An American History Online Exclusive

The Sage of Baltimore thought his countrymen’s beliefs were worthy of a less-evolved species, and told them so

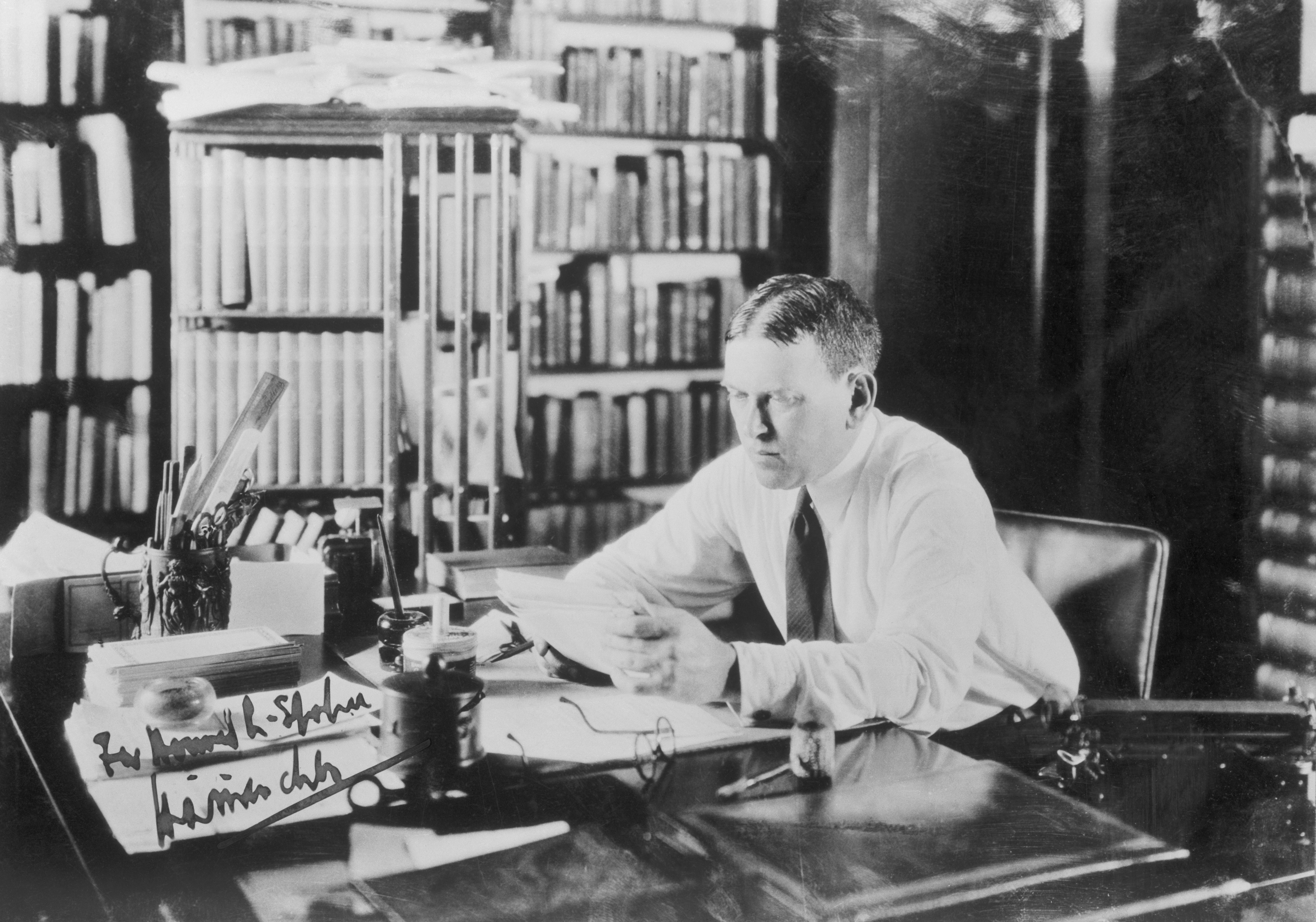

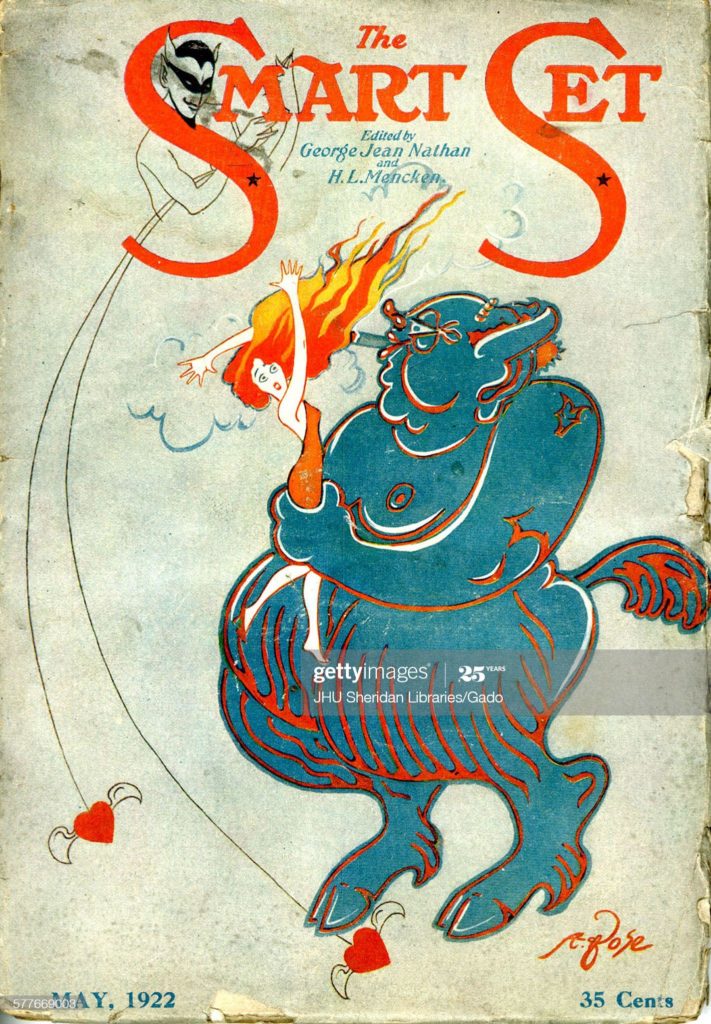

Exactly 100 years ago, in 1920, the most famous and controversial American journalist of his day published a book containing 869 examples of “wisdom” he claimed were the beliefs held by the average American. Henry Louis Mencken touted The American Credo as a portrait of the “National Mind.” Credo wasn’t flattering to fellow citizens, which surprised no one familiar with the author’s writing. H.L. Mencken had made his name satirizing “boobus Americanus” and trumpeting his belief that the average American was an “ignoramus and poltroon.”

Mencken redeemed his snide cynicism about his countrymen with his writing style, which was outrageous, exuberant, and hilarious. “We live in a land of abounding quackeries,” he explained, “and if we do not learn how to laugh, we succumb to the melancholy disease which afflicts the race of viewers-with-alarm.”

Mencken never succumbed to that syndrome. During a career spanning the first half of the 20th century, he wrote thousands of newspaper and magazine articles and more than a dozen books—every one suffused with his uniquely gleeful grouchiness.

In 1920, Mencken was 39, and feeling grouchier than usual. World War I had left him disillusioned. He opposed American entry into the European slaughterfest and he was angered by the federal government’s wartime censorship of the press and prosecution of anti-war dissidents. His spirits did not improve in 1919, when that same government, in a flourish of sanctimony, outlawed the balm that soothed his sorrows—booze. In this mood, he practically gagged when he read patriotic essays—or, as he called them, “rhetorical gas-bombs upon the subject of American ideals.” Americans don’t really believe in the lofty ideals of liberty and justice proclaimed in the Declaration of Independence and the Gettysburg Address, Mencken wrote. What the average American really believes is a mishmash of ancient superstitions, spurious pseudo-science, racist tripe, ethnic stereotypes, dunderheaded clichés, and crackpot theories. So he gleefully compiled a comic list of ludicrous notions Americans really believe.

He claimed his list to be “very serious”—the birth of “an entirely new science” he dubbed “descriptive sociological psychology.” Of course, he was kidding. The American Credo came straight out of his head—with some suggestions from cronies. But Mencken knew Americans, having worked for 20 years as a reporter covering cops, courts, and City Hall in his hometown, Baltimore, before moving on to the gaudier spectacles of national politics. His job was, he wrote, an education in “the worldly wisdom of a police lieutenant, a bartender, a shyster lawyer and a midwife.”

He laid out 488 examples of that worldly wisdom in the 1920 edition of American Credo, then added 381 more in a revised edition published in 1921. A century later, these “beliefs” seem amusingly ridiculous, yet disturbingly familiar.

180: That children were much better behaved 20 years ago than they are today.

774: That people who offer one a firm handclasp are very upright and honest.

414: That politics in America would be improved by turning all the public offices over to businessmen.

230: That many soldiers’ lives have been saved in battle by bullets lodging in Bibles which they carried in their breast pockets.

783: That the chief pastime of young medical students is hurling human arms and legs at each other in the dissecting room.

[hr]

In 1920, as in 2020, Americans harbored some odd ideas about health:

56: That whiskey is good for a snake-bite.

287: That fish is a brain food.

360: That oysters are a great aphrodisiac.

198: That if a cat gets into a room where a baby is sleeping, the cat will suck the baby’s breath and kill it.

489: That monkey-glands will restore a man of 85 to the vigor of 21, and cause him to elope with a Swedish servant girl and become the father of twins.

[hr]

The average American of 1920 held strange notions about sex:

144: That every country girl who falls has been seduced by a man from the city.

669: That many women who live in fashionable apartment houses have liaisons with the elevator boys.

671: That most women begin street flirtations by dropping their handkerchiefs.

77: That a Sunday School superintendent is always carrying on an intrigue with one of the girls in the choir.

653: That the first thing the Bolsheviks did in Russia was to nationalize all the women, and the all the most toothsome cuties were reserved for Trotsky and Lenin.

229: That chorus girls spend the time during the entr’actes sitting around naked in their dressing rooms telling naughty stories.

239: That all the girls in Mr. Ziegfeld’s “Follies” are extraordinarily seductive and that at least 40 head of bank cashiers are annually guilty of tapping the till in order to buy them diamonds and Russian sables.

[hr]

Mencken painted Americans as tormented by fears of being duped:

30: That ginger snaps are made of the sweepings off the floor in the bakery.

181: That the cashier of a restaurant, in adding up a customer’s check, always adds a dollar, which is subsequently split between himself and the waiter.

513: That jewelers, in cleaning or repairing costly baubles, invariably remove the original stones and insert others made of paste.

556: That the woman writer on an evening newspaper who gives advice to the lovelorn is invariably a man with a flowing beard.

514: That all moving pictures of English country life are staged in Fort Lee, New Jersey.

302: That whenever a will case gets into the courts, the lawyers gobble up all the money and the heirs come out penniless.

347: That the licorice candy sold in cheap candy stories is made of old rubber boots.

15: That something mysterious goes on in the back rooms of chop suey houses.

[hr]

Americans in 1920, like Americans in 2020, believed all kinds of nasty ethnic stereotypes:

63: That French women use great quantities of perfume in lieu of taking a bath.

101: That German babies are brought up on beer in place of milk.

466: That English women are very cold.

741: That a Jew always outwits a Christian in a business deal.

399: That all negroes who show any intelligence whatever are actually two-thirds white and the sons of United States senators.

313: That whenever there is a funeral in an Irish family, the mourners all get drunk and assault each other with clubs.

375: That when a Chinese laundryman hands one a slip for one’s laundry, the Chinese letters which he writes on the slip have nothing to do with the laundry but are in reality a derogatory description of the owner.

[hr]

Mencken claimed men and women have weird theories about women and men:

160: That there is something slightly peculiar about a man who wears spats.

787: That women with red hair or wide nostrils are possessed of especially passionate natures.

452: That no man who is not a sissy can ever learn to thread a needle or darn a sock.

114: That the editor of a woman’s magazine is always a lizzie.

479: That a man always dislikes his mother-in-law, and goes half-crazy every time she visits him.

283: That a woman can’t sharpen a lead pencil.

134: That if a dog is fond of a man, it is an infallible sign that the man is a good sort, and one to be trusted.

135: That blondes are flightier than brunettes.

256: That brunettes are more likely to grow stout in later years than blondes.

[hr]

The average American of 1920 daydreamed about the lives of plutocrats:

216: That all millionaires are born in small ramshackle houses situated near railroad tracks.

125: That millionaires always go to sleep at the opera.

267: That women who are in society never pay any attention to their children, and wish they would die.

247: That all the millionaires of Pittsburgh are very loud fellows, and raise merry hell with the chorus girls every time they go to New York.

547: That women who are able to afford servants wear kimonos during the greater part of the day and read best sellers.

262: That John D. Rockefeller would give his whole fortune for a digestion good enough to digest a cruller.

759: That in the old days whenever a millionaire gave a midnight supper party, a semi-clad chorus girl would dance on the table, and the guests would drink champagne out of her slipper.

[hr]

Mencken happily catalogued American superstitions:

48: That it is bad luck to kill a spider.

60: That if one’s nose tickles, it is a sign that one is going to meet a stranger or kiss a fool.

61: That if one’s right ear burns, it is a sign that someone is saying nice things about one.

62: That if one’s left ear burns, it is a sign that someone is saying mean things about one.

138: That if one touches a hop-toad, one will get warts.

615: That a piece of bread and butter, if dropped, will always fall butter side down.

376: That an old woman with rheumatism in her leg can infallibly predict when it is going to rain.

102: That a man with two shots of cocaine in him could lick Jack Dempsey.

[hr]

Mencken reported that the average American had odd notions about American history:

218: That George Washington never told a lie.

398: That George Washington died of a heavy cold brought on by swimming the Potomac in the heart of winter to visit a yellow girl on the Maryland shore.

422: That General Grant was always soused during a battle, and that on the few occasions when he was sober he got licked.

492: That Aaron Burr possessed an irresistible charm for all the women with whom he came in contact, and that the virtue of even the most strait-laced was a very poor risk if left in a room alone with him as long as ten minutes.

691: That Daniel Webster delivered his greatest orations when he was so drunk that he had to hold on to a table to stand up.

711: That Edgar Allan Poe wrote all his stuff while sobering up after sprees.

839: That the late J. Pierpont Morgan was the easiest mark the fake antique dealers of Europe had discovered in 250 years, and that a syndicate of Italians actually built five factories in Italy for the sole purpose of manufacturing fake Rembrandts to sell to him.

604: That both Abraham Lincoln and Jefferson Davis were the illegitimate sons of Henry Clay.

[hr]

Some wisdom Mencken recounted fit no known category except amusement:

116: That all senators from Texas wear sombreros, chew tobacco, expectorate profusely, and frequently employ the word “maverick.”

756: That at every girls’ boarding school there are several female rakes who do nothing but smoke cigarettes, tell risqué stories, and put the other girls hep to a lot of things they should not know.

855: That if all the money in the world were to be divided, within a year the same men would have it again.

679: That the Indians in wild west shows are in reality not Indians at all but painted Chinamen.

607: That when one asks a bell-boy in a hotel in Budapest to get one’s suit pressed, he reappears in a few minutes with a large blonde.

[hr]

A hundred years after Mencken published his list, it is impossible to determine which items Americans actually believed and which sprang from Mencken’s mischievous mind. It seems quite possible that he came up with a few of the more bizarre items while quaffing illegal tankards of his favorite beverage, beer, with convivial cronies. The lines about the Budapest bellboy and George Washington’s “yellow girl” practically reek of malt and hops. If Mencken, who died in 1956 in his beloved Baltimore, somehow were to revisit the land he loved to mock, what would he say that today’s average American believes? We’ll never know. But he might reuse at least one item from his 1920 list:

245: That there is something peculiar about a man who wears a red tie.