In the late 1920s, the sturdy Ford Tri-Motor helped convince a wary American public that commercial air travel could be safe, reliable and economical.

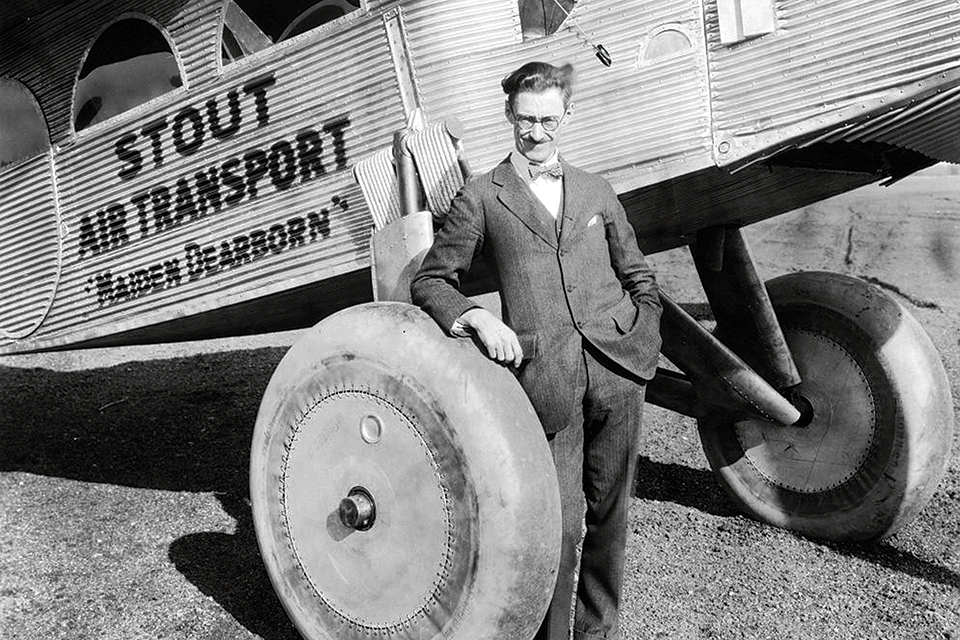

“I should like a thousand dollars, and I can only promise you one thing: You’ll never see the money again!” The request, penned by Bill Stout, a Dearborn-based engineer with a flair for promotion, landed on the desks of more than 100 influential Detroit businessmen in mid-1922. Stout was looking for enough money to finish an experimental airplane. He didn’t have a particularly clear idea of what he was going to do after that.

William Bushnell Stout was born in Quincy, Ill., in 1880. After graduating from high school in St. Paul, Minn., he briefly attended first Hamline University and then the University of Minnesota. Stout didn’t graduate from either university, but he did take some engineering courses at Minnesota.

After a stint at the Schurmeier Motor Car Company, which went bankrupt in 1912, Stout took a job as the auto and aviation editor for the Chicago Tribune. That same year he started Aerial Age, the first aviation monthly in the United States. The newspaper business proved ill-suited to Stout’s mercurial personality, and by 1914 he was again working for an undersized auto manufacturer, the Scripps-Booth Automobile Company. In 1916 he was employed by the Packard Motor Car Company as a sales manager before somehow becoming the chief engineer of its aviation division.

While at Packard, Stout oversaw the construction of several experimental planes under Navy contract toward the end of World War I. In 1919 he started his own engineering company in Detroit, and the following year he completed the Stout Batwing Limousine, an unusual-looking airplane with an enormous cantilevered wing (the plane was a shade under 23 feet long, with a 360-square-foot wing). It was built primarily of wood and was powered by a single Packard engine mounted in the nose.

Stout may have had a shaky grasp of aerodynamic principles, but he had a pretty clear sense of where the industry was headed. He saw a largely untapped market for safe and reliable air transportation—for both people and freight. He also realized that the multiple-engine approach used by Junkers and Fokker in Europe reduced the dangers posed by mechanical failure, while the all-metal construction pioneered by Junkers greatly increased overall reliability and made larger planes possible.

Stout sold the Navy on the idea of an all-metal, twin-engine aircraft and signed a contract to build six torpedo bombers. With those orders in hand, he moved into a large building at the corner of Piquette Avenue and Beaubien Street in Detroit, just across from Henry Ford’s original Model T plant. Stout’s ST-1 bomber looked modern enough, but it wasn’t particularly stable. At a ceremony in 1922 commemorating delivery of the first plane under contract, test pilot Eddie Stinson stalled it and crashed. Stinson survived, but the contract didn’t. The Navy terminated its deal with Stout, who had spent $162,000 developing the ST-1. He later described the disastrous ceremony as the “bluest day” of his life.

Recommended for you

Stout’s Navy bomber failure left him with little interest in selling planes to the government, and the feeling was probably mutual. His interest turned toward general aviation and the emerging market for air transportation.

Still convinced that the future of aviation was metal planes with multiple engines, Stout boldly made his request for a thousand dollars apiece from wealthy Detroiters, pitching them on the opportunity to help him make Detroit the aviation industry’s hub. Henry Ford and his son Edsel were among the investors he snagged with his pitch, and Edsel was so impressed with the idea that he helped Stout lobby other Detroit businessmen. Stout’s rather unusual fundraising campaign brought in about $30,000, with which he started up the Stout Metal Airplane Company in Dearborn, Mich.

The Fords took a keen interest in the progress of Stout’s prototype. Aviation was not an entirely new field for them. Despite the elder Ford’s pacifist leanings, the Ford Motor Company had manufactured Liberty engines for license-built de Havilland DH-4s during WWI. In 1909, at age 15, Edsel and a friend, Charles van Auken, had constructed a plane and made a few test flights—none of them more than six feet off the ground. Van Auken eventually crashed it into a tree at Detroit’s old Fort Wayne, emerging largely unscathed.

For some time after WWI, Henry Ford apparently still saw airplanes as war machines and had little interest in them. What caught his attention was Bill Stout’s talk of their value in transportation.

The first plane Stout built after his fundraising campaign, the 1-AS Air Sedan, resembled the Batwing Limousine, although it was constructed of metal. Encouraged by the results, he embarked on a second round of fundraising with the Fords’ help, raising about $100,000 in additional capital. He used that money to construct a new airplane designated the 2-AT (Air Transport—a name that underscored the machine’s practical nature). Nicknamed the Air Pullman, the 2-AT was powered by a single 150-hp Hispano-Suiza engine and featured a more conventional wing design than the 1-AS.

Stout’s Pullman was woefully underpowered, and during test flights near Mount Clemens, Mich., in late 1924, he told Henry Ford that he needed more horsepower, and in order to get that he needed more money. Ford looked at the plane and then turned his gaze back to Stout and said, “You don’t need more money, son. What you need is more plane.”

Within a few months the Ford Motor Company had bought out Stout’s other investors, and Henry Ford was in the airplane business. Ford went on to build airfields in Dearborn and Lansing, Ill., near the company’s Chicago South Side plant.

As Stout recalled years later, he and Ford had a conversation in early April 1925 about running a scheduled air service between the two Ford airfields. “This is Saturday,” Ford reportedly told him. “Can we start Monday?”

Stout hemmed and hawed and Ford turned and started to walk away. “We can start next Monday,” Stout called after him.

Thus, on April 13, about 1,300 pounds of Model T parts were loaded into a 2-AT in Dearborn and flown to Lansing, initiating America’s first scheduled air freight service. A few months later, Ford added a route from Dearborn to Cleveland, and in October Ford was one of the first private firms contracted to carry airmail for the Postal Service.

Meanwhile Stout was pushing forward on a larger airplane, the 3-AT, the first all-metal trimotor built in America. The ungainly aircraft made a compelling case for the old saw that “if it looks right, it’ll fly right.” The 3-AT failed on both counts. For starters, its fuselage was reminiscent of a dirigible’s gondola. As with his ill-fated Navy torpedo bomber, Stout had mounted the outboard engines almost flush with the wing’s leading edge, while the nose-mounted engine sat well below the fuselage centerline.

Test pilots were able to get the 3-AT into the air in November 1925, but that was about it. Ford’s chief pilot Rudolph “Shorty” Schroeder delivered his unofficial opinion of the plane not long after landing: “Forget it.” Ford agreed, calling the 3-AT a monstrosity and halting all further work on it.

A couple months later, in January 1926, a fire mysteriously broke out in Stout’s factory at Ford Field, burning it to the ground and destroying the 3-AT along with a few 2-ATs that were being assembled there.

After the 3-AT fiasco, Ford sent Stout out on the lecture circuit and brought engineer William Mayo in to straighten things out. Mayo had already demonstrated his ability to navigate challenging situations. Ford had placed him in charge of planning and supervising construction of the massive River Rouge Complex in Dearborn, the world’s largest integrated factory. Mayo brought Harold Hicks on to serve as chief engineer of Ford’s aviation division.

With an expanded budget and an assignment to come up with a clean-sheet design for a multiengine transport aircraft, Hicks and fellow engineer Tom Towle hired three more engineers fresh out of MIT and got to work. Henry Ford’s overall directive hadn’t changed. He still wanted an all-metal airplane with three engines and a minimum payload of about a ton. As one might expect of a man who was still building Model Ts, his requirements were all about durability and practicality, and he apparently had no particular interest in how fast the plane could fly.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our Historynet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Wednesday.

Ford was still operating its fledgling airline and had also bankrolled Richard Byrd’s controversial May 1926 flight over the North Pole in a Fokker F.VIIa/3m. Christened Josephine Ford after Edsel’s daughter, the plane ended up in a Ford hangar after the flight. A few months later, Harold Hicks’ team of engineers rolled out an all-metal aircraft that bore more than a passing resemblance to the Fokker.

Ford’s engineers had clearly benchmarked the F.VII, which was the absolute last word in commercial aviation at the time. The new transport, the 4-AT, would need to meet or exceed the Fokker’s performance, otherwise there was no point in putting it into production.

The resemblance between the two planes was purely superficial. The F.VII had a tubular metal frame covered in canvas and plywood, standard aircraft construction materials at the time. Going with all-metal construction meant the skin of the wings and fuselage could support much of the load the plane was subjected to during flight, eliminating the need for an extensive frame. However, the only metal strong enough and light enough for use in aviation at the time was corrugated aluminum.

Although the Ford Tri-Motor, as the 4-AT became known, looked like the Fokker F.VII, its construction more closely resembled that of the Junkers F13. In fact, when Henry Ford tried to sell the Tri-Motor in Europe, Hugo Junkers was able to block him by successfully arguing that its design infringed on patents his company held related to the construction of all-metal aircraft.

While Hicks and his team were designing the 4-AT, William Mayo escorted Bill Stout around the country on his lecture tour. When Ford put Mayo in charge of his aircraft project, one of his primary responsibilities was keeping Stout away from the engineers. Mayo got along well with Stout, and apparently never let on that their string of speaking engagements was intended, in part, to keep Stout from trying to design another aircraft.

Like Ford’s Model T, the Tri-Motor wasn’t noteworthy because it represented a major advancement in aviation technology. Rather, as Ford saw it, the 4-AT would be cheap, durable and reliable, and—as with his Model T—he was willing to sacrifice performance and appearance in order to meet those targets.

Unlike the planes of Fokker and Junkers, the Tri-Motor was designed from the outset for mass production. Shortly after the first 4-AT had been put through its paces, Ford started a production line at a factory near Ford Field. The marketing resources of Ford Motor Company were put to work promoting the plane, and Ford even established a pilot training school at the company’s airport.

The Tri-Motor hit the market in 1926 with an initial price of $42,000, far lower than that of the Fokker F.VII, and along with that low price came the backing of the world’s largest auto manufacturer. The airplane was about to transition from dangerous curiosity to a mainstay of American life.

Up to a dozen passengers aboard Ford’s Tri-Motor had reading lights and curtained windows in a cabin designed by John Kolle, an interior decorator at Hudson’s department store in downtown Detroit. They were also subjected to the deafening roar of three 300-hp Wright Whirlwind radial engines. Sound deadening would have been a challenge even if engineers weren’t concerned about the weight it would add. As it was, conversation was all but impossible and passengers were given cotton to stuff in their ears during the flight.

To simplify inspection and maintenance, the control cables were strung from the cockpit back along the outside of the fuselage. During flight the cables would vibrate against the airplane, further increasing cabin noise and rattling passengers’ teeth. Early models weren’t equipped with heaters, which added an extra bit of unpleasantness to the noise and vibration.

Still, the planes were—as Ford had intended—incredibly reliable, and the first airlines in the U.S. had little difficulty selling tickets on the “Tin Goose.” Customers took confidence from the plane’s multiple engines, all-metal construction and the safety of a pilot and copilot with redundant controls, not to mention the well-known Ford brand name.

As with the Model T, Henry Ford realized that making aviation a part of everyday life would require more than just cheap, dependable planes. Cars needed good roads, and airplanes needed good airports. Toward that end, Ford Field became a model airport where several innovations were tried out.

The airport had two runways, each over half a mile long, with most of that paved in concrete—the first time that material was used in runway construction in the U.S. In a rather odd admixture of modern and Victorian concepts, the airport terminal included a waiting room fitted out with rocking chairs and a fireplace. There was also a weather station at the field—a novelty that rapidly became standard. Ford built a hotel across the street from the terminal, with shuttle service provided into Detroit for passengers staying elsewhere.

Air traffic control got its start at Ford Field. Tri-Motors were equipped with radios, and pilots kept in touch with ground controllers during takeoff and landing. Cockpit radios also made it possible for Ford pilots to take the first steps toward instrument flight rules.

In addition to a powerful rotating spotlight, the field had a pair of directional broadcast antennas. The antennas were perpendicular to each other, with one continuously broadcasting a Morse code A (dot/dash) and the other broadcasting a Morse code N (dash/dot), both at the same strength and on the same frequency. By tuning the cockpit radio to the designated frequency and navigating so that the separate dot/dash and dash/dot signals blurred into a steady tone, pilots could be assured they were on a direct heading toward the airport.

this article first appeared in AVIATION HISTORY magazine

Facebook @AviationHistory | Twitter @AviationHistMag

Ford built 199 Tri-Motors between 1926 and 1933, in the process introducing the improved 5-AT, with 420-hp Pratt & Whitney Wasp engines. The company’s accounting during that era was notoriously bad, and thus it is difficult to determine whether its venture into aircraft production and airline operation was ultimately profitable. But if Ford managed to turn a profit from these businesses, it must have been a small one.

If anything, the Tri-Motors were too reliable. Fokker’s plywood airplanes were grounded after a thousand hours in the air, while the 4-AT came with a 3,000-hour service life. Years later Harold Hicks told an interviewer that Ford engineers had just guessed at that figure: “We hoped that they would last 3,000 hours.”

Most of them lasted a lot longer than that. In 1986, 60 years after the first 4-AT was built, Island Airlines retired the last Tri-Motor from scheduled passenger service in the U.S. Today the Experimental Aircraft Association still offers sightseeing trips in its own 4-AT and a 5-AT owned by Ohio’s Liberty Aviation Museum.

Ford Motor certainly had the resources to stay in aviation, but when push came to shove Henry Ford was not a risk-taker. According to Hicks, Edsel was always the driving force behind the company’s involvement in the aircraft business.

Advancements in aviation design soon rendered the Tri-Motor obsolete. If the 5-AT looks decidedly modern when compared with the open-cockpit de Havillands that represented the pinnacle of American aviation in the early 1920s, it looks like an antique next to the Boeing 247, launched in 1933, when the last Tri-Motor was built.

After the success of the Tri-Motor, Ford made a push into personal aircraft. The company’s first effort, the single-engine Flivver, was a diminutive single-seater that Henry Ford touted as a plane for everyman, although its suggested list price of $28,000 made that claim rather hard to believe. Less rugged than the Tin Goose, the Flivver weighed only 350 pounds empty. A succession of prototypes were built, with the final one crashing in the Atlantic in February 1928, killing Ford test pilot Harry Brooks.

Henry had become good friends with Brooks and took his death rather hard. He apparently had no intention of quitting the airplane business, but the pilot’s death seems to have made him so risk-averse that the aviation division could not keep up with the times. Edsel’s and Mayo’s interest in keeping the division relevant in a rapidly changing industry often conflicted with the elder Ford’s conservative attitude and increasingly arbitrary judgment. Though Edsel was nominally the president of Ford Motor, his decisions were subject to review and revision by his father.

Not long after Brooks died, the Depression hit and Tri-Motor sales dried up. At the time Ford’s aviation division employed more than 1,600 people, with 45 engineers on staff. Most of the division was laid off in the summer of 1932, and the last 5-AT rolled out of the factory on June 7, 1933.

Ford’s foray into aviation lasted just under a decade, and although the Tri-Motor didn’t do much for the company’s bottom line, its low cost, durability and safety helped introduce Americans to passenger air travel. “My greatest contribution,” Bill Stout would say, right up to the end of his life, “was getting Henry Ford interested in building planes.”

Richard Jensen is a writer and historical preservation consultant based in Sioux Falls, S.D. Additional reading: The Fabulous Ford Tri-Motors, by Henry M. Holden; The Saga of the Tin Goose, by David A. Weiss; and The Ford Tri-Motor 1926-1992, by William T. Larkins.

This feature originally appeared in the November 2020 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here!