Alexander Simplot and his gang of young friends haunted the streets and steamboat landing of the frontier town of Dubuque, Iowa, in the 1840s. “We had no trains to meet or depots to visit and could only judge of the stir in the outer world by the coming of the stage coach and the passing steamers laden with their passengers and freight, and at that time the boats were numerous and heavy laden,” Simplot later wrote. “We seldom missed a boat during the early hours of the night….I know of nothing which struck my imagination more vividly than the appearance of one of our large steamers…approaching you at night with bows headed directly for you…with its two large open furnaces, one on each side, like huge fiery eyes, and the thick black smoke surging from the chimneys, with the bellowing cough of the escaping steam…aglow at the landing as some base monster darting out of the darkness.” Such scenes inspired the poetic nature of the boy who would become one of America’s most distinguished Civil War illustrators.

Simplot was born in a log cabin in Dubuque on January 5, 1837. Few other structures stood in the town, which was then only four years old. His father, a wealthy French merchant specializing in the buying and selling of grain, sat on the Board of Aldermen under the city’s first mayor. Although Alexander’s father died in 1846, the family, consisting of Alexander, his mother and five siblings, managed to maintain its status in Dubuque’s upper class. The Simplots were wealthy enough, Alexander later recalled, that, as a boy, he was the only child in town with a drum, which had been shipped up the Mississippi River from St. Louis.

During his childhood days in Dubuque, Alexander exhibited considerable talent as an artist and portrayer of landscape scenes, but his playmates looked down upon his endeavors, and his relatives sought to discourage him. His family did encourage his education, however, and he was sent to Rock River Seminary at Mount Morris, Ill., where he met John A. Rawlins, future U.S. Army assistant adjutant general and later secretary of war under Ulysses S. Grant. In 1856 Simplot entered Union College in New York and enrolled in the classical course. Two years later he received his degree, and his commencement speech, titled “Plea for Painters,” addressed the status and dilemmas of the creative person in society. Upon his return to Dubuque, Simplot took a position as a schoolteacher, suppressing for a while, at least, his artistic interests.

At the outbreak of the Civil War, Simplot joined 3,000 residents of Dubuque at the levee along the Mississippi River. They cheered the departure of the Jackson Guards and the Governor’s Greys as they boarded the steamer Alhambra and left for Davenport, the headquarters of the 1st Iowa Regiment. Simplot recalled that the city had never witnessed “kinder wishes or heartfelt adieus,” and that “eyes were dimmed with mistiness and hearts throbbed heavily with painful yet tender thoughts.” Despite the drizzling rain and muddy streets, there were women with parasols, men in top hats and children dressed in their Sunday best swarming over the landing, crowding on rooftops and hanging out of the windows of nearby buildings to catch a glimpse of the volunteers as they steamed off to war.

The 24-year-old Simplot recorded those events of April 22, 1861, by producing a pencil sketch that he sent to Harper’s Weekly, a national illustrated newspaper with a circulation of 115,000. On the strength of this work, the editors hired him as a special correspondent.

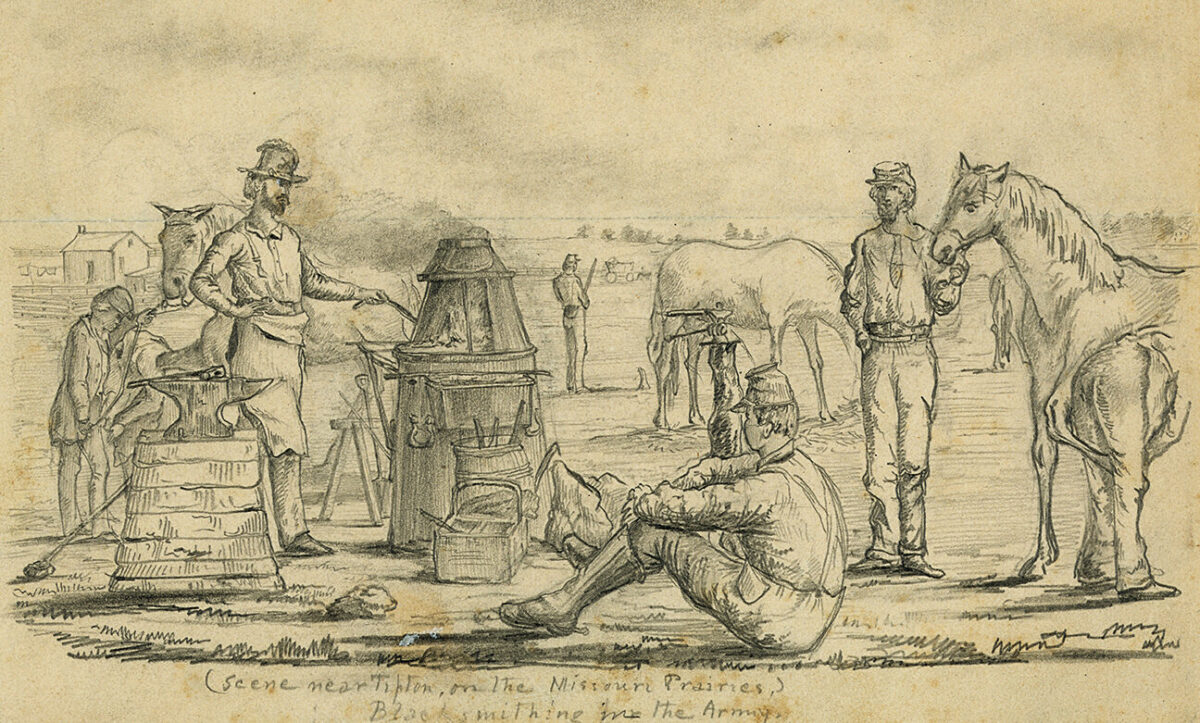

The repressed artist jumped at the opportunity to chronicle the drama of the clash between the North and the South. Harper’s commissioned him to set up headquarters at Cairo, Ill., where Simplot spent much of his time sketching fortifications, camps and soldiers at the juncture of the Mississippi and Ohio rivers. He relied on his extensive knowledge of the river and his expertise in drawing steamboats, both gained during his boyhood, to accurately portray the vessels that would soon be converted to troop transports and warships. Harper’s used his drawings to illustrate the buildup of Federal forces in the West in preparation for the invasion of the South.

Initially Simplot and the other correspondents had little action to report and began calling themselves the “Bohemian Brigade” because of their carefree existence. The adventuresome life appealed to Simplot. He was the only artist known to have sketched scenes and written of the daily activities of the Civil War correspondents. They would sit up late into the night, holding long philosophical discussions, drinking heavily and having a good time. Often the conversations ended in “some sort of pitched battle” in which the reporters “turned over chairs, capsized tables, spilled ink, and wrecked books.”

Simplot had been guaranteed safe conduct behind enemy lines, where his curiosity and social contacts led him (a pistol tucked in his pants as a precaution) to attend a dinner party at a home in Confederate southern Missouri. When his host discovered that his visitor was an artist for Harper’s, “He was especially desirous that I should represent (or draw) his home and have it published in Harper’s under the heading of ‘A Home of a Notorious Rebel,’” Simplot reported. He later recalled the event fondly and was convinced that he had eaten in the home of a Confederate and dined with Rebel officers dressed in civilian clothes. He wondered if these officers would clash with Northern armies at a later date.

In the winter of 1861-62, Simplot began to report on the forces under Brig. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant. The artist was delighted to be reunited with now Captain Rawlins, his former classmate at Rock River Seminary, who was on Grant’s staff as an assistant adjutant general. As a result of his relationship with Rawlins, Simplot enjoyed special privileges, including an appointment as assistant engineer in the War Department, which allowed him to closely observe and report on Grant and the actions of the general’s troops.

Simplot was present at Memphis on June 6, 1862, when a fleet of Union ironclads defeated eight lightly armed Confederate ships. The citizens of Memphis watched from the bluffs while their city’s defenses crumbled. Although Simplot did not have “the opportunity to witness the detail of the battle,” the young Iowan sketched the destruction of the Southern vessels. Since he was the sole artist with the Northern forces, his sketches were the only depictions of this crucial victory to see print. On June 28 and July 5, Harper’s published nine of Simplot’s illustrations, including “The Great Naval Battle Before Memphis.” Those drawings brought him his greatest fame and recognition.

A few months after Memphis, Simplot’s coverage of the Civil War came to an end. He had developed a chronic case of dysentery, and in early 1863 he left the Army and returned to Dubuque. During his two years as a correspondent, Harper’s had published 51 of Simplot’s sketches, ranking him 13th among the 28 special artists to whom 10 or more published drawings can be credited. According to his notebooks, Harper’s paid him from $10 to $25 for each published sketch—approximately $1,250 for two years’ work. Fortunately, Simplot was a man of independent means, and the relatively low pay did not much matter to him.

After a two-year sabbatical, Simplot sketched one more scene for Harper’s. He captured the grandeur of Ulysses S. Grant’s glorious return to his hometown of Galena, Ill., on August 18, 1865. In his portrayal, the artist included the triumphal arch that spanned Main Street and soared above the 25,000 well-wishers. Harper’s published Simplot’s sketch on September 9, 1865. His career with Harper’s had begun with Alhambra on Dubuque’s wharf and concluded with a salute to a widely acclaimed hero of the Civil War and future president of the United States. Simplot’s artistic life would never again reach such rarified heights.

In 1866 Simplot married Virginia Knapp, a former pupil who was 10 years younger. Simplot later boasted that Virginia, whom he called the “Belle of West Dubuque,” had once danced with General Grant. The Simplots raised nine children.

For a brief time, Simplot engaged in the dry goods business with two of his brothers, but retailing did not appeal to him and he soon returned to sketching and engraving views of Dubuque and the surrounding area. Later, he became active in the business of buying and shipping grain; speculation in that commodity, however, proved to be Simplot’s financial undoing. According to members of his family, he lost $100,000 of his inheritance on the wheat market. Virginia, distraught over the decline in the family’s financial fortunes, died in 1904 at age 57.

Although Simplot never regained his financial losses, he was still active as a community leader. Dubuquers always remembered him as an “aristocrat” and a fastidious dresser whose speech was “flavored with quotations from the Bible, Poor Richard’s Almanac, and the classics.” In his later years the artist relished his role in the Early Settlers Association, founded in 1865 and open to all males who were residents of Dubuque as of July 4, 1840. Simplot served as president and secretary of the organization for many years. More important, he played a prominent role in the Julien Dubuque Monument Association sponsored by the Early Settlers.

Julien Dubuque, the first white settler in Iowa, for whom the town was named, died in 1810. The Monument Association worked to create a structure in honor of the Frenchman. It wanted to construct a tower reminiscent of the “Castles of the Rhine,” and turned to Simplot for a sketch that might be used as a basis for the monument. Simplot’s work of art eventually led to a Galena limestone monument that measured 12 feet in diameter and 28 feet in height. Since the Meskwaki Indians, with whom Dubuque had lived for some time, had buried him on the bluffs overlooking the river, his body was exhumed and reburied in the stone-tower monument, which was dedicated on a festive Sunday afternoon in late October 1897.

Simplot lived out his remaining days in the household of his son Alwyn. He delighted in serving up batches of French toast and speaking his father’s native language. He often traveled to Minnesota to visit many old acquaintances who lived in St. Paul’s large French quarter, and he stayed in contact with his wartime friend, Whitelaw Reid of the New York Herald. Simplot was reticent to discuss his Civil War experiences with family. At the breakfast table, however, he often kidded his children that the juice from pink grapefruit was just like the “blood from the wounded soldiers.”

Alexander Simplot died on October 21, 1914, at the age of 77, and was buried in the Civil War section of Dubuque’s Linwood Cemetery. At his death, Simplot was the city’s oldest native-born son, a distinction he proudly acknowledged. Although he lived a full and long life, gaining fame as an illustrator during the Civil War, the artist always came back to his roots in his boyhood home. He claimed that the inspiration of his life remained the joy and prosperity of his childhood along the Mississippi.

Simplot’s original sketches are highly valued by historians and art collectors today. Although many of his drawings have been lost over time—one of Simplot’s sons recalled that as a boy he often used his father’s Civil War sketchbooks for drawing pads—those that have survived still constitute a valuable documentation of Civil War history.

Originally published in the June 2006 issue of American History. To subscribe, click here.