AMERICANS WANT PRESIDENTS who are leaders—that is, special—but we also want presidents who are like us: apotheoses of averageness. So every presidential campaign sees a round of passing the bucks, with wealthy candidates explaining away their good fortune—in both senses of the word—while rivals blazon it. Sometimes hijinks ensue.

Senator Bernie Sanders (I-Vermont), the socialist who runs as a Democrat, turned out to be a millionaire. Critics pounced. “I wrote a best-selling book,” he snapped. “If you write a best-selling book, you can be a millionaire too.” Democratic front-runner Joe Biden labels himself “Middle Class Joe.” Yet he too belongs to the millionaire’s club, thanks in part to a multi-book deal. Sniffs Adam Green of the Progressive Campaign Committee: “Joe Biden is the opposite of someone who will challenge big corporate and moneyed elites.” But Green’s candidate, Senator Elizabeth Warren (D-Massachusetts), is, yes, another millionaire, thanks to her own best seller. (First novelists toiling in Brooklyn walk-ups ask, “When do I cash in?”) Though President Donald Trump would seem exempt from poor-mouthing, even he wants to be self-made, claiming he scored one scant loan from tycoon father Fred, duly repaid. Then a New York Times expose showed how, over many years, Trump père funneled multiple millions to his high-rolling son.

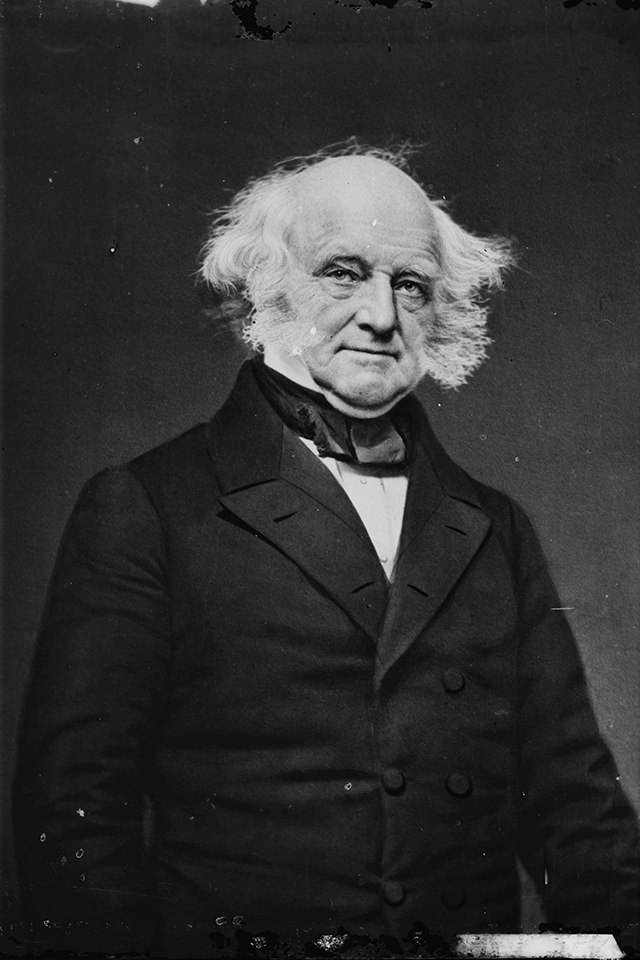

The gaudiest attack on a candidate’s wealth—detailed, vicious, hilarious—was the first. Its target: Martin Van Buren. The eighth president truly could have called himself Middle Class Martin. The great Virginians all had been to the manor born. Years of lawyering and diplomacy had made farmer’s son John Adams prosperous and cosmopolitan—qualities he passed on to son and fellow president John Quincy. Hardscrabble Andrew Jackson had struck it rich upon moving to the Mississippi Valley, then the American west. Van Buren, by contrast, grew up in Kinderhook, a Hudson Valley town whose inhabitants spoke Dutch; he’s the only president whose first language was not English.

Father Abraham was a tavernkeeper who, in Martin’s words, lacked “the spirit of accumulation.” To earn his keep, the youth had to leave school at 13. One of his first jobs was dogsbody at a law office. When young Van Buren came to work in clothes spun at home by his mother, his boss lectured him on proper appearance. The boy took two days off. When he returned, he was wearing the same outfit as his employer. Ever after, Van Buren dressed at or above his station. When he graduated from law to politics, he stumped New York in snuff-colored coat, orange cravat, pearl vest and hose, yellow kid gloves, and white trousers—unconsciously setting himself up for a world of hurt.

Van Buren the pol might have been dressing rich, but he was sticking up for New York’s common folks, who thanks to numbers—the state was the nation’s most populous by 1810—were a political bloc worth courting. As their champion and tribune, Van Buren became a power broker in the new Democratic Party. Andrew Jackson made him a protégé, first as secretary of state, then vice president. In 1836 the dapper New Yorker followed Old Hickory into the White House.

The Panic of 1837 blighted Van Buren’s term out of the gate. Banks failed. Urban mobs rioted for flour. Conditions slowly improved, but when the time came for Van Buren to stand for re-election he had two factors working hard against him.

One was his opponent, William Henry Harrison. An Indian fighter and occasional territorial governor, Harrison had a résumé that allowed his supporters to depict the candidate as a frontiersman, living in a log cabin and drinking hard cider, when in fact their man’s dad had been a Virginia planter and a signer of the Declaration of Independence. The other hazard in Van Buren’s path was a vintage Democratic Party ploy. Andrew Jackson had campaigned against John Quincy Adams for extravagance, dilating on the fact that JQA installed a billiard table at the White House. Van Buren was in line for karmic payback.

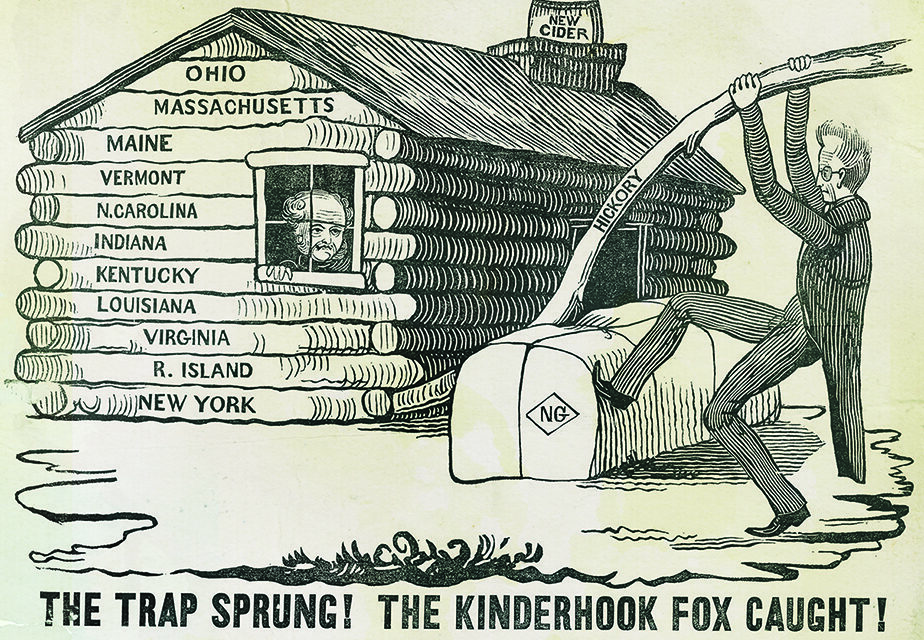

On April 14, 1840, Representative Charles Ogle (W-Pennsylvania) rose in the House to object to an appropriation for “alterations and repairs to the President’s house and furniture.” A symphony of vituperation followed. Ogle’s speech, which took three days to deliver, began with a survey of the White House grounds. The Pennsylvanian mixed facts, presented in the worst possible light, with grotesque hypotheticals. Ogle ticked off all the flowers in the White House garden, relishing the exotically named blooms: enchanter’s night-shade, adder’s tongue, lizard’s tail, false foxglove (one of Van Buren’s nicknames was the Fox of Kinderhook). Ogle then alleged that Van Buren planned to gussy up the grounds with temples, pavilions, lakes, fountains, and “two or three hundred pieces” of Italian statuary. Out of a factual survey of expenses for maintaining the White House lawn Ogle spun this fantasy: that Van Buren had “constructed a number of clever-sized hills, every pair of which, it is said, was designed to resemble and assume the form of AN AMAZON’s BOSOM, with a miniature knoll or hillock on its apex, to denote the nipple.”

Conducting his imaginary tour into what he called the “presidential palace,” Ogle visited each public room, detailing carpets, chairs, mirrors, and mantelpieces. The climax was Van Buren’s dinner table, set with gilt dessert china and sterling silver plate purchased from a Russian diplomat. “It is time,” the fabulist intoned, “the people of the United States should know that their money goes to buy for their plain, hard-handed democratic president, knives, forks and spoons of gold that he may dine in the style of the monarchs of Europe.” Worse yet, Van Buren dared own tinted glass finger cups. “What, sir, will the honest [Democrat] say to Mr. Van Buren for spending the People’s cash on FOREIGN…GREEN FINGER CUPS, in which to wash his pretty, tapering, soft, white, lily fingers, after dining on fricandeau de veau and omelette soufflé?”

Wherever possible Ogle invoked log cabins and hard cider, and the fuss the Democrats had raised over John Quincy Adams and his billiard table. “Who does not remember the indignant bursts of eloquence that were then launched forth within this Hall against gambling, waste of time, neglect of public business [and] extravagance?” Ogle beat his theme like a gong: Democrats once pretended to be simple folk; Harrison actually was; Martin Van Buren stupendously wasn’t.

Ogle published his speech far and wide. The average voter could not untangle his minutely accurate reportage on the actual White House from his lost-in-the-cosmos imaginings of how Van Buren longed to transmogrify it. However, the average voter did know that Van Buren dressed like a dude. So the muck stuck. That autumn log cabin beat green finger cups 234 electoral votes to 60. Harrison succumbed to enteric fever in April 1841, a month after his inauguration. Charles Ogle succumbed to tuberculosis that May. Van Buren marched on until 1862; omelette soufflé evidently agreed with him.

Class kabuki has breathed the longest, unto the present day, and no doubt will live as long as democracy itself. Van Buren biographer Ted Widmer laments that class warfare is dishonestly waged, as against Van Buren, by “the party of privilege.” One remedy for false class warfare might be not to practice class warfare in the first place.

Don’t count on it.