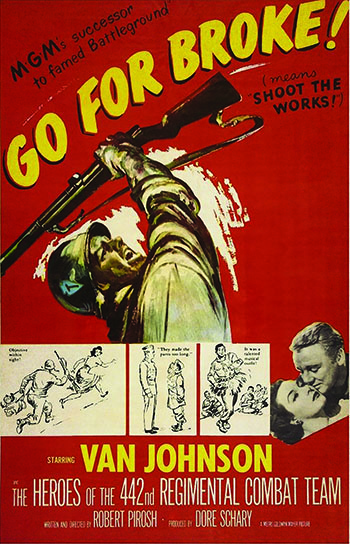

IN 1950 ROBERT PIROSH, fresh from the success of his Academy Award-winning screenplay for Battleground, an acclaimed film about a squad of American soldiers fending off Germans during the Battle of the Bulge, turned to a new project. He wanted to make a movie that would illuminate the lives of the 120,000 Japanese Americans “back in 1943, when the ugly flame of race prejudice was being fanned by war hysteria.” Directing the film himself, Pirosh focused on the 442nd Regimental Combat Team, a highly decorated unit of Japanese Americans that fought during the Italian campaign and later in France. The result, Go for Broke!, premiered in May 1951 to wide acclaim.

But despite Pirosh’s desire to emphasize race prejudice, most reviewers treated Go for Broke! as a first-rate battle film—which indeed it is—and paid only slight attention to the fact that most members of the 442nd came from the archipelago of relocation camps the U.S. Army had created for Japanese immigrants—Issei—and their American-born offspring, Nisei, who were U.S. citizens.

The reviewers could be pardoned for doing so. Although Go for Broke! does highlight prejudice, it is embodied primarily in Lieutenant Michael Grayson (Van Johnson), a former Texas National Guardsman who finds himself in charge of a platoon of Nisei soldiers. The film opens as Grayson arrives in camp, plainly dismayed by his new assignment. No sooner does he report to his commanding officer than he requests a transfer to his former unit, the 36th Infantry Division, composed of the Texas National Guard. Grayson says he has nothing against leading “Japs,” but the colonel doesn’t believe him. The soldiers aren’t “Japs,” he replies. “They’re Japanese Americans—Nisei—or as they call themselves, ‘Buddha-heads’…. They’re all American citizens and they’re all volunteers. Remember that.”

Grayson isn’t convinced, and when he encounters his company commander he acidly inquires whether the trainees are issued live ammunition on the rifle range. “A Jap’s a Jap, eh?” responds the captain. Grayson responds sarcastically that maybe the Japanese relocation program arose because the army had a surplus of barbed wire. This earns him a second lecture. “The army was facing an emergency at the start of the war,” the captain explains. “A possible invasion by Japanese troops. So all Japanese Americans were evacuated from the West Coast. There was no loyalty check, no screening, nothing.” As for the members of the 442nd, they’ve been “investigated, reinvestigated, and re-reinvestigated.” They are true-blue Americans.

Whether Pirosh knew it or not, the perspective of Grayson’s commanding officers aligned perfectly with the Orwellian wartime propaganda films the U.S. government issued, depicting the government’s removal of thousands of mostly loyal Japanese Americans to relocation camps as regrettable but humane. Scene after scene showed evacuees cheerfully accepting their lot and actively assisting the operation. “The many loyal among them believed that this was a sacrifice they could make on behalf of America’s war effort,” a 1942 documentary assured audiences. “The evacuees are not under suspicion,” explained another documentary. “They are not prisoners. They are not internees. They are merely dislocated people. The unwounded casualties of war.”

But whatever the government’s bland official story, pressed upon Grayson by his commanders, the film’s many scenes with the platoon offered ample scope for expressions of bitterness at the irony of fighting for a country that had imprisoned their families. By and large, though, Pirosh ignored this opportunity. A single member does speak out persistently against the injustice of internment, but his comrades treat this as a simple case of grousing and think he should be philosophical about it.

Thus “the ugly flame of race prejudice” burns primarily in Grayson and, toward the end of the film, in some of his buddies in the 36th Division. The focus on the 36th is no accident. Historically, in October 1944, German forces in eastern France’s rugged Vosges Mountains cut off a battalion of the 36th, which elements of the 442nd save in a rescue that forms the film’s climax. Go for Broke! concludes with newsreel footage of President Harry S. Truman presenting the 442nd with a Presidential Unit Citation, followed by a final scene in which Grayson, now thoroughly converted from his misplaced prejudice, proudly marches at the head of his platoon.

Almost four decades would intervene between the premiere of Go for Broke! and the day President Ronald Reagan signed the Civil Liberties Act of 1988, by which the U.S. government paid $20,000 to surviving internees and admitted the relocation was the product of “race prejudice, war hysteria, and a failure of political leadership.” Audiences and film critics who applauded the film would have had scant inkling such a reckoning was needed. Far from forcing them to confront the “war hysteria” that robbed 120,000 Americans of their civil rights, Go for Broke! neatly got the United States off the hook.