union right was effectively turned back. The 30th and 37th Ohio, along with the volunteer storming party, were the only units of Sherman’s to see heavy action that morning. The rest of his XV Corps, eight brigades in all, waited.

McPherson’s XVII Corps was assigned to assault the main fortifications in the center of the Rebel line, the so-called Great Redoubt and a smaller earthwork fort known as the 3rd Louisiana Redan. As with Sherman’s troops on Graveyard Road, McPherson’s men on the Jackson road eventually came under intense fire and an attack on the 3rd Louisiana Redan was beaten back.

One brigade, under Brig. Gen. John D. Stevenson, traveled overland to mount an assault on the Great Redoubt. The 81st Illinois and 7th Union Missouri regiments of his brigade, the latter largely Irish in background, took terrible losses from the Louisianans’ volleys and cannon fire, but managed to place some men in the ditch before the redoubt. The men of the 7th planted their emerald green flag on its exterior slope. However, their scaling ladders were too short and they could go no farther. They were pulled back almost immediately.

In a mere half-hour, Stevenson lost 272 officers and men. Except for one more abortive attack elsewhere on the line, this was the extent of XVII Corps action on the morning of the twenty-second.

Perhaps the hardest fighting of the morning was done along the Union left by the men of politician-soldier John McClernand’s XIII Corps. A Democratic congressman before the war who had supported Lincoln’s war effort, McClernand was not one of Grant’s favorites. He was vain and self-promoting and, though not the worst of the political generals, was at best merely competent. He also had an odd sense of timing. At one point during the fighting in Mississippi that month, he had jumped up on a stump and given his troops a political harangue, while bullets were flying.

The primary target for McClernand’s men was an earthen fort alongside the Southern Mississippi track, known to them as the Railroad Redoubt and to their foes as Fort Beauregard. It covered about a half-acre of ground, with walls 15 feet high and a ditch 10 feet wide. As with all the forts, a line of rifle pits connected it with nearby fortifications, allowing the defenders to enfilade all approaches. The 14th Division of Brig. Gen. Eugene Carr would spearhead the attack.

Precisely at 10 a.m., the men moved out. ‘Down into the abatis of felled timber and brush we went, our comrades falling thickly on all sides of us,’ wrote Lt. Col. Lysander Webb of the 77th Illinois. ‘Still up the hill we pressed, through the brambles and brush, over the dead and dying…oh! that was a half hour which may God grant we shall never be called upon to experience again.’

Joining Webb in the Railroad Redoubt action was a brigade of Iowa and Wisconsin men commanded by one of Grant’s favorite warriors, Brig. Gen. Michael Lawler. Lawler had impetuously ordered a charge at Big Black River Bridge five days earlier that, in less than five minutes, had broken the back of Rebel resistance. Now he faced an entrenched foe, the 30th and 46th Alabama regiments supported by the Texas Legion, fighting with new spirit and determination.

Starting in a ravine 150 yards from the redoubt, Lawler ordered the men to charge with bayonets fixed. Colonel William Stone led his 22nd Iowa Volunteers, mostly farmers and merchants from around Iowa City, toward the fort, with the 21st Iowa close behind in support. Regiments from Illinois and Wisconsin rushed forward near them, heading for rifle pits south of the redoubt. The Iowans reached the ditch fronting the earthwork and began crawling up its exterior slope.

Union artillery fire had opened a hole in the top of the redoubt, setting the stage for one of the most tragically heroic actions of the campaign. Sergeant Joseph Griffith of the 22nd Iowa led a group of fellow Iowans up the side of the fort and into that opening, where they fought hand-to-hand and forced most of the grayclads to abandon the works. Griffith’s men placed the colors of the 22nd on the parapet. The Confederate defenses had at last been breached, but the Union hold was tenuous. The few who had entered and remained unhurt were still subjected to rifle fire from the Confederates to the rear of the line.

The decision was made to rejoin the troops in the ditch, but few were left to obey the order. According to the official regimental history, between 15 and 20 men followed Griffith into the redoubt; only one returned with him alive. Without reinforcements, the desperate gamble gained little of substance. However, the flag of the 22nd still flew from the parapet, and its men waited below to try again.

They did not wait long, as the 77th Illinois arrived soon after to occupy the ditch to the right of the Iowans. Again men clawed their way up the steep exterior slope of Railroad Redoubt. Soon the 77th’s flag sat planted next to the 22nd’s, though no one from the 77th actually entered the fort. In early afternoon, a sortie from the 30th Alabama tried to retake control of the ditch, but was beaten back. Griffith then re-entered to accept the surrender of 13 Alabamians. Bitter fighting continued to swirl around the redoubt, with no one gaining a clear upper hand.

Meanwhile, just north of the Railroad Redoubt, the other main target of McClernand’s men would prove an equally tough nut to crack. Colonel Ashbel Smith and his 2nd Texas Regiment awaited the onslaught on their works, a type of earthwork known as a ‘lunette’ The 2nd Texas Lunette faced Brig. Gen. William Benton’s brigade of regiments from Illinois and Indiana. As 10 a.m. came, the cannon fire died out and the 99th Illinois moved forward in the lead, the men coatless in the late-morning heat. As they came near, some Yanks were heard to shout, ‘Vicksburg or hell!’

The fire from the Texans’ rifles was murderous, and a 12-pounder gun in the lunette belched canister at the Federal soldiers with deadly accuracy. The 99th and two of the three other regiments in the brigade veered to the left toward rifle pits manned also by the 2nd Texas. Corporal Thomas J. Higgins was captured, but not before carrying the flag of the 99th to the very edge of the Rebel rifle pits, braving the fire that cut down many beside him. (He was later awarded the Medal of Honor, based in part on the testimony of admiring Confederate foes.) The fourth regiment, the 18th Indiana, placed its flag on the edge of the lunette, but could do little more than watch it and wait for help.

That help came from Brig. Gen. Stephen Burbridge’s brigade. Within minutes his men rushed forward, shouting wildly, and gained the ditch before the lunette. Many of Burbridge’s men began to move up its side along with the men of the 18th Indiana. They reached one of two embrasures and poured rifle fire through it. The 12-pounder pointing out of the other embrasure was useless; Rebel artillerists were being shot down almost as soon as they could man it. Cotton bales between the two embrasures burned, set ablaze by muzzle blasts, which further increased the confusion and ferocity of the fight.

As the fort appeared ready to fall into Union hands, four Texans answered the call of Ashbel Smith to clear the embrasure. They jumped forward and, from five paces, fired their rifle-muskets into the opening. The leaders of the thrust fell dead, and the attack was blunted. The encouraged butternuts were soon rolling lit artillery shells into the ditch below to clear it.

The struggle for the 2nd Texas Lunette was not yet over, though. Burbridge’s Chicago Mercantile Battery hauled one of its brass 6-pounders up a gully near the lunette. The Chicago gunners then fired canister into the fort from 30 feet away. The point-blank artillery fire did not break the will of the Texans, and as morning wore into afternoon the fighting stalemated.

The morning fight had been undeniably bloody. Both Sherman and McPherson had committed only one brigade each to heavy action, but each had been badly hit. McClernand’s men did most of the fighting and dying. The 22nd Iowa was to lose 164 men killed, wounded or captured, most in the morning struggle. The brigade to which the 22nd belonged, Lawler’s, suffered 368 casualties over the course of the day, the most of any brigade in Grant’s army. All that had been gained was a shaky hold on one fort that could be loosened at any time.

In fact, by 11 a.m., Grant was ready to call off his troops. He had seen them struggle toward the forts against the galling Rebel fire. Before the smoke of battle obscured his view he saw them huddling in the ditches, with the flags of the 22nd Iowa and a few other regiments waving from several parapets. He rode to see Sherman, his most trusted lieutenant.

As he galloped north, he was overtaken by a note from McClernand, saying a timely blow from McPherson’s troops might swing the battle McClernand’s way. A second note arrived minutes later claiming possession of two forts and asking for a push all along the line. Grant was skeptical; he had had a better viewpoint of the battlefield than McClernand. He told Sherman, ‘I don’t believe a word of it.’

Yet on the strength of these notes and one later communication, Grant sent troops to support McClernand. After seeing the dispatches, Sherman decided to push again, but he did it with isolated units in three assaults. The first was at 2:15, when two brigades already in good position moved against the Stockade Redan complex. As had happened that morning, the Missourians and Mississippians within the fort shattered the approaching bluecoat contingent.

At 3 p.m., the Eagle Brigade, along with the 8th Wisconsin’s bald eagle mascot, ‘Old Abe’ advanced down Graveyard Road, used that morning by Sherman’s ‘forlorn hope’ and the two Ohio regiments. Though some troops made it to the fort’s ditch, their position was extremely tenuous and Sherman ordered them withdrawn. Finally, an attack at 4 o’clock involved Sherman’s remaining division unbloodied in that day’s action. This attempt too was blunted.

Meanwhile, McPherson’s reinforcements to McClernand were split up, some going to the 2nd Texas Lunette and some to the Railroad Redoubt. A Confederate counterstroke cleared the lunette of Federal troops not long after their arrival there. The remaining troops, sent to the redoubt, were told to attack and hold the trenches between the two forts.

Heartened by the sight of the 77th Illinois and 22nd Iowa flags still flying over the redoubt, Colonel George Boomer’s men advanced toward the trenches until they stopped in the bottom of an abatis-choked hollow. Before the lines could be re-formed, Boomer was shot dead and his men withdrawn. Late in the day, McPherson launched a half-hearted attack on the 3rd Louisiana Redan, in the Confederate center, which was quickly beaten back.

The Union attack was coming to a dismal end all along the line, yet one more drama remained to be played out. As long as the Railroad Redoubt was in Union hands, the Confederate line was breached and invited further attack. Stephen Lee, who had watched the Union troops swarming toward him that morning, repeatedly called for volunteers to close the breach. The troops of the 30th Alabama, exhausted and dismayed, did not step forward.

In desperation, Lee turned to men of the 2nd Texas, some of whom had been massed in support of the Alabamians since that morning. ‘Can your Texans take the redoubt?’ Lee asked. ‘Yes!’ Colonel James Waul replied. At 5:30, with a shrill Rebel yell, about 40 Texans (with several late Alabama volunteers) moved out along a narrow ridge swept by Yankee snipers. The fire and their exposed position did not halt them, and they pushed into the fort, driving the Federal occupants into the ditch below and sealing the last breach in the Vicksburg line.

The men in the ditch below now faced the rifle fire of the Texans and lit shells being rolled down the side. Lieutenant Colonel Harvey Graham, commanding the 22nd Iowa and the other 58 men there, surrendered after having spent almost eight hours under continuous fire.

The supposedly ‘whipped’ Rebels had taken on the triumphant Yankee army and inflicted on it a stinging defeat. The Army of the Tennessee had suffered over 3,000 casualties, more than in all other engagements since landing in Mississippi. Confederate casualties probably did not exceed 500.

The story of the lost battle lay in Union generalship. The performance of McPherson and Sherman, normally Grant’s two most reliable corps commanders, had been subpar. Sherman advanced little more than a token force in the morning, then attacked piecemeal in the afternoon, allowing the defenders time to regroup between attacks. McPherson also seemed halfhearted in his commitment to battle, throwing only one brigade at a time into the fight (though one division of his had been sent to McClernand in the afternoon).

McClernand did not face similar criticisms; all but one brigade under his command saw action. However, Grant (among others) attacked him for the misleading nature of the messages Grant received urging a renewed push. Grant believed the renewed assaults increased Union casualties by 50 percent, with little increased chance for a breakthrough. McClernand defended his actions, then and later, but the mood of the Army was against him. Grant now had a reason to sack him–McClernand was soon gone from command.

Grant knew the time for recriminations would come later. As night fell on the outskirts of Vicksburg that May 22, he wasted little energy on the past. A direct assault had been tried and failed, and his mind, characteristically, had already turned to the matter at hand. A bystander heard him say, perhaps to himself, ‘We’ll have to dig our way in.’

This article was written by Jeffry C. Burden and originally appeared in the May 2000 issue of America’s Civil War.

For more great articles be sure to pick up your copy of America’s Civil War.