Editor’s note: Like many George Armstrong Custer defenders, the author of the following article believes that Major Marcus Reno and Captain Frederick Benteen were to blame for the 7th Cavalry’s failure in Montana 120 years ago. And, like some of those Custer defenders, the author believes that Reno and Benteen tried to hide the truth. Part of that truth, the author suggests, may have been that Colonel Custer actually crossed the Little Bighorn River and fought in the Indian village.

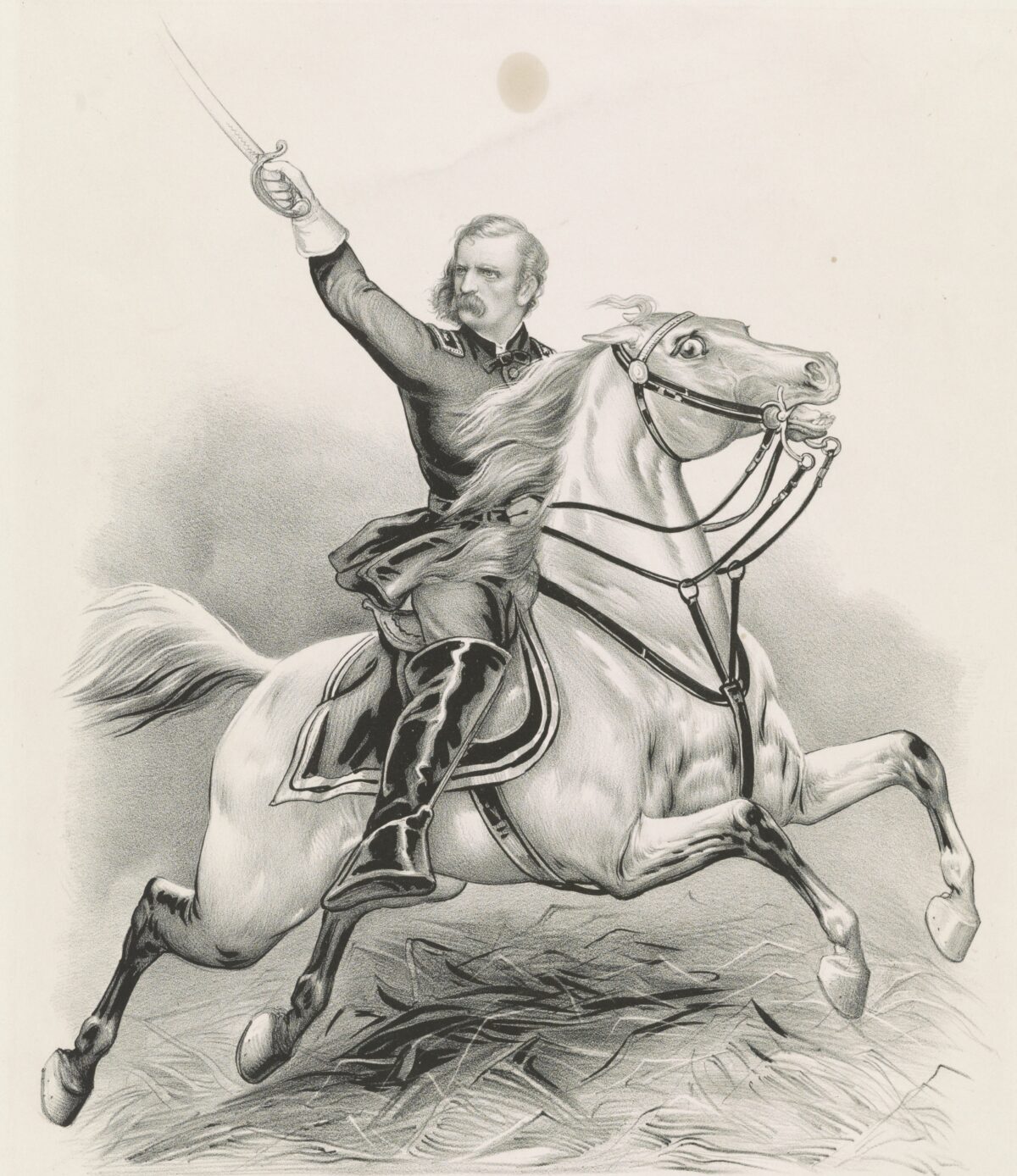

June 25, 1876. It has become a day of myth and mystery. On that date, Lieutenant Colonel (Brevet Major General) George Armstrong Custer and the 7th Cavalry fought perhaps the biggest alliance of Plains Indians hostile to the government that had ever gathered in one place. As every student of the American West knows, the 7th Cavalry lost that battle, and Custer’s personal command, about 210 soldiers, was wiped out. Without a survivor of Custer’s command to tell the story, with the possible exception of the young Crow scout Curley, it is only natural that the dramatic event would trigger more debate and conjecture than any other battle in U.S. history.

The entire 7th Cavalry was not destroyed in the desperate fighting. Under the command of Major Marcus Reno and Captain Frederick Benteen, about 400 soldiers and scouts survived a two-day siege on a bluff about four miles from where Custer was annihilated. On June 27, reinforcements commanded by Brig. Gen. Alfred Terry arrived on the battlefield to rescue the survivors and bury the dead of the 7th Cavalry. A coverup of the facts of the battle immediately began–a coverup endorsed by many, but orchestrated first and foremost by Major Reno and Captain Benteen.

Custer’s political difficulties during the spring of 1876 and his testimony in Washington, D.C., concerning governmental corruption on the frontier also kept the authorities from pursuing an investigation that might clear up some of the mystery. It was an election year, and President Ulysses S. Grant and his administration had no desire to elevate Custer from his former status of political enemy to that of martyr. Even General Terry confused the issues by inventing a charge that Custer disobeyed orders–a charge still frequently repeated despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary.

Orders were disobeyed at the Battle of the Little Bighorn, but not by Custer. Reno and Benteen had been ordered forward to attack the Indian village. Not only did the two officers fail to carry out those orders but they also failed to carry out the spirit of military duty as it exists historically in any military structure. Reno and Benteen, to protect themselves, went far in confusing the issues of the battle.

It was early morning on June 25 when, from the divide between the Rosebud Creek and Little Bighorn River valleys, Custer was informed by his scouts of the location of an enormous camp of hostile Indians, mostly Sioux and Cheyenne. Custer was also informed that the 7th Cavalry was under observation by hostile scouts. Because the Indians in the camp might escape–the greatest concern to the frontier army while on campaign–Custer ordered his force forward to the attack. Custer could do so with confidence, for there was no record up to that date of Plains Indians ever having confronted an entire regiment of U.S. cavalry, much less defeating them.

Dividing the regiment into four elements, Custer began the advance into the Little Bighorn Valley. The Indians were camped some 12 miles away. Custer himself commanded two battalions–five companies–and Reno commanded a third battalion of three companies. These three battalions made up the main force of the advance, while Benteen and three companies were sent on a controversial and somewhat mysterious’scout’ to the left (south) of the main advance. One company and several picked soldiers from each of the other companies made up the rear guard and pack-train escort.

As Custer’s and Reno’s forces neared the valley, hostile war parties were observed, as well as dust rising from the valley, indicating that there was activity in the village–probably that the Indians were preparing to flee. Reno was ordered to advance directly into the valley, while Custer turned to the right and took a route parallel to Reno’s advance.

While Custer has been criticized for his tactics in the battle, this maneuver was, in fact, a standard cavalry tactic. Both Custer and Reno were experienced Civil War cavalry officers and would have been very familiar with it. The official manual of the time (used during the Civil War and in the postwar period) was Cavalry Tactics and Regulations of the United States Army, written by Philip St. George Crook. Regulation 561 of that manual states, ‘If possible, at the moment of a charge, assail your enemy in the flank when [the enemy] is engaged in the front.’ Reno’s attack in the valley was to be a diversion, the ‘anvil’ so to speak, while Custer maneuvered to strike the flank, or be the ‘hammer’ of the combined attacks. Custer’s maneuver was straight out of the book.

Two messages are known to have been sent by Custer before his command was destroyed. The first message was brought by Sergeant Daniel Kanipe to the pack train, and the second message was sent with Private John Martin to Captain Benteen. Both messages ordered these forces to quickly advance to support the attack on the Indian village. It is after this point that many details of the battle become obscured, especially the movements of Custer and his five companies.

Although there are conflicting accounts by the survivors of Reno’s command about times and distances involved in the valley attack, it is known that after reaching the valley and advancing toward the camp for perhaps up to two miles, Reno halted his advance and deployed his soldiers as skirmishers, while the mounts were sent into a sheltered wooded area on the right of his line. When the now-alerted Indian warriors began to advance and flank his line, Reno withdrew his men to the wooded area and had them remount. After a bullet struck an Arikara scout, Bloody Knife, in the head, sending a shower of gore into Reno’s face, Reno led a disorganized retreat out of the woods and to the rear. The retreat turned into a total rout, during which Reno lost about a third of his command killed, wounded or missing.

Advancing toward the battlefield, Benteen witnessed Reno’s retreat and then joined Reno and his command on the bluffs. Custer had passed this very spot on his advance to attack the village, and farther downstream (at the position now known as Weir Peak, or Weir Point), Custer had been seen by members of Reno’s command before they retreated from the valley. The pack train soon joined Reno and Benteen on the bluff position, and all the hostile Indian forces that were in the area left. It was also about this time that the sound of gunfire, volley fire, was heard downstream.

At the Reno court of inquiry in 1879–the only ‘official’ investigation of the battle–nearly every participant that testified said he heard gunfire from downstream, and only Reno and Benteen claimed this gunfire did not occur. Among those who heard the gunfire were Lieutenant George Wallace, Lieutenant Charles Varnum, Captain Myles Moylan, Lieutenant Luther Hare and Lieutenant Winfield Edgerly. Most of these soldiers mentioned hearing ‘volley’ fire, which would indicate that Custer’s force was engaged.

The only known position that Custer and his soldiers fought at is on and around the hill (today called Custer Hill, or Last Stand Hill) where the soldiers were killed. This position is 4.1 miles from the Reno position (now known as Reno Hill), where the gunfire was heard. A mile north of the Reno position stands Weir Peak, a geographical formation that might affect any sound from Custer Hill. From the position of the bodies found on Custer Hill, it would appear most of the soldiers were fighting in skirmish formation and not close together–unlike how they would have stood if firing volleys under the direction of an officer. Background noise on Reno Hill, where there were more than 400 men and almost 600 horses and mules, must have affected the hearing of the soldiers there.

To further explore such matters, I created a task force of experts in 1994. Steve Fjstad, firearms expert and author of the Blue Book of Guns, was consulted concerning the question of the gunfire heard. In November 1994, Fjstad directed a sound test using a Springfield carbine and ammunition with powder loads that were similar to those used in 1876 (the cavalrymen at the Little Bighorn used .45-caliber Springfield single-shot carbines). Rick Van Doren, an acoustics expert, provided testing equipment; John Allan, another firearms expert, conducted the actual firing; and firing range supervision was provided by legal investigator John Swanson. Also attending the test was Edward Zimmerman, a lawyer and military law specialist. The results of this test indicate that it was unlikely the gunfire heard on Reno Hill originated from Custer Hill.

Terry Flower, a physics professor at the College of St. Catherine in St. Paul, Minn., conducted a second test in 1995, again using a Springfield carbine and appropriate powder loads. In a 25-page report on his test, Flower wrote, ‘Volleys heard at Reno Hill most probably did not originate from Last Stand Hill [about 7,000 meters away].’ Only on-site testing will answer the question with certainty, but such testing has not as yet been permitted at the Little Bighorn Battlefield National Monument (known until 1991 as the Custer Battlefield National Monument).

Still, if it is probable that gunfire from Custer Hill could not have been heard on Reno Hill on July 25, 1876, then where could the sound of gunfire have come from? Interestingly enough, there is testimony from the Reno court of inquiry that may suggest an answer. Sergeant Edward Davern testified: ‘Shortly after reaching the top [of Reno Hill], I heard volley firing from downstream….I could see Indians circling around in the bottom on the right, way down and raising a big dust….I spoke to Captain [Thomas] Weir about it. I said, ‘That must be General Custer fighting down in the bottom.’ He asked me where and I showed him. He said, ‘Yes, I believe it is.” Statements made by Lieutenant Edward Mathey and Lieutenant Edgerly supported Sergeant Davern’s observation.

The ‘bottom’ is, of course, where the Indian village was located. If Davern’s observation was correct, then it would indicate Custer had conducted a successful charge across the river–probably at Medicine Tail Ford, also known as Minneconjou Ford–and into the Indian camp. The testing done by Terry Flower indicates that shots fired near that ford could have been heard on Reno Hill. ‘U.S. Government Survey maps indicate that the Minneconjou Ford is located about 4,300 meters from the Reno entrenchment,’ Flower said. ‘While single shots could marginally be heard, volleys and multiple firings could most likely be identified.’ There are statements from Indians who were in the camp that seem to indicate soldiers were in the camp and fighting there. Indian participants such as Gall, Red Horse, Kill Eagle and Thunder Hawk mentioned women and children being killed and tepees set afire. There is no evidence that this killing and tepee-burning was done by Reno’s men, and most accounts from survivors of his command say Reno’s charge was stopped short of the village. Stray bullets could kill women and children, but they would not set tepees afire.

In his official report of the battle, Reno mentioned that Custer may have crossed the river and attacked the camp, but he later changed this view. Benteen, in a letter to his wife, also mentioned the possibility that Custer got across, but by the time of the Reno court of inquiry, he had changed his view: ‘I can’t think he [Custer] got within three furlongs of the ford.’

The distortions and untruths told by Reno and Benteen about the Battle of the Little Bighorn are so many and so obvious that almost everything they said about it becomes suspect. These ‘errors’ have been pointed out by many researchers. ‘There are many elements to this story that indicate that others besides Reno and Benteen were involved in a coverup of the facts, distortions and outright criminal acts,’ Zimmerman said. ‘Some of these issues require a more in-depth investigation to expose the truth.’

Zimmerman has made a detailed comparison of the map presented at the Reno court of inquiry with the map drawn by Lieutenant Edward Maguire, who was a member of General Terry’s command that arrived at the battlefield on June 27, 1876. Cartographer Phil Swartzberg discovered 10 noteworthy changes. Some of these may have been innocent in nature. Others, such as the addition of a spur to the bluffs between Reno’s hill position and the Indian village, seem to have been deliberately made. An enlisted men’s petition, signed by 236 surviving soldiers of the 7th Cavalry days after the battle, requested that Reno and Benteen be promoted. This petition was presented at the inquiry. A Federal Bureau of Investigation examination of this petition, dated November 2, 1954, discovered that a large number of the names were probably forgeries. The petition, along with the altered map, suggest there was a well-thought-out military coverup designed to discredit Custer–call it ‘Custergate.’

Zimmerman is now pursuing a legal appeal to the court’s finding that ‘the conduct of the officers throughout was excellent and while subordinates in some instances did more for the safety of the command by brilliant displays of courage than did Major Reno, there was nothing in his conduct which requires animadversion of the court.’ If Custer did cross the river and fight in the Indian camp, that would be something Reno and Benteen would desperately try to hide, for if Custer was fighting in the village and they failed to come to his assistance, then any rational defense of their actions becomes impossible. And if Custer did fight in the village, then all the many accounts of the battle to date are incomplete. Only further on-site research and study, with the scientific tools of the 20th century, will shed more light on this possibility. In June 1996, Flower will conduct more acoustics tests near the battlefield. The tests, according to the professor, will not conclusively confirm where Custer was when the shots were heard on Reno Hill, but they will’say which positions could be eliminated from consideration. And that should take us one step closer to understanding the sequence of events of June 25, 1876.’

This article was written by Robert Nightengale and originally appeared in the June 1996 issue of Wild West.For more great articles be sure to subscribe to Wild West magazine today!