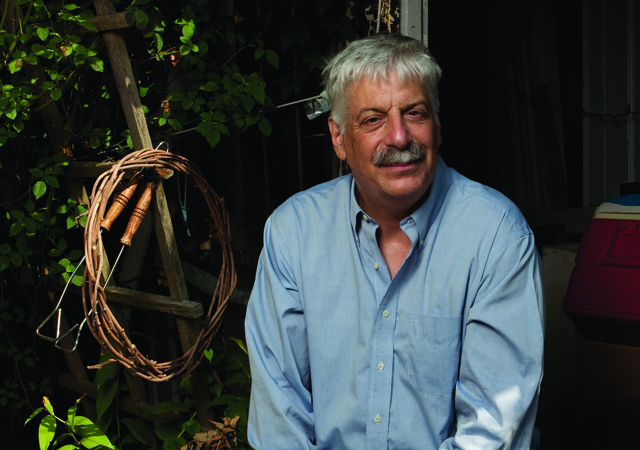

After Hurricane Katrina pounded New Orleans, many unwelcome things surfaced—including a lampshade made of human skin. Veteran journalist Mark Jacobson was enlisted to trace its story. In The Lampshade: A Holocaust Detective Story from Buchenwald to New Orleans, Jacobson, a contributing editor at New York magazine, recounts his remarkable two-year hunt. In the process, he raises revealing questions about what the Nazis did, how the Allies presented it, and why Holocaust deniers and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum play it down.

Did the Nazis make Jews into lampshades?

After the war, that was the truth, and everybody knew it. They’d seen lots of footage, photographs, headlines. Everybody thought it was horrible, evil, and that our civilization, with God on our side, had risen up to smite them. It let us feel good about ourselves. And it should.

Is there any evidence for this?

Eisenhower saw Nazi artifacts made from humans, including a lampshade, when he toured Buchenwald, and was legitimately horrified. That stuff was filmed. For him and others, the lampshade summed it up. Maybe, in retrospect, the Allies oversold it. But symbols are how the human mind thinks: The Holy Grail. The True Cross. Don’t give me a lot of details; give me something I can focus on. Symbols convince people to think in a certain way. The lampshade did that.

Were any Nazis found guilty of these atrocities?

Ilse Koch, “the Bitch of Buchenwald.” There was testimony at Nuremburg. Survivors said she had things made of Jewish people, especially their skin, and that she liked tattoos. When Lucius Clay, military governor of the American sector of Germany, commuted her sentence, there was an uproar. Ed Sullivan, Walter Winchell, all the big columnists screamed. In 1950 Congress was so outraged they convened a special committee about it. They’d demonized her to the point where she became as big as Hitler.

What changed?

Suddenly the Commies were our enemies and the Germans were our friends. So the demonizing shifted targets. Holocaust deniers say it was all propaganda. But that doesn’t mean it was untrue. The survivors of the camps kept the stories alive.

Where did that leave your lampshade?

Holding this icon of my postwar youth in my hand had a whole lotta resonance for me. So I had it DNA tested by the firm that worked on body parts from 9/11. Cost me five grand. It turned out to be real. Made of human skin. That’s why it was so hard to take when people said it was fake.

What people?

Start with the Holocaust Museum in D.C. My friend who found it was very determined we give it to a holocaust museum. Seemed like the thing to do. So I called them. No response. Finally I called their press rep and came on heavy. He presented me with Diane Saltzman, who was in charge of their collections then. She made it very clear she had zero time for this.

Why wasn’t she interested?

She insisted it was a myth, even though I’d sent the DNA report. I didn’t understand what she was talking about. Later, I began to understand. She said it was distracting. Sure, it’s sensationalist. In my opinion, she’s right—but only because they oversold the symbol to begin with.

How?

After the war, the human lampshade was central to the narrative of the Holocaust. It makes sense to try to put it back in perspective. You’ve got six million dead Jews and millions more dead people, no matter what Holocaust deniers say. We shouldn’t need a lampshade made out of human skin to know how evil that was. I understand that. Their point is, this stuff is so unusual it shouldn’t be part of the story. This symbol is no longer needed.

What’s wrong with that?

They want to narrow—and own—the narrative of the Holocaust. That’s dangerous. It gives the owners too much power. It shuts down asking questions. Raul Hilberg, the famous Holocaust historian, used to talk to Holocaust deniers. People thought that was horrible. He said, “Why not? They might say something interesting.” I’m with him.

Who else did you talk to?

Basically, I had this…thing, and I was trying to get somebody—anybody—to look at it. I started with Shiya Ribowsky, a cantor who was director of special projects at the medical examiner’s office in New York on 9/11. He took it out of the box—remember, he’d dealt with 20,000 body parts after 9/11—and said, “This is the saddest thing I’ve ever seen.” That was the first time I thought it might be real. Ken Kipperman is an individual obsessed with finding the Buchenwald lampshade. Michael Berenbaum is former project director at the U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum; he agreed with Saltzman that this stuff is distracting. Mike Smith, alias Denier Bud, said Jewish American propaganda officers planted the stuff at Buchenwald. Hans Ottomeyer, general director of the Deutsches Historisches Museum in Berlin, said, “There is an undue concentration on the darkness of German history.” Yehuda Bauer, a leading Holocaust scholar at Hebrew University of Jerusalem, encouraged me: “Keep telling the story. That’s what’s important. Write a book.”

Did you go to Yad Vashem [the official Israeli Holocaust Martyrs’ and Heroes’ Remembrance Authority in Jerusalem]?

Their two main curators and the head of the museum gave me an hour, basically to tell me they didn’t want to have anything to do with it. In Israel, they have a religious problem: they can’t have human remains. I could understand it; it was very fair. They didn’t question that it was human skin. But the DNA testing from this ancient, degraded skin meant I couldn’t prove its provenance—Buchenwald 1943, or even a Jewish person. The science isn’t available. That was their out. So I went to the Buchenwald Memorial.

What happened?

Volkhard Knigge, the director, took the lampshade for more testing. It turned out like the others. He e-mailed me, “There will be no last certitude about the object for now. That’s how history works.” But he agreed with Bauer: keep telling the story, keep asking questions.

How did the lampshade affect you?

When I began to realize the horror of the actual process of its creation, I almost screamed. A wave of sympathy overwhelmed me. The horror turned to sadness. The sadness turned to under- standing what the human species is capable of in a situation as crazy as the Third Reich. Skin defines us. Outward appearance. Racism. Tattoos. These are all connected. There’s no koan more untrue than “You can’t judge a book by its cover.” People are always doing that. Thinking like that made the lampshade more and more important to me. Why do some people think others are worth less than they are? I began having sympathy for this thing because I’m a human being. Was Ilse Koch a human being? Her son is born in prison, while she’s supposed to be in isolation. I have sympathy for him. I hope he’s figured a way to deal with the horrible existential situation he was born into. It wasn’t his fault.