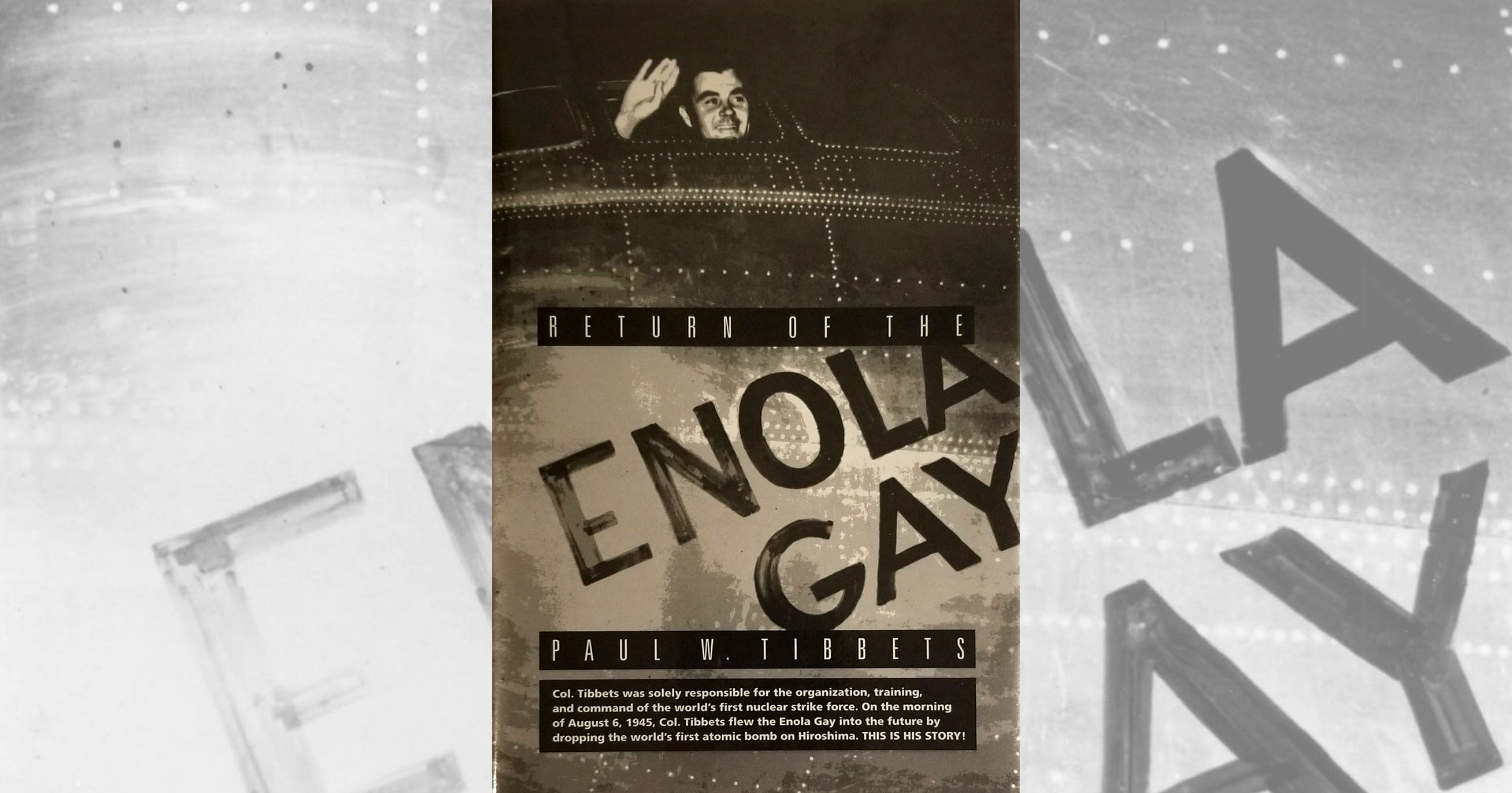

Return of the Enola Gay, by Paul W. Tibbets, Mid Coast Marketing, Columbus, Ohio, 1999, $21.95.

On August 6, 1945, a bomb burst above the Japanese city of Hiroshima, effectively bringing to an end almost 61Ž2 years of global warfare. The command pilot of the Boeing B-29 that dropped the bomb, named Enola Gay after the pilot’s mother, was 29-year-old Colonel Paul W. Tibbets. Tibbets, who had led the first American strategic bombing mission against a European target in 1942, also dropped the bomb that ended World War II.

Paul Tibbets was born in 1915, the son of a World War I Army captain. The family moved to Miami, Fla., where on Paul’s first flight he dropped Baby Ruth candy bars with small parachutes over Hialeah Racecourse. That first flight had a lifelong effect on young Paul. After graduation from a military high school (a family tradition), Paul went to college intending to become a medical doctor (also a family tradition). An aviation career proved more attractive than a medical one, however, and in 1937 Tibbets became an Aviation Cadet in order to obtain the training necessary to become a commercial pilot.

After graduation, Tibbets flew long hours towing targets and serving as General George Patton’s pilot during the 1940 Army maneuvers. With 1,000 hours’ flying time in multi-engine aircraft, Tibbets was one of the early B-17 pilots, taking the 97th Bomb Group to England in 1942. Because of his wealth of experience he was chosen to fly General Dwight D. Eisenhower to Gibraltar for the North African campaign. Tibbets remained in North Africa after that, leading bombing missions against the Germans, until he was moved up to a staff position.

After returning to the United States, Tibbets was tasked with unraveling the troubled B-29 program. Stationed at the Boeing factory, he worked with the engineers to iron out major problems in the most complex airplane built up to that time. When a high accident rate threatened the training program, Tibbets came up with the innovative idea of checking out two Women Air Force Service Pilots (WASPs) in the B-29, then sending them around to the various training fields to convince the male pilots that the plane was safe.

Tibbets, who had made more than 1,000 hours in the B-29, was given the assignment of training the men who would drop the first atomic bomb. He activated the 509th Composite Group at Wendover, Utah, where he trained his crews in the specialized requirements of dropping a 10,000-pound atomic bomb without being destroyed by the blast. When the crews were fully trained they deployed to Tinian Island in the Marianas to await the arrival of the A-bombs.

On August 6, 1945, Tibbets participated in a picture-perfect mission. When the Japanese did not immediately sue for peace, a second bomb was dropped on Nagasaki, which finally brought them to the peace table.

As Tibbets explains, when anti-nuclear radicals began to criticize the Hiroshima mission, he was overwhelmed with letters from former American soldiers and Japanese civilians who assured him that by bringing World War II to a close, he saved their lives. Various estimates credit the early end of the war with saving perhaps a half million Allied and several million Japanese lives.

After World War II Tibbets continued with the A-bomb program, witnessing the Eniwetok tests. He later took over another high-priority program, the Boeing B-47, destined to be the backbone of Strategic Air Command for 15 years. Starting with the production and training program at McConnell Air Force Base, Kan., he went on to command two B-47 wings and an air division, eventually earning his general’s star.

After retirement from the U.S. Air Force, Tibbets served as president and chief operations officer of Executive Jet Aviation Inc., an all-jet air-taxi company with headquarters in Columbus, Ohio. Soon, however, he was again forced to defend the Hiroshima mission. As the 50-year anniversary of the end of World War II approached, Enola Gay was readied for display at Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum. Political revisionists had prepared a script accusing the United States of waging a racist war of revenge against the Japanese. When the contents of the proposed text came to light, the Air Force Association, assisted by Paul Tibbets and later by members of Congress, forced the resignation of the museum director and preparation of a straightforward account of the mission.

General Tibbets tells his story well. As a former B-29 and B-47 pilot–and as one of those whose lives may have been saved by the dropping of the bomb–I highly recommend his book.