As the three large flying boats turned into the wind, their wakes formed graceful arcs. Approximately 1,200 people—U.S. Navy personnel, reporters and families of the crews—watched from the shore at the Rockaway Beach Naval Air Station as the aircraft climbed. Also on hand were 60 Curtiss workers, led by superintendent Peter Jensen, who had worked feverishly to put the final touches on the flying boats they had built. The three planes turned eastward and soon disappeared into the haze. At 10 a.m. on May 8, 1919, John H. Towers sent word that the planes had left Long Island on the first attempt to fly across the Atlantic Ocean. At noon Assistant Secretary of the Navy Franklin D. Roosevelt sent the following message: ‘Commander John H. Towers, U.S.N., USS NC-4. Delighted with successful start; good luck all the way — Roosevelt.’

The idea of a transatlantic flight by flying boat was proposed as early as 1914 and backed by philanthropist Rodman Wanamaker, who had asked Towers and Lieutenant J.C. Porte of the Royal Navy to pilot an aircraft designed by Glenn Curtiss. In the spring of 1914, Curtiss built a flying boat with a 72-foot wingspan, mounting three engines capable of a total of 480 hp. Christened America, the new plane had capacity for ample fuel, food and two pilots. However, when World War I broke out, the plan was canceled and America was sold to the British for maritime patrol service.

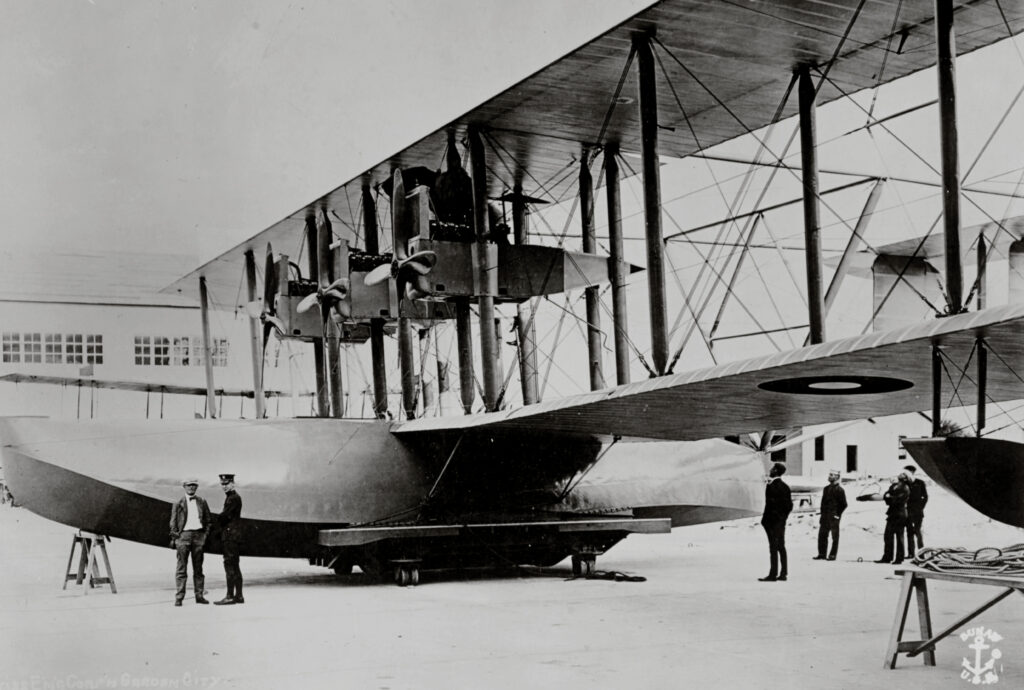

When the United States entered the war in April 1917, the U.S. Navy also needed flying boats to patrol against German U-boats. Curtiss had supplied the British and Russians with flying boats throughout the war and was among the premier designers and manufacturers of the type. In 1917 the Navy and Curtiss decided to work together to produce a new large aircraft to be known as the Navy-Curtiss (NC) flying boat. Chief naval constructor Admiral D. W. Taylor wrote, ‘The ideal solution would be big flying boats or the equivalent, that would be able to fly the Atlantic to avoid the difficulties of delivery, etc.’ The new flying boats—affectionately known as ‘Nancies’—had a wingspan of 126 feet (larger than that of a Boeing 727) and an overall length of 69 feet. They originally had three tractor Liberty engines that produced 1,200 hp. One engine was centrally installed above the fuselage, and the other two were supported on each side, between the upper and lower wings. Fully loaded, NC-1 weighed 24,000 pounds. One of its weight-saving innovations was to mount the tail on outriggers supported from a short, rugged hull. Under the supervision of Commander H.C. Richardson, the shape of the hull was refined using model testing to determine the best configuration for takeoff and taxiing.

Work on the first aircraft began at the Curtiss Engineering Corporation in Garden City, Long Island, during January 1918. NC-1 made her maiden flight on October 4, 1918, at Rockaway, with Richardson and Lieutenant David H. McCulloch as pilots, and was still undergoing flight testing when the armistice was signed on November 11, 1918.

The NC flying boat had originally been designed for transatlantic flight, and that goal was revived during the winter of 1918-1919, when naval officials made plans to fly to Europe in May 1919. It was decided that since the crews would be sent out by government orders, rather than on their own initiative, they must have the best available equipment and be furnished with all possible support. The route chosen had a 1,200-nautical-mile hop to the Azores as its longest leg rather than the 1,900-nautical-mile trip to Ireland across the treacherous North Atlantic. Three aircraft would attempt the trip, NC-1, NC-3 and NC-4. As NC-1 had been damaged during a March storm, one wing of the experimental NC-2 was used to refit it. To increase the margin of safety, a fourth pusher-type engine was added behind the original central engine.

Next, the Navy selected crews to man the three planes, appointing Towers as commanding officer. Crews came from the Regular Navy, the Naval Reserve and the U.S. Coast Guard. Towers chose NC-3 as his flagship, and Richardson was picked as chief pilot. Patrick N.L. Bellinger was chosen as commander for NC-1 and Albert C. Read for NC-4. Marc Mitscher, originally picked to command the now scrubbed NC-2, became NC-1‘s pilot. In addition, the airplanes carried radio operators, flight engineers and mechanics.

During WWI, Richard E. Byrd had experimented with a number of scientific instruments, ranging from drift indicators to bubble sextants, that were useful in navigating over water, without visual landmarks. Although Byrd lobbied hard to join the 1919 flight, instead the Navy assigned him to plan the navigation for the flying boats only as far as Trepassey Bay.

The route, which started at Rockaway Naval Air Station and ended in Plymouth, England, would consist of six legs. The first leg was 540 nautical miles to Halifax. The second was 460 miles to Trepassey Bay, near St. Johns, Newfoundland. The third and longest leg of the Atlantic crossing would take the flying boats from Trepassey Bay to Horta in the Azores, a distance of 1,200 nautical miles. After a short hop of 150 miles to Ponta Delgada, also in the Azores, the crossing concluded with an 800-nautical-mile flight to Lisbon, Portugal. Finally, a 755-mile flight to Plymouth would end the journey.

Twenty-one ships were stationed along the flight path from Trepassey Bay to the Azores to aid in navigation and rescue if needed. A picket line of 14 ships was assigned from the Azores to Lisbon, and 10 ships from Lisbon to Plymouth. That sort of methodical planning and heavy investment — typical of the moon landings 50 years later — demonstrated the importance that the Navy placed on it. National prestige was at stake. In 1919, the main competition to be first across the Atlantic was the British. Before the Americans left Long Island, Australian test pilot Harry Hawker and his Scottish navigator Kenneth F. Mackenzie-Grieve, with their Sopwith Atlantic biplane, and F.P. Raynham and C.W.F. Morgan, with their Martinsyde Raymor, were already in Newfoundland. British Admiral Mark Kerr, with his Handley Page V/1500, and John Alcock and Arthur W. Brown, with their Vickers Vimy, were eager to jump into the fray. The British teams would attempt a flight from Newfoundland to the British Isles for a prize of 10,000 pounds sterling offered by the publisher of the Daily Mail, Alfred Harmsworth, Lord Northcliffe, for the first successful transatlantic flight.

On May 3, 1919, just two days after NC-4 made her first flight, the NC Seaplane Division was formally commissioned. NC-1, now equipped with four engines, would make her first flight in that configuration on the next day.

The operations were hindered by a series of accidents. On May 5 during fueling operations a fire broke out in the NC hangar, and NC-1‘s starboard wing was destroyed. But using the wing from the already cannibalized NC-2, it was soon repaired. Flares accidentally set off started another fire on May 6. After misjudging the distance to the aft propeller, Chief Machinist’s Mate E.H. Howard lost his hand on May 7.

Finally, on May 8, the Nancies left Rockaway for Newfoundland. NC-3 and NC-1 had relatively uneventful flights to Halifax, making the 540-nautical-mile trip in about nine hours. Along the way, however, cracks developed in the planes’ new, highly efficient Olmstead propellers. The Olmsteads were subsequently replaced with standard Navy propellers. NC-4, which was going through her shakedown flights on the way to Canada, was not so lucky. She lost both center engines and was forced to set down in the open sea near Cape Cod. The crew then taxied for five hours until the flying boat reached the naval air station at Chatham, Mass. Although NC-4 was repaired and ready to resume the flight by May 10, unfavorable weather delayed departure until May 14. NC-4 finally arrived in Halifax at 1:07 p.m. that day.

There was concern among NC-4‘s crewmen that if Towers received a favorable weather forecast, he would feel obliged to go for the Azores without them. Because of Howard’s accident and the plane’s failure to make Halifax, newspapers were calling NC-4 a ‘Lame Duck’ and circulating rumors that she would be withdrawn from the flight.

NC-1 and NC-3 had left Halifax for Trepassey Bay on May 10, but after their arrival weather conditions held up the flight’s continuance. Towers received a favorable weather report on the 15th and decided to go — without NC-4. Read actually witnessed them trying to take off as he arrived. But NC-3 and NC-1 were overloaded with fuel and could not get off the water. The weather forecast for the 16th was even better, and nobody had wanted to leave NC-4 behind. NC-4 was quickly overhauled, with mechanics installing one new engine and three propellers. On the evening of May 16, Towers gave the word to go. By then, the flying boats had traveled approximately 1,000 nautical miles (1,150 statute miles) from Long Island, but before them lay the featureless ocean. To guide their way they had only their primitive navigational instruments and, at night, a string of lights provided by the picket line of destroyers.

On Friday evening, May 16, the three NC flying boats roared in turn down Trepassey Harbor and flew off into the gathering darkness over the Atlantic. That night was without incident as the fliers passed over the destroyers on their ocean stations with reassuring regularity. Formation flying was difficult, since each airplane had its own flying characteristics and cruising speed: NC-4 was the fastest, NC-1 the slowest. After NC-3‘s lighting circuits failed during the night, the three planes were forced to break out of formation to avoid the risk of collision.

More troubles came with the onset of fog at dawn. In NC-3, Towers spotted a ship on the foggy horizon that he took to be one of the station destroyers and altered his course accordingly. Instead it was the cruiser Marblehead returning from Europe, and the mistake took NC-3 far off course. With fuel running low, Towers determined by dead reckoning that they were somewhere close to the Azores. He decided to put down long enough to obtain a navigation fix. The seas were running high, however, and the rough landing collapsed the struts supporting the centerline engines. In this condition NC-3 could go no farther — except as a surface craft.

Aboard NC-1, Bellinger was having similar difficulty. He landed without incident, but once down could not take off again through the 12-foot-high waves. Meanwhile Read, in NC-4, had also ‘run out of ships’ and was virtually lost in a fog that at one point was so thick the crew could not see from one end of the plane to the other. Losing sight of the horizon, the pilot became totally disoriented. He almost put the big plane into a spin, but recovered in time. However, Ensign Herbert Rodd, the radio officer, was successful in picking up radio bearings and weather information from the destroyers hidden below by fog and clouds.

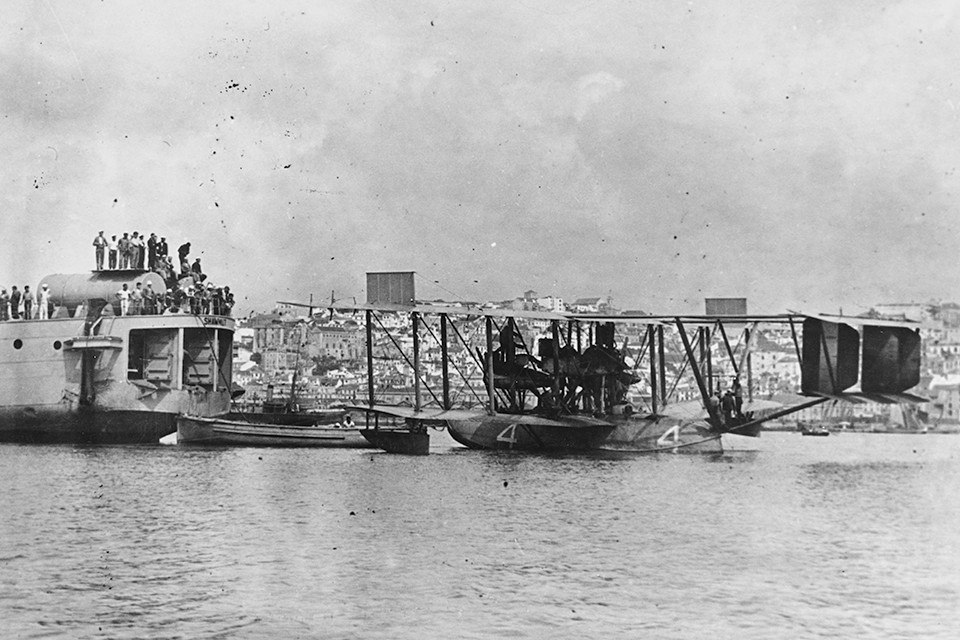

After more than 15 hours in the air, Read’s dead reckoning and Rodd’s radio reports indicated that NC-4 was very near the Azores. Suddenly, through a small break in the fog, they sighted Flores, one of the western islands of the Azores. With Flores as a checkpoint, Read swung NC-4 eastward toward the islands of Fayal and Sao Miguel, then settled for immediate safety on Fayal. NC-4 landed in Horta’s harbor a bit before noon. Within minutes of Read’s arrival, a great bank of fog had blotted out the port completely.

Upon boarding the cruiser Columbia, which was serving as the base ship for the NCs at Horta, Read and his men were quick to inquire about NC-3 and NC-1. They learned that NC-1, trapped and punished by the great waves, had been lucky to stay afloat. Fortunately, the Greek freighter Ionia rescued Bellinger and his crew, but NC-1 finally sank three days later.

The fate of NC-3 remained a mystery for 48 hours. Before leaving Trepassey, Towers, much to his dismay, had to tell Lieutenant L.C. Rhodes that he would need to stay behind in order to reduce weight for takeoff. Towers also jettisoned tools, a chair, extra drinking water and the emergency radio transmitter. Thus, NC-3 could receive radio calls but not send them. Pure seamanship had to take over. Towers figured that within two or three days he would drift close to Sao Miguel. On Monday afternoon, May 19, inhabitants of Ponta Delgada spotted the battered NC-3. When the destroyer Harding raced out to help, John Towers stood up and shouted, ‘Stand off! We’re going in under our own power.’ He and his crew had managed to sail their crippled plane 205 miles backward through violent seas, using the tail assembly as a sail.

With NC-4‘s arrival in the Azores, it was the British who panicked. Although NC-4 was not involved in the race for prize money, British honor was at stake. Hawker and Mackenzie-Grieve took off from Newfoundland and headed for Ireland on May 18. Less than halfway across they had consumed half of their gasoline. At dawn, with their radiator steaming, they had to ditch in the stormy North Atlantic.

Raynham and Morgan tried to take off about an hour after Hawker and Mackenzie-Grieve, but their Martinsyde could not lift off from the soggy field. They crashed in the attempt, and Morgan suffered permanent injuries.

For nearly three days NC-4 rode her moorings at Horta, kept there by high seas, rain and fog. On the 20th the weather cleared enough to permit takeoff, and in less than two hours NC-4 reached Ponta Delgada. Towers, who had arrived by sailing the last 205 miles, was already there to greet him. Despite Towers’ heroic achievement, NC-4‘s Commander Read was the popular hero. Navy Secretary Josephus Daniels gave orders for Towers to proceed onward by ship — he was forbidden to fly on NC-4 even as a passenger. It was a bitter pill for the division commander to swallow. Daniels, a former newsman, apparently thought it a better story that Read in his ‘Lame Duck’ had conquered the mighty Atlantic. NC-4 was scheduled to take off for Lisbon the next day, but weather and engine trouble delayed the departure for a week. While the crew waited, they learned that Hawker and Mackenzie-Grieve had been picked up by a Danish tramp steamer and had arrived safely in Scotland.

NC-4‘s crew was up before dawn on Tuesday, May 27. Lieutenant James L. Breese and Chief Machinist’s Mate Eugene S. Rhoads diligently pampered the plane’s engines. Herbert Rodd bestowed equal care on his indispensable radio set. (Much of the credit for the success of the entire NC-4 mission could be attributed to Rodd’s expert use of his radio and Read’s confidence in using his results.) At Read’s command, Lieutenant Elmer Stone advanced the throttles and sent the big flying boat charging down the harbor, then lifted off toward Lisbon.

Another chain of destroyers extended between the Azores and Lisbon. As NC-4 overflew the vessels, each ship radioed her passage to the base ship Melville at Ponta Delgada and the cruiser Rochester in Lisbon, which in turn reported to the Navy Department in Washington. Finally, word came from the destroyer McDougal, the last ship in the picket line, that NC-4 was within minutes of completing her historic flight.

In NC-4, the crew peered eastward, where the horizon was fading in the twilight of May 27. Then from the center of that darkening line there flashed a spark of light — Cabo da Roca lighthouse. They had sighted the westernmost point in Europe. Minutes later, NC-4 roared over the rocky coastline and turned south toward the Tagus estuary and Lisbon. According to Read, that moment was ‘perhaps the biggest thrill of the whole trip.’ Each man on board realized that no matter what happened — even if they crashed on landing — the first transatlantic flight in history was an accomplished fact.

After two days in Lisbon, where all three NC crews were honored by the Portuguese government, the NC-4 crew was ready to continue to Plymouth. NC-4 departed Lisbon on the morning of May 29, but a few hours later, near the Monedego River, she was forced down by engine trouble. The repairs took quite a while, and Read refused to risk landing in darkness at Plymouth. So NC-4 flew to Ferrol, Spain, for the night. The next day NC-4 completed the final leg of her flight, landing in Plymouth Harbor early in the afternoon of May 31, escorted by three flying boats of the Royal Air Force. She received a tumultuous reception from an English crowd.

During the 24-day duration of the nearly 4,000-mile flight, news of the flying boats’ progress was featured on the front page of most American newspapers. But other remarkable flights quickly followed. Alcock and Brown made the first nonstop Atlantic flight from St. Johns and crashed into a bog in Clifden, Ireland, in June 1919. Fearing that Admiral Kerr would overtake them, they put down as soon as possible to ensure that they would win the Daily Mail‘s cash prize. Eight years later, Charles Lindbergh completed his solo nonstop flight from Long Island to Paris. He was followed a month later by Clarence Chamberlin and then Richard E. Byrd.

By the time NC-4‘s crewmen arrived back in New York, in the days prior to ticker-tape parades, the only public acclaim they received was a private dinner thrown by Glenn Curtiss. The 1919 flight had highlighted the difficulties of flying the Atlantic. It would be 20 years before the lessons learned through the NCs’ flights were translated into regularly scheduled airline flights to Europe. On May 21, 1939, the Pan American Airways flying boat Yankee Clipper took off from Long Island and flew to Lisbon via the Azores. Six days later the airliner arrived back at Port Washington, exactly 20 years to the day after NC-4 had arrived in Lisbon.

Today if you take off from Long Island’s Kennedy Airport on your way to Europe, you may fly over Jacob Riis Park, former site of the Rockaway Naval Air Station. Eighty-three years ago three brave crews left that spot. By now, millions have flown across the Atlantic, but the honor of being first belongs to Lt. Cmdr. Albert C. Read, his crew of five and the U.S. Navy’s NC-4.

This article was written by Edward Magnani and originally published in the November 2002 issue of Aviation History.

For more great articles subscribe to Aviation History magazine today!