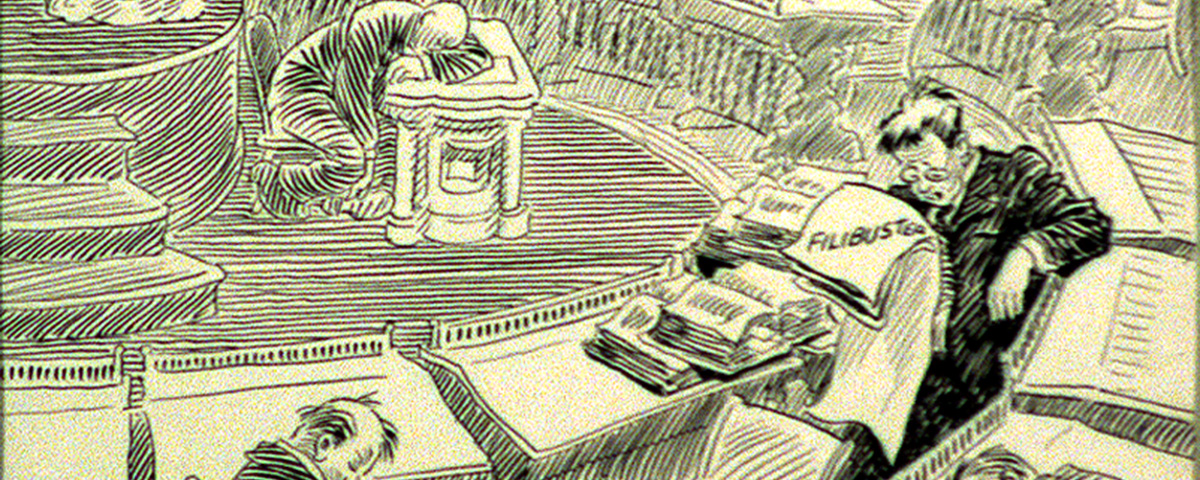

Filibusters tend to be more infuriating than inspirational.

After talking non-stop for 10 hours and 35 minutes, Huey Long informed his fellow senators that he wasn’t a bit tired. “I would just as soon stay here and go ten more hours,” he said. “I am in hog heaven here discussing this thing.”

It was 10:30 on the night of June 12, 1935, and Sen. Long had been yakking since noon, trying to prevent a vote that he knew he would lose. The Senate was prepared to pass an extension of President Franklin Roosevelt’s National Recovery Act, which Long opposed, and he was trying to talk the bill to death. Huey was a very entertaining talker, so spectators packed the gallery, many of them Shriners in town for a convention. “I seem to have new inspiration,” Long announced. “I seem to hear a voice that says, ‘Speak ten hours more.’”

During his epic filibuster, Long mostly ignored the National Recovery Act, preferring to read from the Constitution, quote the Bible and tell funny stories about his drunken uncle and the snakes of his native Louisiana. He jokingly proposed a bill to repeal “every law that has been enacted by the Hoover and Roosevelt administrations.” He gave a step-by-step lesson in how to fry oysters, and then he picked up a wastebasket and demonstrated how to make potlikker. “If you had a pot of turnip greens about two-thirds the size of this wastebasket,” he said, “you ought to put in about a 1-pound hunk of side meat that is sliced, but not clear through, just down to the skin part…”

As the night dragged on, Long periodically praised his own oration, describing it as “this masterful speech” and “a marvelous speech” and “one of the greatest speeches that has ever been made in this body.” After filibustering for 15 hours, he even had the audacity to proclaim, “I do not believe in filibustering.” Then he came up against the powerful force that dooms most solo filibusters—the call of nature. At 3:50 a.m., his bladder bursting, Long yielded the floor and dashed to the men’s room. The Senate soon passed the bill.

Long’s marathon monologue inspired actor Jimmy Stewart’s famous filibuster scene in Frank Capra’s classic 1939 movie Mr. Smith Goes to Washington. And the movie helped create the enduring notion of a filibustering senator as a lone hero courageously defying the corrupt political establishment. It’s a heart-warming image but, alas, it’s a myth. Most filibusters are neither solo nor courageous, and they tend to be more infuriating than inspirational.

The colorful history of filibusters is a smorgasbord of idealism, cynicism, egomania, buffoonery and, if truth be told, a great deal of blatant racism. And it involves much more than just talking a bill to death. “A filibuster is any device used by a minority to prevent a vote because presumably the majority would win,” says Donald A. Ritchie, the Senate’s official historian. Indeed, these days the mere threat of a filibuster is enough to create gridlock.

Filibusters tied up the ancient Roman Senate, as well as the British Parliament. Wherever you find legislatures, you’ll find legislators stalling to prevent votes they know they’ll lose. But stalling is part of the very fabric of the U.S. Senate. The Founding Fathers created the Senate as a check on the House of Representatives, which was closer to the people and would therefore, the Founders believed, be inflamed by the wild passions and whims of the rabble.

In the early republic, filibusters tied up both chambers of Congress, but in 1811 the House enacted rules to limit debate. The Senate, a smaller body composed of larger egos, defeated all attempts to restrict debate for another 106 years. Consequently, the Senate frequently found itself handcuffed by a small minority—or by one long-winded member.

In 1841, when the Senate’s Whig majority wanted to fire the official Senate printers, the Democratic minority filibustered for a week, and the debate devolved into personal attacks so malicious that Democrat William King of Alabama challenged Whig leader Henry Clay to a duel. Clay accepted the challenge, and the two men might have killed each other if they hadn’t been hauled before a magistrate, who put the kibosh on the shootout. A few months later, Democrats filibustered for weeks against a Whig bank bill. Irate, Clay announced that he would sponsor legislation permitting a Senate majority to cut off debate, but he was forced to back down when his fellow Whigs told him they’d vote against it.

In 1846 Southern senators filibustered against a bill to appropriate money to purchase land from Mexico because it contained an amendment that prohibited slavery in the purchased territory. After a month-long filibuster, the appropriation passed—but without the antislavery provision.

Filibusters became increasingly common in the decades after the Civil War, with loquacious senators trying to kill bills on issues ranging from federal silver purchases to black voting rights. In 1903 Benjamin “Pitchfork Ben” Tillman, a South Carolina Democrat, threatened to filibuster all pending legislation unless the Senate paid his state $47,000 that he claimed it was owed for expenditures in—believe it or not—the War of 1812. When the Senate capitulated and approved the appropriation, Rep. Joseph Cannon rose on the floor of the House and demanded that the Senate “change its methods of procedure.” If not, he threatened, the House “backed up by the people, will compel that change.” Cannon’s House colleagues cheered his speech but the Senate, in its lofty majesty, ignored it. It takes more than insults from the House to change Senate rules. In this case, it took World War I.

.jpg)

In March 1917—shortly before the United States entered the war—President Woodrow Wilson urged Congress to pass a bill to arm American merchant ships against German submarines. A dozen antiwar senators, led by Wisconsin progressive Robert LaFollette, filibustered the bill and defeated it. Wilson denounced this “little group of willful men” and demanded that the Senate curb filibusters. In the wartime patriotic frenzy, the Senate complied, passing Rule 22, which allowed it to end debate on a bill if two-thirds of senators vote for “cloture.”

The cloture rule provided a method for cutting off filibusters by a small group, but it was powerless against filibusters supported by more than a third of senators, which explains how Southern Democrats were able to use filibusters to kill every meaningful civil rights bill for the next 47 years.

The Southern filibusters were serious, well-organized power plays designed to defeat any attempt to extend equal rights to black people. For decades, the House passed bills to outlaw discrimination and protect the right of black citizens to vote, only to watch the bills killed by filibusters in the Senate. In an era when white mobs frequently lynched black people with impunity, Southern senators used filibusters to defeat anti-lynching bills in 1922, 1935, 1938, 1948 and 1949.

While filibustering to deny rights to minority groups, Southern senators had the gall to tout the filibuster as a tool to protect minority rights—meaning the right of a minority of senators to prevent the majority from voting on civil rights bills.

“Without the filibuster,” said Sen. Theodore Bilbo of Mississippi, “the minority would be at the mercy of the majority.”

“The filibuster is the last defense of reason, the sole defense of minorities,” said Sen. Lyndon Johnson of Texas, while filibustering against a 1949 civil rights bill.

Sen. Millard Tydings of Maryland took the argument even further: “It was cloture,” he said, “that crucified Christ on the cross.”

Not surprisingly, the longest solo filibuster in history was an anti–civil rights monologue. It came in 1957, when Lyndon Johnson was the Senate majority leader. Johnson wanted to become president but he calculated that he could never win the Democratic nomination if he was associated with the Senate’s infamous filibusters. So he carefully crafted a civil rights bill so toothless that his Southern colleagues agreed not to filibuster against it. But one senator broke that agreement—Strom Thurmond of South Carolina, who was worried about reelection.

On August 28, 1957, Thurmond took a steam bath to dehydrate his body so it could absorb liquids without requiring a bathroom break. Armed with malt tablets and bits of cooked hamburger and diced pumpernickel, he began talking at 8:54 p.m., and he didn’t stop for the next 24 hours and 18 minutes. He read the voting laws of all 48 states and quoted George Washington’s Farewell Address, but he forgot to mention that 35 years earlier he had impregnated his parents’ 16-year-old black maid, and consequently one of the people he was fighting to keep segregated was his daughter.

Thurmond’s marathon broke the filibuster record set by Sen. Wayne Morse in 1953, when the Oregon maverick denounced an oil bill for 22 hours and 26 minutes. “I salute him,” Morse said of Thurmond. “It takes a lot out of a man to talk so long.”

But Thurmond’s Southern colleagues didn’t salute. They were livid when Strom’s publicity stunt sparked a barrage of phone calls and telegrams from angry segregationists back home, who demanded to know why they weren’t helping Thurmond fight for white supremacy.

“If I had undertaken a filibuster for personal political aggrandizement,” said Richard Russell of Georgia, the leader of the Southern caucus, “I would have forever reproached myself for being guilty of a form of treason against the South.”

Seven years later, in 1964, President Johnson committed his own “treason against the South” by supporting a strong civil rights bill. Again, Southern senators tried to kill the bill by filibuster, but times had changed. American television viewers had watched Southern cops attacking nonviolent black protestors with nightsticks, dogs and fire hoses, and civil rights had become the moral issue of the age.

On March 30, as the Southerners started filibustering, CBS News reporter Roger Mudd began filing bulletins from the steps of the Capitol several times a day, standing next to a clock that ticked off the days and hours of the filibuster. The clock reached day 57—June 10—when Sen. Robert Byrd of West Virginia finished his 14-hour anti–civil rights speech, and then the Senate finally voted on a cloture motion. The motion required 67 votes—two-thirds of the Senate—and everyone knew it would be close.

A Senate clerk called the roll. “Mr. Aiken.”

“Aye.”

“Mr. Ellender.”

“No.”

“Mr. Engle.”

Two navy corpsmen wheeled Sen. Clair Engle, a California Democrat, down the center aisle. Engle was dying of brain cancer and his voice was too weak to be heard. Slowly, painfully, he lifted his hand and pointed to his eye.

“Mr. Engle votes ‘aye,’” said the clerk.

The “ayes” won. For the first time in history, the Senate voted to break a filibuster on a civil rights bill. Nine days later, the Senate passed the landmark law that ended segregation.

The filibuster was tainted by its connection to Southern racism, but after 1964, it became just another legislative tactic, used by all kinds of senators for all kinds of reasons. For starters, in 1968 a bipartisan filibuster defeated President Lyndon Johnson’s nomination of Abe Fortas as chief justice of the Supreme Court.

In 1975 the Senate changed the number of votes needed for cloture from 67 to 60. Two years later, a pair of senators opposed to a natural gas deregulation bill tried to kill it with a “post-cloture filibuster”—bringing up scores of amendments and demanding time-consuming roll call votes on each. After 13 days of mind-numbing tedium, Robert Byrd, who was then Senate majority leader, thwarted the filibuster with a complex parliamentary maneuver, and the bill passed.

In 1987 Republicans defeated seven cloture votes to kill a Democratic campaign finance reform bill. When Democrats brought up the bill again in 1988, Republicans launched another filibuster. “We are ready to go all night,” said Republican Whip Alan Simpson of Wyoming. “We will have our sturdy SWAT teams and people on vitamin pills and colostomy bags and Lord knows what else.”

During the long night, Republican senators boycotted a roll call vote and in their absence, Democrats voted to command the Senate sergeant-at-arms to “arrest the absent Senators and bring them to the Chamber.” Sergeant-at-Arms Henry Giugni found Republican Robert Packwood of Oregon in his office and arrested him. Packwood insisted that he be carried into the Senate chamber—and at 1:17 a.m., he was. Despite the theatrics, the Republicans still killed the bill. “The events of the last 48 hours,” noted Republican Warren Rudman of New Hampshire, “were a curious blend of ‘Dallas,’ ‘Dynasty,’ ‘The Last Buccaneer’ and Friday Night Fights.”

That filibuster was a team effort; others were solo performances. In 1981 William Proxmire, a Wisconsin Democrat, spoke for 16 hours and 12 minutes to protest the fact that the national debt had reached a trillion dollars. (Now it’s over 12 trillion.) In 1986 Alphonse D’Amato, a New York Republican, spoke for 23 hours and 30 minutes to protest a defense bill that failed to fund a warplane made in his home state. In 1992 D’Amato spoke for 15 hours and 14 minutes against a bill that he claimed would hurt a New York typewriter company. (In both years, perhaps not coincidently, D’Amato faced tough reelection battles.)

The number of filibusters has soared since 1986, which might be connected to the fact that the Senate began televising its debates that year. Since then, senators from both parties have defeated judicial nominations by filibustering—or threatening to filibuster. This now occurs so often that it has become a ritual: When Democrats threaten to filibuster, Republicans demand “a simple up-or-down vote.” When Republicans threaten to filibuster, Democrats demand an up-or-down vote.

Whatever their party affiliation, critics of the filibuster are undeniably correct: The tactic is intrinsically undemocratic. But so is the Senate itself—a legislative body in which every state gets two votes whether it contains 550,000 people, like Wyoming, or 36 million, like California.

The Senate could end all filibusters by simply voting to amend its rules. Periodically, a senator proposes such a change, but the proposal inevitably fails because deep down, senators love the filibuster. They love it for two reasons. The high-minded reason was summed up by Sen. Byrd in 1989: “The framers of the Constitution thought of the Senate as the safeguard against hasty and unwise action by the House.” The less high-minded reason was summed up by Senate historian Donald Ritchie in 2010: “Asking a senator to speak for a long time isn’t a punishment. They love to do that.”

And so the filibuster goes on. And on. And on. Occasionally it gets downright bizarre. I witnessed one of those occasions on November 12, 2003, when I was covering the Senate for the Washington Post. Democrats were threatening to filibuster against four of George W. Bush’s judicial nominees. In response, Republicans concocted a wacky new tactic—the anti-filibuster filibuster. For more than 30 hours—all of one night and deep into the next—the Republicans filibustered to protest the Democrats’ plan to filibuster.

This anti-filibuster filibuster incensed Democrat Harry Reid of Nevada so much that he protested against it by—yes, you guessed it!—filibustering. He denounced the anti-filibuster filibuster for eight solid hours. Reid’s speech was the Senate’s first anti-anti-filibuster filibuster—and it included recipes for goulash, advice on how to keep rabbits out of the garden and a dramatic reading of six chapters of his book about his boyhood hometown of Searchlight.

It made for a long, absurd, surreal spectacle, and those of us who witnessed it will never forget it, no matter how hard we try.

Peter Carlson writes our Encounter column. His latest book is K Blows Top.