A handful of critical decisions altered the course of the 1862 Seven Days Campaign

The Seven Days Campaign, fought June 25–July 1, 1862, prevented the Army of the Potomac from capturing the Confederate capital of Richmond, Va., at a critical junction early in the Civil War; established Robert E. Lee as an army commander, which would be an instrumental factor in extending the war for another three years; and forced the Lincoln administration to grapple with the issue of emancipation. The fighting and maneuvering that raged that summer from north of Richmond to 16 miles southeast along the James River unfolded as it did because of 16 critical decisions made before, during, and after the battles by commanders in both armies and at all levels. Of these decisions, three were strategic, four operational, eight tactical, and one personnel. Four were national-level decisions, nine army-level, one wing-level, and two division-level. Seven were made by Union commanders, nine by Confederate commanders. All were implemented by the thousands of soldiers in the Army of Northern Virginia and the Army of the Potomac.

1. McClellan Decides on a Turning Movement

Army-Level Strategic Decision

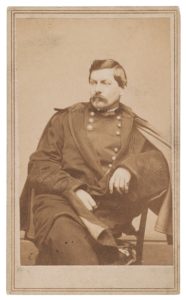

Under pressure to begin operations in the spring of 1862, Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan, commander of the Army of the Potomac, developed a plan using Union naval power to move his army from the vicinity of Washington, D.C., 87 miles south to Urbana, Va. In March, General Joseph E. Johnston’s Confederate army retreated south from Centreville, Va., to the Rappahannock River, about 36 miles, which blocked McClellan’s intended Urbana movement.

The Union general then modified his plan and moved the army to Fort Monroe on the tip of the Virginia Peninsula. Shifting the center of fighting in the Eastern Theater to the Peninsula put the Confederate capital in jeopardy of capture if sufficient forces could not be redeployed in time for its defense. The series of events set in motion by this decision led to the Seven Days.

2. McClellan Decides to Besiege Yorktown

Army-Level Tactical Decision

By April, McClellan had approximately 50,000 men, with more arriving every day—enough to move against the Confederate positions at Yorktown and the Southern army’s defensive line across the Peninsula. Confederate Maj. Gen. John B. Magruder, who commanded 13,000 troops, skillfully used his soldiers to bluff McClellan into thinking he had a significantly larger force. McClellan decided to lay siege to the Yorktown defenses, putting heavy artillery in place from mid-April to May 2, which allowed Johnston time to shift a significant portion of his army from the Rappahannock to the southern part of the Peninsula. The Confederate position at Yorktown was abandoned the night before McClellan’s siege artillery was set to open fire. Because of his decision, McClellan lost the operational advantage gained by moving to the Peninsula. Sufficient Confederate forces were now deployed between his army and Richmond and closed the once-open road to the capital.

3. McDowell Is Diverted

National-Level Operational Decision

As McClellan began moving his army to the Peninsula, President Abraham Lincoln directed Maj. Gen. Irvin McDowell’s 33,510-man 1st Corps to remain near Washington for the defense of the capital. When Johnston transferred his army from the Rappahannock River to the Peninsula, McDowell’s corps moved to just across the Rappahannock from Fredericksburg. In mid-May, he was ordered to shift farther south toward Richmond and work in conjunction with McClellan’s army.

Major General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson, however, began his Valley Campaign shortly thereafter. In response, McDowell was ordered to concentrate, along with two other commands, near Strasburg in an attempt to cut off Jackson while he was in the northern Shenandoah Valley. That attempt was unsuccessful, and a large portion of McDowell’s force spent wasted time marching to the Valley and then back to Fredericksburg. As a result, McDowell’s corps did not make contact with the Army of the Potomac’s right flank. Such a juncture would have extended the Union lines at Richmond to the northwest and west, which would have precluded the turning movement Lee planned against McClellan’s right rear area, supply line, and base. It would have also blocked Jackson from joining Lee, as he did in late June.

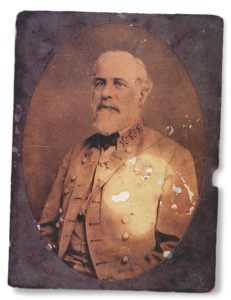

4. Davis Decides on Lee

National-Level Personnel Decision

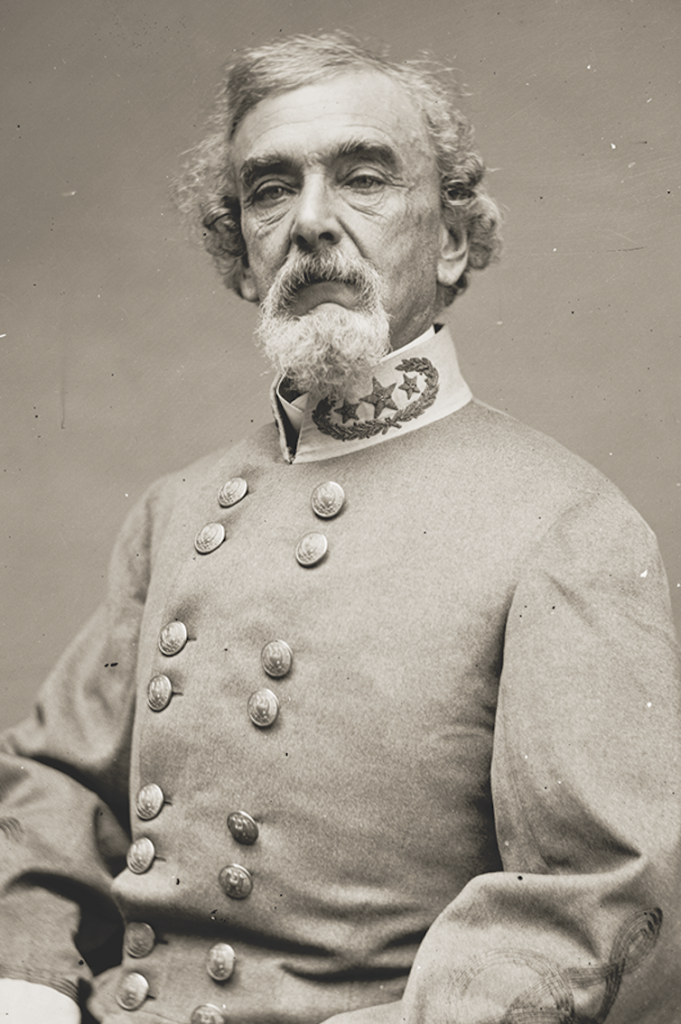

name Army of Northern Virginia on his new command and

moved to the offensive. (The Gilder Lehrman Collection)

After abandoning the Yorktown defenses, Johnston withdrew gradually up the Peninsula while conducting a delay. On May 31, he attacked a portion of the Union army at Seven Pines (Fair Oaks). During the battle, Johnston was severely wounded and evacuated. Confederate President Jefferson Davis needed to appoint a new army commander. He had the option of leaving the army’s second senior officer, Maj. Gen. Gustavus W. Smith in command, appointing General Robert E. Lee, or turning to another general for the position, such as P.G.T. Beauregard or Samuel Cooper. Davis decided on Lee, appointing him commander of the Army of Northern Virginia on June 1.

In two weeks, Lee launched the Seven Days Campaign and determined how the war would be fought in the Eastern Theater for the remainder of the conflict.

5. Lee’s Plan Gets Approved

National-Level Strategic Decision

Upon completion of the Valley Campaign on June 9, Jackson proposed that his command be reinforced from 16,000 to 40,000 troops so he could move north and cross into Maryland and Pennsylvania. The most available for Jackson, however, were 16,500 men, meaning he would still be 7,500 short.

If Jackson had succeeded in following through with his proposal, it would have had a major impact on the war in the East. McClellan would probably have to withdraw part of his army from in front of Richmond and send them back to northern Virginia, but it also meant Lee wouldn’t have sufficient troops to execute the turning movement he was planning. Faced with the two options, Davis sided with Lee and chose not to reinforce Jackson. Lee continued planning his turning movement against McClellan.

6. Lee Decides on a Turning Movement

Army-Level Operational Decision

When Lee assumed command of the Army of Northern Virginia, it was located on the eastern edge of Richmond and besieged by a larger Union army. Knowing that his defenses were vulnerable if McClellan conducted a large siege operation, Lee planned a turning movement around the Union right (north) flank. With the advance of Confederate forces deep into the Union right rear area, McClellan’s supply line would be threatened, particularly his army’s principal supply base at White House Landing on the Pamunkey River, a tributary of the York River. This would turn McClellan’s position and force him into a battle of maneuver.

Lee’s offensive concept would save Richmond and prolong the war.

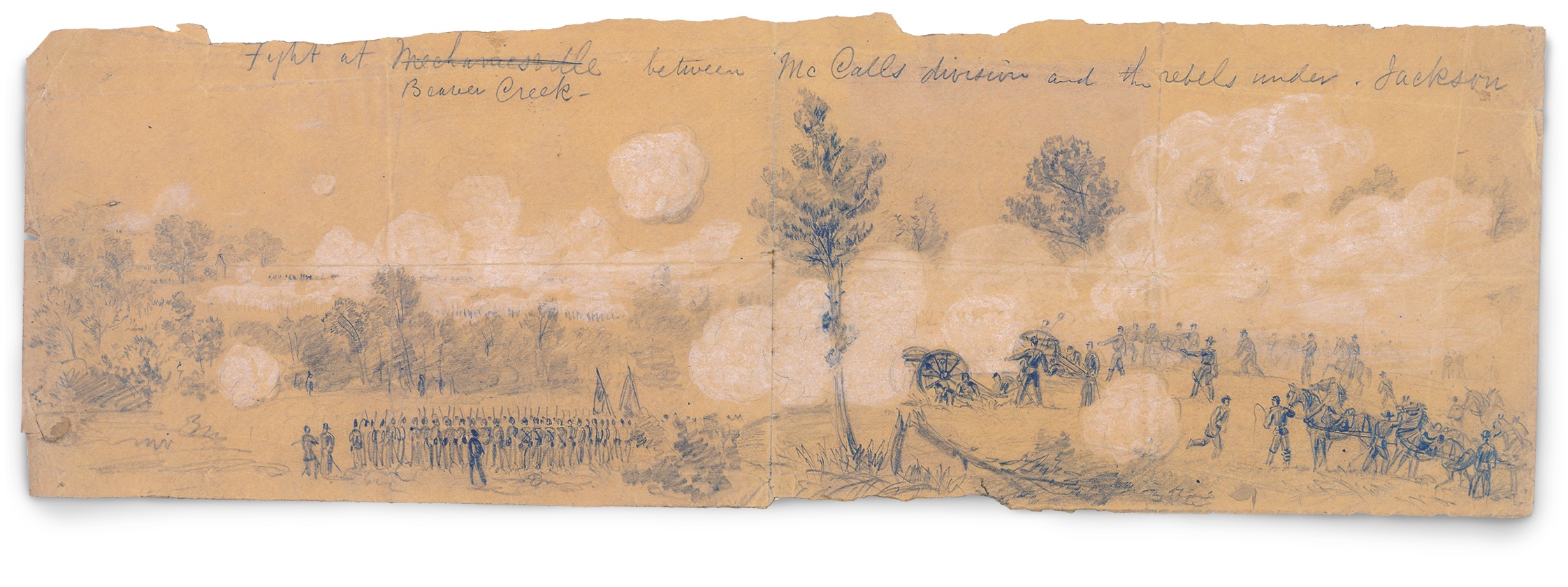

7. A.P. Hill Attacks

Division-Level Tactical Decision

Lee planned to hold a portion of his army in front of Richmond while three divisions were moved farther to the north for the turning movement. These divisions would join with Jackson’s command after it moved from the Shenandoah Valley to Ashland, then south toward the Union right rear area. Major General A.P. Hill’s Division was the leftmost of these three divisions.

When contact was made with Jackson, Hill was to cross the Chickahominy River and attack south to Mechanicsville. That would support Jackson and also clear the way for Maj. Gens. D.H. Hill’s and James Longstreet’s Divisions to cross the Chickahominy. When Jackson failed to reach his planned position by June 26, A.P. Hill made the decision to still launch his attack across the river. That initiated the Battle of Beaver Dam Creek, the first Confederate offensive of the Seven Days. Without Jackson in place, Lee’s plan did not develop as the Confederate commander intended. By taking the initiative, however, Lee disrupted future Federal plans, thereby establishing the tenor of the entire campaign.

8. McClellan Provides Minimal Reinforcements

Army-Level Tactical Decision

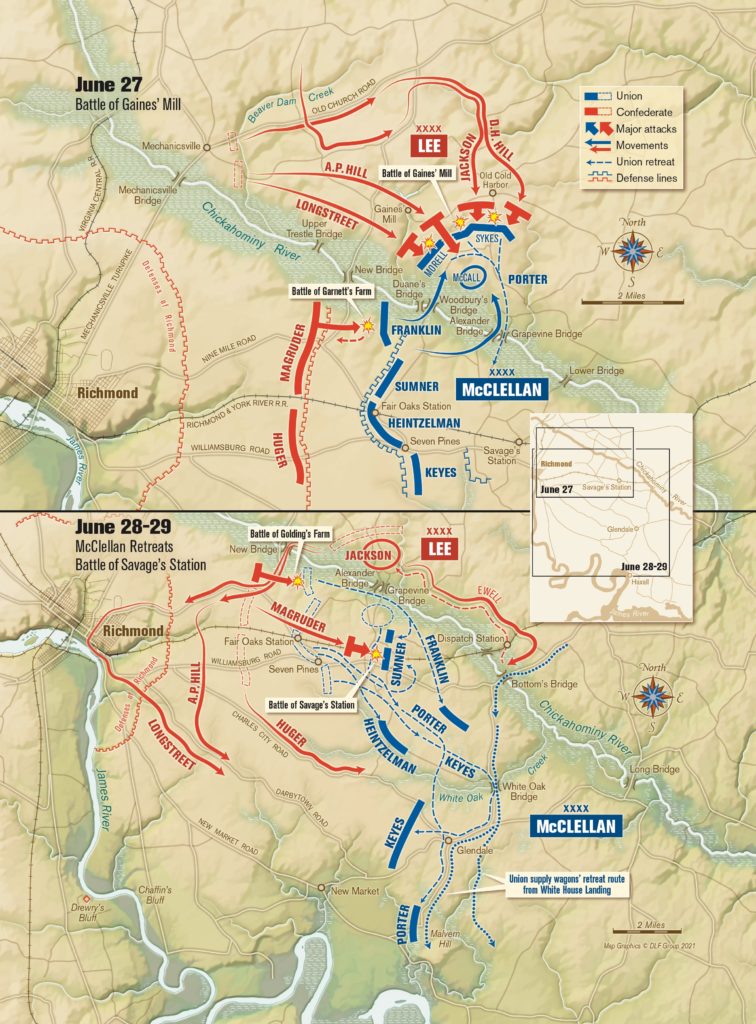

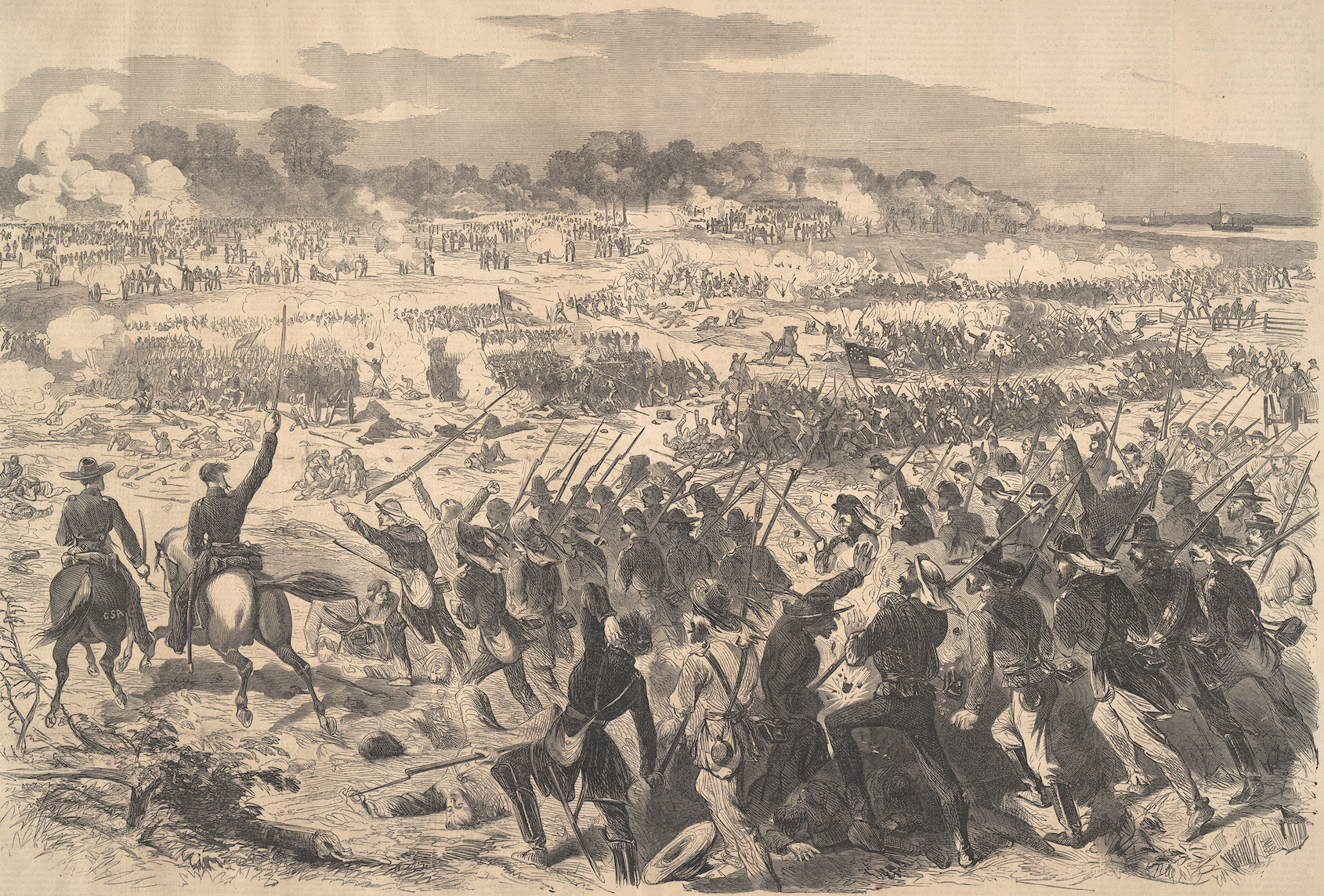

Despite the successful Union defense at Beaver Dam Creek, also known as the Battle of Mechanicsville, McClellan ordered Porter’s 5th Corps to withdraw to the east and establish a defensive position at Gaines’ Mill overlooking Boatswain’s Swamp. Lee soon came up against Porter’s new position.

Throughout the afternoon of June 27, Lee committed all six divisions of his maneuver force in attacks against the Union defenders in the Battle of Gaines’ Mill. This provided McClellan the opportunity to send significant reinforcements north across the Chickahominy to fight a potentially decisive defensive battle and even counterattack the left (east) flank of Lee’s army. McClellan did not do that, however, and late in the afternoon provided only minimal reinforcements that covered the retreat of the 5th Corps after it was forced from its position. McClellan had lost the tactical edge to Lee and would never regain the initiative.

9. McClellan Decides to Retreat to the James River

Army-Level Operational Decision

After Gaines’ Mill, the Union army was concentrated on the south side of the Chickahominy River. McClellan had two options. He could hold Lee along the line of the river and attack with the remainder of his army, the force covering Richmond—an operation that probably would have been successful. Alternatively, he could retreat. McClellan decided to retreat across the Peninsula to the James, which he tried to disguise by calling it a “change of base.”

There he could reestablish a supply base, use the river as a line of supply and communication, and be supported by the Union Navy’s gunboats. The route of retreat began at Savage’s Station, then went southeast, then south across White Oak Swamp, through the crossroads at Glendale, over Malvern Hill, then along the James to Harrison’s Landing.

It was 14 road miles to the James, then seven more miles to Harrison’s Landing for a total of 21 miles. Most roads on the Peninsula ran east and west. There were fewer north-south roads that crossed to the James. Those that existed passed through choke points such as at Glendale. McClellan would be moving a large infantry force with artillery, the artillery reserve, an artillery siege train of 26 heavy guns, more than 3,800 wagons and ambulances, and a herd of 2,518 cattle.

For an army of this size, with the limited road network going across the Peninsula, the retreat would be slow progress. Not all of McClellan’s commanders believed retreat was the right decision. Brigadier Generals Philip Kearny and Joseph Hooker, division commanders in the 3rd Corps, informed McClellan that the Confederate lines in front of Richmond were thinly held and he should launch an immediate attack against them. McClellan refused, and in the ensuing argument Kearny became so aggressive in language toward McClellan that many of those present thought he would be arrested. McClellan had given up any thoughts or pretension of capturing Richmond. For the Army of the Potomac, the Seven Days would turn into a series of successful defensive battles followed by retreats.

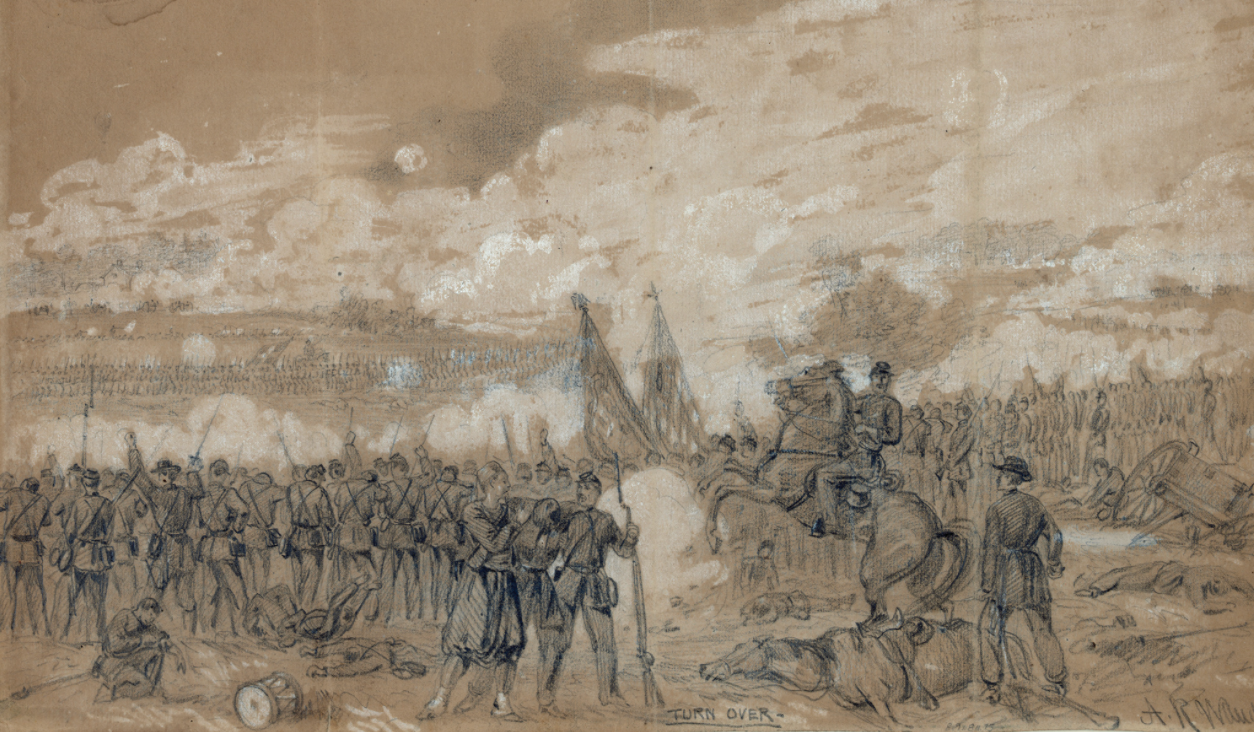

10. Lee Decides on a Pursuit

Army-Level Operational Decision

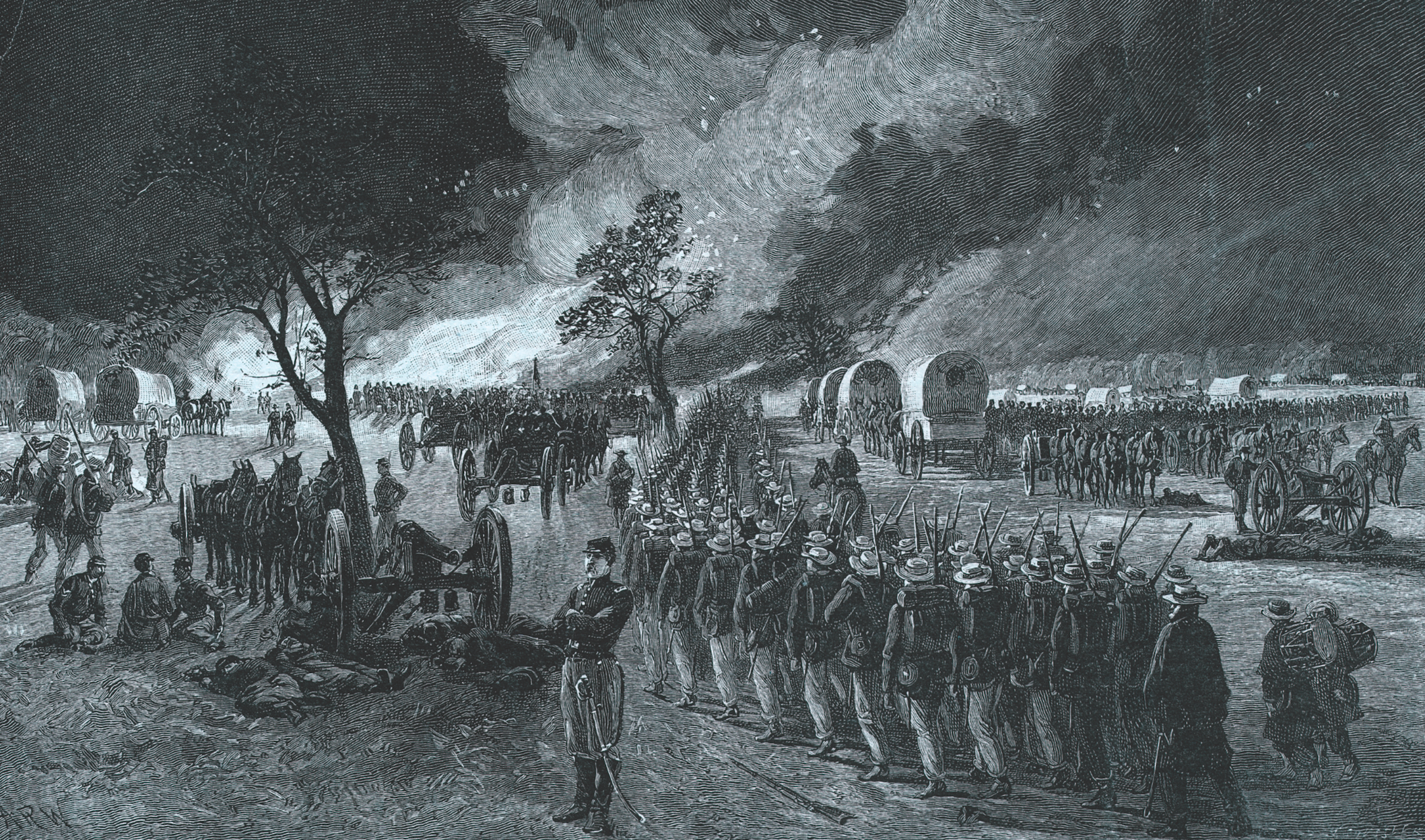

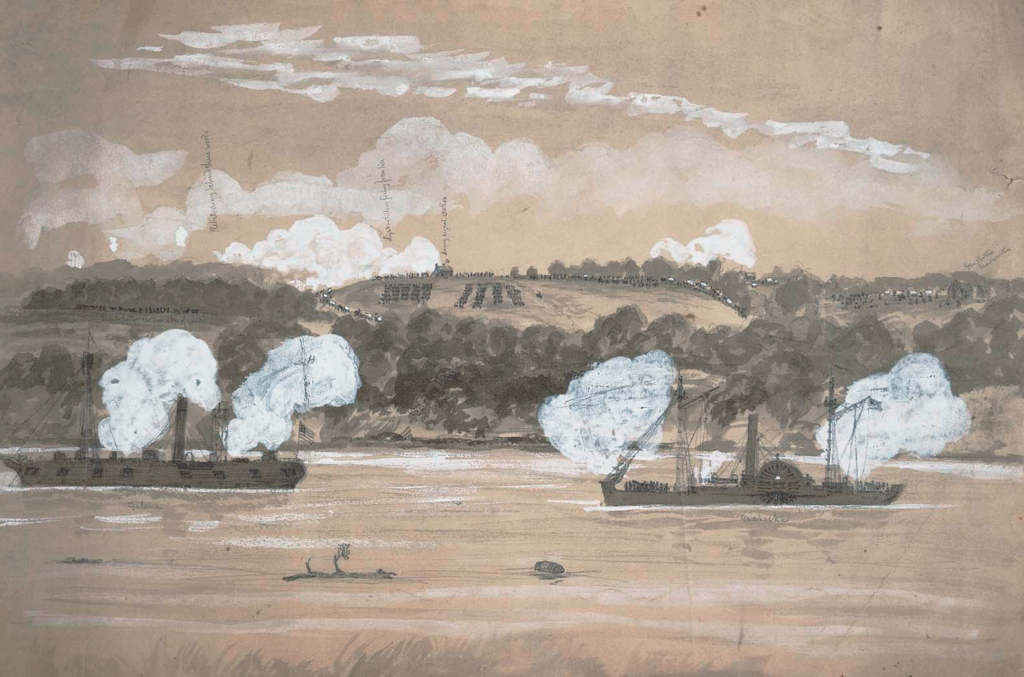

pass by choke points to successfully retreat to the James. Confederate attacks at Golding’s Farm and Savage’s Station failed to break through the Union columns. (Virginia Museum of History and Culture)

On the night of June 27, Porter’s battered 5th Corps retreated to the south side of the Chickahominy and destroyed the bridges after doing so. Lee’s army remained divided into two segments: 1) Magruder’s three-division force and Maj. Gen. Benjamin Huger’s Division holding the defenses of Richmond and 2) six divisions north of the Chickahominy involved in the turning movement. All had lost contact with the Army of the Potomac, and Lee needed 24 hours to determine whether McClellan was retreating south across, and not down, the Peninsula.

Lee had not given up attempting to seriously damage or destroy McClellan’s army. To accomplish that, he decided upon a pursuit. Jackson’s and Magruder’s commands were to apply direct pressure to the Union rearguard to slow its retreat, and did so at the Battle of Savage’s Station. Longstreet, A.P. Hill, and Huger marched to obtain a position at Glendale. If successful, this would block all or a major portion of McClellan’s army from reaching the James River. Lee’s decision continued combat operations for three more days.

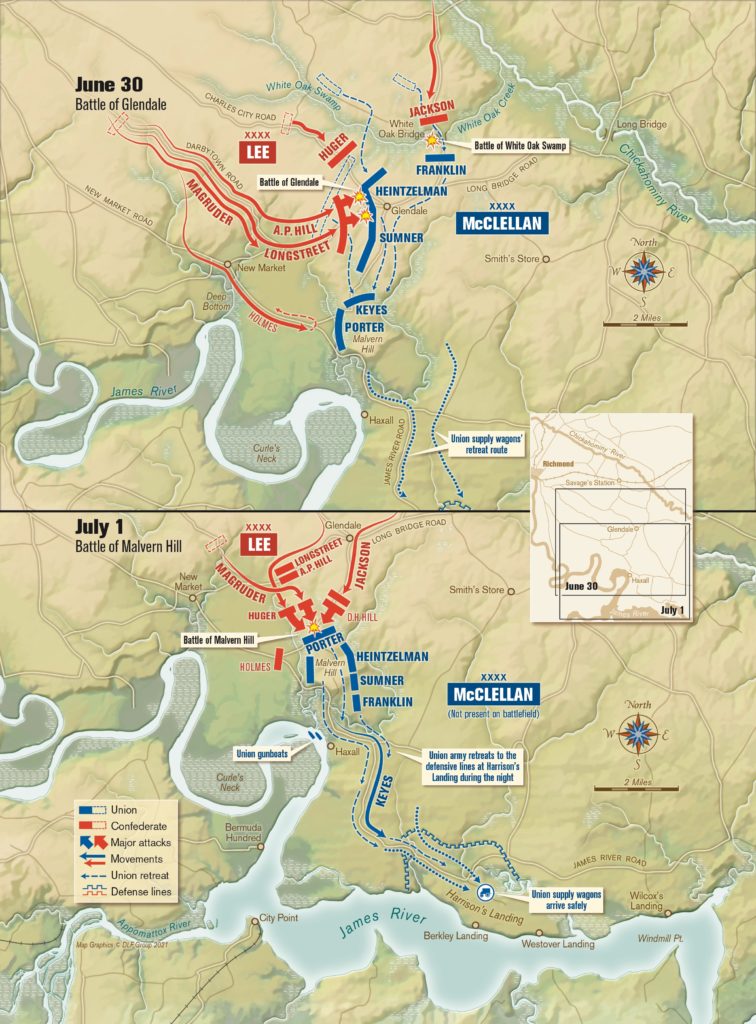

11. Jackson Decides Not to Cross White Oak Swamp

Wing/Corps-Level Tactical Decision

Jackson’s command was a direct pressure force that was to maintain close contact with the retreating Union army and to attack and attempt to slow down the retreat whenever the opportunity presented itself. Jackson’s planned route after crossing the Chickahominy was south across White Oak Swamp, then on to Glendale, and eventually to Malvern Hill. When Jackson reached White Oak Swamp, however, he found his way barred by a Union force on the other (south) side. Rather than choose to aggressively maneuver and attack, he allowed his command to sit mostly idle on the northern edge of the swamp.

Jackson’s decision kept three divisions (D.H. Hill’s, Whiting’s, and Winder’s) out of the Glendale battle, where they might have been enough for a Confederate victory. It also allowed some Union troops at White Oak Swamp to be sent as reinforcement to the Glendale fight. Jackson’s decision nullified a major portion of Lee’s plan and contributed to the Union army’s survival at Glendale, followed by a repositioning to Malvern Hill.

12. Huger Decides Not to Attack

Division-Level Tactical Decision

Major General Benjamin Huger’s Division was to march down the Charles City Road and, in conjunction with Longstreet’s and A.P. Hill’s Divisions, attack the Union forces at the Glendale crossroads on June 30. That morning, Huger’s Division was three miles from the crossroads. A mile after it commenced marching, it entered a wooded area with felled trees blocking the road, an obstacle to artillery and wagons but infantry, with difficulty, could continue toward Glendale. Huger, seen at left, however, decided to cut a parallel road through the woods. Union troops continued chopping down trees on the established road as fast as the parallel road was cut. Huger’s Division did not arrive at Glendale in time to have any effect on the battle. Jackson’s and Huger’s decisions kept four badly needed divisions out at Glendale, contributing to a successful Union defense and a continued retreat to Malvern Hill.

13. Magruder Ordered to Support Holmes

Army-Level Tactical Decision

During the pursuit, Lee ordered Magruder to follow and be prepared to support Longstreet and A.P. Hill. On June 30, Lee received a report that Union wagons were crossing Malvern Hill and he ordered Maj. Gen Theophilus H. Holmes’ Division to move down the River Road and attack Union forces on Malvern Hill.

Holmes was unsuccessful in breaching the strong Union position, and Lee ordered Magruder’s Division, essentially the army’s only reserve, to stop following Longstreet and A.P. Hill and move south to support Holmes. Shortly thereafter, Longstreet and A.P. Hill commenced The Battle of Glendale. Several hours later, Magruder was ordered to reverse course and march to Glendale to support the attack.

By the time his troops got there, it was too late. Longstreet’s and A.P. Hill’s attacks almost penetrated the Union defense at several locations, but neither commander had sufficient force to take advantage of the situation. The commitment of Confederate reserves might have cut off a significant portion of the Army of the Potomac. Lee’s decision removed a division from his attack, and together with Jackson’s and Huger’s forces, prevented five divisions with 17 infantry brigades and 23 batteries from getting into action. Union troops continued their march to Malvern Hill.

14. Lee Orders an Attack

Army-Level Tactical Decision

On July 1, the Army of the Potomac had formed a formidable artillery and infantry defensive position on Malvern Hill. In the morning and early afternoon, Confederate divisions began to move within striking distance of the Union defenses. When Union artillery suppressed the crossfire of Confederate artillery, it appeared that no infantry attack would take place.

Lee, however, received incorrect information that Union artillery and infantry were withdrawing and ordered his infantry to attack, resulting in multiple unsuccessful brigade attacks with a high number of casualties, and a Union victory. Malvern Hill was Lee’s last chance to damage the Union army.

This battle, with 5,650 Confederate casualties, was the second bloodiest of the Seven Days. With the other battles during the campaign, Lee’s army had suffered 20,204 casualties, 22 percent of its strength. After Malvern Hill, Lee ceased combat operations and begin to consolidate, reorganize, and resupply his army.

15. McClellan Retreats, Again

Army-Level Tactical Decision

McClellan won a resounding defensive victory on July 1 and had the opportunity to hold his strong position or to counterattack. He chose to do neither. On the night of July 1, Union troops abandoned the Malvern Hill position and continued their retreat. On July 2-3, McClellan’s army marched seven miles on the River Road to Berkley Plantation and Harrison’s Landing. With this critical decision, McClellan gave up any tactical advantages he had gained on July 1 and essentially brought the Seven Days Campaign to a close.

16. Halleck Decides to Evacuate the Peninsula

National-Level Strategic Decision

The Army of the Potomac occupied positions at Berkley Plantation and Harrison’s Landing from July 3 into August, staying secure behind defenses and resupplying. No offensive operations were conducted. Lincoln and then the new general-in-chief, Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck, both visited McClellan to discuss several proposed offensive options, among them renewed operation on the north side of the James against Richmond or on the southside against Petersburg. McClellan, however, demanded more troops and remained in place. Halleck then ordered the Army of the Potomac to march to Fort Monroe and then be sent back to Alexandria and Washington by ship. This decision ended combat operations on the Peninsula. Union troops would not be this close to Richmond again until the late summer of 1864.

Matt Spruill is a retired U.S. Army colonel and author of 10 Civil War books, who now resides and writes from Colorado. The critical decisions he summarizes in this article can be fully explored in his new book, Decisions of the Seven Days: The Sixteen Critical Decisions That Define the Battles, published as part of the University of Tennessee Press’ newest series “Command Decisions

in America’s Civil War.”