Private Alfred Rolls was tired and cold.

The 40-year-old was a member of the Australian army reserve’s 22nd Garrison Battalion, which provided guards for the No. 12 Prisoner of War Camp near the small town of Cowra in rural New South Wales. On the cold winter’s night of Aug. 5, 1944, Rolls was the lone sentry posted at the heart of “Broadway,” the brightly lit strip of bare ground that bisected the sprawling circular camp. A small canvas tent, a standard wooden office chair and a telephone connecting his lonely post to the main guardhouse were his only comforts. Facing the center of camp were double gates leading to each of the four prisoner compounds, and Rolls was to watch for any motion from inside. To keep his circulation going, the middle-aged guard kept moving, strolling and stamping his frigid feet on the hard-packed dirt.

Though uncomfortable, his guard shift was uneventful. Then, shortly before 2 a.m., he noticed a figure bobbing among the buildings in B Compound—the northeast quadrant of camp, which housed some 1,100 Japanese POWs. As the figure ran toward the compound gates, Rolls realized the man was trying to get his attention. The prisoner quickly scaled the inner gate and approached the outer gate, all the while speaking rapidly in Japanese. Not understanding the language but noting the man’s frantic state, Rolls assumed the worst, pointed his rifle in the air and fired two shots—the prearranged alarm signal. Moments later his telephone rang. The guard picked up the receiver and reported what he had seen.

What Rolls had seen was the opening act of what would become the largest mass POW escape of World War II.

Opened in June 1941, Cowra initially housed Italian POWs shipped to Australia from the battlefields of North Africa, as well as Indonesian civilian internees. Following the British Commonwealth’s declaration of war on Japan that December 8 the camp was enlarged to accommodate anticipated Japanese prisoners. The first arrived in Cowra soon after the January 1942 onset of the Allied campaign in New Guinea.

The camp comprised four compounds—A, B, C and D—each guarded by a 100-man company of the 22nd Garrison Battalion. Italians from the North Africa campaign were in A and C, to the northwest and southeast, respectively. Japanese officers, as well as Koreans and ethnic Chinese from Formosa (present-day Taiwan) attached to the Imperial Japanese Army, were held in D Compound, to the southwest. B Compound was the primary Japanese prisoner complex, holding warrant officers, noncommissioned officers and enlisted men.

Australian and U.S. forces had captured the Japanese amid the fighting on New Guinea. Having arrived in the combat zone with only basic supplies and few effective medicines for the tropics, the Japanese had suffered all jungle warfare had to offer. Malaria, parasitic and fungal infections, insect-borne diseases, malnutrition and poorly treated wounds took their toll as the campaign turned inexorably in favor of the Allies. When captured, many of the Japanese were in a semicomatose state or unconscious from wounds.

After initial questioning, those Japanese POWs considered of value to Allied intelligence services were flown to Brisbane for further attention by the Allied Translator and Interpreter Section. Its interrogators—including Japanese-American soldiers—employed a highly structured process to cull useful information. Finding themselves in an alien environment and unable to rationalize their situation, Japanese POWs were often at a loss. During training they had not been advised how to handle interrogation, simply because capture was unthinkable; one was expected to die fighting. Their resulting bewilderment prompted bizarre levels of cooperation and seeming betrayal of their fellow Japanese. When asked a question, most of the POWs simply answered, often revealing sensitive information. Most captives “broke” after the first two days and willingly provided answers for up to two weeks. After that the information tended to be embellished, even fabricated, as prisoners gained familiarity with their surroundings and looked to continue the benefits of cooperation.

When their value as useful sources expired, the POWs were in for a long train ride—nearly 600 miles south from Brisbane to Sydney, then another 200 miles west to Cowra.

By mid-1944 the Cowra camp was bursting at the seams, and a mass transfer was in order. On Friday, August 4, Maj. Robert Ramsay, the commandant in charge of B Compound, summoned the Japanese POWs’ leaders—Sgt. Maj. Akira Kanazawa and Sgts. Maseo Kojima and Hajime Toyoshima (aka Tadao Minami)—to an afternoon meeting in his office. There Ramsay abruptly told the men that 700 prisoners, all those below the rank of lance corporal, were to be moved to the POW camp outside Hay, an even more isolated community some 270 miles farther west. The trio forcefully objected to the plan, insisting the Japanese were family and must stay together. Ramsay dismissed their protests and ordered them to have the men ready to move first thing Monday morning.

Rebuffed and resentful, the Japanese leaders returned to B Compound and told their fellow prisoners to begin gathering or making weapons. The POWs duly collected baseball bats provided by the Australians for recreation and raided the compound’s mess hall for knives and other metal cutlery. Though the latter implements were to have been counted by the guards and stored in a safe location after every use, the cutlery had never been secured. Purloined garden and carpentry tools rounded out the prisoners’ arsenal.

The Japanese leaders’ anger at the news didn’t overly concern the Australians, who apparently believed Cowra to be escape-proof. If such was the case, the captors obviously hadn’t been paying attention. Sixteen months earlier a noncom POW from B Compound had escaped, alone and with apparent ease. He was captured after nine hours on the run, and during a subsequent inquiry he demonstrated his method of escape. The man required just two minutes and 40 seconds to get over the triple row of 6-foot-high perimeter fences, and he smoked a cigarette during the entire exercise. Cowra’s commanding officer, Lt. Col. Montague “Monty” Brown, had afterward pleaded with military authorities in Sydney to bolster security at the camp. Despite his recommendations, the fences remained scarcely taller than the average man.

That lapse was to have deadly consequences when the coordinated breakout—part military operation, part mass suicide—exploded without warning moments after Alfred Rolls fired his two shots into the air.

From the door of a hut some 200 yards from where Rolls stood, one of Sgt. Minami’s men turned and shouted inside, “Minami-san, there’s an informer at the wire!” A dozen Japanese sprang from the hut in pursuit but failed to reach the informer before he clambered over the second gate into Broadway.

Realizing they’d lost the element of surprise, Minami sounded a bugle, signaling hundreds of prisoners to swarm from their huts, repeatedly screaming “Banzai!” at the top of their lungs. Despite the seeming chaos, each group had an objective. One mass of men ran north in a suicidal charge on a section of perimeter fence defended by machine guns, another pressed east toward the surrounding bush, while a third group spilled into Broadway to rush the north and south main gates. POWs in the latter group soon caught up to the informer. Clubbing the man to the ground, they cut his throat and kicked his body aside.

Meanwhile, Rolls was running for his life south down Broadway, lungs burning and heart pounding. Guards opened the main gates just enough to allow his passage, then quickly slammed them shut. Seconds later a screaming mass of prisoners hit the gates like a tidal wave. Rifle fire kept them at bay, but by that point 18 of the 21 prisoner huts and two other buildings were ablaze.

As the fight along Broadway unfolded, the eastbound group of POWs headed toward a section of perimeter fence near F Tower. Careful observation over the preceding weeks had allowed the Japanese to work out the towers’ fields of fire and determine the areas where they would be most safe from the guards’ weapons. On the prisoners’ approach tower guard Pvt. Kevin Mancer quickly burned through the five box magazines he’d been provided for his 9 mm Owen submachine gun. Though he had hand grenades, the tight confines of the tower kept him from extending his arm back far enough to hurl the projectiles with any distance or accuracy. Throwing blankets across the wire, the Japanese fled en masse into the darkness.

Among the ringleaders rushing the eastern perimeter was Yoshio Shimoyama, who while doing so committed an act of brutality that horrified even the hardened Japanese. On encountering a badly wounded countryman at his feet, he produced an improvised knife and unhesitatingly stabbed the injured man in the throat, killing him. (Four days later fellow Japanese POWs who had witnessed Shimoyama’s wanton cruelty meted out his execution, strangling him for the crime.)

The unfortunate group of POWs sent north against the two Vickers machine guns faced a murderous crossfire of .303-caliber bullets. But they just kept coming, clambering over the bodies of their dead countrymen to blanket and vault the perimeter fences in turn. Once over the outer fence, several of the escapees went after Pvts. Ben Hardy and Ralph Jones, the duo manning the closest Vickers gun.

When the initial alarm had sounded, two teams of two men each had raced toward the machine guns, which were mounted on separate four-wheel trailers—No. 1 near the north main gates, No. 2 slightly to the east. Hardy and Jones quickly got No. 2 gun into action, but the relentless Japanese were soon streaming over the outer fence. The gunners could have easily saved their lives by abandoning the gun and its store of ammunition belts. Instead, they remained at their post and acted with cool resolve. Summoning all of his courage, Hardy stopped firing. Telling Jones to run for it, he then lifted the Vickers’ top cover, removed the feed block and tossed it aside, ensuring the weapon could not be fired by the Japanese, who were soon clawing their way onto the trailer. They viciously beat and stabbed Hardy to death. Despite stab wounds to his chest and back, Jones managed to break free. Arriving at the other gun, he mumbled a couple of words before also falling dead. (For their actions Hardy and Jones each received a posthumous George Cross, the noncombat equivalent of the Victoria Cross.)

When the Japanese atop the No. 2 machine-gun trailer turned the Vickers on their captors and found the unfamiliar weapon wouldn’t fire, they fumbled for a solution. The delay enabled rifle-bearing guards to advance and kill them. Meanwhile, the gunners on the No. 1 Vickers kept firing and finally suppressed the mass attack on the north perimeter.

Inside the wire, on the north end of Broadway, guards from A and B compounds were firing rifles and a Bren gun into the Japanese rushing the gates. Three of the Australians were wounded by friendly fire from guards at the south end of Broadway, who kept shooting into the group of escapees attacking that end of camp. Able-bodied guards carried the injured men to safety in nearby huts as the POWs continued to assault the north main gates under heavy fire. One determined prisoner managed to scale the gates with an improvised dagger and club in hand. Dashing past guard Wal McKenzie, the lone escapee ran toward the B Company buildings, en route stabbing Pvt. Charles Shepherd in the heart and killing him instantly. Major Ramsay witnessed the killing and ordered one of his soldiers to shoot the Japanese, who soon lay dead mere yards from Shepherd’s body.

On the south end of Broadway prisoners sought to link up with the officers in D Compound. When one of the officers, physician Ichiro Fujita, moved to join the surge, Cpl. Don Angwin, a skilled marksman brought in from the nearby military training camp, put a bullet through each of Fujita’s thighs. The doctor bled to death where he fell. His death heralded the end of the Cowra breakout, which had lasted just 30 minutes.

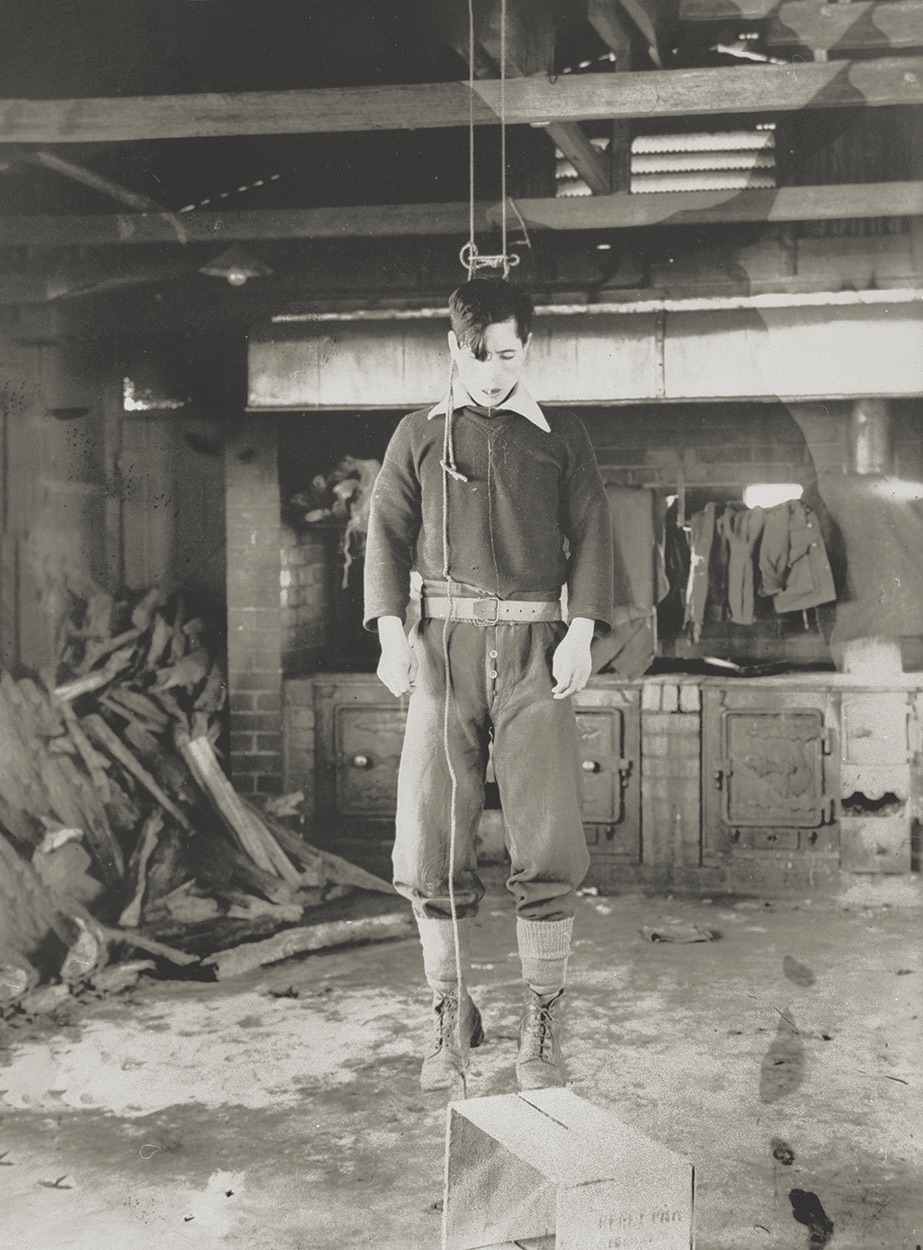

While the Australian guards had killed 180 Japanese POWs during the mass escape attempt, more than 300 others had made it into the bush. Late on the afternoon of the breakout eight of the escapees ambushed a group of young Australian recruits searching a wooded area west of the camp. The recruits had been issued only with bayonets, and when the Japanese attacked, they fell back while their leader, Lt. Harry Doncaster, tried to fight off the assault with his fists. Tragically, the Japanese used a bayonet one of Doncaster’s own recruits had dropped to kill the young officer. All eight escapees later hanged themselves from nearby trees.

The breakout indirectly resulted in the death of one more Australian. Volunteer Defence Corps Sgt. Thomas Hancock was dismounting from a truck to patrol the local rail lines and bridges when a soldier stepping from the same truck accidentally discharged his rifle into the sergeant’s buttocks. Though the wound appeared superficial, Hancock died of septicemia nine days later.

In the days following the breakout small groups of roaming and lost Japanese met a variety of fates at the hands of locals. While one shotgun-wielding farmer gunned down two of the escapees, others treated the POWs more benignly. When a trio of Japanese showed up at Walter and May Weir’s family farmhouse, for example, Mrs. Weir insisted they sit down for tea and scones while her daughter fetched the police from Cowra.

Back at camp Australian doctors treated wounded prisoners with minor injuries, while more serious cases were sent in ambulances to the military hospital at Goulburn, some three hours’ drive to the southeast. Of the 108 Japanese wounded, only three died of their injuries—a testament to the care provided them.

By the time the manhunt ended, the final death toll stood at 231 Japanese and five Australians.

For Australian authorities the aftermath was mixed. Mindful of their own 22,000 men being held in Japanese POW camps, they had to investigate and report the incident carefully. A press ban went into immediate effect. Not until September 9 did Prime Minister John Curtin make a public announcement regarding the breakout, citing a riot by Japanese POWs. A propaganda report picked up soon after on Japanese radio declared the dead could not have been prisoners of war, as Japanese soldiers never surrender. Instead, the report accused the Australians of “the cold-blooded murder of Japanese civilian internees.” A meticulous military court of inquiry, which delivered its findings to Tokyo via the Swiss Consulate in Sydney, put any such nonsense to rest. It found conditions at the camp exemplary and the actions of the officers and guards of the 22nd Garrison Battalion both necessary and measured. An independent inquiry by the Swiss backed up the findings.

In January 1945 Australian authorities charged breakout leader Akira Kanazawa with murder—more specifically with actions that resulted in the death of Vickers gunner Ben Hardy. Acquitted of that charge, Kanazawa was found guilty of “conduct prejudicial to good order and discipline” and handed an 18-month sentence he wouldn’t serve out. In March 1946 he and the surviving Japanese POWs from the Cowra and Hay camps were repatriated on the Japanese steamer Daikai Maru.

Cowra has experienced much healing since the 1940s. Indeed, the town—home to a stunning Japanese garden and cultural center and the only Japanese war cemetery outside of Japan—has become emblematic of the positive present-day relationship between Australia and Japan. Former POWs and their onetime guards convened in Cowra on numerous occasions over the decades to revisit the scene of the deadly escape attempt. The elderly Japanese, in particular, found comfort in visiting the graves of dead comrades and paying their respects at the graves of the Australians.

Far from being ashamed of having been prisoners, some formed associations back in Japan to recognize that consequential time in their lives. Masatoshi Kigawa, president of the group Cowra Kai, spoke openly about his wartime experiences, in particular the suffering he and his fellow Japanese had endured in New Guinea:

Who helped us? It was the Australian army. They took us back to Australia and took every possible care of us, providing us with food, clothes and shelter. Though they had a right to compel us to engage in work in the light of public international law, they tolerated our rejection and did not compel us. We were impressed with a humanitarianism rooted in the Australian army, thanks to which we acted as we liked and led a relatively easy life [in camp].

The present-day Cowra POW Campsite preserves the memory of the breakout and those Japanese and Australians who died. Covering several acres, the site includes the garrison gates, a replica guard tower, a visitor center and the POW Hologram Theater, where interactive displays relate the story of the mass escape and its aftermath. Those who survived the bloodletting would never forget.

For further reading Graham Apthorpe recommends his own A Town at War and The Man Inside, as well as Die Like the Carp! by Harry Gordon, and The Night of a Thousand Suicides, by Teruhiko Asada.