Aides have been undermining their presidential bosses since the beginning

DEJA VU

As the summer silly season was ending, The New York Times published an op-ed portentously signed Anonymous.

President Donald Trump was “facing a test to his presidency unlike any faced by a modern American leader,” Mr./Ms. Anonymous declared. “Many of the senior officials in his own administration are working diligently from within to frustrate parts of his agenda and his worst inclinations. [Dramatic paragraph break.] I would know. I am one of them.”

For a week the article was the talk of the thumb-sucking class. In shielding the author’s identity, had the Times embraced best journalistic practices? (The paper acknowledged that doing so was a “rare step.”) Should a worried insider making incendiary charges not instead quit, and put his or her reputation behind those charges? (Advocacy dies in darkness.) Most tantalizing, who was Anonymous? Long odds were on Vice President Mike Pence, since Anonymous deployed the term lodestar—a guiding light, usually Polaris, the North Star—which Pence uncorks from time to time. However, most pundits looked for someone on the inner circle’s outer rim: a third-level person in a cabinet department, or a National Security Council aide.

Anonymous clearly got one thing wrong. Other American presidents have faced senior insiders working diligently to frustrate their bosses’ agendas and inclinations. Sometimes that resistance has resided at the hub of the inner circle—cabinet secretaries.

James Madison, Thomas Jefferson’s partner and protégé, was elected president in 1808, fourth to win the office, with a smashing two-thirds of the electoral vote. Everybody in the first Republican party having pulled together to put Madison over the top, everybody wanted a reward. Senator Samuel Smith of Maryland, a Capitol Hill powerhouse, wanted his younger brother Robert promoted from secretary of the Navy, his job in the Jefferson administration, to secretary of state. Madison wanted State to go to Albert Gallatin, the most talented man in the party after himself and Jefferson. In the end, the president bowed to political reality and tapped the junior Smith.

Smith assumed a key position at a fraught time. The world’s two fighting superpowers, Britain and Napoleonic France, each were seizing neutral American ships bound for the foe’s ports—and on the high seas, Britain was stopping American ships to seize alleged deserters. In addressing these issues, Smith had to deal with a mixed lot of British diplomats. One minister to the United States, David Erskine, was friendly but ineffectual, dangling promises of improved relations he could not deliver. Erskine’s replacement late in the summer of 1809, Francis James Jackson, was an anti-American snob. He derided the U.S. government as “a mob” with “mob leaders”; his wife slagged first lady Dolley Madison as “a pretty fat woman of the bourgeois class.”

Smith had the president’s help—maybe too much of it. Madison, for eight years Thomas Jefferson’s secretary of state, had definite ideas about how to handle the world scene. Smith had ideas too, which unfortunately differed from his boss’s. Local ties and imprudence were part of the mix. Smith passed inside diplomatic info to Madison’s congressional critics, who mainly hailed from port cities, like the Smiths’ own Baltimore, resentful of his administration’s inability to protect their shipping. Among Madison’s efforts to help merchants he grabbed at a French offer to call off its navy. Smith doubted France’s good will—and rightly; the ploy was insincere—but was cheeky enough to bad-mouth the French overture to the No. 2 diplomat in the British embassy, who reported to London that the Yanks were riven by infighting. In March 1811, Madison finally had a sit-down with his SecState. He told Smith he had been not only disloyal but incompetent. Smith wrote diplomatic letters “so crude and inadequate” that Madison had to “write them anew myself;” repeatedly, State Department business had been “thrown…into my hands.”

As a sop, the moon not being available, Madison offered to make Smith minister to Russia. How about Britain, Smith dickered, or the Supreme Court? Madison stood firm. Refusing the proffered Russian holiday, Smith quit and published an attack on his ex-boss. Glad to see Smith go, Madison installed fellow Virginian James Monroe at State.

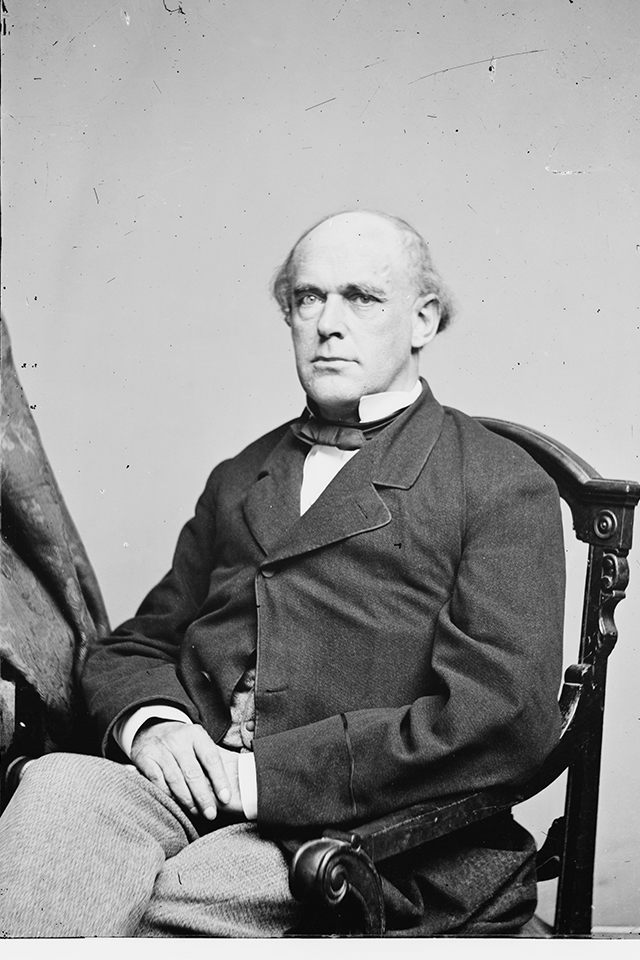

Madison and Smith had been scrapping on the eve of the War of 1812. Abraham Lincoln was fighting the Civil War when his cabinet began pestering him. Unlike Madison, Lincoln was the first president from a brand-new party—Republicans 2.0, a mash-up of antislavery Whigs, Democrats, and Know-Nothings. To unite this disparate band behind him, Lincoln filled his cabinet with men who had challenged him for the 1860 Republican nomination: William Seward at State; Salmon P. Chase at Treasury; Simon

Cameron at War; and Edward Bates as attorney general.

Seward and Bates were loyal and devoted. Cameron was loyal, but incompetent and crooked—less than a year later Lincoln canned him, offering to send him to Russia; unlike Smith, Cameron went. Lincoln’s most problematic secretary was Chase, an Ohioan who was smart, capable, and out for himself. Chase, like Smith, disagreed with his president about policy. In the 1840s Chase had belonged to the radical Liberty and Free-Soil parties—an antislavery résumé that made him a natural to ally with Radical Republicans unhappy at Lincoln’s cautious approach to emancipation. However, Chase’s main beef with Lincoln was that he wanted Lincoln’s job. Seward, Bates, and Cameron, all in their 60s, had let their White House dreams go. Chase, 53 when Lincoln took office, still yearned. He also had a campaign manager at home: beautiful daughter Kate. “Wherever she appeared,” an observer wrote, “people dropped back in order to watch her.” Chase needed a charm boost; he was proud, shy, and terrible at telling jokes.

Chase first moved against Seward. After the December 1862 Union Army debacle at Fredericksburg, Chase and his Radical allies accused Seward of running the administration—and running it aground. Seward offered to resign. Lincoln had a better idea. He invited the unhappy Radicals to meet with him and his cabinet, minus Seward. Each secretary testified that all had the president’s ear, and that Seward was not calling the tune. When Chase’s turn came, he agreed rather than buck the room. His timidity disgusted the Radicals. Why had he said one thing privately, and another when on the spot? Vermont Senator Jacob Collamer had a two-word explanation: “He lied.”

In 1864, with the war stalled and Radical Republicans still grumbling, Chase struck at Lincoln. In his 10,000 Treasury employees and 2,500 war bond salesmen, Chase had a ready-made political machine. That February Senator Charles Pomeroy (R-Kansas) wrote a letter, approved by Chase, that was sent to hundreds of Republicans touting Chase as “a statesman of rare ability.” The Pomeroy Circular, naively marked “Private,” immediately made the papers. Its only effect was to cause a surge of support for the president, even in Ohio. Chagrined, the malcontent offered more than once to quit. Lincoln kept him on until midsummer, when Chase proposed to resign once too often—and Lincoln accepted. He ensured Chase’s support through the election by dangling an offer to make him chief justice, replacing the late Roger Taney, a prize the president did not confer formally until December.

Cabinet secretaries are often big men in their own right, and the presidency is the biggest prize in politics. The real mystery is why more principled, ambitious men don’t make resistance their lodestar.