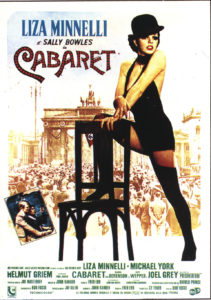

FEW WORLD WAR II FILMS portray how the Nazis came to power. Those that do typically focus on Adolf Hitler. But one important exception is Cabaret, the acclaimed 1972 musical directed by Broadway legend Bob Fosse, for which Liza Minnelli won the Oscar for Best Actress for her breakout performance as American expatriate and chanteuse Sally Bowles.

Extraordinarily dark, Cabaret is one of a handful of movies that show how ordinary people experienced the Nazi takeover in Germany.

The film begins in 1931 Berlin at the Kit Kat Klub, one of many cabarets that dot the German capital. The evening festivities are in full swing, with one bawdy act after another presided over by the club’s leering emcee—the master of ceremonies, portrayed by Joel Grey—his face covered with white grease paint and garish rouge.

The revelries culminate in a mud wrestling match between two women, whom the emcee sprays with seltzer water while mugging for the crowd. Almost unnoticed, a Nazi Brownshirt meanders through the audience, soliciting donations for the Party until the maître d’ kicks him out the door. Oblivious to this development, the emcee concludes the act by slapping a dollop of mud across his upper lip, in a mocking imitation of Hitler, and stretching out his arm in a Nazi salute.

Cabaret is a decidedly nontraditional musical. In most musicals, characters break into song as part of the dialogue. However in Cabaret, the songs are not so much a part of the storyline as a commentary upon it. And every performance—with one chilling exception—takes place in the Kit Kat Klub.

Thus, the evening after the Brownshirt is ejected from the Kit Kat Klub, his compatriots corner the maître d’ outside in an alley and brutally beat him. The punches and kicks are intercut with scenes of a slapstick skit on the cabaret stage, where the emcee pretends to strike the cheeks of women clad in Bavarian folk costumes and merrily slaps their fannies.

A subplot involves a love affair between two friends of Sally: the beautiful Natalia Landauer (Marisa Berenson) and Fritz Wendel (Fritz Wepper). Natalia is Jewish. So is Fritz, but to avoid the gathering anti-Semitism in Germany he has passed himself off as Protestant. Fritz decides to acknowledge his real heritage when he realizes that Natalia will marry only a Jewish man. On stage, the emcee dances with an actress costumed as a gorilla, proclaiming his love for her and asking the audience to see the gorilla as he does. “If you could see her through my eyes,” he concludes plaintively, turning to the crowd and dropping to a conspiratorial whisper, “she wouldn’t look Jewish at all!”

Fixated on becoming a rich and famous movie star, Sally scarcely notices the shifting political currents around her. Not so her friend and sometime lover, Brian Roberts (Michael York), an English doctoral student. Brian sees the loathsome Nazis everywhere—and grasps the threat they represent.

He understands the rising danger more than most Germans do. While he and Sally are on a drive through Berlin with a wealthy young aristocrat, Maximilian von Heune (Helmut Griem), Max’s chauffeur-driven limousine passes the bloody corpse of a Communist agitator murdered by Nazi street thugs. Unruffled, Max assures Brian, “The Nazis are just a gang of stupid hooligans, but they do serve a purpose. Let them get rid of the Communists. Later we’ll be able to control them.”

“But who exactly is ‘we’?” Brian inquires.

“Germany, of course.”

A few days later, Brian and Max find themselves on the patio of a beer garden. Suddenly a young tenor voice, clear and sweet, begins to sing a folk song extolling Germany’s natural beauty. The crowd quiets to listen. The camera cuts to the youth’s blond Aryan head, then slowly pans downward to reveal a swastika on his left arm and the boy in full Nazi uniform. “Somewhere a glory awaits unseen,” he continues; “Tomorrow belongs to me.”

The folk song shifts in meter to a driving militaristic tempo. The boy, joined one at a time by other German youth, then by nearly the entire crowd, begs the Fatherland to show them a sign “Your children have waited to see / The morning will come when the world is mine / Tomorrow belongs to me.”

By this time the youth is fierce in appearance, the bellowing customers filled with both anger and pride. Returning to their limo, Max and Brian look back at the crowd. “Do you still think that you can control them?” Brian asks.

Then, as if to comment on the action, the film cuts back to the emcee. He looks up, faces the viewer, smiles that leering smile, and nods. The nod isn’t meant to answer Brian’s question, but rather to acknowledge what the audience is thinking. Yes, the emcee seems to say, this is just how it came about.

The “real” Germany was never the Germany of Max’s aristocratic imaginings, but rather that of those ordinary volk—the people—lifting their tankards, summoning not morning, but the blackest night.