The Chaco War of 1932-35 was the biggest South American conflict in the 20th century, involving the continent’s only landlocked countries, Bolivia and Paraguay. While Bolivia pursued a World War I–style strategy, conducting controlled trench warfare with slow but secure movements, Paraguay adapted its limited military resources to the characteristics of its territory for a remarkable war of movement similar to Germany’s Blitzkrieg in World War II. Bolivia tied its larger air force to supporting its cautious advances, while Paraguayan General José Félix Estigarribia described his airplanes as “the eyes of the army,” but used them far more aggressively.

One anecdote from September 23, 1934, epitomizes the camaraderie between Estigarribia and his aviators. A Paraguayan Fiat CR.20bis flown by Captain Tomás A. Ruffinelli Jr. was being chased by a Bolivian Curtiss-Wright CW-14R Osprey crewed by Sub Lts. Alberto Paz Soldán and Sinecio Moreno. When Ruffinelli checked his tail, he heard firing and the sound of broken glass. Turning his gaze forward again, he saw his windscreen was riddled with bullet holes. That slight head turn had saved his life. Estigarribia met Ruffinelli a couple of days later and asked him for his age. When the pilot replied that he was 24, the general answered, “Wrong, just two days old!”

The disputed territory behind the war was the Chaco Boreal, a huge flatland roughly the size of Colorado. Although it is covered with quebracho trees, cacti, thorn scrub and tall grass savanna, the area is arid except during the November to April rainy season, which turns it into muddy swampland. At night temperatures fall drastically from highs above 100 degrees to well below freezing. As a result, every afternoon during the war the aircraft mechanics were forced to drain the coolant from the radiators to avoid their being broken by the frozen liquid, then refill them every morning. Omnipresent dust rendered engines unserviceable with alarming speed.

Its flora notwithstanding, the Chaco had the characteristics of a desert—a hellish green desert. Its lack of geographical landmarks made aerial navigation extremely difficult, and pilots often got lost over the vast expanse.

The Chaco had been historically claimed by Bolivia since the days of the Spanish empire, but it was better connected geographically and ethnically with Paraguay. When oil was discovered in the region near Villa Montes, both governments took steps to explore and occupy it. This led to the first clashes in 1928, culminating four years later in open conflict.

When the war effectively began in July 1932, Bolivia’s air assets were entirely based in Villa Montes, near the Chaco border. The Bolivian air corps at that point consisted of three Vickers Type 143 Bolivian Scouts, five Vickers Type 149 Vespa IIIs and three Breguet 19A.2 two-seater army cooperation aircraft. Collectively they formed the 1st Air Group under Major Jorge Jordán Mercado, with a fighter squadron and a reconnaissance-bomber squadron. The Paraguayans facing them had six Wibault 73C.1s in the 1st Fighter Squadron and five Potez 25A.2s in the 1st Reconnaissance and Bombing Squadron, but not all of those aircraft were operational.

Although slower and less maneuverable than their opponents, Paraguay’s Potez 25s survived 12 out of 14 dogfights with Bolivian planes and even shot one down. The secret to this, apart from the Potez’s robust design, lay in the defensive doctrine implemented by Major Vicente Almandos Almonacíd, an Argentine volunteer in the French air service during World War I who was a member of the Argentinian military mission in Paraguay in 1932. Almonacíd taught his pilots that when attacked by enemy fighters they should fly at treetop level and reduce their speed to near stall, zig-zagging every 10 seconds. With that defensive maneuver the faster enemy fighters would typically overtake the two-seater too rapidly to aim at it. The pilots were also instructed to fly in a tight V formation, so that the crews could cover each other’s rear and flanks. Consequently, a fighter attacking a formation of three or four Potez 25s from 6 o’clock would face return fire from six to eight machine guns. The results could be lethal.

The first large military operations began in Boquerón, an isolated Bolivian-occupied post in the south-central Chaco whose only value lay in its water source and two rough roads leading east to the Paraguay River. In August the Paraguayans moved all their operational aircraft—three Wibaults and five Potezes—to Isla Poí, near Boquerón, to support their offensive. Meanwhile, the Bolivian aircraft remained 340 miles away.

On September 9 the first aerial combat of the war occurred when a Bolivian Vespa and two Scouts caught a pair of Paraguayan Potez 25s as they were bombing Boquerón. One of the Scouts, flown by Major Jordán, bounced a Potez and badly wounded its pilot, 1st Lt. Emilio Rocholl. Nevertheless, Rocholl’s observer, 1st Lt. Román García, took control of the plane and maintained close formation with the other Potezes as they flew at treetop level, keeping their attackers at bay until they returned to Isla Poí. In the end, Boquerón fell into Paraguayan hands and the Bolivians were expelled from the central Chaco.

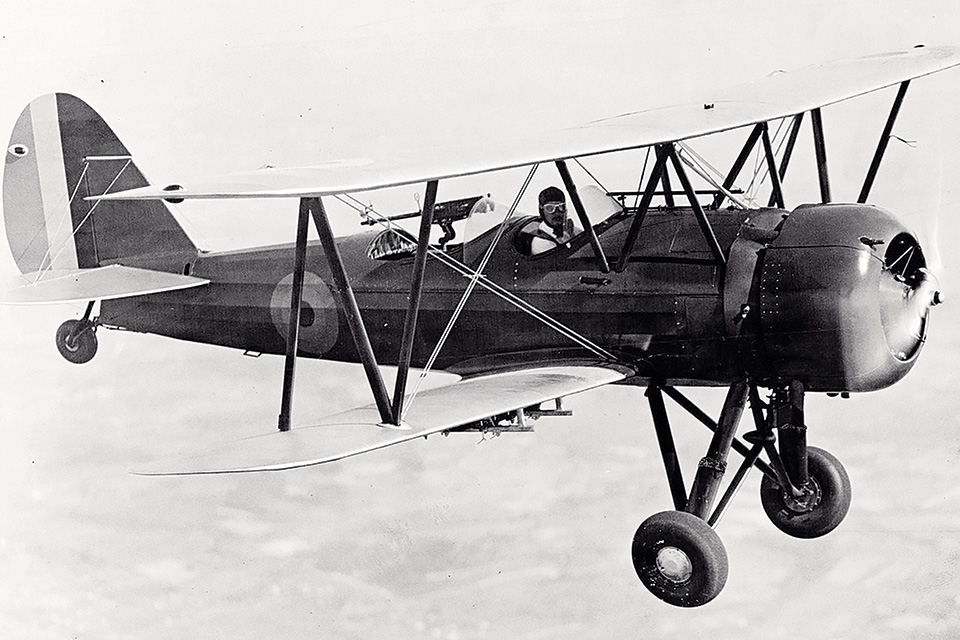

In late 1932 each of the warring countries received a new batch of airplanes that would dominate the Chaco sky for the rest of the conflict. Between October and December, the Paraguayans took delivery of eight new Potez 25 TOEs, which had bigger fuel tanks for longer range. The surviving three Potez 25A.2s were sent to Asunción for refit, while the four remaining Wibaults were relegated to home air defense. Also, in January-March 1933 Paraguay received five Fiat CR.20bis fighters, which formed the 11th Fighter Squadron, “Los Indios” (The Indians).

Beginning in December the Bolivians imported up to eight Curtiss-Wright Model 35A Hawk II fighters and 18 CW-14R Osprey fighter-bombers, the latter of which they constantly used, even as two-seat fighters, while rarely deploying the Hawks. In January they fielded 12 combat planes in two squadrons. The Bolivians retired their worn-out Breguets and Vespas from frontline service in April and began withdrawing their Scouts around July.

The older types still had a historic role to play, though. On December 4, 1932, Paraguayan Potez pilot 1st Lt. Trifón Benítez Vera was attacked by Captain Rafael Pabón Cuevas in one of the remaining Scouts. The Bolivian dived on Benítez and, in a second attack from below in spite of the Potez’s low altitude, hit its fuel tank and killed the observer, Captain Ramón Avalos Sánchez. A third pass killed Benítez and sent the Potez down. Historians used to consider this action the first air-to-air victory scored over the Americas, but in fact that had occurred some four months earlier during Brazil’s Paulista War. Nevertheless, this was the first shootdown with a fatal outcome.

In January 1933 the Bolivian forces under newly appointed German-born General Hans Kundt focused their efforts on taking Nanawa in the south. When that post was about to be overrun, four Paraguayan Potezes managed to land under enemy fire, carrying 1.6 tons of vitally needed supplies. In the process, three of them were so badly damaged by anti-aircraft fire that they had to be left in Nanawa, though they were later recovered and completely rebuilt in Asunción. The Bolivian Hawks and Ospreys operating over the combat zone were unable to intercept them, probably because of the long distance between their bases and the front.

An Osprey crewed by Captain Arturo Valle Peralta and 1st Lt. José Max Ardiles Monroy was shot down by AA fire on February 25. During the burial ceremony two Bolivian Scouts overflew the area and dropped a wreath of flowers. Not a single shot was fired on them by the Paraguayans.

On June 12 the Bolivians, alerted to the presence of the new Paraguayan Fiats, dispatched five Ospreys, three Hawks and one Scout to destroy them by bombing Isla Poí airfield. Watchtower teams alerted the Paraguayans to the incoming planes, however, enabling them to scramble three CR.20s to defend the aerodrome. The Fiats dived from 8,000 feet on the Ospreys, which broke formation, dropped their bombs and fled. Turning to engage the Bolivian fighters, Lieutenant Ruffinelli attacked one of the Hawks, which took evasive action. Meanwhile the Scout pilot, Major Luis Ernst Rivera, got on the tail of a Fiat flown by 1st Lt. Walter Gwynn, who suddenly went down and crashed. It is possible that Gwynn lost consciousness during the dogfight due to an injury sustained in a Fiat crash the previous week. A Paraguayan with blonde hair and blue eyes of Welsh parents, Gwynn had been advised to stay in the hospital, but he declared that “with so many Paraguayan soldiers fighting on foot, a pilot cannot be in bed in the meantime.”

After the June 12 action there was a long pause in air-to-air encounters, but aircraft continued to carry out ground attacks and artillery-correction missions. In July most of the Bolivian forces facing Nanawa were enveloped and destroyed by a massive Paraguayan counterattack led by Estigarribia through the overextended Bolivian left flank, similar to what would later befall the Germans at Stalingrad late in 1942. After suffering 10,000 casualties, Kundt resigned his command and the Bolivians evacuated all of the southern Chaco.

July 8, 1934, saw one of the most intense air actions of the war when four Paraguayan Potez 25s struck Ballivián airfield on the Pilcomayo River, where they caught eight Ospreys on the ground. The raiders made two passes over the airfield, destroying or damaging several Ospreys. As they were making their third firing pass, however, the Paraguayans were attacked by two Ospreys and two Hawks that had arrived from another airfield. During the ensuing battle, Captain Job von Zastrow, manning the twin machine guns in one of the Potezes, claimed an Osprey piloted by Major Eliodoro Nery (though the Bolivians said Nery was killed in a training accident nine days later). Meanwhile, Potez observer 2nd Lt. Fabio Martínez was wounded, as was the crew of another Potez, 2nd Lts. Arsenio Vaesken and Cesar Corvalán Doria, who were nevertheless able to control their stricken aircraft and maintain a tight formation. Consequently, their defensive fire damaged an Osprey piloted by Lt. Alberto Alarcón and Captain Juan Antonio Rivera’s Hawk, compelling them to abandon the fight. The remaining Hawk pilot, Sub Lt. Carlos Lazo de la Vega, now facing the combined fire of eight machine guns, also departed. The Paraguayans’ success was so thorough that July 8 was declared their national Aviation Day.

On August 12 a Potez was on a reconnaissance mission near Fortin Florida in the northern Chaco when its crew spotted a Bolivian Osprey taking off to attack them. The Potez dived and began its standard zig-zagging maneuver at treetop level. The Paraguayan observer, 1st Lt. Rogelio Etcheverry, fired at the Osprey, but its pilot evaded and hit the Potez’s fuselage on his first pass. As the Potez pilot reduced his speed to almost stalling, the Osprey made a second pass, damaging its wings. But when the Osprey came on for a third pass, Etcheverry held his fire until the enemy was just 250 yards away and then opened up. Suddenly, the Osprey stopped firing, smoked heavily, turned to the left and crashed in a wood. After the heavily damaged Potez landed, Etcheverry learned to his surprise that he had killed the war’s first victor in air-to-air combat, then-Major Pabón.

The Bolivians’ aircraft losses were quickly made up as they imported more reinforcements in September and October. The nine Curtiss-Wright Cyclone Falcon bombers and three Junkers K-43 bombers equipped the “Punta de Alas” (Wingtips) Squadron.

On November 14 the Battle of Ballivián ended in a massive Paraguayan victory, with the Bolivians suffering 15,000 casualties and being expelled from the Chaco. As a small consolation, on December 11 two Bolivian Hawks flown by Lieutenants Alberto Alarcón and Emilio Beltrán shot down a Potez piloted by 2nd Lt. Vaesken that was exploring the El Carmen area. The Bolivians damaged the Potez’s engine, so Vaesken dived and landed, surviving but seeing his plane completely destroyed. To balance this, on November 26 AA fire downed a Bolivian Hawk and killed its pilot, Lieutenant Lazo de la Vega, as he was flying a recce mission in Puesto Central.

In December 1934 Bolivian aviation was organized into the 1st Aviation Combat Group, led by Major Jordán from Villa Montes, and the 2nd Aviation Combat Group, under Major Ernst in Charagua, each with a fighter and a bomber squadron adding up to some 11-14 planes at any one time. By then operational Paraguayan air strength had been reduced to four Potezes and two Fiats based at Camacho.

With all their air assets placed near the front this time, the Bolivians were able to repulse Estigarribia’s assault in Villa Montes, near the oil wells, but not without paying a price. On January 12, 1935, a Bolivian Falcon flown by Lieutenant Aurelio Roca Llano was downed by AA fire over the Paraguayan lines, and on the 18th another Falcon piloted by Lt. Alberto Montaño shared the same fate. Ironically, both shootdowns were made by Oerlikon guns of Bolivian origin captured by the Paraguayans.

In February-March the Paraguayans moved farther north, bypassing Villa Montes and cross-ing the Parapetí River to carry the war into Bolivia proper. They took Charagua after four Potezes destroyed the 2nd Bolivian Corps headquarters, but were driven back into their own territory by a massive counterattack in May. During this time the Bolivians created the 3rd Aviation Combat Group with two Hawks and an Osprey at Puerto Suárez, in the northeast. Nevertheless, when the battle ended, the Bolivian 1st and 2nd groups were reduced to just two Hawks and one Osprey each by attrition and by transferring aircraft to other theaters.

By April 1935 both sides were in a stalemate, unrelieved by a Bolivian diversionary attack on the other side of the Chaco that had failed by May 25. Paraguay had occupied nearly 68,000 square miles, but at a cost of 36,000 dead and 3,800 captured, while Bolivia had lost 67,000 dead, 21,000 captured and 10,000 deserted, mainly to Argentina. Both sides had suffered as many casualties to disease, insects and venomous snakes as to combat. Mutually exhausted, both parties arranged an armistice that went into effect on June 12.

In a treaty signed in Buenos Aires on July 21, 1938, Paraguay was awarded three-quarters of the disputed territory, but Bolivia was given an outlet to the Atlantic Ocean via the Paraguay River. With that, the war in—and above—what both sides came to call the “Green Hell” was over at last.

Javier Garcia de Gabiola writes from Spain, where he works as a lawyer in a multinational company. A passionate military and aviation historian, he has published some 50 magazine articles as well as his first book, Paulista War: The Last Civil War in Brazil, 1932. Further reading: Aircraft of the Chaco War 1928-1935, by Dan Hagedorn and Antonio L. Sapienza; The Green Hell, by Adrian J. English; and The Chaco Air War 1932-35, by Sapienza.

This feature appeared in the July 2021 issue of Aviation History. Don’t miss an issue, subscribe today!