In the 2013 film The Eternal Zero, Japanese siblings ponder their late grandfather’s life—and his mysterious death.

IN THE BATTLE OF OKINAWA in spring 1945, 24 American soldiers, sailors, and Marines were awarded the Medal of Honor for valor above and beyond the call of duty. Thirteen of these were granted posthumously, in several cases because the recipient had flung himself on an enemy grenade to save his comrades. We recall these men as heroes.

Offshore, more than 2,000 Japanese men flung themselves against American warships in attacks that, whether they failed or succeeded, always ended in their deaths. These were pilots of the “Divine Wind Special Attack Force,” named for a typhoon—“a divine wind,” or kamikaze—that destroyed a Mongol invasion fleet bound for Japan in 1281. We recall these men as insane fanatics who committed suicide by plane crash.

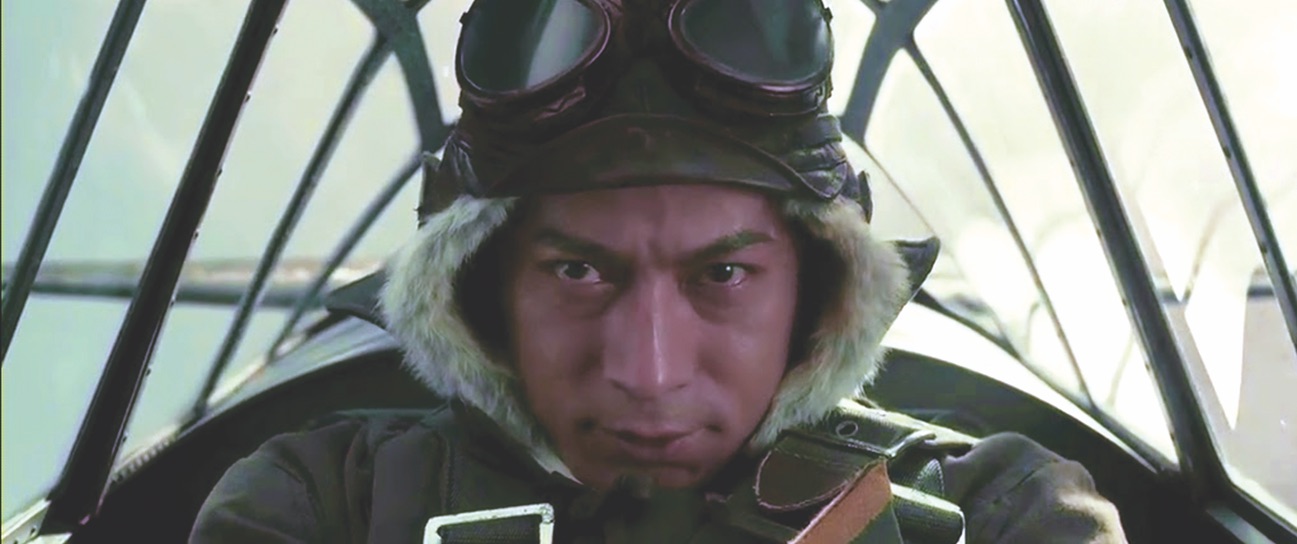

This paradox—praise for an impulsive sacrifice, scorn for a quite deliberate one—is explored in The Eternal Zero, a film that attracted huge audiences in Japan upon its 2013 release. Directed by Takashi Yamazaki, The Eternal Zero tells the story of Warrant Officer Kyuzo Miyabe (played by Junichi Okada in a performance that won him a Japan Academy Prize as Best Actor), who in the war’s closing days slammed his Zero fighter into the flight deck of an American aircraft carrier.

Miyabe’s story gradually emerges from a journey of discovery undertaken by two siblings, Kentaro and Keiko Saeki (Haruma Miura and Kazue Fukiishi), who learn after the 2004 funeral of their grandmother that the man they know as their grandfather is, in fact, her second husband; her first was Miyabe, their mother’s biological father. What little they know of him is this: he was a skilled pilot who inexplicably undertook a kamikaze mission. (Kamikaze pilots nearly always had only rudimentary training; skilled pilots were worth far more alive than dead.)

The mystery unfolds in a series of interviews with surviving elderly pilots, now in their eighties, who knew Miyabe during the war. Some snarl that Miyabe was the worst kind of coward. Others declare him a hero; still others portray him as a leader of rare compassion. I will not reveal the truth. Instead, I want to discuss a moment, midway through the film, when Kentaro Saeki joins a group of his friends at dinner. It’s a lighthearted occasion, and when Kentaro tells them of his search, it threatens to dampen the gaiety. “It’s not exactly our kind of conversation,” says one young woman. The others laugh.

A young man seated next to Kentaro is a study in condescension. If Kentaro wants to go in quest of his kamikaze forebear, then to each his own, he shrugs. “Goes to show suicide bombers aren’t a new thing.”

“Pardon me,” Kentaro says, “but don’t equate terrorists with kamikaze.”

“They’re the same. All brainwashed.”

“That’s not right,” Kentaro objects. “Kamikaze targeted aircraft carriers, powerful military weapons. Totally different from terrorists targeting innocent civilians.”

“You’re nitpicking details,” the man pursues. “I mean the basic concept of throwing your life away for an ideal.” From “a foreign perspective,” he lectures, “kamikaze and suicide bombers are the same. They were just nationalistic fanatics.”

A friend begs to differ; they weren’t fanatics, but rather romantics who “took pride in just wasting their lives for their country.”

Soon Kentaro has had enough. Leaping to his feet, he shouts, “You’re completely wrong!” Then he removes his wallet, slaps money on the table to cover his drink, and strides from the room with fierce resolve.

The analogy between kamikaze and suicide bomber is not merely the gaucherie of Kentaro’s friends. In 2009, a reporter for ABC News opined that “Japan’s infamous kamikaze…seem more related to the pilots of al-Qaeda than most Japanese today would like to admit. They were fanatically devoted to their emperor, who was considered a god at the time. They were motivated by self-righteous anger against the West.” After the coordinated terrorist attacks in Paris in November 2015, several French newspapers used the terms “kamikaze” and “suicide bomber” interchangeably.

It is strange that we in Western culture, operating from the “foreign perspective” invoked by Kentaro’s patronizing peer, could, by and large, fail to view kamikaze as warriors. We celebrate the 300 Spartans who held Thermopylae, knowing it meant certain death. We are awed by those soldiers and Marines who smothered hand grenades. We remember the Alamo. Why not the kamikaze?

“And how can man die better,” inquires Roman army officer Horatius in Thomas Babington Macaulay’s 1842 poetry volume Lays of Ancient Rome, “than facing fearful odds, for the ashes of his fathers, and the temples of his gods?”

Surely the pilots of the Divine Wind knew the answer to that. ✯

This article was published in the February 2021 issue of World War II.