John Elliott Cairnes’s devastating critique of Southern society sinks the Confederacy’s campaign to bond with Britain

In 1862, an Anglo-Irish political economist and abolitionist locked horns with Confederate lobbyists trying to formalize ties with Britain, the world’s leading industrial power. The United Kingdom was the main market for the 2-to-3 million bales of cotton that slaves in North America harvested each year. Convinced “King Cotton” had dealt the Confederacy a winning hand in what had become a civil war, the secessionist government was seeking Crown recognition. Britain had banned slavery in its colonies in 1833, but some voices there were backing the Confederate cause, not only to ensure a reliable source of cotton but to rein in the United States, now bidding to compete with the United Kingdom. Arguing against that tack, economist John Elliott Cairnes of Queens College, Galway, spelled out slave societies’ failings in devastating material detail. Cairnes’ damning portrait of economic fragility, social stultification, and endemic aggression helped turn Britons against the Confederate project.

In the years approaching the Civil War, plantations in the American South had produced and stockpiled some of their biggest cotton crops ever. Confederates were hoping access to this bounty for British textile interests would spur support for the breakaway nation slaveholders had founded on a premise of White supremacy and a captive work force. Coerced workers, Cairnes countered, would never be productive at skilled tasks, nixing any hope of the Southern economy diversifying beyond agricultural labor. Cairnes cited the region’s paucity of manufacturing, a condition that forced the South to rely on finished goods from the North.

In slaveholding societies, Cairnes wrote, capital is very scarce. “From this state of things result two phenomena which may be regarded as typical of industry carried on by slaves—the magnitude of the plantations and the indebtedness of the planters,” he added. Accompanying this imbalance, he said, was a “[t]endency to a very unequal distribution of wealth.”

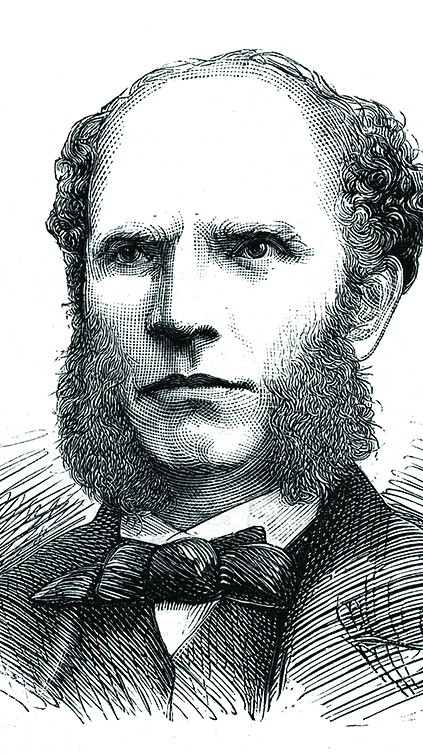

Born in 1823 at Castlebellingham, County Louth, Cairnes, son of a successful self-made brewer, earned degrees at Dublin’s Trinity College. He also read the law but gravitated to studying political structure and economic relationships and became a professor and journalist. In 1859 he met and befriended John Stuart Mill, champion of free trade and individual liberty. As Mill did, Cairnes maintained that individual freedom and personal choice brought beneficial social and economic development. These cultural characteristics had emerged only recently, and only in societies that had cast off the feudal arrangements of old Europe such as still existed in Ireland under English rule, and slavery such as powered the South’s plantations.

Instead of assuming, as many did, that slavery in the American South was bound to wither as the region’s economy developed, Cairnes laid out why slaveholders, rather than surrender land and power, inevitably would have to aggregate land and power. His 1862 book, The Slave Power, dissected the Southern economy and its poisonous effects—and struck home. Of that volume, a London paper wrote, “It will do much to arrest the extraordinary tide of sympathy with the South which the clever misrepresentations of Southern advocates have managed to set running in this country, and to imprint the picture of a modern slave-community on the imaginations of thoughtful men.”

Cairnes had become an avowed abolitionist without ever visiting the United States. He reached his conclusions by reading the works of Frederick Olmsted, Alexis de Tocqueville, and other witnesses who had traveled in the South, as well as the U.S. census and other statistical sources. His analysis emphasized not only the cruelty inflicted on the enslaved but bondage’s cost to the entire Southern economy, burdens it imposed on poor Whites as well, and its stranglehold on innovation and opportunity for all.

In the United States, Hinton Helper’s 1857 The Impending Crisis of the South had made parts of this case, stressing how slavery dominated the region’s labor market, limiting opportunities for poor Whites and discouraging industrialization. Cairnes drilled more deeply, describing how the plantation economy, mixing slavery and cotton’s chronic exhaustion of soil nutrients, drove a hunger for ever more land and ever more slaves to work that land.

“Two forces have thus been constantly urging on the Slave Power to territorial aggrandizement—the need for fresh soils, and the need for slave states…” Cairnes wrote. “Accordingly for nearly a quarter of a century—ever since the annexation of Texas—the territory at the disposal of the South has been very much greater than its available slave force has been able to cultivate; and its most urgent need has now become, not more virgin soils on which to employ its slaves, but more slaves for the cultivation of its virgin soils….”

Among impacts Cairnes cited arising from this complex was the situation in Virginia. Its soils depleted by tobacco farming, that state in effect had become a breeding center for slaves. Drawing on the 1840 and 1850 U.S. censuses, Cairnes asked what except trade in slaves shipped elsewhere in the South could explain Virginia’s population of enslaved Blacks ages 20 to 40 shrinking while the populations of enslaved Blacks in cotton-growing Louisiana, Mississippi, and Arkansas ballooned?

Cairnes also pointed to late-1850s proposals among Southern planters to revive the African slave trade. Confederate advocates claimed those overtures merely to have been explorations of ways to preserve the South’s way of life. Cairnes countered that in order to survive a slaveholding culture had to be expansive and aggressive. He painted a system benefiting an oligarchy of planters wealthy but often deeply in debt because of mortgages on enslaved workers. Scarcity of opportunity was impoverishing that society’s workers, enslaved and free. This society was not moving toward more personal freedom; its uppermost echelon needed slavery to exist.

In part thanks to Cairnes, Britain withheld recognition from the South. After the war, details of his argument came in for dispute and his analysis fell by the wayside. But his ideas on the concentration of wealth based on enslaved labor and financial links between slavery and Northern banking were prescient. Historians are rethinking Atlantic slavery’s role in capitalism’s evolution.

Cairnes remained on the faculty at University College, London, which filled classes by sex. When his health waned, Cairnes integrated his classroom, the institution’s first coed class. Arthritis and an 1872 riding accident left him partially paralyzed. He died in 1875.

Cairnes was a specialist, but The Slave Power, written for a mass readership, is an exemplar of applied economic analysis. Such work, its author felt, was neutral in nature, but could identify how an economy’s structure can yield good or bad results. Cairnes’s values shone in the middle name he and his wife gave their second son.

John Gould Cairnes’s name honored Robert Gould Shaw, the White officer who at 25 died leading U.S. Colored Troops in a valiant but failed effort to take Fort Wagner, South Carolina, on July 18, 1863.

This Cameo column appeared in the December, 2020, issue of American History.