The former French emperor’s grandnephew campaigned for good government and civil rights in America

H.L. MENCKEN CALLED IT “the Bonaparte smile”—not a grin, but a display of disquieting confidence by fellow Baltimorean Charles Joseph Bonaparte, foe of cronyism and bias in government. “The Republicans hate him as fervently as do the Democrats, for his favors have been impartially distributed and his fatal smile has beamed upon all,” Mencken wrote. Bonaparte was a grandson of Jérôme Bonaparte, Napoleon’s younger brother. Grandmother Elizabeth Patterson Bonaparte, a Paterson, New Jersey, beauty, won Jérôme’s heart as the 19-year-old Frenchman was visiting Baltimore in 1803. The best-known Napoleon was a genius at reforming French law, making it more workable and intelligent. His great-nephew’s focus was curbing an American political spoils system that focused power and privilege in the plutarchy. Charles fought the power first in Baltimore and later as attorney general under President Theodore Roosevelt. He founded the nation’s first public detective bureau, later dubbed the Federal Bureau of Investigation. He championed the exercise of federal power, including the power to protect African-Americans’ civil rights, trampled underfoot following the 1896 Supreme Court decision on segregation, Plessy v. Ferguson.

Bonaparte could afford to fight. Grandmother Elizabeth, daughter of a wealthy Baltimore merchant, fell for Jérôme Bonaparte and vice versa. The couple wed in Baltimore on Christmas Eve against the French emperor’s wishes, later sailing to France to see him. After Napoleon barred the couple from landing, Jérôme’s commitment to Elizabeth dissolved. She delivered son Jérôme Jr. on July 5, 1805, in London, then returned to Baltimore. Unusual for the day, Elizabeth controlled her own money, circulated to and from Europe at least eight times, and ranked her own ambition with Napoleon’s and Alexander the Great’s. When Napoleon tried to strip her of the Bonaparte name, she replied, “Madame Bonaparte is ambitious and demands her rights as a member of the imperial family.” She tried and failed to raise Jérôme Jr. like a prince; he married a strong-willed New Englander, Susan May Williams. The second of their two sons was Charles Joseph.

A great reader and rider, Charles studied at Harvard, finishing his law degree at 24 in 1874. He worked in Baltimore. Land left him by his father allowed him the wealth and independence to marry Ellen Channing Day, daughter of a wealthy lawyer. Grandmother Elizabeth left him $750,000.

Bonaparte dealt in real estate and represented poor and African-American plaintiffs. He began his career as a reformer by exposing local election fraud. In 1881, he helped start the Civil Service Reform Association of Maryland, and, in 1885, the Baltimore Reform League. Fearing “kakistocracy”—government by the least qualified—he called crony politics “an asylum for political bums.” He saw the bar to reform as the fact that “so many persons who ought to and in 1885 be and often have been in prison are, not only out of prison, but actively, if not conspicuously, engaged in the government of the country.” The remedy: “To improve our courts and prisons, we must first of all change the men who establish and control them and purify the customs and traditions which put these men where they are; in short, to reform our administration of justice, we must first and thoroughly reform our politics.”

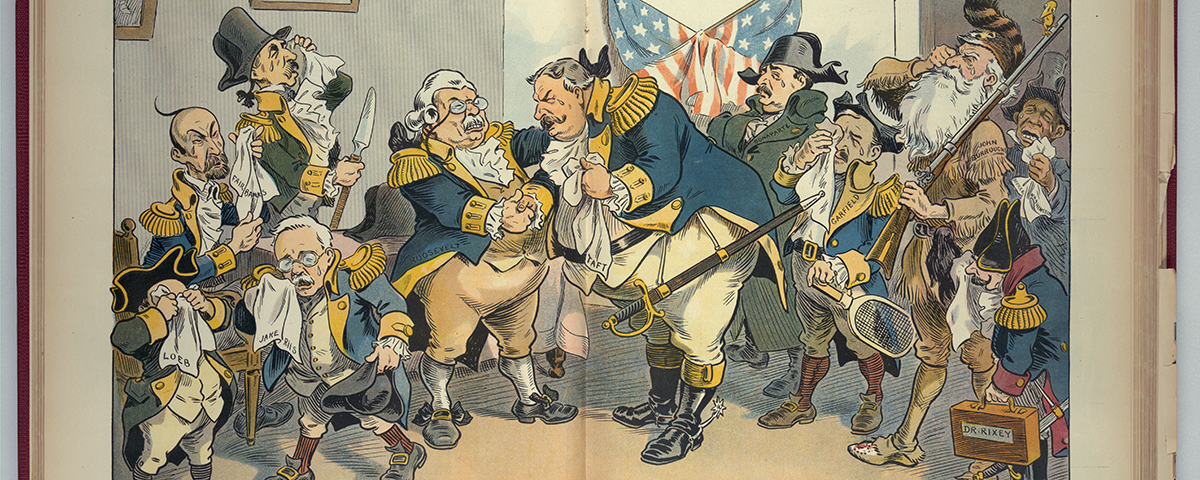

Quick-witted, Bonaparte was known as an orator. By 1895, his efforts had resulted in state laws on ballot integrity, civil service, and sleaze. “The battles of the latter-day Bonaparte have been against the windmills of corruption and breach of public trust,” Mencken wrote. “Were he president of the United States, the penitentiary walls would bulge.” He earned the nicknames “Charlie the Crook Chaser,” and “goo-goo,” a tag for advocates of good government.

Bonaparte sought no spotlight, but Roosevelt, an acquaintance since Harvard and kindred progressive, shoved him into the glare. As president, Roosevelt hired Bonaparte to root out fraud in the Indian Territory and the Post Office, in 1905 named him secretary of the navy, and moved him in 1906 to attorney general. Bonaparte began what became successful suits against American Tobacco, Standard Oil, and other corporations for monopoly activity. He likened trusts to swine. “They crowd their smaller and weaker fellows from the feeding trough so that these don’t get their fair share of our national prosperity,” he said. “The problem is how to so fence off the great beasts as to give the little ones a show….”

Paucity of resources—he had to borrow Secret Service agents for probes, a legal overreach—vexed him. In 1908, he and TR schemed a new agency. He hired 34 agents, declaring the Bureau of Investigations would pursue only interstate commerce and anti-trust cases. In 1935 it became the Federal Bureau of Investigation.

As U.S. attorney general, Bonaparte maintained his interest in civil rights, campaigning against disenfranchisement of black voters in Maryland, where blacks made up about 18 percent of the population. Maryland state constitutional amendments proposed in 1905 and 1908, which included conditions involving testing and duration of residency, would have kept many blacks from voting. However, thanks to Bonaparte’s vigorous opposition, the amendments failed.

Of 50 cases Charles Bonaparte argued before the U.S. Supreme Court, a lynching stands out. Authorities in Chattanooga, Tennessee, charged, convicted, and sentenced to death Ed Johnson, a poor black man, alleging he raped a white woman in 1906. Johnson’s defense argued that Tennessee had deprived the accused of a fair trial. Presenting a host of objections, black attorneys aiding the appeal at great personal risk got U.S. Supreme Court Justice John Marshall Harlan to stay Johnson’s execution. Chattanooga Sheriff and former Confederate Army officer Joseph Shipp, ignored the stay, sent away all but one of seven guards at his jail, and emptied all cells on Johnson’s floor but his. A mob stormed the jail and hanged Johnson from the bridge connecting the segregated city’s black and white sections. Rioters pumped 50 shots into the dying man’s body.

Two federal agents interviewed witnesses in Chattanooga and charged Shipp and several rioters with criminal contempt. Before the Supreme Court in Washington, DC, on March 2, 1909, Bonaparte, in a six-hour closing argument, detailed the weakness of evidence against Johnson and strong evidence implicating Shipp and others in Johnson’s murder.

“Only recently have lynchings become so numerous that the whole country was aroused to earnest discussion of mob violence and a remedy for it,” Bonaparte said. “It is indeed useless to seek relief unless the judiciary can punish those who snatch and kill the men it has imprisoned…. If the life of one whom the law has taken into its custom is at the mercy of a mob, the administration of justice becomes a mockery.”

In the only instance in which the U.S. Supreme Court has asserted jurisdiction in a criminal case, the court voted 5-3 to convict six defendants of criminal contempt, with Justice William Moody recusing himself. Shipp, sentenced to 90 days in jail, was feted with a parade and a monument in Chattanooga. The others also drew brief sentences. Still, the federal judiciary had taken a stand, puncturing the shield of states’ rights and upholding the rights and protections enumerated in the Bill of Rights and the 14th Amendment right to due process. The ruling, coupled with the 1909 arrival of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, began a decades-long fight against mob justice. Bonaparte’s marathon argument bespoke the tenacity Mencken was hailing when he wrote that taking on Bonaparte “would be like attempting to stop a dynamo with a walking stick.”

This story by senior editor Sarah Richardson appeared in the April 2019 issue of American History Magazine. For more stories, subscribe here.