Information about The Battle & Surrender At Appomattox Courthouse, one of the last Civil War Battles of the American Civil War

Appomattox Courthouse Battle Facts

Location: Appomattox Courthouse, Virginia

Dates: April 9, 1865

Generals: Union: Ulysses S. Grant | Confederate: Robert E. Lee

Soldiers Engaged: Union Army: 120,000 | Confederate Army: 30,000

Outcome: Union Victory

Casualties: Union: 260 | Confederate: 440; over 27,000 surrendered

Appomattox Court House Battle Summary: The Battle of Appomattox Courthouse was the Army of Northern Virginia’s final battle and was the beginning of the end of the American Civil War. Though the actual battle took place on April 9, 1865, it followed the 10-month Battle of Petersburg and concluded General Robert E. Lee’s thwarted retreat during the Appomattox Campaign.

After a long night and day of marching, Lee and the exhausted Army of Northern Virginia made camp just east of Appomattox Courthouse on April 8. Lieutenant General Ulysses S. Grant had sent him a letter on the night of April 7, following confrontations between their troops at Cumberland Church and Farmville, suggesting Lee surrender. The Southern general refused. Grant replied, again suggesting surrender to end the bloodshed. Lee responded, saying in part, "I do not think the emergency has arisen to call for the surrender of this army," though he offered to meet Grant at 10 the next morning between picket lines to discuss a peaceful outcome.

In planning for the next day, Lee informed his men that he would ignore the surrender request and attempt to fend off Sheridan’s cavalry while at least part of the Army of Northern Virginia moved on toward Lynchburg—assuming the main Union force was just cavalry. However, he asked to be informed if his men encountered any infantry, since that would mean he was outnumbered and would be forced to surrender.

Grant had spent the last week pursuing and closing in on Lee during the Appomattox Campaign. On the north side of the Appomattox River, Major General George G. Meade’s VI and II Corps were in close pursuit of Lee’s beleaguered army, while Maj. Gen. Philip H. Sheridan’s cavalry had taken a southern route to outrun Lee and surround him on the west and south.

Early in the morning on April 9, Confederate maj. gen. John B. Gordon’s corps attacked the Union cavalry blocking the road toward the railroad. Initially, Gordon had success in clearing cavalry from the road, but Union infantry moved in and he was unable to make further progress. Gordon sent word to Lee around 8:30 a.m. that he needed Lt. Gen. James Longstreet’s support to make additional headway.

Upon receiving this request—and having watched the battle through field glasses—Lee then said, "Then there is nothing left for me to do but go and see General Grant, and I would rather die a thousand deaths." Having dressed that morning in his finest dress uniform, Lee rode to the spot where he thought he and Grant would be meeting between the picket lines. There, he received Grant’s message, written the night before, in which Grant refused to meet to meet for peace talks.

Lee quickly wrote a reply, indicating that he was now ready to surrender, and rode on. Still hearing the sounds of fighting, Lee sent a letter to Meade requesting an immediate truce along the lines. Meade replied that he was not in communication with Grant but would send the message on and also suggested Lee send another letter to Grant via Sheridan. In addition, Lee also had Gordon place flags of truce along the line. As the messages moved through the lines and word of the surrender spread, the fighting stopped. Casualties for the Battle of Appomattox Courthouse were light, 260 for the Union, 440 for the Confederacy.

Grant received Lee’s letter of surrender just before noon. He replied, detailing his current position along the road toward Appomattox Courthouse, and asked Lee to select a meeting place.

Lee and his men, in searching for a suitable place to have the surrender meeting, encountered Wilmer McLean, who showed them an empty building without any furniture. When that was deemed unsuitable, he offered his own home for the meeting. It is interesting to note that McLean had moved to Appomattox after having survived the First Battle of Bull Run, much of which took place on his property in Manassas, Virginia. It is often said that the war started in his front yard and ended in his parlor, though that is not accurate.

Grant arrived in Appomattox at about 1:30 in the afternoon and proceeded to the McLean house. His appearance in his field uniform, muddy after his long ride, contrasted sharply with Lee’s clean dress uniform. They chatted for a while before discussing and writing up the terms of the surrender.

The soldiers of the Army of Northern Virginia would lay down their weapons and not take them up against the U.S. government again. Soldiers would be paroled and allowed to return home instead of being imprisoned. All Confederate equipment would be relinquished and inventoried. They agreed that any Confederate who claimed to own a horse or mule and would need it for spring planting would be allowed to keep it. Lee also requested rations for his men, as it had been several days since they had eaten, and Grant then agreed to provide them. After formal copies of the surrender document were made and the document signed, they parted. After such a long, bloody war and a particularly grim retreat, the surrender of the Army of Northern Virginia has been referred to as "The Gentlemen’s Agreement," a testament to the character of these two great men.

Upon hearing the sounds of Union soldiers celebrating the surrender by firing salutes, Grant instructed that his troops cease active celebration, saying, "The war is over; the Rebels are our countrymen again, and the best sign of rejoicing after the victory will be to abstain from all demonstrations in the field." This set the tone of the next few days, including the formal surrender ceremony that occurred April 12. Brigadier General (brevetted major general) Joshua L. Chamberlain, who had won renown at Little Round Top during the Battle of Gettysburg, was charged with officiating at the surrender ceremony at Appomattox Courthouse. He ordered his subordinate officers to come to the position of "carry arms," and on the approach of each body of troops from the Army of Northern Virginia, a bugle sounded and his men saluted. The Confederates saluted back in response and laid down their arms and colors. The formal ceremony, which saw the surrender of over 27,800 men, took nearly the entire day.

Although Lee surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia, the war was not over. There were still Confederate armies in the field and the final battle of the war would not happen until in May 12–13 in south Texas, at the battle of Palmito (Palmetto) Ranch near Brownsville. However, Confederate commanders did begin to surrender as news of the Army of Northern Virginia’s surrender spread.

On April 26, Gen. Joseph E. Johnston surrendered to Gen. William T. Sherman near Durham, North Carolina. Initially, in a meeting on April 17, Sherman offered terms even more generous than those given by Grant, but on April 14 President Abraham Lincoln was assassinated, dying the next day, and the North was not feeling magnanimous. Sherman had to return to Johnston on the 26th with new terms. Johnston, ignoring a direct order from Confederate president Jefferson Davis, surrendered all troops in the Carolinas, Georgia, and Florida.

On May 4, Lt. Gen. Richard Taylor surrendered at Citronelle, Alabama. May 10, Confederate President Jefferson Davis was captured with his wife at Irwinville, GA.

In New Orleans on May 26, Lt. Gen. Simon Bolivar Buckner, acting on the authority of Gen. Edmund Kirby Smith, commander of the Trans-Mississippi Department, accepted from Maj. Gen. Edward R. Canby the same surrender terms as Lee, Johnston, and Taylor. Ironically, Buckner had been forced to surrender the first Confederate army captured by the Union when his commanders abandoned him following the Battle of Fort Donelson in February 1862. After Buckner and Canby reached their agreement, a document was prepared and sent to Galveston, Texas, where Smith attached his signature on June 2, officially surrendering the last significant Confederate force.

Not until June 23 did Brig. Gen. Stand Watie surrender his small force of Confederate Cherokees in Oklahoma. The final act would come November 6, when the ocean raider CSS Shenandoah struck her Confederate colors in Liverpool, England.

Articles Featuring Appomattox Court House Battle From History Net Magazines

Featured Article

America’s Civil War: Images of Peace at Appomattox

No one knows for certain how the myth was born. But no one can deny that it was enduringly appealing and slow to die. As Ulysses S. Grant would put it years later, ‘like many other stories, it would be very good if it was only true.

The legend was that on April 9, 1865, Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered to Lt. Gen. Grant, not inside the McLean House in Appomattox Court House, Va., but outdoors, in an apple orchard somewhere outside the village. It was a romantic story, conjuring up a picture of rival commanders on horseback solemnly stacking their arms before opposing lines of blue and gray. It was also entirely false.

Nonetheless, throughout the mid-1860s the tale of the apple orchard surrender was repeatedly introduced, colorfully illustrated and widely distributed to an accepting public by the nation’s most imaginative purveyors of popular culture: the publishers of popular prints. To America’s engravers and lithographers falls the dubious honor of having perpetuated the myth by vivifying it in a seldom-remembered body of gaudy prints for American parlors, taverns and clubhouses.

In the years before the advent of motion pictures, radio and TV, picture publishers had considerable power, coloring public perception of the events of the day. Illustrations forged images of the news and the newsmakers — whether realistically depicted or not — into the collective consciousness of the national audience. So it was with the Appomattox story.

But how did the apple orchard surrender tale get started? As Grant conceded, it was one of those little fictions based on a slight foundation of fact. And it was reinforced by an incidental but much-noticed follow-up to the historic surrender.

As memoir writers on both sides of the Civil War would later recount, Confederate forces were actually occupying a hillside that embraced an apple grove on April 9, 1865. Grant related in his memoirs how a dirt road ran diagonally up that hillside, and how so many Rebel supply wagons had traveled the trail that their wheels had cut through the protruding roots of an apple tree, creating a makeshift embankment along the supply route. It was on this embankment, Grant was told, that his Confederate counterpart was sitting, his back against an apple tree, when he finally decided the time had come to surrender the Army of Northern Virginia.

Union Brevet Brig. Gen. Horace Porter recalled a similar scene. Porter wrote that Lee was lying down by the roadside on a blanket which had been spread over a few fence rails on the ground under an apple-tree, which was part of an orchard.

|

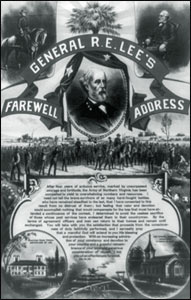

| Reverence for the iconic Robert E. Lee continued for many years after his death in 1870. Charles Walker’s 1893 lithograph commemorates the general’s simple and heartfelt farewell to his troops: You will take with you the satisfaction that proceeds from the consciousness of duty faithfully performed, and I earnestly pray that a merciful God will extend to you His blessing and protection (Library of Congress). |

Not surprisingly, Confederate writers chose to present a more active Lee: not a broken man lying on the ground, accepting the inevitable, but a mass of energy and resolve, resisting overwhelming forces until he wisely perceived the futility of struggling on. Colonel William W. Blackford, who had been an aide to Confederate Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart until the general’s death in May 1864, was present at Appomattox. He remembered an apple orchard guarded by a line of sentinels, where Lee could be found on surrender day pacing backwards and forwards…looking like a caged lion.

Blackford’s recollection was of a Lee quite unlike the idealized character later immortalized in popular prints and literature. To be sure, the general was the embodiment of all that was grand and noble in man in his full-dress uniform, complete with sword and sash. But he was also in one of his savage moods, Blackford remembered, and when these moods were on him, it was safer to keep out of his way. Lee that day was anything but the oft-portrayed stoic, dignified commander, made still more dignified by his gallantry in defeat.

Lee had good reason to fume, according to his aide, Colonel Charles Marshall. On April 8, wrote Marshall, Lee had proposed meeting Grant on the old stage road to Richmond, between the picket lines of the two armies, to discuss not surrender but peace. Grant made no reply to the invitation, but the next morning, Lee and two of his officers rode under a flag of truce toward the specified rendezvous. The men in the last hours of the Confederacy cheered General Lee to the echo, Colonel Marshall remembered, as they had cheered him many a time before. He waved his hand to suppress the cheering, because he was afraid the sound might attract the ire of the enemy, and we rode on through the line.

To Lee’s disappointment, Grant never showed up. Instead, a Union staff officer delivered a note Grant had written to Lee. Grant had no authority to discuss the subject of peace, it said, only surrender. Marshall read the letter to Lee, and after a few moments’ reflection, the Confederate commander made his most difficult decision. Well, write a letter to General Grant, he told Marshall, and ask him to meet me to deal with the question of the surrender of my army.

Even though Grant refused to meet Lee on the morning of April 9, at least one printmaker immortalized the event-that-never-was with a large lithograph of the Meeting of Generals Grant and Lee Prepatory to the Surrender of General Lee. Nearly a year would pass between surrender day and the publication of the print. But for artist P.S. Duval of Philadelphia and his publisher, Joseph Hoover (both experienced professionals who by then surely knew better), the dramatic appeal of the ride along the old stage road must have seemed irresistible.

What happened after Lee sent his message to Grant has been confirmed by memoirists of both North and South. The best account is probably that of Marshall, who was dispatched to Appomattox to find a place suitable for the surrender meeting. There, he encountered Wilmer McLean, a man…who used to live on the first battle field of Manassas, at a house about a mile from the Manassas Junction. He didn’t like the war, and having seen the first battle of Manassas, he thought he would get away where there wouldn’t be any more fighting.

In the end, the man who didn’t like the war provided the place to end it — not as he first suggested, at a nearby home that Marshall thought all dilapidated, but in his own very comfortable house. Within minutes, in the 20-by-16 1/2-foot McLean parlor, Robert E. Lee surrendered his army to Ulysses S. Grant.

Lee arrived first, looking to one observer quite bald and wearing one of the side locks of his hair thrown across the upper portion of his forehead, which is as white and as fair as a woman’s. Nonetheless, to his aide Armistead L. Long, even vanquished, Lee was yet a victor….Under the accumulation of difficulties his courage seemed to expand…his presence inspired the weak and weary with renewed energy….Those who watched his face to catch a glimpse of what was passing in his mind could gather thence no trace of his inner sentiments.

His image stands out clearly before me, Long wrote years later. Just after he had signed the surrender papers and emerged from the McLean House, Lee suddenly seemed to Long older, grayer, more quiet and reserved…very tired. But he would not be so portrayed.

|

| The orchard myth was a popular subject for printmakers. P.S. Duval’s orchard scene is an early example of the myth in print. (Library of Congress). |

Northern printmakers were the only such artisans to produce Appomattox surrender scenes. They also produced most of the portraits of Lee, Confederate Lt. Gen. Thomas J. Stonewall Jackson and Confederate President Jefferson Davis in the postwar era. But they were not aggressive researchers. Many searched no further for contemporary descriptions of Lee’s appearance at Appomattox than the New York Herald’s report of April 14: Lee looked very much jaded and worn, but nevertheless, presented the same magnificent physique for which he had always been noted….During the whole interview he was retired and dignified to a degree bordering on taciturnity, but was free from all exhibition of temper or mortification. His demeanor was that of a thoroughly possessed gentleman who had a very disagreeable duty to perform, but was determined to get through it as well and as soon as he could.

Grant, who arrived after Lee, looked to one witness as though he had had a pretty bad time. He came dressed in a sack coat and a loose fatigue blouse. In sharp contrast to Lee’s glorious new full-dress uniform, Grant wore no side arms: Lee wore his magnificent gold-handled ceremonial sword. Grant appeared somewhat dusty and a little soiled. Lee was impeccable and grand, now and forever the perfect knight of legend, exuding gallantry in defeat. The simple truth was that Grant had garbed himself in what he called a rough traveling suit, the uniform of a private with the stripes of a Lieutenant-General, because his own stock of fancy uniforms had not yet arrived at his headquarters. This ironic contrast between the simplicity of the victor and the grandeur of the vanquished would be pointedly reflected in many prints of Appomattox and would grow into a legend in American history.

The events inside the McLean parlor were formal and unemotional. After some conversation, Lee asked Grant to put his surrender terms in writing. Grant’s aide, Colonel Ely S. Parker, brought a small table from one corner of the room, and Grant sat down and wrote out the conditions of surrender on field note paper, which produced a copy as the original was written. When he finished, Grant rose and carried his draft to Lee, who remained seated elsewhere in the parlor. Lee offered some comments, including his well-known appeal that his soldiers be allowed to keep their horses, a request to which Grant consented immediately. Grant then asked Colonel Parker to recopy the terms of surrender. Parker took the desk to a far corner of the room and began to rewrite the official document while Grant took another seat and, like Lee, waited patiently. Other officers in the room, including Marshall and Union Maj. Gen. Philip Sheridan, exchanged pleasantries while they waited.

When Parker finished his transcription, Colonel Marshall took his seat to write out Lee’s reply. The general admonished his aide not to begin the answer in the customary way. I have the honor to acknowledge the receipt…. Don’t say, `I have the honor,’ said Lee. Just say, `I accept these terms.’

Finally the surrender papers were signed by both generals, their aides handing them separate copies and then exchanging them so each commander could sign two. After a few more moments of conversation, during which Grant finally explained why he wore a field uniform that was no match for his rival’s, Lee left the McLean House.

Such was the history of the surrender of Robert E. Lee’s army. There was no theatrical display about it, Marshall observed. It was in itself perhaps the greatest tragedy that ever occurred in the history of the world, but it was the simplest, plainest, and most thoroughly devoid of any attempt at effect, that you can imagine.

But Marshall did not realize what could be imagined by America’s printmakers. Besides, the story had not really ended. There was to be a dramatic coda that would add another layer of confusion to the surrender story.

|

| Wilmer McLean, owner of the house where the surrender was signed, commissioned this print as a way to raise money to pay for property damage that occurred during the war. Lee is accompanied by two aides, while Grant is surrounded by the cream of the Union officer corps, including George Custer, Philip Sheridan, George Meade and Edward Ord. McLean’s hopes for restitution were in vain; he abandoned the property in 1867, and the house was sold at public auction two years later (Library of Congress). |

The Lee of legend (and popular illustrations) had already been created by the time the generals returned from the true site of the surrender ceremony. All along his route, he was hailed with such cries as I love you just as well as ever, General by his loyal, tearful troops. Though truly a fine and noble man, Lee had become even more: the gallant cavalier who bravely fought a war he had not sought, and who surrendered with all the grace of a gentleman, though he had confided he would rather die a thousand deaths than do so.

The day after the surrender, Grant declared, I would like to see General Lee again. This time they did meet on horseback, chatting for half an hour near the old Confederate headquarters as staff officers hovered nearby. It was an incidental meeting, an anticlimactic footnote to the historic day that preceded it. But it seems that stories of this second encounter stimulated a lingering belief that Lee actually surrendered in such a setting.

Had the printmakers supplied Appomattox scenes more quickly, the legend might never have grown. Only two printmakers issued Appomattox scenes in 1865, and both erred, if at all, on the side of understatement. Most depictions were delayed until 1866 or 1867. So it remains one of the great mysteries of Civil War iconography why such a newsworthy event was not portrayed more quickly. Perhaps time was needed for passions to cool, and for Northern calls for Lee’s punishment to quiet down. It may be that some months had to pass before any Northern engraver or lithographer could feel safe portraying former enemy Robert E. Lee, even in defeat.

Southern printmakers provided no Appomattox scenes. They had been all but ruined by the war, driven out of business by chronic shortages of paper and ink, or compelled to focus on official work such as Confederate postage stamps and currency. By the time the war ended, the Southern print industry was, for all intents and purposes, a memory. And even had it survived, bitter recollections of Lee’s surrender and scenes of Appomattox would not have appealed to its customers.

Northern printmakers, denied access to the Southern audience for four years, gradually began supplying the images of the Lost Cause that they could never have been produced while the cause lived. During the late 1860s and throughout the ’70s and ’80s, parlor portraits of the principal heroes of the Confederate experience — Lee, Jackson and Davis — would be published by men in New York, Philadelphia, Boston and Chicago, men who had been enemies of the South just a few years earlier.

The appearance of these portraits and the first engravings and lithographs of Lee’s surrender signaled the beginning of the Northern effort to portray the Confederate image for profit. But along with the opportunities for profit came a challenge. It seemed difficult to market accurate prints of a surrender that was so simple and set in such mundane surroundings. Most solved this dilemma by providing imagined scenes of the purported apple orchard peace conference.

Among the more common orchard peace conference pictures, one of the most typical is the overdramatically titled Capitulation and Surrender of Robt. E. Lee & His Army at Appomattox. More restrained efforts are described as scenes of the Grant and Lee meeting, but their implicit message is the same: They are meant to suggest the actual surrender.

Lee actually returned to the orchard after signing the peace terms, and stood under an apple tree for the rest of the afternoon seeing visitors. After the soldiers left, Colonel Blackford remembered, the tree General Lee stood under was carried off by relic hunters. But print audiences had no reason to be concerned about this vandalism. For months afterward, the legendary tree would appear and reappear in purported re-creations of a scene that had never taken place.

In James Queen’s 1866 lithograph, Lee is shown reading the surrender terms beneath the ubiquitous apple tree while Grant gestures grandly to the rival armies encamped in the distance. The portraits of the generals are excellent; the setting is pure invention.

Another effort, by Philadelphia’s Joseph Hoover, makes Lee appear almost eager to surrender, reaching out for the terms in Grant’s hand. Again the scene is outdoors, and to add to the mythicizing, both Lee and Grant are shown in resplendent fancy dress uniforms, Grant wearing a sword, something he rarely did anywhere. Still another outdoor interpretation suggests that the surrender occurred in winter, an error arising perhaps out of ignorance, perhaps to emphasize the hardships the soldiers had suffered. Two other prints, one likely copied from the other, contend that Grant handed the surrender terms to Lee.

But no popular print of the apple orchard surrender exaggerated quite as grandiosely as Kurz & Allison’s lithograph of the Capitulation and Surrender of Robt. E. Lee & His Army. The symbolic scene shows both Union and Confederate armies crowded into the orchard, actually meeting en masse for the surrender. Stereotypically tattered and wounded Confederates on one side of the scene are contrasted with hearty-looking Union troops behind Grant. To add to the absurdity of the picture, Lee is shown publicly surrendering his sword to Grant. Grant later characterized the much talked of surrender of Lee’s sword and my handing it back as the purest romance. To printmakers such as Chicago’s audience-wise Louis Kurz, though, truth was not the test of a good picture; sales appeal was.

Currier & Ives’ two straightforward Appomattox lithographs were exceptions. But the work of these celebrated New York printmakers was not devoid of inaccuracy. Both their 1865 and 1873 prints depict Grant and Lee sharing a single table, though they did not do so. And the scenes suggest, by showing Lee’s sword on the table, that he surrendered it.

The only evidence that any printmaker completely understood the chronology of events that unfolded at and near Appomattox Court House on April 9 and 10, 1865, comes in a rare lithograph by one-time Currier & Ives artist Louis Maurer. It shows Grant and Lee meeting outdoors on horseback, but declares in its caption that the encounter occurred the day after surrender. Maruer modeled the print on a beautiful watercolor by Otto Boetticher, a Prussian-born Union soldier and military artist. Maurer’s adaptation remains one of the least-known but best-realized Appomattox prints. It portrays the two great adversaries planning for peace as grandly as they had waged a war.

Other painters attempted depictions of the surrender itself, with decidedly mixed results. Alonzo Chappel’s Surrender of General Lee was engraved for a book by Johnson & Fry of New York in 1865, but it misrepresents the McLean parlor as little more than a barracks. A much later Chappel painting became the model for The Surrender of General Lee, adapted for W.K. Steele of New York and featuring an accurate depiction of the room’s furnishings. The print proved popular enough to inspire a copy, but such a poor one that A. Lauder’s print of Peace seems more a parody than a piracy.

About the same time, a Mrs. M.F. Cocheu produced a design that pictures the opening and closing events of the war as Alpha (the attack on Fort Sumter) and Omega (Lee’s surrender). But in her ludicrous vision of the surrender, Lee, wearing a plumed hat, stands beneath an apple tree next to a rail fence, in full view of a wooden cabin; Grant appears to be smoking a cigar.

It is no wonder that some printmakers eschewed interpretive choices altogether. W. Webber’s Appomattox print for J.H. Bufford, for example, celebrated the village of Appomattox Court House, not the event, while another printmaker made the centerpiece of his design a map of the area, adding no portraiture at all.

Of course, there were printmakers who succeeded in dealing seriously and inventively with the surrender and its immediate impact on Southern troops. Both Burk & McFettridge of Philadelphia and Charles H. Walker of Washington, D.C., issued prints immortalizing the simple farewell address Lee gave to his troops the day after his meeting with Grant in the McLean House. The Burk & McFettridge print, issued in 1883, features a wreathed portrait of Lee, flanked by a symbolic handshake sealing the reunification. Walker’s more ambitious lithograph, issued 10 years later, included portraits of Lee in uniform astride his famous horse, Traveller, and in civilian clothes, along with a beautifully realized central scene of Lee surrounded by his loyal troops, as he returns tearfully to camp after the surrender.

Perhaps no print attempted more ambitiously to portray the surrender in its proper location, and with as many of its central characters as possible, than Major & Knapp’s 1867 lithograph of The Room in the McLean House, at Appomattox C.H., in which GEN. LEE Surrendered to GEN. GRANT. Commissioned as a fundraising device by Wilmer McLean, the print contains portraits of the personalities meticulously copied from period photographs. The portrayal of Lee and two aides is modeled after a photograph for which the general had reluctantly posed on the back porch of his Richmond house a week after the surrender.

The Major & Knapp original slightly exaggerates the size of McLean’s parlor, probably to accommodate figures of generals such as George Armstrong Custer, Philip Sheridan and George Gordon Meade. Its most glaring error is its identification of the man writing out the surrender terms as General Wesley Merritt instead of Colonel Ely Parker. Overall, though, save for the symbolic inclusion of so many military personalities, the print is perhaps the finest of all interpretations of the solemn moments during which Lee and Grant waited while the instruments of surrender were finalized.

Having McLean directly involved (he copyrighted the lithograph) undoubtedly contributed to the print’s truthfulness. But the unfortunate man who had fled Manassas to avoid the dangers of war ironically found himself ruined by peace. Union officers had all but plundered his parlor after Grant and Lee left. Tables and chairs were carried off and pictures removed from the walls, with small sums of money thrown at their owner by the souvenir hunters.

McLean hoped to regain some of his losses through sales of the Major & Knapp print. But despite the picture’s high quality, it apparently failed to earn McLean the fortune he had anticipated. Within a few years he abandoned his Appomattox home, and by the end of the century it had crumbled into ruins. It would not be reconstructed until after World War II.

The surrender did Wilmer McLean little good, but it did wonders for Robert E. Lee. Nothing Lee did in the field would inspire as many prints as his surrender. Remarkably, the same was true of Ulysses S. Grant. But it was Lee who may have gained the most from the prints’ proliferation after the war. Appomattox prints helped elevate his image and make it palatable to both the South and the North. The mere fact that he had given up the rebellion at Appomattox helped to cleanse Lee in the North, where all print production would originate, encouraging his depiction with all the dignity eyewitnesses ascribed to him.

Thus, even though Appomattox prints were really Grant prints intended for jubilant Northerners, Lee’s inclusion in the scenes put him on equal footing with the victor, perhaps because there could be little glory for Grant unless it could be shown that he had defeated a worthy foe. But this is not to underestimate the Appomattox prints’ impact on Grant, for he was their true hero, Lee only their implied one. And Appomattox prints may well have helped Grant win election to the presidency in 1868. They did, however, help Lee become an American again, and in time an American hero.

Intentionally or not, these popular graphics for the family parlor also helped elevate Lee to a status shared by no other figure of the Confederacy: a living symbol of reconciliation. By depicting him unbowed before Grant, printmakers demonstrated that reunion could be accomplished without subjugation. Appomattox prints showed Lee in surrender but not in humiliation, and thus made Lee an icon of peace, not defeat.

As one of his field commanders would ask in a Lee eulogy delivered five years later, What man could have laid down his sword at the feet of a victorious general with greater dignity than he did at Appomattox? Even Northern historian Charles Francis Adams Jr. would term the surrender the most creditable episode in American history — an episode without blemish — imposing, dignified, simple, heroic. So it would always seem in Appomattox prints, even the most fanciful among them.

Appomattox prints took a potentially humiliating event in Robert E. Lee’s life and transformed it into something of a triumph. Perhaps Grant himself sensed this, for the man the prints were supposed to celebrate disapproved of the entire genre. When a committee of Congress approached him soon after the war to propose a painting of the surrender for the Capitol Rotunda, Grant refused. He said he would never play a role in producing a picture commemorating a victory in which his own countrymen had been vanquished.

In a way, Appomattox scenes pleased neither the conquered nor the conquering heroes. But they certainly pleased the people.

This article was written by Harold Holzer, Gabor S.Boritt and Mark E. Neely Jr. and originally published in the Janurary 2006 issue of Civil War Times Magazine.

For more great articles, be sure to subscribe to Civil War Times magazine today!