MY LAST COLUMN EXAMINED The Desert Fox, the well-known 1951 film that helped popularize the image of Field Marshal Erwin Rommel as a gallant, principled soldier who stood up to Hitler and supported the attempt to remove the Nazi dictator from power in the summer of 1944. Rommel, a German television film first broadcast in 2012, depicts a very different man. “I don’t see him as a hero,” said writer-director Niki Stein. “He is a tragic figure. He was a weak man drawn into an incredible internal conflict.”

MY LAST COLUMN EXAMINED The Desert Fox, the well-known 1951 film that helped popularize the image of Field Marshal Erwin Rommel as a gallant, principled soldier who stood up to Hitler and supported the attempt to remove the Nazi dictator from power in the summer of 1944. Rommel, a German television film first broadcast in 2012, depicts a very different man. “I don’t see him as a hero,” said writer-director Niki Stein. “He is a tragic figure. He was a weak man drawn into an incredible internal conflict.”

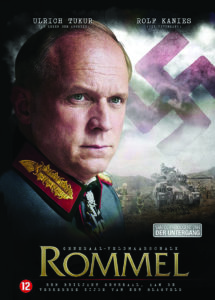

To make this point, Rommel examines the last 10 months of the field marshal’s life. Rommel (portrayed by Ulrich Tukur) comes across as an average military talent—a competent division commander, says Field Marshal Gerd von Rundstedt (Hanns Zischler), promoted well beyond his abilities. He has gotten as far as he has only because of Hitler’s patronage and the worshipful publicity supplied by Joseph Goebbels, the Nazi minister of propaganda.

Although not officially a member of the Nazi Party, Rommel might as well be. He is among the members of the German high command who visit Hitler at his private mountain retreat in Berchtesgaden to swear fealty to the dictator. Rommel tells his chief of staff, Lieutenant General Hans Speidel (Benjamin Sadler), that he has heard of terrible things about “mass executions” and “the massacre of the Jews in the occupied territories.” He asks Speidel, who has served on the Eastern Front, if he can confirm this. Speidel does. Rommel merely digests this information. As he says later in the film: “That’s just politics. We’re soldiers. Politics doesn’t concern us.”

The Holocaust may not concern other members of the Wehrmacht either, but Germany’s deteriorating military position does. Speidel puts Rommel in touch with General Carl-Heinrich von Stülpnagel (Hubertus Hartmann), who tells him of a conspiracy afoot to arrest Hitler and put him on trial for war crimes in hopes that Germany can then negotiate peace. Rommel responds that Stülpnagel is proposing a military coup; he indignantly refuses to go along.

A point in Rommel’s favor is that he does not report his knowledge of the conspiracy, but that is as far as he goes. Instead, after D-Day he approaches Hitler and edges toward asking him to consider a negotiated peace. Hitler demands that Rommel restrict himself to discussing purely military matters. The Allied nations will never negotiate with his regime, says the dictator. All that is left is the fanatical resistance of each and every German. “Are you prepared to do this?” he demands of Rommel, who gives no indication that he is not.

On July 9, the field marshal meets with Lieutenant Colonel Caesar von Hofacker (Tim Bergmann) and learns that the conspiracy now focuses on assassinating Hitler. He asks if Rommel will work for “a different Germany, with a different government.” The film cuts immediately to another scene, with the clear implication that Rommel has once again refused to go along.

Rommel toys instead on the idea of opening the front and allowing the Western Allied forces to pass through, but nothing comes of this. On July 17, he is gravely wounded when a Spitfire strafes his staff car. Three days later, a bomb explodes in Hitler’s headquarters. It fails to kill the dictator and the conspirators are quickly rounded up. One of them implicates Rommel, but only of knowing about the assassination plot. Rommel’s involvement extends no farther than his failure to report this knowledge to the Gestapo.

That, however, is enough. On October 14, two generals visit Rommel at his home, where he is recuperating, and accuse him of conspiring against Hitler. “What?” Rommel asks in surprise. The generals tell him that he can either undergo public trial, in which case his family will suffer, or take cyanide, in which case his family will be left alone and his wife will receive his full pension. Rommel agrees to commit suicide. He leaves with the generals, but maintains to the last, “I am innocent.”

Needless to say, the film outraged the field marshal’s elderly son, as well as his granddaughter and one military historian who had cooperated with its production, all of whom believed the film downplayed Rommel’s role in his resistance against Hitler. But Rommel matters less for its accuracy or inaccuracy than its portrayal of a figure who is a proxy for ordinary Germans. Hitherto, German film depictions of life under Hitler’s regime drew a sharp distinction between the Nazis and ordinary Germans, who were shown as being themselves victims of the regime. Rommel runs directly counter to this reassuring picture. “Please watch, this film explains a little how it was back then with our grandparents, with Hitler, with fear, with joining in,” pleaded one German columnist. “The Rommel film shows how a man believes he is serving a king and realizes too late that he is a devil.” ✯