A single investor’s ruin sent the infant United States economy into a terrible tizzy

LATE IN THE AFTERNOON on Friday, September 12, 2008, at the offices of the Federal Reserve Bank on Liberty Street in New York’s Financial District, a panel of government officials informed Lehman Brothers CEO Richard S. Fuld Jr. that his bank was on its own. The Federal Reserve and the Treasury Department would no longer be propping up failing investment banks like his. Lehman had just reported a multibillion-dollar loss and faced billions in additional losses from heavy investments in mortgages to people with

limited ability to pay on houses now worth less than the amounts of those mortgages. If Lehman Brothers could not find a buyer by Sunday night, the company would be bankrupt on Monday morning.

Banks like Lehman Brothers had financed the housing boom of the early 2000s by assembling thousands of individual mortgages from all over the country into “structured investment vehicles”—investments sold to individuals and institutions. When those “vehicles” worked properly, borrowers’ payments funded dividends, enriching investors. However, to attract buyers for their mortgage securities, Lehman and other investment banks generally had to guarantee regular dividends. As more and more borrowers defaulted on mortgages, banks had to make up a growing gap between payments received and the dividends that were guaranteed, creating a problem that metastasized into a crisis.

Worse, products originally marketed as insurance for default risks on these loans were unregulated, unmonitored, and had themselves become incredibly risky. Banks were heavily invested in one another’s offerings and in one another’s default insurance. Ratings services ostensibly in the business of objectively assessing these investments for their degree of risk routinely rubber-stamped the issuing banks’ own assessments of risk. And banks were terrible at evaluating investment risk.

When Lehman Brothers was unable to close a deal with Barclays by the end of the weekend, the company was finished. Word leaked out on Sunday night that Lehman was going to file for bankruptcy, and as soon as the bank’s doors opened on Monday morning, Lehman Brothers folded.

The closing put 35,000 employees, including Fuld, out of work, a toll that paled beside the failure’s effect on the financial sector, which was immediate and staggering. Every bank to which Lehman owed money faced significant losses. AIG, which insured trillions in mortgages, suddenly needed $70 billion dollars to stay afloat.

As the crisis rippled through the American economy everyday people found it difficult or impossible to borrow money. Lending for homes, cars, and small businesses shrank to the point of invisibility. Retirement savings evaporated. Property owners with interest-only loans lost their houses when they could not refinance their mortgages. Real estate values plunged. Homeowners who at least could struggle through and make payments were doing so on houses worth far less than the amount they had borrowed, in neighborhoods suddenly full of foreclosed houses. At one point during this period, American households had lost $6 trillion in home equity.

The events of 2008 have many precedents—not for nothing do some analysts joke about America’s “shampoo economy—boom, bust, repeat.” However, the 2008 breakdown, sparked by a single investment bank’s failure, has striking parallels to America’s first great national financial crisis, the Panic of 1796-97.

The American economy of autumn 2008 featured a nationwide tangle of barely comprehensible investments not easily unraveled and an immeasurable level of risk. The spring of 1796 model boasted a knot of personal loans tying together merchants up and down the Atlantic coast. Akin to their modern counterparts and their structured investment vehicles, parties in the Panic of 1796-97 carried multiple mortgages and loans on millions of poorly surveyed acres, some of which borrowers did not even own. As in 2008, in 1796 merchants suddenly had no way to evaluate whether a borrower was risky or safe or whether collateral stood behind a loan. And that first spasm struck when the United States was new and small, and the country’s fate could be, and nearly was, undone by one man’s personal fiscal failure.

That man was Robert Morris, famous as a Founding Father and for singlehandedly financing the Revolution. Born in 1734 in Liverpool, England, Morris emigrated to Maryland where his father traded in tobacco. By age 24, the younger Morris was a partner in a Philadelphia shipping concern. He prospered sufficiently to enter Pennsylvania politics, serving in the first and second Continental Congresses. Initially skeptical of the Declaration of Independence, he eventually signed that document. When war began, Morris put his resources at the rebel government’s disposal, loaning money to buy ammunition, clothing, and food for troops, paying Continental soldiers’ salaries, and seeing to it that his employees spied on the insurrectionists’ behalf.

Robert Morris was foremost a trader. Not formally educated, he carried himself with a no-nonsense, all-business demeanor. He had an eye for deals and a reputation for pragmatism. His firm dealt in real estate, imports, and, briefly, slaves—although he later became a solid abolitionist. Morris married rather late, at 35. His wife Mary White was from a well-connected Virginia family. She and Robert had five sons and two daughters. The family filled a house at the corner of Sixth and High Street in Philadelphia. By 1775, when the Revolution erupted, Robert was considered America’s wealthiest man, a label sufficient to guarantee almost unlimited credit that he put to profitable use.

Morris did profit from the war. He owned a fleet of privateers, armed civilian vessels commissioned by the government to seize British merchant ships. Those prizes were auctioned, along with their cargoes, at warehouses he owned, enriching Morris and raising eyebrows high enough to cause Congress to investigate him in 1779. The inquiry cleared him, and he was named the new nation’s first superintendent of finance, the equivalent of today’s Treasury secretary.

In 1785, Morris, now out of government, arranged to become the exclusive supplier of tobacco to the Farmers-General, a monopoly authorized by France to sell American tobacco in that country. Soon after, the United States named as minister to France Thomas Jefferson, a Virginia tobacco planter. Jefferson arrived in Paris intent on persuading France to rescind Morris’s exclusive deal with the Farmers-General and achieved that goal. Jefferson’s coup hurt the quality of Morris’s sotweed, as tobacco was also known, and, coupled with a troublesome intermediary in London, caused him severe losses. To cover his losses, the financier, who had come to eschew smaller deals in favor of opportunities national in scope, looked to a single enormous venture in land speculation.

In 1790, a real estate syndicate that had gone deep into debt buying a tract in western New York of roughly six million acres defaulted

on that purchase. Early in 1791, Morris arranged to assume title to the vast holding. In those days, no national bank issued standard paper currency, nor was much gold and silver circulating. In that vacuum, entrepreneurs like Morris issued personal notes—essentially IOUs, often unsecured. Personal notes promised to pay a certain sum on a certain date in gold and silver or bank notes—notes issued by individual banks redeemable at that institution for gold or silver. Notes were usually transferrable. The holder of a note promising to pay, say, $500 could use that note to purchase $500 in goods from a party willing to accept that note at face value. An individual with good credit could roll over notes—the day a note was due, a debtor could sell a new note for gold and silver or bank notes, using the proceeds to pay off the preceding note. Banks were willing to redeem some notes, making them akin to checks. A merchant holding a $10,000 note might use that note as collateral to issue notes of lesser value, promising creditors that he would pay them when people paid him the money he was owed. One personal note could back another, creating a web of indebtedness that assumed every party to be an honest participant who would, upon demand, redeem his note.

Using personal notes, Morris bought millions of acres and began to sell off parcels. One buyer, James Greenleaf, helped Morris sell more than a million acres to the Holland Land Company. More than 30 years Morris’s junior, Greenleaf was as flashy as Morris was stolid. At 23, Greenleaf had married a Dutch baroness. By 28, he was a millionaire and by his own account able to secure investments from Amsterdam’s leading bankers. While he and Morris were speculating in western New York, Greenleaf was also working on a deal to buy 3,000 lots in the new national capital, Washington, District of Columbia. The District’s board of commissioners was authorized by the federal government to sell the lots to encourage development, which was not taking place at a breakneck pace. Greenleaf invited Morris to join him in that venture.

Morris had cleared a tidy profit from his New York land sales, but he was still deeply in debt, and the 1793 failure of a London investment bank had left him short on access to capital. The sums involved are telling. Morris paid $333,333 for the New York land, using borrowed money, when only about $27.3 million in currency was circulating in the United States; today, this would be comparable to borrowing $162 billion using no more security than a promise to make good—and that doesn’t represent the full extent of Morris’s borrowings.

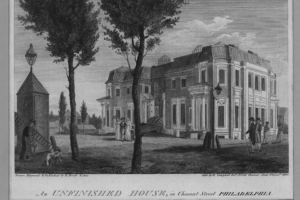

On Christmas Eve 1793, Morris and Greenleaf, joined by John Nicholson, assumed ownership of 6,000 empty lots in DC—a deal of the size Morris sought, but one with big trouble written all over it. The partners were agreeing to pay more than $68,000 annually for those thousands of lots, priced for resale at $300 apiece, but which nobody wanted to buy in a city that existed mainly on paper. The terms of the purchase required they build brick houses on 140 of the lots they bought. In addition to making loan payments, they were also obligated to loan the District almost $32,000 per year. Greenleaf swore he could tap into streams of Dutch money to cover their nut. Morris could not resist.

“I can never do things in the small,” he told a friend. “I must be either a man or a mouse.”

The venture’s DC holdings sat unsold. France invaded the Dutch Republic, shutting off Greenleaf’s supposed faucet of cash. Taking stock of their Washington debacle in late 1794, Morris, Greenleaf, and Nicholson concluded that the only remedy was more speculation. In spring 1795, they chartered the North American Land Company, a strange hybrid of stock company and real estate investment syndicate. The enterprise held—or claimed to hold—title to or options on six million acres. In fact, the North American Land Company was a forerunner of the Ponzi scheme, using later investors’ money to pay off early investors. Nicholson, Greenleaf, and Morris desperately needed funds to cover their obligations in Washington, DC. The three promised investors they could take dividends in land. This arrangement appealed to Morris and partners, who had little money but—they thought—plenty of land. However, the partners’ land was generally worthless and poorly surveyed, and the North American Land Company did not own all the land its principals imagined.

Desperate to get their paws on bank notes and hard currency, Nicholson, Morris and Greenleaf were mortgaging anything in sight. In July 1795, Nicholson and Morris discovered that Greenleaf, using Morris’s lines of credit, had been borrowing money for his own uses. Plus, instead of forwarding revenue to the District to cover the syndicate’s obligations, he had stolen that money. To get rid of their slippery partner, Morris and Nicholson immediately sought to buy out Greenleaf, but had no cash. They got rid of Greenleaf by giving him notes backed by those lots in Washington. Through 1795 and 1796 Morris and Nicholson flogged the North American Land Company’s offerings, trying to interest investors in vast tracts of vaguely specified yet glowingly described property in and around the Appalachians.

By the end of 1796, Morris was broke. His notes were floating all over the country. He could not roll them over; creditors would no longer lend him money. When they came due, he had to default, with immediate local and national impact. Recalling that winter, Benjamin Rush, a Philadelphia doctor, tallied 150 business failures in six weeks, with bailiffs arresting and imprisoning almost 70 citizens for debt in two weeks’ time near year’s end.

Philadelphia’s population was about 35,000. Today, in a city of Philadelphia’s modern size, those figures would equate to about 6,900 business failures and 3,200 people imprisoned.

Morris spent 1797 capitalizing on a legal dodge—“keeping close,” they called it. Failure to repay was not a crime, so the law limited the

where and the when of arresting debtors. For example, bailiffs could not arrest debtors in their homes unless the individuals had invited the bailiff in. Debtors were supposed to be allowed to travel freely on Sundays, but this could be dangerous, as they might be kidnapped, held overnight, and then duly arrested on Monday.

Once arrested, debtors would be confined to a prison operated by the state or city; generally, there was no provision for them to be released unless all of their creditors agreed. In that respect, going to debtor’s prison could be far worse than being convicted of a crime, which carried a sentence of fixed length. A creditor could keep a debtor in prison until he died there if he was unable to discharge his debts, although this was not a frequent occurrence.

In February 1798, however, Philadelphia authorities clapped Morris into a cell in the debtor’s prison on Prune Street, six blocks from a house the financier owned in which President John Adams was living. Morris was not alone in stir. Supreme Court Justice James Wilson tried to flee creditors only to be imprisoned for his debts in New Jersey, then Delaware, and finally North Carolina, where he died of malaria.

Morris’s failure hit investors and merchants hardest. In an era of few banks, with those in business far-flung, private individuals extended much of the nation’s credit. Many borrowers counting on Morris to repay notes so they could pay back their loans were forced into bankruptcy. Those bankruptcies rippled further, overtaking individuals who had lent this circle of investors money. As the ripples spread, even creditworthy would-be borrowers found the vault locked. Merchants trading in imports and exports relied heavily on credit to cover obligations while merchandise was on the water or stored awaiting sale or delivery. During the panic these merchants found access to credit cut off. Some were ruined; others slashed their operations. Debtors unable to avoid prison stayed inside indefinitely. Some, like Morris’s partner Nicholson, died behind bars. Others persuaded creditors they had no means to repay, so why keep them locked up? A fortunate few had debts repaid by friends and family.

Several states had bankruptcy laws by the time Robert Morris landed on Prune Street, where one of his callers was a fellow Founding Father. Pressure for a national bankruptcy law grew when Americans learned that former President George Washington had gone to a prison to visit the man who financed the Revolution. In similar manner, the panic demonstrated the harm to all when merchants could not clear bad debt in an orderly fashion—jailings for debt brought business dealings almost to a standstill, another shock to the economy. Congress passed a national bankruptcy law in 1800. Under it, Morris gained release from debtor’s prison in 1801. He retired to the family home on Philadelphia’s outskirts, where he died in 1806.

The Panic of 1796 reverberated for decades. When Morris went bankrupt, the Washington DC properties at the root of his woes reverted to the federal government. However, these lots were encumbered with mortgages and liens dating to Morris’s and his partners’ desperate scramble to generate cash. Sorting them out took years.

The panic’s effect on individual lives lasted generations. Almost wiped out, Revolutionary War hero “Light-Horse” Harry Lee, could not send his younger sons to his oldest boy’s alma mater, William and Mary University. Sydney went into the navy in 1820. Robert E. enrolled at the U.S. Military Academy in West Point in 1825. George Meade fared a little better than the elder Lee. A Philadelphia merchant, Meade was one of many whose assets vanished in the panic, while his debts remained. Under the new bankruptcy act those debts were discharged. Meade’s son sought to reestablish the family business overseas, but failed, consigning George’s grandson and namesake to West Point. The younger George Meade and Robert E. Lee crossed paths at Gettysburg in 1863, almost seventy years after the panic.

The North American Land Company, the mutant enterprise that Morris, Nicholson, and Greenleaf formed to bail themselves out, survived longer. Morris’s heirs were still fighting over the fate of the company’s few remaining assets well into the 1870s.

The panic and the disruptions in trade caused by Napoleon’s wars in Europe depressed the American economy until the early 1800s. Recovery rode in on several factors. The first was the reduction of credit risk. Merchants surviving the financial cataclysm more or less intact could be assumed to be stable and therefore good risks. And the economy generally expanded as the United States negotiated an end to British and French interference in trade and, as the Napoleonic Wars continued in Europe, remained neutral. Lessened risk and greater peace had the economy booming as the country sold goods to all sides in the European conflict.

As with the 2008 crisis, the Panic of 1796-97 arose when loss of confidence in a few principal players triggered a cascade of defaults. Since Morris and Nicholson no longer could borrow, default was the only outcome. Their collapses plunged individuals expecting repayment into chaos, just as the Lehman Brothers bankruptcy threatened institutions and individuals invested heavily in Lehman financial products.

Fortunately, economics is less of a mystery today than in the 1790s. In 2008, quick action by the Federal Reserve and the Treasury Department contained institutional failure and ensured a relatively orderly unwinding of billions in bad mortgages. Economists may not have learned enough to prevent bubbles and busts, but at the very least they have learned how to mitigate the damage they cause. Even so, the immensity of the crisis in 2008 meant years of stagnation and hobbled growth. But that’s the problem with economic crises—with the exception of the Great Depression, they end not with a bang, but a wheeze.