British Admiral Thomas Cochrane excelled in the navies of three nations, but his combative nature nearly made him a footnote in naval history

On May 6, 1801, sailing ships waged a maritime David and Goliath battle in the Mediterranean off Barcelona, Spain. The combatants were the diminutive British Royal Navy brig HMS Speedy and the vastly larger and much better armed Spanish xebec-frigate El Gamo. Described by its captain, Thomas, Lord Cochrane, as “a burlesque on a vessel of war,” Speedy was smaller than a rich man’s yacht at scarcely 78 feet in overall length and not quite 26 feet across the beam. Its armament was so light that Cochrane once strode the quarterdeck in jest with an entire broadside of shot in his coat pockets.

That Speedy found itself engaged with a far superior opponent was not bad luck—it was intentional on Cochrane’s part. His superiors had ordered the captain to engage French and Spanish vessels operating in the western Mediterranean during the French Revolutionary wars. Cochrane and crew had proved so successful that the Spanish had resolved to set a trap for the British warship. Cochrane learned of the plot, and when several enemy gunboats sought to bait the brig toward Barcelona, he obligingly followed. The resulting battle was one of many that ultimately earned Cochrane the epithet “The Sea Wolf.”

Cochrane became one of the most brilliant naval commanders in the Age of Sail in spite of himself. He was by all accounts obstinate, self-righteous, self-promoting and irritating, even to friends. According to one writer, he lacked political subtlety, was impatient, intemperate in his language, paranoid and continually upsetting superiors. In short, it seemed Cochrane was his own worst enemy.

Lord Cochrane was born on Dec. 14, 1775, in the council area of South Lanarkshire, Scotland, the son of Archibald Cochrane, the ninth Earl of Dundonald (the term “Lord” was a courtesy title given to the heirs of peers). The title was virtually the only thing Cochrane inherited. His own father was impoverished, as over several generations the family lands had been squandered, foreclosed on or seized by the Crown. “I never inherited a foot,” Cochrane wrote of his ancestors’ once extensive holdings.

Though lacking in wealth, the family’s long history of military service meant the young man did not lack influential contacts, including distinguished peers and senior officers. Having served in both the British army and Royal Navy, his father vigorously discouraged Thomas from a naval career and secured him an army commission. The younger Cochrane obeyed his father’s wishes—but only for a time. Consequently, Thomas was older than his peers when he entered the Royal Navy as a 17-year-old midshipman in 1793 as Britain was pulled into the French Revolutionary wars.

On his first vessel, the 28-gun frigate Hind, Cochrane learned the seaman’s trade from both the vessel’s captain—his uncle Alexander Cochrane—and the curmudgeonly 1st Lt. Jack Larmour, a former enlisted man promoted to officer for his seafaring skills. Cochrane proved an apt student, earning Larmour’s respect.

Britain was fully at war by the time Cochrane went to sea. His first and only cruise on Hind took him to the Norwegian fjords looking for French privateers. As no enemies presented themselves, the six-month voyage served as more of a training cruise for the midshipman.

Returning from Norway, Cochrane transferred with his uncle to the 38-gun frigate Thetis. He spent the next five years patrolling the waters off North America, stopping and searching U.S.-flagged vessels. By 1796 Spain and France had allied against Britain, while the United States remained neutral in the French Revolutionary wars. Regardless, the British considered any cargoes bound for Spain or France to be contraband and subject to seizure, while any British sailors found on American ships were also seized and impressed into service aboard Royal Navy ships. Cochrane was sympathetic to the U.S. government’s complaints about the latter practice, as impressment might leave a ship dangerously shorthanded.

In 1798 Cochrane was assigned to the Mediterranean as a lieutenant aboard the 90-gun second-rate Barfleur, helmed by Vice Adm. George Elphinstone, 1st Viscount Keith, second-in-command of the British Mediterranean Fleet. Serving under a despotic first lieutenant, Cochrane soon faced a court-martial for insubordination, an accusation he hotly disputed. The court was sympathetic, and Lord Keith privately told him to be more careful in the future.

It was not the last time Cochrane would find himself in legal hot water. The accusation did not prevent his promotion to commander and appointment to Speedy in March 1800, with orders to harass the French and Spanish fleets in the Mediterranean. That assignment, and his duel with El Gamo, set him on the path to maritime fame.

Cochrane’s decision to follow Spanish “bait ships” toward Barcelona soon brought him face to face with the 32-gun El Gamo, which opened fire on Speedy and hoisted its colors as soon as it came within range.

Realizing his ship’s 14 four-pounders were no match for the Spanish frigate’s mixture of 8- and 12-pounder guns and 24-pounder carronades in either range or hitting power, Cochrane fell back on a time-honored naval tactic—deception. He ordered the American flag hoisted atop Speedy’s aft mast, even while directing the helmsman to steer for the enemy frigate. Confounded by the appearance of the Stars and Stripes, the Spanish captain hesitated just long enough for Cochrane to change tack, hoist British colors and evade El Gamo’s first broadside.

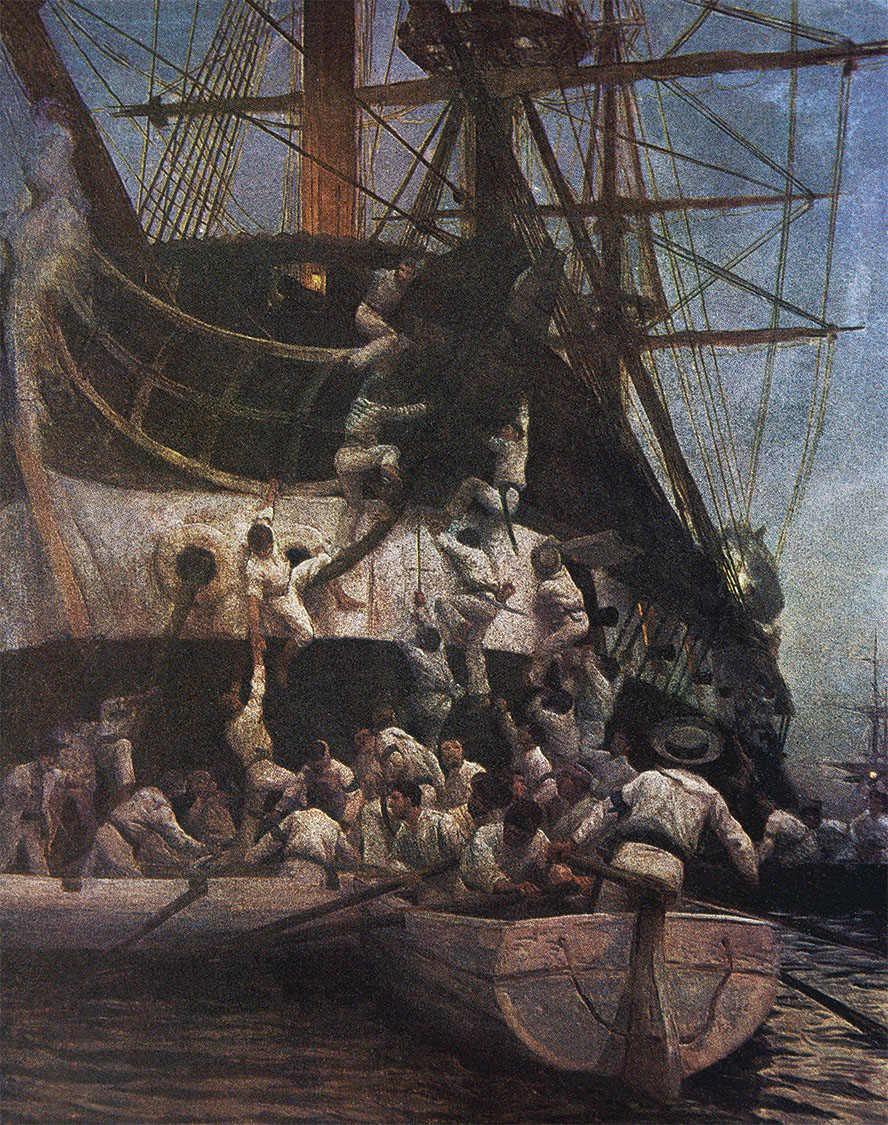

Skirting a second broadside, the nimble British brig ran in close, so close that Speedy’s yardarms became entangled in the frigate’s rigging, as Cochrane intended. At such close range the enemy gunners were unable to depress their weapons low enough to bear on the British attacker. But Speedy’s guns, triple-loaded with shot and elevated, raked the Spaniard’s main deck with terrible effect, killing both their captain and boatswain. The Spanish crew attempted to board the attacking vessel, but Cochrane sheered off just far enough to defeat that maneuver, having his gunners fire another broadside and his musketeers pick off enemy sailors. Twice more the Spanish crewmen sought to board Speedy, only to face the same punishment.

Cochrane realized the seesaw fight could not last indefinitely. Although the Spaniards could not depress their guns to damage Speedy’s hull, their chain shot was ravaging the sloop’s rigging. Faced with the increasing danger of being dismasted and captured—and knowing the Spanish would allow no quarter—Cochrane told Speedy’s crew they must reverse the tables and capture the enemy frigate. The bold British captain soon gave the order to board.

El Gamo’s surviving crewmen were initially stunned so few enemy sailors would attempt a boarding in the face of overwhelming opposition. Their confusion only increased when, in the midst of the pitched battle for control of the frigate’s decks, Cochrane ordered the Spanish flag struck. Assuming their own officers had surrendered the vessel, the Spaniards lay down their arms, ending one of the most bizarre and unequal ship-to-ship battles of any war. (The action inspired a scene in the 2003 Napoléonic wars epic Master and Commander in which British Captain Jack Aubrey, played by Russell Crowe, similarly entangles his ship with that of a French opponent and boards it. The character of Aubrey is based on both Cochrane and fellow Royal Navy commander William Woolsey.)

In the 13 months following the capture of El Gamo, Cochrane went on to seize, burn or drive ashore upward of 50 enemy ships. Deception remained a key part of his playbook. Once when pursued by a superior enemy frigate off the Spanish coast, he had Speedy painted in imitation of a known Danish brig and hoisted the Danish colors. To complete the ruse he had a Danish crewman appear on deck in his own nation’s uniform. When eventually hailed by a boarding party from the enemy vessel, the Dane hollered out that the plague was ravaging the crew. Naturally, the Spaniards thought better of boarding the “infected” ship, veered off and wished them a good voyage.

It was none other than Napoléon, vexed by Cochrane’s exploits at the helm of Speedy, who nicknamed its captain Le Loup des Mers—“The Sea Wolf.” The cruise ended abruptly on July 3, 1801, when a trio of French warships gave chase and finally captured Speedy. The lead French captain acknowledged his admiration for Cochrane by refusing to accept the British officer’s sword. Treated well by their captors, Cochrane and his crew were exchanged within days for a similar number of French prisoners. The following spring Britain and France signed the Peace of Amiens, suspending hostilities.

Though Cochrane’s victories at sea made him hugely popular with the British public, his superiors at the Admiralty were not amused. They had to contend with the captain’s tirade of complaints, foremost that he was being cheated out of rightfully earned prize money.

At the time whenever a Royal Navy warship captured an enemy vessel, a prize crew would take possession of the captured ship and sail it to a British-held port. In theory, agents would then sell the ship and its contents, the victorious captain and his crew receiving shares of the profits realized. Though Cochrane received many thousands of pounds sterling for ships he captured, he routinely complained of being cheated by corrupt agents, politicians and even senior naval officers. In frustration, he later stood for and was elected to Parliament, making the reform of the prize system a priority during his time in office.

Cochrane’s contentious personality and arrogance did not endear him to those in power. The slights, insults and injustices he suffered—both real and imagined—made him less than polite in his dealings with superiors. His belligerent tendencies made an especially powerful enemy of First Lord of the Admiralty John Jervis, 1st Earl of St. Vincent. While many of Cochrane’s self-inflicted wounds healed in time, this one did not. The upstart captain so irritated Lord St. Vincent that Cochrane, on losing Speedy, found himself ashore with little prospect of getting another ship, at least until the resumption of war in 1803. By then Cochrane’s persistent apologies, coupled with pleas on his behalf from influential relatives and friends, had prompted St. Vincent to relent. Even then, however, Cochrane complained that Arab, the 22-gun former French privateer given him to command, was small, slow, barely seaworthy and scarcely maneuverable. Cochrane compared it to a collier. To add insult to injury, St. Vincent had Arab dispatched northeast of the Orkney Islands to protect the fisheries—in waters where there were no fisheries to protect.

In 1804 the incoming government forced St. Vincent to resign as first lord. His successor, Henry Dundas, 1st Viscount Melville, was more sympathetic to Cochrane and gave him command of Pallas, a new 32-gun frigate. Over the next five years Cochrane resumed prowling the Mediterranean with astounding success, though in surprisingly changeable circumstances. In 1808 Napoléon invaded Spain and installed his brother, Joseph Bonaparte, on the Spanish throne. With that Britain’s longtime Spanish enemy became its ally in the resulting Peninsular War.

Then in command of the 38-gun Imperieuse, a captured Spanish frigate, Cochrane planned and conducted amphibious operations to disrupt French communications and interdict troop movements. Amid the Battle of the Basque Roads in April 1809 he led a flotilla of fireships and bomb vessels against the anchored French fleet. Although the operation left all but two of the fleeing enemy vessels grounded, Adm. James Gambier squandered the opportunity to destroy the entire French fleet, seemingly out of professional jealousy. Then MP Cochrane, though knighted for his part in the battle, later refused to join in a motion expressing the country’s gratitude toward Lord Gambier. The admiral had failed in his duty, Cochrane stated publicly of his superior, so no expression of thanks was required. Gambier demanded a court-martial to clear his name and was acquitted.

For his part Cochrane continued to create implacable enemies both political and personal. He claimed such men conspired to publicly humiliate him, bankrupt him, strip him of his knighthood, expel him from Parliament, drum him out of the Royal Navy and imprison him. His enemies got their chance to do just that amid the Great Stock Exchange Fraud of 1814. Although charges that Cochrane had been involved in the scandal were weak, he was convicted, sentenced to a year in prison, fined £1,000 and ordered to stand in the pillory. True to his predictions, he was also expelled from Parliament, dismissed from the navy and stripped of his knighthood.

But those who thought they had finally consigned a chastened Cochrane to a sad and broken life ashore were soon proved wrong.

A humiliated and unemployed Cochrane left Britain in 1818 and immigrated with his family to Chile, then embroiled in a war of independence from Spain. He had come at the behest of revolutionary leader Bernardo O’Higgins, who granted Cochrane citizenship and made him vice admiral of the newly formed Chilean navy. The admiral promptly reorganized the small force and undertook blockades and coastal raids against Spanish-held ports and fortifications.

In 1820, with only three ships and 310 men, Cochrane led an amphibious assault on the port of Valdivia, a heavily fortified supply depot vital to the Spanish army opposing Chilean independence. Landing his small force on the night of February 3, Cochrane took the Spaniards by surprise, quickly capturing two forts and forcing the capitulation of two others. The next day the remaining Spanish forts surrendered.

Assigned that summer to escort Chilean Gen. José de San Martín’s expedition in support of Peruvian independence, Cochrane and his squadron blockaded the port of Callao, in which a Spanish squadron lay at anchor. The enemy flagship was Esmeralda, a 44-gun frigate, supported by three smaller warships with 47 guns between them. Ringing the squadron were three dozen gunboats and armed merchant ships. A floating chain of logs obstructed the narrow harbor entrance, while heavy artillery in overlooking fortresses and batteries stood ready to defend the Spanish ships.

Undeterred, the venturesome Cochrane resolved to capture or destroy the Spanish squadron. His meticulous plan centered on the stealthy nighttime boarding and seizure of Esmeralda. Handpicking a strike force of 240 sailors and marines, he drilled the troops relentlessly. By November 5 all was ready. That afternoon, to lull the Spaniards into believing the blockade had failed, he had two of his ships visibly weigh anchor and sail off. Meanwhile, he anchored his flagship, the Russian-built 48-gun frigate O’Higgins, out of view behind an island.

That night Cochrane led his flotilla of 14 small boats to the attack. Their oars wrapped in canvas, the men silently rowed up alongside Esmeralda, swarmed aboard and took its crew by surprise.

The Spaniards regrouped, and a fierce and bloody fight ensued. Cochrane himself was shot in the thigh and had to direct the fight while seated. But the issue was never in doubt. When the firing ceased, Cochrane ordered Esmeralda’s new Chilean crew to sail home with their prize. O’Higgins considered the flagship’s capture indispensable to Chilean independence, as it effectively ended the Spanish presence in the Pacific.

Despite accolades from the revolutionary leader, Cochrane’s acerbic personality led to difficulties with Chilean officials, particularly San Martín, whom the admiral accused of claiming credit for the capture of Esmeralda, as well as failing to pursue the fleeing Spanish and intending to establish Peru as his personal kingdom. The general, in turn, accused Cochrane of stealing $400,000 intended for San Martín’s army. Cochrane—who had indeed seized the money from a schooner dispatched from Peru by San Martín—claimed the amount taken was $283,000 and represented only a portion of the pay and prize money owed his Chilean crewmen. The hostility and distrust engendered by Cochrane forced him to leave Chile in search of new opportunities. That search led him to other nations and other navies.

In January 1823, accompanied by his long-suffering wife and children, Cochrane left Chile for Brazil, and on March 21 he took command of that nation’s fledgling navy. Also chafing under colonial rule, Brazilians were fighting for independence from Portugal. Spearheading the revolution was the recently coronated Emperor Pedro I—who, bizarrely enough, was prince regent of Portugal.

Near Salvador, Bahia, on May 4 Cochrane first confronted the Portuguese fleet. Blockading the enemy in port, he forced their evacuation and harassed their retreating ships all the way back to Europe. On returning to Brazil, Cochrane bluffed the Portuguese garrison at Maranhão into surrender by claiming a vast Brazilian invasion fleet was en route. The capture of Maranhão and Belem, using the same bluff, resulted in the de facto independence of Brazil. For his efforts Cochrane was proclaimed Marquess of Maranhão by Pedro I.

As in Britain and Chile, however, Cochrane’s personality ultimately got him into trouble in Brazil. After a familiar dispute over pay and prize money, and accusations of theft of public funds, Cochrane returned to Britain in 1825. Ever restless, he soon made his way to Greece to assist that country’s rebellion against the Ottoman Turks. Two years later, when the British, French and Russians intervened to end the war, Cochrane again returned to Britain.

On his father’s death in 1831, Cochrane became the 10th Earl of Dundonald. The following spring William IV—known as the “Sailor King” for his youthful service in the Royal Navy—pardoned the disgraced lord and restored him to the service as a rear admiral. The ever contentious Cochrane refused to take a command until his knighthood was restored. It took 15 years, but in 1847 Queen Victoria reappointed him to the Order of the Bath. A year later Cochrane returned to service in the Royal Navy as commander in chief of the North America and West Indies Station, where he had served as a young midshipman. During the 1853–56 Crimean War the Admiralty considered him for command of the Baltic Fleet, but ultimately passed him over for fear he would be too rash.

In 1854 a fully redeemed Cochrane was appointed to the honorary office of rear admiral of the United Kingdom. By then he was in decline and suffering from depression. On Oct. 31, 1860, the 84-year-old veteran of three navies died following surgery for kidney stones. A half century earlier the prince regent (future King George IV) had had Cochrane’s knight’s banner publicly removed from Westminster Abbey. The banner was restored the day before the admiral’s funeral and interment in the abbey.

Notwithstanding his acrimonious personality and frequent public and private confrontations, Cochrane was a brilliant naval tactician and gifted operational commander. He was also a technological innovator, having designed a better convoy lamp and a transportable gunboat for use in coastal raids, patented the first successful tunneling shield, supported steamship development, and proposed the combined use of fireships and poison gas when attacking enemy harbors.

Though his two autobiographies—Narrative of Services in the Liberation of Chili, Peru and Brazil From Spanish and Portuguese Domination (1859) and The Autobiography of a Seaman (1860)—are clearly self-serving and intended to even the score with his old enemies, the Sea Wolf was undeniably one of the most successful and extraordinary British seamen of his age. MH

Jerome Long is a former military history instructor at the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College at Fort Leavenworth, Kan. For further reading he recommends Cochrane: Britannia’s Sea Wolf, by Donald Thomas; and David Cordingly’s Cochrane: The Real Master and Commander and Cochrane the Dauntless: The Life and Adventures of Admiral Thomas Cochrane, 1775–1860.

This article appeared in the November 2021 issue of Military History magazine. For more stories, subscribe and visit us on Facebook: