On August 5, 1964, aircraft from the USS Constellation and Ticonderoga struck the North Vietnamese fuel depot at Vinh and three enemy PT boat bases. Designated Operation Pierce Arrow, the strikes were in retaliation for PT boat attacks on U.S. naval forces operating off North Vietnam on August 2 and an alleged attack that never did happen on August 4.

This was the “Gulf of Tonkin Incident” that triggered the United States’ massive involvement in the Vietnam War. Poststrike reconnaissance indicated that the 67-plane raid had severely damaged the fuel depot, sunk seven North Vietnamese PT boats and damaged 26 others. Two U.S. Navy planes were shot down. One of them was a Douglas A-1 Skyraider piloted by Lieutenant Richard Sather, who was killed. The other, a Douglas A-4C Skyhawk piloted by Lieutenant Everett Alvarez, suffered critical damage from North Vietnamese light anti-aircraft fire, but Alvarez managed to eject successfully and was captured, becoming the first American prisoner of war in North Vietnam.

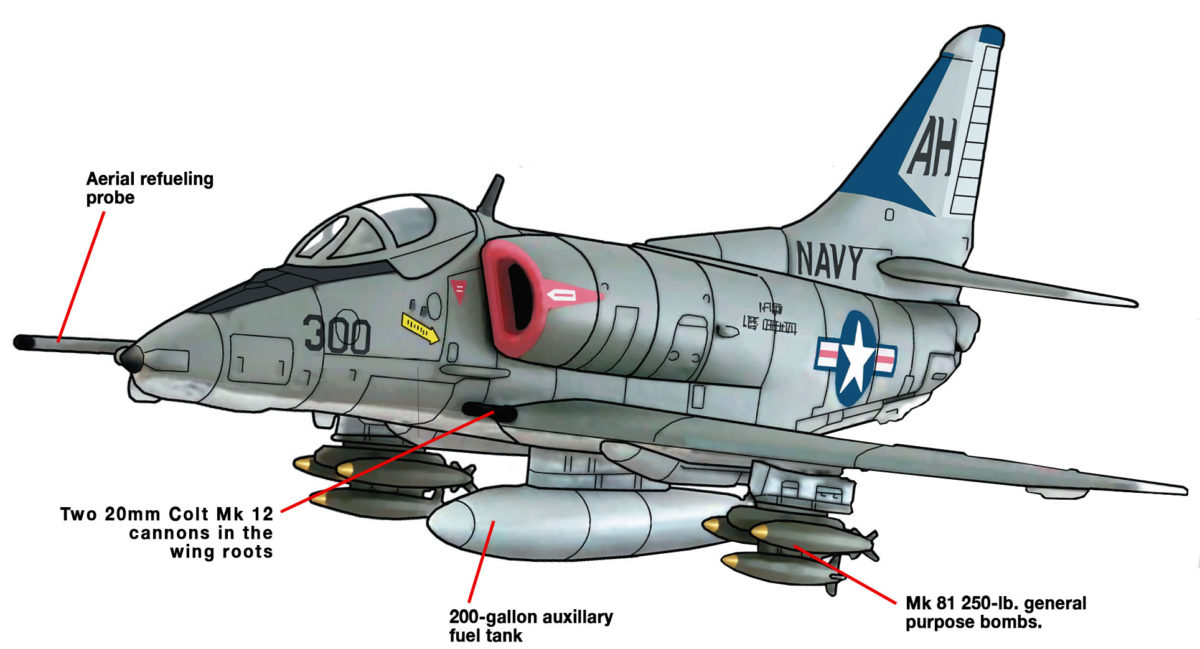

The A-4C Skyhawk, from the first shots to the end, proved to be the Navy’s most used attack aircraft in the Vietnam War.

Designed in late 1951 to replace the Navy’s piston-engine A-1 Skyraider, at a time when nuclear massive retaliation was the national doctrine, the A-4’s specifications called for a light, expendable aircraft capable of carrying a single 2,000-pound bomb to a target 300 nautical miles away at a maximum speed of 500 knots (520 mph). The plane’s maximum permissible weight was 30,000 pounds. The Douglas team, headed by Edward H. Heinemann, promised Navy officials it could meet the specifications—in a plane that didn’t exceed 15,000 pounds fully loaded. Moreover, the designers said their plane would be 90 knots (96 mph) faster, carry twice the bombload and have three times the range of its predecessor. Few believed the claims, but the Navy’s chief of the Bureau of Aeronautics, Rear Adm. Apollo Soucek, approved the design and awarded a contract for two prototypes, designated the XA4D-1, in July 1952. The order was increased to 19 in October.

Saving weight became the design team’s guiding tenet. Wingspan was to remain within the dimensions of the Essex-class carrier’s elevators, eliminating the then-traditional carrier aircraft wingfold. That saved 200 pounds and reduced maintenance requirements. The designers visited several aircraft carriers and three Marine Corps airfields to observe the two services’ jet aircraft arming and fueling operations. They interviewed jet fighter pilots and piston-engine attack pilots. They then incorporated the resulting lessons learned and “insights from the field” into key elements of the new plane’s design. The cockpit and canopy were shaped so as to have the pilot see the plane as an extension of himself. Despite all this care, the early instrument panel design was severely criticized when the plane entered service, and it had to be completely redesigned from the third production batch onward.

The XA4D-1 started its test flight program on June 22, 1954. The plane’s engine was a Wright J65, a license-built version of the British Armstrong Siddeley Sapphire turbojet used in the Hawker Hunter fighter. Its maximum rated thrust was 8,300 pounds, which should have given the XA4D-1 a thrust-to-weight ratio of 0.56:1 in fully loaded condition, only slightly less than that of the MiG-17, the latest Soviet fighter, which was about to enter production later the same year. In practice, however, the American-made engines provided a little more than 7,000 pounds of thrust, cutting the thrust-to-weight ratio down to 0.48:1. Some had argued for the Pratt & Whitney J57 engine because of its higher thrust of 11,600 pounds, but the J57 weighed nearly twice as much as the J65. More important, its far greater dimensions would have necessitated a larger fuselage with a corresponding increase in aircraft weight, dimensions and cost. Despite the lower engine thrust, the A-4 briefly held the 500km speed record with a speed exceeding 695mph, besting that of the F-86H. This marked the first time an attack aircraft had set the record, earning it the sobriquet “Heinemann’s Hot Rod.”

The A4D-1 entered service with Attack Squadron 72 (VA-72) in August 1956 and with VA-93 three months later. The Navy’s training or replacement air groups (RAGs) didn’t receive their first A4D-1s until 1958. The improved A4D-2, with an in-flight refueling probe, was introduced in 1959. The next change came in July 1962, when Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara directed the services to adopt a common naming and designation system. Under that system, the A4D-1 became the A-4A and the D-2 became the A-4B in October 1962. The addition of a simple terrain radar and other avionics improvements, including a redesigned instrument panel, resulted in the A-4C, which entered service that same fall. The Skyhawk encountered some early problems. Spare parts, particularly for the engine, always seemed to be in short supply. In addition to diminished thrust performance, the J65 engine suffered from a periodic stuck-throttle problem. If the engine was left in a cruise power setting (35-40 percent of full power) for prolonged periods, the pilot couldn’t increase power beyond that point. That led to accidents during carrier landings when the pilot couldn’t accelerate back into the air after he “missed the wire.”

The problem was solved in the A-4E with the introduction of the Pratt and Whitney J52-P6A engine, which weighed 700 pounds less and provided more than 2,300 pounds additional thrust. Its fuel consumption, particularly at cruise settings, was significantly better as well. The engine’s greater length (9 inches) and increased power, however, required the fuselage to be lengthened 14 inches and the wing spars reinforced. Maximum bomb load was increased to nearly 6,000 pounds, and despite the 2,000-pound increase in maximum takeoff weight, the plane’s thrust-to-weight ratio was improved to 0.58:1. The A-4E joined the fleet in January 1963.

The A-4C was the dominant Skyhawk variant in service when the United States entered the Vietnam War. It was a nimble little plane with a limited radar cross section, making it ideal for light attack and nuclear strike missions. The U.S. Navy’s expected Cold War opponents, the Soviet and Chinese navies, were low-tech fleets with limited radar and electronic capabilities. As a result, the Navy leadership had no experience with and saw no need for tactical electronic-countermeasures equipment. Only its surveillance, airborne early warning and intelligence-collection aircraft had electronic sensing, warning and countermeasures equipment. That changed with the 1965 introduction of Soviet-built SA-2 Guideline surface-to-air missiles (SAMs) into North Vietnam.

Flying a plane without radar-warning systems, A-4 pilots had to rely on the timely sighting of an SA-2 launch to survive a SAM engagement. At first, pilots and leaders placed their faith in low-level approach tactics that reduced enemy warning time and placed the Skyhawks below the SA-2’s minimum altitude. By 1966, however, North Vietnam had more than 7,000 antiaircraft guns of all calibers spread out across the country and in concentrations around expected targets. Some of the guns were radar-controlled, but predictable U.S. tactics enabled the North Vietnamese to use concentrated box barrage tactics, in which the gunners filled the sky with steel between the target and the pilot’s roll-in point.

The A-4’s tightly compact airframe now worked against it. There wasn’t any available room in the fuselage to install new avionics and electronic warfare equipment. Moreover, the plane’s limited wingspan could accommodate only two wing stations, forcing the plane to be configured either for bombing or carrying electronic counter measures equipment. As a solution, the designers added a fuselage “hump” behind the cockpit, filling it with new navigation, night flying and, most important of all, radar warning and electronic countermeasures (ECM) equipment—the AN/ALR-50 SAM alert system and AN/ALQ-126 defensive ECM system. The new avionics package was developed and installed on new production aircraft within 90 days. A-4Es already in service had the “hump” installed when the aircraft returned from deployment. The introduction of the ALQ-100 deceptive jamming equipment in an under-nose fairing and wing spoilers marked the A-4F. Some had the AN/ALR-45 radar warning system antenna installed in a fin-tip extension. Approximately 100 of those were equipped with the J52-P408 engines that provided 11,200 pounds of thrust. Designated the “Super Fox,” this variant is renowned for its service with the Navy’s Blue Angels.

By war’s end, the A-4 was the most numerous attack aircraft in the U.S. Navy’s inventory. Losses in Vietnam totaled 384 Navy and Marine Skyhawks from all causes—36 percent of those used by both services—179 of which were over North Vietnam. Only one was confirmed to have been shot down by enemy aircraft—on April 25, 1967, Lt. Cmdr. Charles D. Stackhouse of VA-76 ejecting to become a POW—even though North Vietnam’s MiG-17 pilots stated they favored the A-4 as a target because it lacked the speed to escape an intercept. Remarkably, during a low-level dogfight on May 1, 1967, Lt. Cmdr. T. R. Swartz of VA-76 avenged Stackhouse when he brought down a MiG-17, with an unguided Zuni air-to-ground missile!

Despite its successes, low cost and tactical advantages, by 1970 it was obvious that the A-4’s airframe had reached the limit of its potential for future growth. The A-7 Corsair II had greater range, carried a heavier payload and could more easily accommodate the new electronic warfare, radar and navigation systems that were becoming essential to modern naval strike warfare.

Still, the lightweight A-4’s economical and agile operation made it a popular aircraft for a wide variety of other roles. More than 60 were transferred to Israel in 1971, where they served in the fighter-bomber role during the 1973 Yom Kippur War and over Lebanon in the early 1980s. The A-4 and its later variants saw widespread service elsewhere around the world, including in Operation Desert Storm in 1991. At a flyaway cost of less than $1 million a copy, the A-4 proved one of the best military bargains of the Cold War era.

Originally published in the June 2008 issue of Vietnam Magazine. To subscribe, click here.