Both Summoned to Glory and Abe are worthy recent additions to a catalog of more than 10,000 books that have sought to unravel the mysteries of Abraham Lincoln.

By Richard Striner

Rowman & Littlefield, 2020, 533 pages, $35

Richard Striner’s Summoned to Glory is the work of a writer who has authored two previous books on America’s 16th president, race, and slavery and obviously admires his subject. For Striner, Lincoln is a man who “will stand for all time as an exemplar of human life fulfilled….[a man who] redeemed the American promise, made it real as no other man has.”

The author tackles Lincoln’s life chronologically, devoting most of his attention to the president’s public life while quickly dispatching topics that have sometimes preoccupied other biographers. He concurs with those who believe Lincoln loved Ann Rutledge and was devastated by her death, and acknowledges the speculation surrounding Lincoln’s sexuality while dismissing the likelihood that he was homosexual.

When considering Lincoln’s marriage and domestic life, Striner has no definitive answer as to the nature of his relationship with Mary Todd other than its many challenging features. His insight that history might never have heard of Abraham Lincoln had he married Ann Rutledge instead suggests the important role that Mary played in her husband’s success and the significance of shared ambition to their marriage.

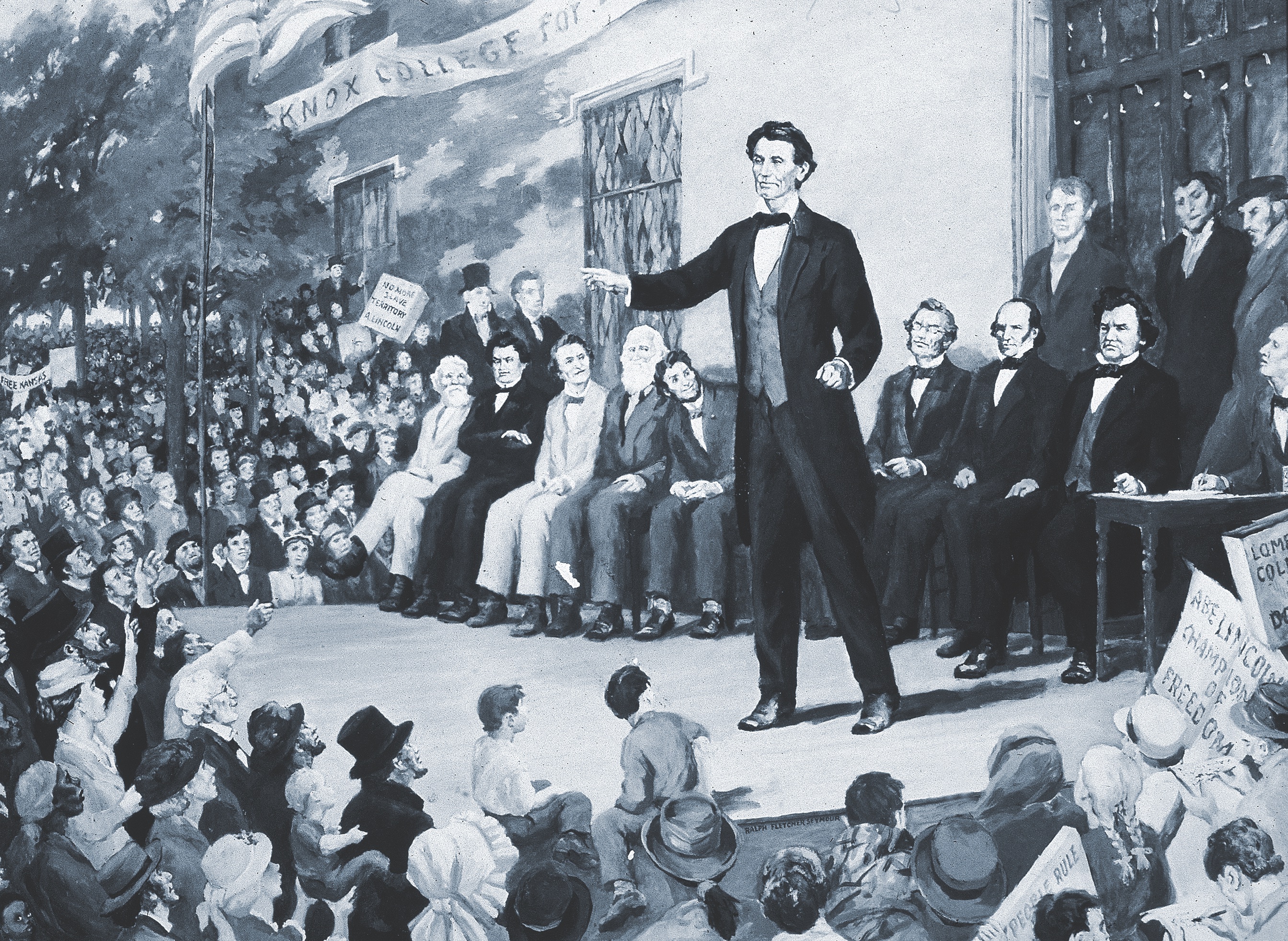

Lincoln found “his life’s work,” Striner contends, during the Kansas-Nebraska crisis of the 1850s, and he places at the core of his book Lincoln’s attitudes toward race and slavery. According to Striner, those attitudes were not clearly formed until Lincoln was in his 40s, and there is no reason to assume he automatically adopted those of many of his neighbors.

The Declaration of Independence’s signers, Lincoln argued, “did not intend to declare all men equal in all respects…[but rather] to “declare the right to equality so that the enforcement of it might follow as fast as circumstances should permit.” Equality was a standard that “even though never perfectly attained, [was] constantly approximated.” On the eve of the Civil War, Lincoln would say, “All I ask for the Negro is that if you do not like him, let him alone.”

Lincoln, Striner argues, was a “holistic thinker” possessing great strategic abilities hidden behind humor and self-deprecation. “The reputation of ‘Honest Abe,’” he writes, “would blind so many to the depth of his shrewdness and cunning.” His analysis that Lincoln’s intent was from the beginning “to put slavery on a path to ultimate extinction” concurs with the recent interpretation by James Oakes and others.

Lincoln would save the Union his way, and by 1863 he had made ending slavery the central Federal war aim. His Unionism, Striner insists, “must be seen in the context of what the Union would stand for….Final victory depended on the presence of a mind…that could visualize power and direct it. Lincoln possessed that sort of a mind.” His assassination at the hands of John Wilkes Booth, the author concludes, stole “an extraordinary future…from America.

in His Times

By David S. Reynolds

Penguin Press, 2020,

1,088 pages, $45

Abe, on the other hand, embraces a different approach to its subject. Magisterial in scope (and length), it is the work of an accomplished cultural biographer and historian of the 19th century. While his book proceeds chronologically, David Reynolds lards each chapter with frequent references to Lincoln’s contemporaries; the literature, music, theater, and popular culture of the day; and the manner in which these people and external factors shaped Lincoln both personally and politically.

To Reynolds, Lincoln was a man in, but not necessarily of, his time. He was by nature “a fatalist, but not a pessimistic one,” someone prepared to take “a middling course.” The author likens him to Charles Blondin, a famed tightrope walker of the era. “He could take his place securely in the center because he had a genuine understanding of antislavery and proslavery extremists that led him to see that radical militancy could…destroy the Union.”

In analyzing Lincoln’s antislavery views and activities, Reynolds emphasizes the ways in which he cloaked his hatred of slavery with public moderation. He consistently eschewed the harsh rhetoric of the abolitionists, avoiding the demonization of slaveholders and positioning the issue as a conflict “between statute…and natural law.”

To be successful politically, Lincoln could not be as progressive in public as he was in private, and by the late 1850s, Reynolds maintains, he was adept at “using a conservative cover to appeal to moderates while delivering a fundamentally radical message.” In the words of a contemporary, “Lincoln was a radical—fanatically so—& yet he never went beyond the People. Kept his views & thoughts to himself…he never told all he felt.”

Likewise, Lincoln “was secretive about his own religion, but innovative and insistent on the uses of religion in American public life.” He believed in a powerful, unknowable God, moral standards, and the Bible. Reynolds concurs with Striner in acknowledging Mary Todd Lincoln’s central role in her husband’s political success and credits her as a smart and nuanced woman who was nonetheless a difficult marriage partner: “Her behavior, varied at best and chaotic at worst, provided him with home practice in the kinds of issues that he confronted publicly.”

Reynolds ultimately acknowledges Lincoln’s caution, shrewdness, honesty, humility, and winning humor as the ingredients necessary to his success and his continued hold on the American public’s imagination. “His principled vision and his disarming modesty,” he writes, “remain an inspiration to everyday Americans and political leaders alike.”

Summoned to Greatness is the more traditional biography of the two, offering a deep dive into the details of an essential American life. Abe is both something more and something less, as its readers may learn less about the political twistings and turnings or the personal dramas that colored Lincoln’s life. For those stories, there are Striner and many other first-class biographers. But readers will come away from Reynolds’ book with a deeper understanding of what made the nation’s 16th president (with apologies to the late James Flexner), “the indispensable man.” Perhaps reading both is to be recommended.