Mother Agnes Allison is remembered with an impressive zinc monument on a hilltop above Port Carbon, Pennsylvania

Port Carbon lies at the heart of eastern Pennsylvania’s anthracite coal region, on the banks of the Schuylkill River just east of Pottsville. First settled in 1826, it was a prosperous town of nearly 2,000 by the outbreak of the Civil War. Though primarily a coal town, it had a good number of sawmills and ironworks and was fed not only by the river but also rail lines and a canal. Before the war, plentiful work opportunities attracted hundreds of Western European immigrants to the area, and from 1861 to 1865 more than 500 Port Carbon residents—both foreign- and native-born—served in the Union Army.

In the summer of 1891, the Port Carbon Monumental Association was formed to raise money and determine the location for a memorial to those who served and especially to those who never returned home. The result of their efforts was an impressive zinc monument featuring a statue of a tall Union soldier atop a 22-foot-tall pedestal, inscribed with the names of some of the war’s bloodiest battles and relief portraits of Abraham Lincoln and Ulysses S. Grant.

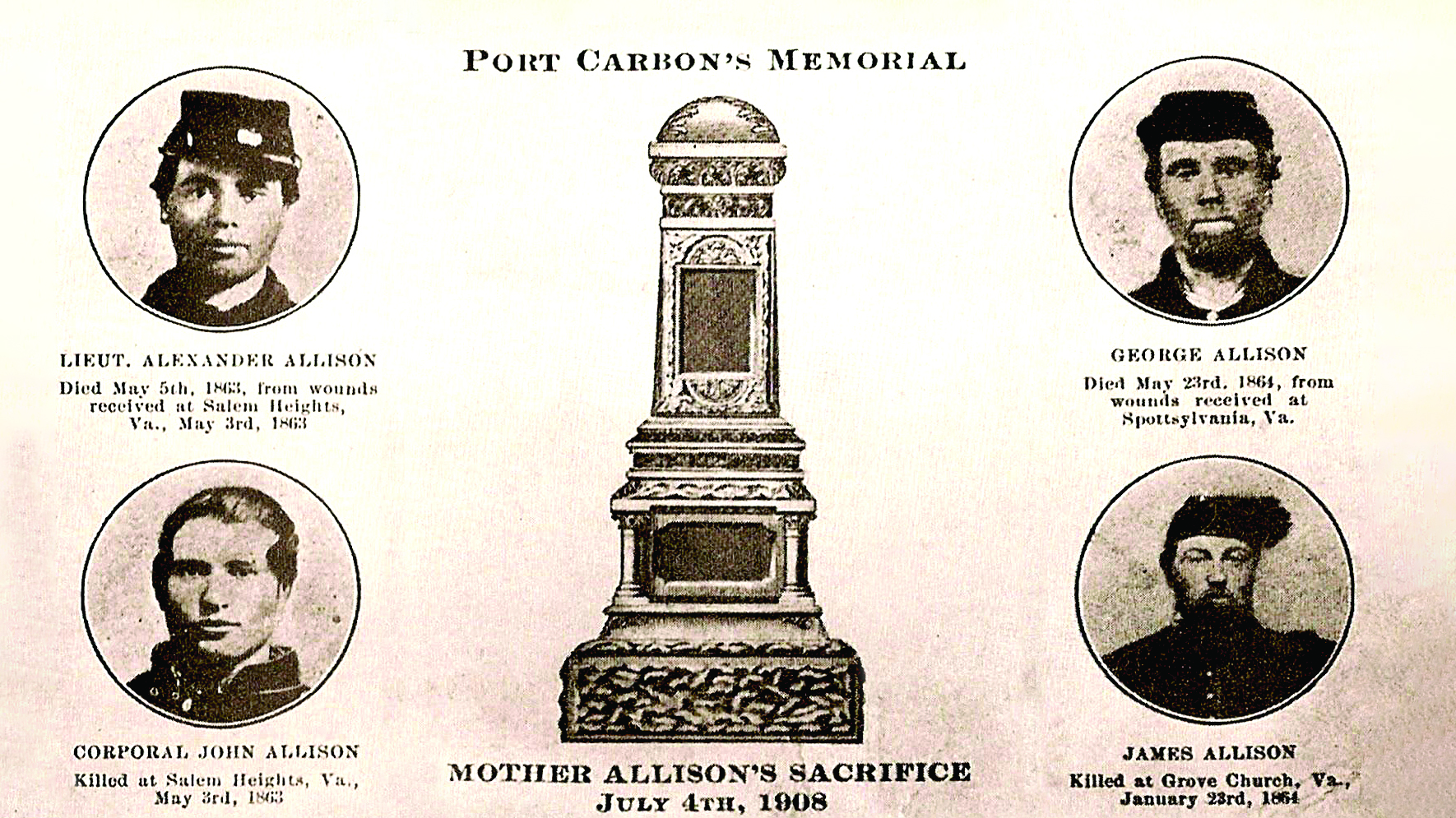

This impressive hilltop monument towers over Port Carbon. Yet it is not the town’s only Civil War memorial. The Port Carbon Monumental Association dedicated another one in 1908, much smaller but equally, if not more, poignant. Located in the Presbyterian Church Cemetery, it is known as the Mother Allison Memorial. It marks the grave of Agnes Allison, an immigrant from Scotland who passed away in 1887. The monument honors her memory but also pays tribute to her incredible sacrifice. During America’s bloodiest war, four of Agnes Allison’s sons marched off to war. All four would fall in battle.

Allison, born Agnes Smart in the early 1800s, married in about 1830 and would give birth to six sons over the next 12 or so years. The eldest three (David, George, and Andrew Jr.) were born in Scotland; however, the youngest (James, Alexander, and John) were born in Pennsylvania, meaning that sometime between the years of 1833 and 1836, the Allisons had immigrated to the United States, ultimately settling in Port Carbon. Agnes was widowed in 1845, left to raise her six sons alone.

In 1860, five of the sons still lived with her in Port Carbon. During the war, four would enlist in the ranks of three volunteer infantry regiments. Twenty-one-year-old Alexander, a blacksmith, and John—the youngest Allison boy at age 19—were mustered into the ranks of Company C, 96th Pennsylvania Infantry (John as a private, and Alexander as the company’s 1st sergeant). George, 25, enlisted as a private in Company K of the 56th Pennsylvania Infantry; James became a private in Company G of the 48th Pennsylvania Infantry. Agnes’ anxiety watching her boys march off to war must have been considerable, but it wouldn’t match the inconsolable grief she later felt as word arrived that each of her boys had perished in combat.

The first two to fall were Alexander and John, both struck down at Salem Church, Va., the same day: May 3, 1863. By then, the two had survived the carnage at Gaines’ Mill and Crampton’s Gap in the summer of 1862, two battles in which the 96th sustained particularly heavy casualties. Sergeant Alexander Allison was wounded at the latter battle but had recovered in time to rejoin the 96th, part of Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick’s 6th Corps, at the outset of the Spring 1863 Chancellorsville Campaign.

On May 1, 1863, Alexander was commissioned a 2nd lieutenant. Two days later, he led his men into a savage firefight at Salem Church on the outskirts of Fredericksburg. Emerging from a woodlot, the 96th Pennsylvania came under fire from Confederate Brig. Gen. Cadmus Wilcox’s Alabamians. Captain Jacob Haas of the 96th remembered seeing Allison repeatedly ordering his men to load and fire before being fatally wounded.

John, by then a corporal, was also struck down during the battle. Noted Haas, “It is not known whether John Allison was killed before Alexander was wounded. But during this heavy firefight with Minnie [sic] balls flying in every direction, John was dropped and instantly killed….”

The wounded Alexander was carried from the field and taken to a hospital at nearby Aquia Creek, where he died two days later. Alexander’s remains later were buried in the Fredericksburg National Cemetery under a marked headstone. It is likely that John was reinterred there as well, probably under an “Unknown” marker.

The Miners’ Journal, Schuylkill County’s main newspaper, mourned the slain brothers: “The death of Lieutenant Allison and his brother is deeply regretted. Their kind dispositions and fine soldiering qualities made them many warm friends who mourn their loss.”

Just more than a year later, on a battlefield scarcely 10 miles from where Alexander and John had fallen, Agnes would lose another son during the slaughter at Spotsylvania Court House. George, a 28-year-old private in Company K, 56th Pennsylvania whose battle honors included Antietam, Gettysburg, and the Wilderness, went down on May 12, 1864, during a forlorn assault up the open slopes of Laurel Hill on a position defended by Maj. Gen. Charles Field’s Division. Although casualties were understandably heavy in the front brigades, those farther back also suffered. Field acknowledged the Union attackers’ bravery, calling their effort a “determined” one but “repulsed with great slaughter.”

George was mortally wounded during the assault, eventually dying May 23 at Emory Hospital in Washington, D.C. His body was brought back to Port Carbon for interment. Agnes buried George in the town’s Presbyterian Church graveyard on June 3. Yet, even as she buried George, Agnes’ thoughts undoubtedly turned to James, her only son still in uniform. What she didn’t know then was that James had fallen the same day at Cold Harbor.

On May 12, the day George Allison was mortally wounded, James emerged unscathed from a savage fight on the other side of the Union line, in which the 48th Pennsylvania suffered 130 casualties. James’ death at Cold Harbor three weeks later came as one of the regiment’s 70 total casualties. His remains were eventually buried at the Richmond National Cemetery.

It is difficult to imagine Agnes Allison’s pain and anguish at losing four sons in only 13 months. For her sacrifice, she would receive a pension of $8 a month, which was later increased to $15 a month. She filed her claim following the deaths of her first two sons and noted in her petition that she was “poor and [in] indigent circumstances—and that she is possessing no property real or personal.” She was dependent, the petition said, upon the labor and the work of her sons.

Somehow, Agnes found the strength to carry on. Locally, the sacrifice she made was widely known; but it went unnoticed at the national level. There would be no letter from President Abraham Lincoln like the missive he reportedly wrote (most likely, his secretary John Hay authored it) to the widow Lydia Bixby of Massachusetts in 1864, after having been told erroneously that Bixby had lost all five of her sons in the war (apparently two of her sons had survived). Yet Agnes must have taken some consolation when her sons were honored after the war by Union veterans from Port Carbon, who named their local chapter of the Grand Army of the Republic after them. And, when she died, members of the Allison Brothers’ G.A.R. Post No. 144 took charge of her funeral arrangements.

Final peace came to Agnes Allison on April 3, 1887. News of her death appeared the next day in the Pottsville Republican, under the headline, “Death of an Estimable Lady.” She died of pneumonia at age “about 80 years.” Her obituary noted that she was the mother of four “valiant sons, who freely gave their lives for the land they loved so well.” Three days later, she was laid to rest “with ceremonies befitting the beautiful and touching example she has left, of a mother offering up on the altar of her country’s liberties, the lives of her noble sons.” The members of the Allison Brothers’ G.A.R. Post turned out for the funeral, as did a number of delegates from the nearby St. Clair Post and the Gowen Post of Pottsville. Six veterans of the 96th Pennsylvania—Alexander and John’s old regiment—served as pallbearers. A “touchingly eloquent and patriotic sermon” was delivered, one that spoke clearly to “the benefit to be derived by contemplating the heroic and self-sacrificing spirit” of the “nobly and unassuming” Agnes Allison. Following the sermon, Agnes was interred in a grave next to George.

On Independence Day 1908, thousands gathered around Agnes’ grave site in the Presbyterian Church Cemetery to witness the unveiling of the zinc alloy Mother Allison Memorial. The names of Agnes’ sons who died in the war are inscribed upon each of the monument’s four sides. A larger plaque on the front lists the dates of their deaths and the battles in which they fell (although the date for James’ death reads, by mistake, January 1864 instead of June 1864).

A native of Schuylkill County, Pa., John Hoptak is the author of several books, including The Battle of South Mountain and Dear Ma: The Civil War Letters of Curtis Clay Pollock, and works as a park ranger/educator with the National Park Service. This post, adapted for print, originally appeared on Hoptak’s blog “48thPennsylvania.blogspot.com.”

This story appeared in the July 2020 issue of America’s Civil War.