How a rainstorm and a navigational error led to the murder of two U.S. Army aviators in Mexico.

More than a month had passed since U.S. Army Air Service Lieutenants Cecil Connolly and Frederick Waterhouse took off from Calexico, Calif., bound for Rockwell Field, San Diego, and vanished during a patrol flight along the U.S.–Mexico border.

The mystery surrounding their disappearance captured national attention as fellow Army airmen flew thousands of miles in a fruitless search for them and their Liberty DH-4B.

On September 21, 1919, the crew and passengers of the steamship Navari, traveling south from the Colorado River through the Gulf of California to Santa Rosalía, found themselves in need of fresh water. Captain Alejandro Abaro turned the 50-foot boat toward shore at Bahía de los Ángeles and dropped anchor. One of the passengers, Joseph Richards, a railroad worker from Chicago, waded ashore carrying an empty water keg. Having filled his keg at a natural spring 200 yards inland, Richards returned to the beach, where Navari rolled gently in the swells.

“I was the first man back to the boat,” said Richards. “So, when I got back I began walking the beach looking for sea shells. I smelled an awful strong odor. I seen [sic] a mound of dirt sticking up. I went over there and I seen [sic] a human skull in the sand. I dug the skull up [and] then I took part of a turtle shell and dug in the sand and hit against a boot. I got hold of the boot and pulled on it [and] pulled him clean out of the sand.” Richards examined the body and found it dressed in an Army uniform with high-laced boots and gold buttons embossed with wings and a propeller.

“I went and got a shovel from the boat,” continued Richards. He proceeded to dig and uncovered a second body six inches below the sand next to the first. He noted that the second body “Had on a pair of oxblood shoes and leather leggings.” In a pocket was a lieutenant’s bar.

Richards had discovered the mortal remains of Connolly and Waterhouse. Within weeks the story of their disappearance, the ordeal of their brief survival—a diary scratched into the fuselage of their airplane—and the facts surrounding their senseless murder would be revealed to the world.

Sadly, 100 years later, more is known about the airmen’s deaths than about their short lives and military service. Their records were among those destroyed in the disastrous fire at the National Personnel Records Center near St. Louis, Mo., in 1973.

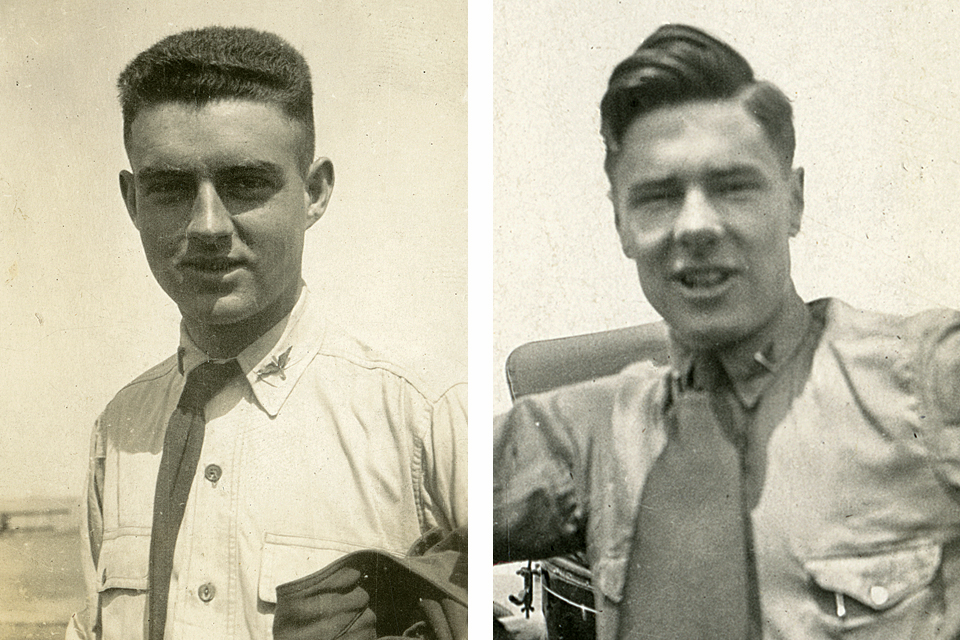

Frederick B. Waterhouse was born on October 1, 1896, in Weiser, Idaho, just a stone’s throw across the Snake River from Oregon. At some point he joined or was drafted into the Army, and in early 1917 was a private at the Signal Corps Aviation School at Rockwell Field. After completing flight training and being commissioned a second lieutenant, Waterhouse joined the 36th Aero Squadron at Kelly Field in San Antonio, Texas, while it trained for deployment to France. On September 19, 1917, the 36th joined the American Expeditionary Forces in France, where advanced training continued at the AEF base at Issoudun. It’s unknown if Waterhouse deployed with the squadron, and the war ended before it ever saw combat. He was transferred back to Rockwell Field in December 1918.

Born in Oklahoma on November 8, 1897, Cecil W. Connolly was an Army brat whose father was a career military musician. Like Waterhouse, Connolly joined or was drafted into the Army and trained as a pilot, earning his commission as a second lieutenant on April 3, 1918. Records for the following months show Connolly in Texas at Camp Dick in Dallas and at Camp Call in Wichita Falls for “Duty requiring regular and frequent aerial flights.” In October 1918 he was sent to New York to attend radio operators’ school at Columbia University, and was likely there when World War I ended on November 11, 1918. He was stationed at Penn Field near Austin in February 1919, and the following month joined Waterhouse and other aviators as members of the 9th Corps Observation Squadron at Rockwell Field under the command of Major Henry “Hap” Arnold, future general of both the Army and the Air Force. Their mission was to patrol the U.S. border with Mexico.

Mexico had been wracked by violence and revolution since at least 1910, and the U.S. had initiated aerial patrols along the border in 1913. Raids into the U.S. by Mexican revolutionary Pancho Villa and weapons and ammunition illegally flowing south created a national resolve to increase those patrols when WWI ended.

The airmen flew war surplus DH-4s and Curtiss JN-4s. Radios, if installed, could only transmit code; compasses were unreliable; maps were sketchy and of little use; and the border country was bleak, rugged and sparsely populated.

On August 16, 1919, Waterhouse and Connolly departed Rockwell Field at about 9 a.m. in their compass-equipped DH-4, accompanied by a second DH-4, and headed east, arriving in Yuma that afternoon. Rain showers, fouled plugs and loose fabric delayed their return trip for two days. Departing for San Diego on the 18th, they made it as far as Calexico before the plugs again fouled, forcing them to land in a field, which damaged both wheels. A mechanic and two wheels were dispatched from Rockwell by automobile, and two days later the pair again departed for San Diego…and disappeared. A witness later reported seeing an airplane enter a rainstorm near Jacumba, Calif., and emerge flying roughly southeast.

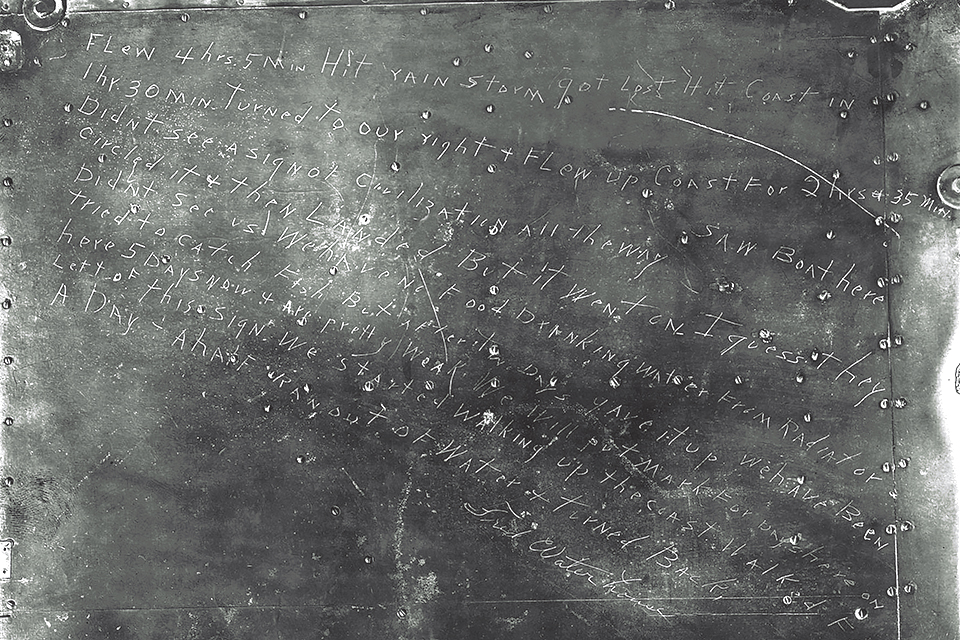

Upon entering the storm it is evident the westbound aviators slowly and inadvertently turned southeast. After exiting the rain they either chose to not believe their compass or the instrument had already failed. Among the messages the pair would later scrawl into the fuselage of their aircraft was one by Waterhouse stating: “Hit rain storm got lost. Hit coast in 1 hr. 30 min. Turned to our right [and] flew up coast for 2 hrs. 35 min. Didn’t see a sign of civilization all the way.”

Based upon the DH-4’s cruising speed of 90-95 mph, this makes sense. Calexico to Jacumba is 40 miles and would have taken approximately 25 minutes. The distance from Jacumba to the Gulf of California coast on a southeasterly heading is approximately 110 miles, or an additional 1 hour, 9 minutes. From there the message clearly indicates the pair believed they were flying north along the California coast. They apparently missed the fact that Jacumba to the California coast was only 55 miles, which they should have reached in just 35 minutes had they been flying west.

As Connolly and Waterhouse flew on, the enormity of their predicament must have gnawed at them. After following what they believed was the California coastline for more than 2½ hours, their fuel nearly exhausted, they may have thought their luck had suddenly changed. “Saw boat here circled it [and] then landed,” wrote Waterhouse. “But it went on I guess they didn’t see us.” The pair had successfully landed their DH-4 on a deserted stretch of white-sand beach about 20 miles north of the coastal settlement of Bahía de los Ángeles.

With the aviators now overdue and missing, rumors and reports suggested that the pair had likely flown into Mexico. In his history of Rockwell Field, Hap Arnold stated that air patrols were immediately launched, in addition to ground expeditions with the cooperation of Mexican authorities. “The country was systematically and thoroughly searched from the air and on the ground for a distance of approximately 120 miles south of the border,” Arnold wrote. Indeed, a map drawn of the search by air and land covered thousands of miles and came tantalizingly close—within 20 miles—of the stranded aviators.

Meanwhile, at Connolly and Waterhouse’s encampment, conditions were bleak: “We have no food. Drinking water from radiator. Tried to catch fish but after two days gave it up. We have been here 5 days now [and] are pretty weak.” Not content to wait and by now keenly aware of their error, the pair decided to try to walk to help. “We started walking up the coast. Walked for a day [and] a half. Ran out of water [and] turned back.”

The search was proving a challenge. On August 26, it was temporarily called off based on a rumor that the pair had been found by Mexican soldiers, but then resumed when the rumors turned out to be false. On September 11, with no solid leads, the War Department called off the search.

On October 13 the men at Rockwell Field finally learned the fate of the two aviators when word from Joseph Richards reached them via the U.S. Consulate at Nogales. Three days later an expedition aboard the destroyer Aaron Ward sailed for Angeles Bay and found the bodies of Connolly and Waterhouse as described. Their remains were carefully placed into flag-draped caskets on Aaron Ward’s deck.

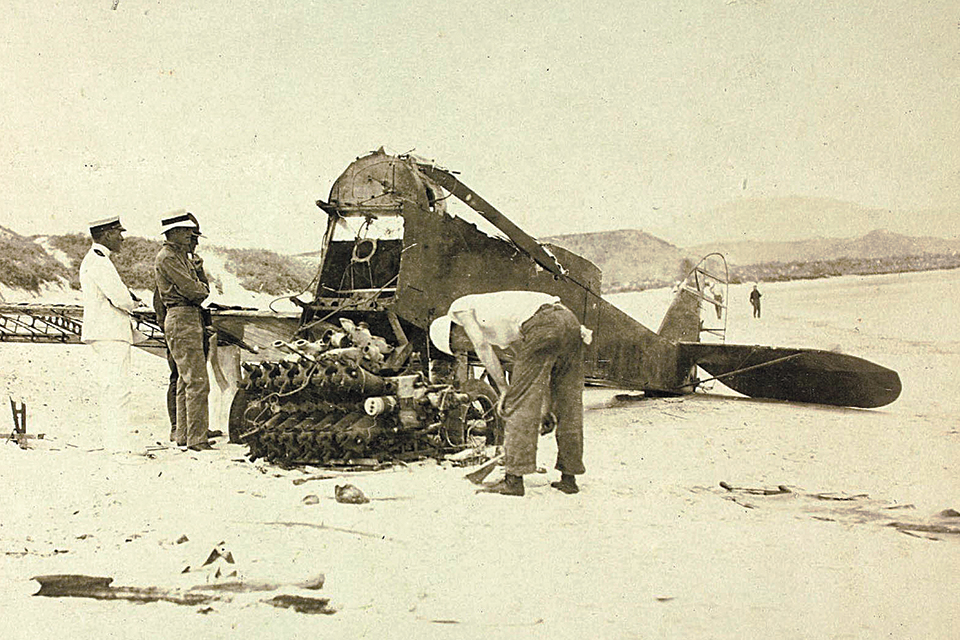

Twenty miles north, the partially disassembled DH-4 was discovered where the airmen had landed. Locals had begun to cannibalize the aircraft for useful parts. Its remains were set ablaze after the panels into which the pilots had scratched the record of their ordeal were carefully removed. One entry read, “We will put mark for days here on left of this sign.” Seventeen hash marks bore silent witness to the tragedy that had unfolded there, along with messages from both men to

their mothers:

“Dearest Mother, We have been here now 10 days. No signs of any help [and] our water nearly gone so I thought I would write a short letter to you while I had the strength. I don’t want you to grieve for me. I want you to have everything which is not much. All my love to you + sis + dad. Your loving son, F.B. Waterhouse”

And from Connolly, “My time to die is here. God knows [it] will be welcome enough after our suffering so for 11 days of hunger. Try to forget my fate. What I have is yours. Use it for your comfort and happiness. I tried to live a good life and I do not fear death. I have slighted you in ways I am sorry for now. But can’t make it right this late. Please do not wear mourning for me. Love to you, Dad, Nora Hazel and Ethel. God bless you all. Cecil”

According to the investigation that followed, the aviators were found in a weakened and emaciated state by two fishermen, Calixto Ruiz and Santiago Fuerte, on or around September 6 and taken the 20 miles to Bahía de los Ángeles. There, within days, Ruiz and Fuerte murdered the airmen for the little money in their pockets and crudely buried them. Claiming self-defense—allegedly during a fight—in their Mexican court trial, the perpetrators eventually served only five years for their crimes.

Connolly’s and Waterhouse’s parents met Aaron Ward when it docked in San Diego on the afternoon of October 26. Both men were accorded full military honors as their caskets were carried onto the pier.

Second Lieutenant Cecil Connolly, age 21, is buried at the Fort Rosecrans National Cemetery in San Diego. Second Lieutenant Frederick Waterhouse, age 22, is buried in his hometown of Weiser at Hillcrest Cemetery.

In light of the career of their commander, Hap Arnold, there’s no telling to what heights these two young airmen might have risen had a cruel fate not intervened.

U.S. Air Force veteran Craig Thorson writes from Fort Worth, Texas. He is a Boeing 777 captain with 45 years’ aviation experience and loves researching little-known aviation history. Recommended for further reading: The History of Rockwell Field to 1924, by H.H. “Hap” Arnold.

This feature originally appeared in the March 2019 issue of Aviation History. Subscribe here!