IN THE AUTUMN OF 1274, Kublai Khan, the Mongol emperor of China, dispatched hundreds of ships with an invasion force of tens of thousands to Hakata Bay, in western Japan about 100 miles from the Asian mainland. Vastly outnumbered and baffled by the invaders’ tactics—the Mongols attacked as units, while the samurai still fought as individuals—the Japanese gave up the beaches and retreated inland. The Mongolian forces returned to their ships for the night, confident of success the next day.

But that evening, a storm struck, dashing the ships against the rocks and killing about a third of the men. The Mongols withdrew, and the Japanese hailed the storm, unusual for that time of year, as a divine wind (kamikaze) sent by the gods to protect them.

Like The Spanish Armada, the Mongol fleets that invaded Japan in the 13th century are remembered largely for the disasters that befell them

In 1281, Kublai Khan tried again, dispatching a still larger force. Again, the Japanese were forced to retreat. A typhoon struck and for two days hurled Mongol ships against each other and the shore. The few that survived sailed away, leaving thousands of soldiers stranded. Once more, the Japanese celebrated a kamikaze that had saved them.

The only firsthand Japanese account of these two invasions survives in art form. The Mongolian Invasion Scrolls (Moko shurai ekotoba), commissioned by Takezaki Suenaga, a samurai warrior from Higo province in western Japan, are glorious paint-and-calligraphy renderings that, interestingly, make no mention of the storms. Instead, they document the valor and courage of the Japanese warrior—specifically, the very man who paid for them.

Takezaki Suenaga was a gokenin (houseman), a middle-ranking Japanese samurai. He apparently fought well in both invasions; he led small bands of his armed retainers against the Mongols, served under almost every high-ranking Japanese commander, and repeatedly put his life in danger.

Like other samurai of the period, Suenaga was concerned more with family alliances and honor than with nation. In true samurai fashion, he fought primarily for honor and the prizes of land and office. By his own account, he recklessly put himself in harm’s way in pursuit of accolades and glory.

Following the first invasion, Suenaga petitioned the military government (bakufu) to reward him for his service. He received land in the Higo province along with a horse. After the second invasion, Suenaga went to extraordinary lengths to document his exploits and honor his fellow samurai, commissioning two painted hand scrolls, or emaki.

Following the first invasion, Suenaga petitioned the military government (bakufu) to reward him for his service. He received land in the Higo province along with a horse. After the second invasion, Suenaga went to extraordinary lengths to document his exploits and honor his fellow samurai, commissioning two painted hand scrolls, or emaki.

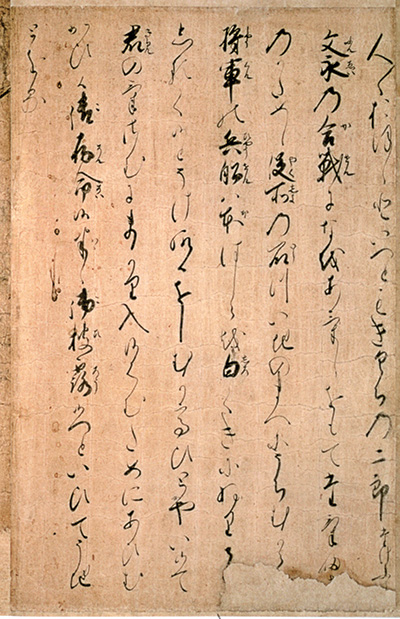

Often compared to comic strips or silent movie reels, emaki stretch dozens of feet long and combine painting with calligraphy to tell a story in a succession of scenes. They are meant to be read, not hung on the wall as decoration. The narrative runs from right to left, like Japanese script. Readers rest the scroll on a table, unrolling it with the left hand and rolling it up with the right as they move through the story.

Originally used to record Buddhist sutras and religious tales, emaki came to Japan with Buddhism in the eighth century. By the Mongol invasions, the art form was at its height. Generally commissioned by elites in big cities such as Kyoto and Kamakura, emaki featured literary works, folktales, quasi-historical accounts, military epics, and poetry. Artists abandoned the delicate painting style of earlier periods in Japan and relied on vivid colors, bold brush strokes, and an emphasis on plot, not emotion.

Each of the two scrolls commissioned by Suenaga alternates between text and painting. Someone other than the calligrapher (perhaps Suenaga) made notations in red ink to identify a character or correct an error in the depiction.

The work isn’t a historical record of the invasions—the focus is a single man’s actions—but it’s an invaluable portrait of the warriors, armor, and weapons of the era. Mongols appear in heavy coats belted at the waist and conical hats of felt and fur. Samurai wear boxlike armor (yoroi) with laminated leather scales, large shoulder plates, and neck guards. The detail is such that each leather scale is distinct. The Mongols carry composite crossbows and horsehair standards, while the Japanese wield long bamboo bows.

The first scroll, which is 80 feet long, depicts Suenaga’s actions during the Mongol invasion of 1274. It opens in western Japan with the samurai leading four armed retainers from Higo toward Akasaka, where Mongolian forces have landed. Though his commander orders Suenaga and his men to wait to launch a joint attack (probably with a band of 30 to 80 mounted warriors, most of them from his clan), the young samurai chafes at the delay.

“Waiting for the general will cause us to be late to battle,” he says. “Of all the warriors of the clan, I, Suenaga, will be first to fight from Higo.”

With that, Suenaga charges on horseback through the landscape with his men, advancing across each scene in the scroll from right to left, toward the enemy. When the Mongols appear, they move from left to right, a deviation from the emaki’s traditional flow of movement that underscores their role as invaders. Samurai and Mongols alike are disproportionately large in relation to their surroundings—an emaki convention. The landscape is sketchily drawn, but the faces, armor, and weaponry of warriors on both sides are presented in realistic detail. Arrows fly, horses gallop, banners wave. Japanese soldiers carry Mongol heads impaled on pikes, and Korean foot soldiers take cover behind distinctive woven bamboo shields.

In the most famous scene, a bomb explodes next to Suenaga and his horse—perhaps the first depiction of the use of gunpowder in war, although some scholars suggest the bomb was added to the scrolls in the 18th century. Both the warrior and his animal have already suffered arrow wounds, and their blood is pouring to the ground. War in these scenes is stylized, but never idealized.

ACTION COMES TO A HALT in the second half of the scroll as Suenaga cools his heels in Kamakura, working his way through 13th-century Japan’s version of Catch-22 as he navigates the bureaucracy to lobby for his reward. Time and again, he visits officials to plead his case. These scenes are static and set in carefully delineated interiors painted from a high angle that distances the viewer. There is no movement. With the exception of Suenaga, everyone is seated, even two samurai, who doze over curved swords. Action returns only in the final scene, when Suenaga receives a spirited horse in recognition of his war service.

The second scroll, extending 69 feet, tells of Suenaga’s deeds in the 1281 invasion. Painted in the rich reds and blacks used in the earlier battle segments, these scenes are more tightly packed. At first, warriors await the arrival of the Mongols—shoulder to shoulder behind defensive walls the Japanese had built in anticipation of a second invasion. Suenaga and a few others are so eager to fight that they position themselves in front of the walls, defying danger.

Soon the scene shifts to a Japanese attack on the Mongol fleet. The scroll fills with crowded boats and choppy water. Suenaga goes from boat to boat, trying to lie or force his way on board so he can fight and seize more glory. Having finally secured a place, he finds he has left his helmet behind and fashions one from another soldier’s shin guards. The action ends with the Japanese boarding a Mongol ship and Suenaga arriving safely on shore.

The famous “divine winds” do not appear in Suenaga’s account of either invasion. We know of them from Mongol chronicles, which cited the storms as an explanation for their defeat, and claims by Japanese temples that their priests’ prayers had protected Japan from invasion. The winds remained an important part of Japanese political mythology as late as World War II, when suicide bombers took the name kamikaze to symbolize their own role protecting the nation.

And Takezaki Suenaga? He slipped into obscurity until the late 18th century, when scholars rediscovered his scrolls. Five hundred years after his death, Japan built a shrine and two monuments honoring Suenaga as a national hero, the personification of a Japan unconquered by foreign invaders. His scrolls had done their work.

Pamela D. Toler is a freelance writer with a doctorate in history and an interest in the times and places where two cultures meet and change each other. She is the author of Mankind: The Story of All of Us.