[shopping_cart_button text=”A View From Abroad: The Story of John and Abigail Adams in Europe” price=”Buy Now” url=”https://www.amazon.com/gp/product/1479802875?ie=UTF8&linkCode=ll1&tag=historynet02-20&linkId=df380e47dd7b2c571cf2706cda409959&language=en_US&ref_=as_li_ss_tl”]

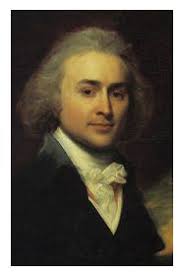

John Adams is not America’s most popular Founding Father. Historian Gordon S. Wood cast him as “the representative of a crusty conservatism that emphasized the inequality and vice-ridden nature of American society.” In her history of the American Revolution, Mercy Otis Warren blamed that on her contemporary’s time in Europe. On the Continent, Warren charged, Adams “abandoned his earlier revolutionary principles under the corrupting influence of the French and English royal court.” Not so, argues University of Denver historian Jeanne E. Abrams in her new study.

Sent to France on a 1778 diplomatic mission amid the Revolution, Adams, save for occasional expeditions home, wound up spending nearly a decade in Europe before relocating permanently in the United States in 1788. He set forth with a head full of ideas about human nature and government derived from reading deeply in “law, history, theology, political philosophy, and literature.” All that book learning acquired real-world context from stays in Paris, Amsterdam, and London, as well as extensive travel around Europe. His demi-expatriate experience exerted penetrating impact on Adams’s understanding of America, its people, and government in general.

Abrams tracks Adams as he pursues much-needed wartime and then peacetime financial aid in Holland and France. He helps out on the 1783 Peace of Paris, securing American independence; negotiates with the Barbary States for release of captured American sailors; and serves as the new nation’s first minister to Great Britain. Unpacking the Adamses’ residency in Europe, A View from Abroad interweaves political and diplomatic history with quotidian activities. Incorporating Abigail’s European experiences—she joined John in 1784—deepens the portrait. So does integrating the four Adams children. Daughter “Nabby” and son John Quincy came of age in Europe, as shown by portraits painted in England by Mather Brown (Nabby) and John Singleton Copley (John Quincy).

Abrams vividly describes the family’s harrowing ocean crossings and often-miserable landward slogs. Traversing northern Spain’s Pyrenees, an exhausted Adams remarked in 1780, “journeying and voyaging…I have often undergone severe Tryals and great Hardships, cold, wet, heat, fatigue, bad rest, want of sleep, bad nourishment, &c., &c., &c. But I never experienced any Thing like this Journey.” The narrative tours the Adams residence at Auteuil, a Parisian suburb, and their house in London’s fashionable Grosvenor Square, where Abigail enjoyed what Virginia Woolf would someday endorse. “I always had a fancy for a closet [study] with a window which I could more peculiarly call my own,” she wrote to John in 1776.

The Adamses were prolific correspondents. Abrams taps letters between family members and voluminous exchanges with friends and relations, such as Abigail’s sundry letters to sisters Mary Cranch and Elizabeth Shaw. Abrams introduces many with whom they mixed: At Versailles, France’s King Louis XVI; Queen Marie-Antoinette, “an object to[o] sublime and beautiful for my dull pen to describe,” the besotted John recorded; and the Comte de Vergennes, a French minister who “locked horns” with Adams. In England, they met King George III—he and John “shared a common affinity for farming and a love of books”—and Queen Charlotte, “rather dull,” recorded Abigail. Among American confrères was the much-feted Benjamin Franklin, in many ways John Adams’s opposite; Thomas Jefferson, “one of the choice ones of earth,” Abigail submitted; and Philadelphia’s Anne Bingham, a socialite wherever she went. The Adamses also encountered Europe’s underbelly; the Continent’s glaring social and economic inequalities appalled them.

Abrams grants her protagonists their inconsistencies. The Adamses may have disparaged fellow citizens for consuming “fripperies” and “gew-Gaws and triffels,” but that pecksniff pose did not stop John from sending home to Abigail—before she joined him—stores of “fine handkerchiefs, gauze fabric, ribbons, decorative feathers, and artificial flowers, as well as intricate lace from Holland,” all of which “successful businesswoman” Abigail hawked in Puritan Massachusetts. In Europe, the Adamses did not always practice American-style frugality but struggled to walk a “fine line between extravagant luxury and a level of materialism that reflected refinement.” Still, unlike the “financially challenged” Jefferson, the Adamses managed “to live within their means.” As Abrams notes, “Balance and moderation were always key aspirations for Abigail and John in their personal lives as well as their views on American governance.”

The Adamses’ workaday version of the Grand Tour “broadened the worldviews of both John and Abigail” and “made them even more American in outlook.” In the end, John Adams’s “perch in Europe” magnified his “deep-seated fear of an American aristocracy,” as evidenced by his A Defense of the Constitutions of Government of the United States of America. Bewildering to 18th-century Americans, that tome has not enhanced Adams’s long-term popularity. But, as he wrote to Mercy Otis Warren’s husband, James, “Popularity was never my mistress, nor was I ever, or shall I ever be a popular man.” —Mark G. Spencer is professor of history at Brock University in St. Catharines, Ontario.