Ittsei Nakagawa, a survivor of the Hiroshima bombing, once recalled Frank Oppenheimer asking, “Do you know the story of Genie in the Bottle? Well, the Genie’s out of the bottle. There is no way that you can get that guy in a bottle.”

As director Erik Nelson’s latest documentary, aptly named “Apocalypse ’45,” unfolds to scenes of destruction, it becomes abundantly clear to the audience that even prior to the atomic bomb droppings, the genie had been let out some time ago.

Nelson (“A Gray State,” “Grizzly Man”) was the first to bring the concept of colorized and remastered archival footage to audiences with his June 2018 release of “The Cold Blue,” a film dedicated to the heroic actions of the “Mighty Eighth” Air Force over occupied Europe. Like Peter Jackson’s 2018 release of the World War I documentary, They Shall Not Grow Old, Nelson has proven to have a knack for turning the 20th century’s greatest conflicts into a relatable and heart-rendering experience.

“I was very conscious of creating a time machine in the film to remove as many barriers between the experience of the war in the 1940s and the present-day viewer,” Nelson said in an interview with HistoryNet.

“The way to do that is to have only the voices of the people who were there, who lived it, and only the footage that was shot at the time. Nothing else. No narrator, no graphics. Nothing that would interfere with a hardwired connection into the experience.”

The 1 hour, 44-minute documentary is just that—an unsanitized, unvarnished experience of the harrowing final year of the war in the Pacific. Pulling from thousands of archival reels that were shot in color, Nelson and his team ultimately culled that number down to 140 before laboriously restoring them to digital 4K resolution.

Calling it “haiku history,” the documentary’s script is paired down—intentionally. “What’s the absolute bare minimum you can possibly say to not break the spell?” Nelson posited.

Told through the voices of 24 veterans, including Medal of Honor recipient Hershel “Woody” Williams, “Apocalypse ’45” brings into focus the horrors of war and serves as a tribute to those living and those who paid the ultimate sacrifice.

The opening minutes of the film lay bare devastating visuals of a bombed-out Japan before giving way to scenes of jubilation among American troops, home after a brutal four years of fighting.

The documentary then makes its way chronologically—from Pearl Harbor to the bloody shores of Tarawa, prior to focusing in the “the last, most brutal year of this war as it actually was, in the raw words and rawer images from the time,” Nelson stated in a press release.

Across the volcanic sands of Iwo Jima, viewers see fragments of the 36-day slog that killed 6,821 Marines and wounded another 19,217.

“We were thinking about saving our asses. That’s true. Because boy, it scared us. It scared us tremendously,” Al Nelson, an Iwo Jima veteran, can be heard saying as Marines on screen trudge through the otherworldly landscape.

Of the 21,000 Japanese soldiers committed to defending the island, only 212 defenders—1 percent of the original garrison—were still alive to surrender on March 26, 1945.

In the final land battle of the Pacific, the somber reels of Okinawa are punctuated by the reflective, tearful voice of Pharmacists First Mate Maurice Hubert, who made an astonishing five different landings in the Pacific campaign, including Iwo Jima and Okinawa.

“Got so that I didn’t know what my real name was. Everyone was ‘Doc, hey, Doc,’” Hubert says in the film, fighting back tears. “A lot of kids, a lot of casualties. I never like to remember any of those things. I always try to put it behind me. But I managed to survive. The good Lord was on my shoulder.”

It was to Nelson that Hubert revealed for the first time that Ernie Pyle, the famed war correspondent, had died in his arms.

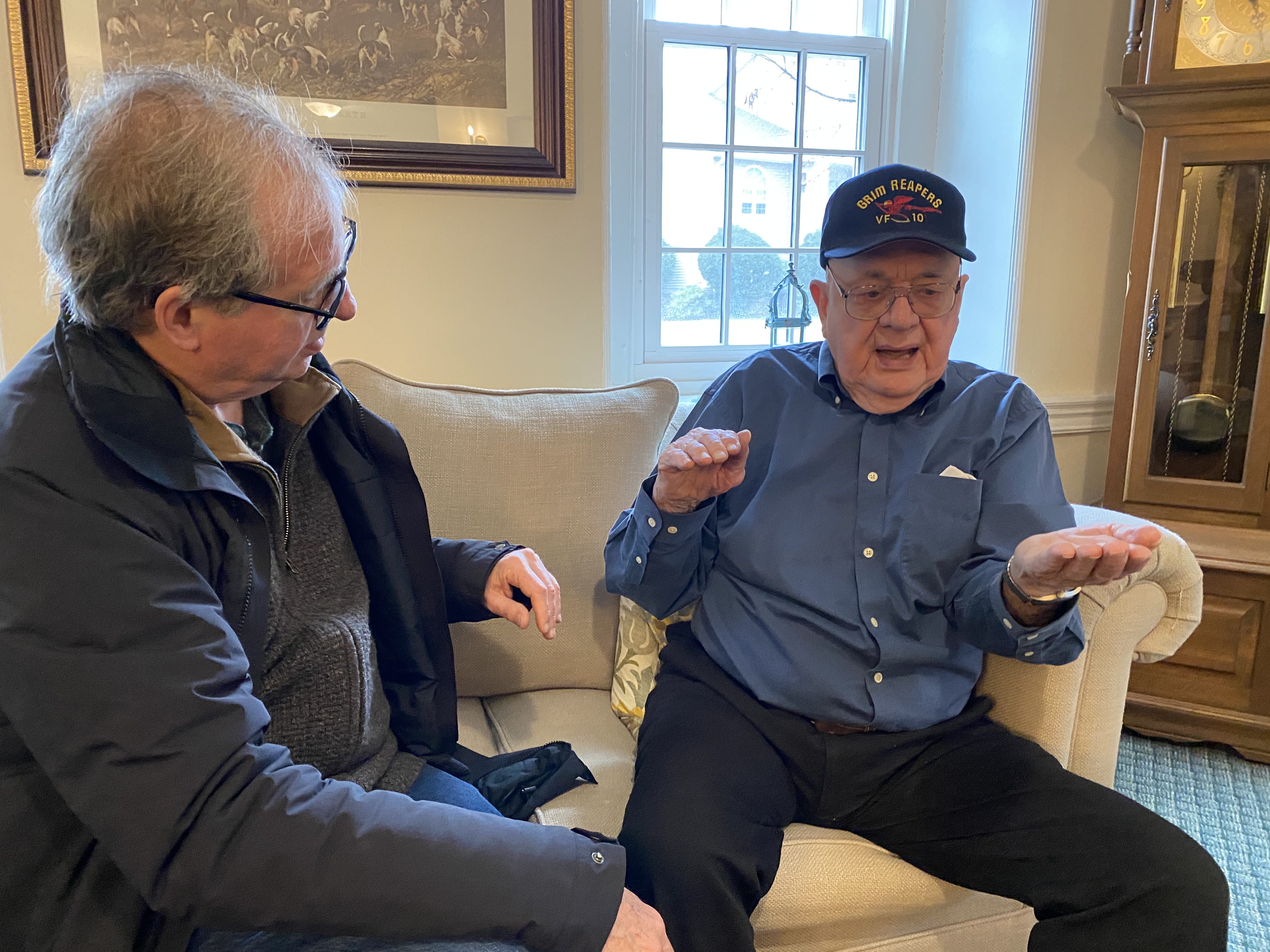

“He didn’t know until later,” Nelson said. “When he told the story I thought, ‘Wow, this is amazing,’ and then, ‘Damn, there’s no possible way I can use this in the film.’ … But I’m very conscious of the fact that I shook hands with the man who cradled the dying Ernie Pyle in his arms.

“Ernie Pyle’s enduring contribution … was [that he] translated the experiences he lived through … to indelible, classic reporting. By interviewing Maurice Hubert, I felt like the torch was passed from Ernie Pyle directly to myself.”

In many ways, Nelson, too, is trying to carry and pass the torch of the history belonging to a generation whose numbers diminish by the day. The 75th anniversary of the war’s end is just another weighty reminder for Nelson of the importance of the task at hand.

“As the last men who fought in that war—the men who literally saved the world—leave us, I felt it was vital that their voices be heard one last time,” he said.

Nelson’s attention to detail in sharing those voices—with the help of historians Ian Toll and Seth Peridon, whom Nelson says “knows World War II Pacific footage backwards and forwards”—is on full display in “Apocalypse ’45.”

“I was very conscious of this sort of responsibility to get it right to not do a disservice to them,” the director told HistoryNet. “Someone said to me, ‘Who’s going to notice?’ I said, ‘I’m going to notice. And trust me, vets are going to notice.’”

As a result, “Apocalypse ‘45” is as meticulous as it is powerful in the retelling of one of the bloodiest periods in world history.

“I hope that the quality of the filmmaking does their stories justice,” Nelson said.