Three weeks after the June 25, 1876 fall of Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer on the Little Bighorn, two enemies—one Indian, one white— face off in mortal combat. One fires and misses; the other’s bullet finds its mark, and one of the two falls dead. In less time than it takes to tell it, the survivor scalps his foe and holds the gory trophy aloft, screaming his triumph.

Were this a Hollywood scenario, or a novel by Zane Grey or Max Brand, the victor wielding the scalping knife would be the Indian, portrayed in all his painted savagery. However, in this instance, the Indian, an obscure Cheyenne subchief named Yellow Hair, lies dead, as the white man— none other than that master showman William Frederick “Buffalo Bill” Cody— brandishes his bloody scalp. Cody will mistranslate his opponent’s name as “Yellow Hand,” and it will thus remain in most histories. What Cody screams is better that anything Hollywood could dream up—“First scalp for Custer!”

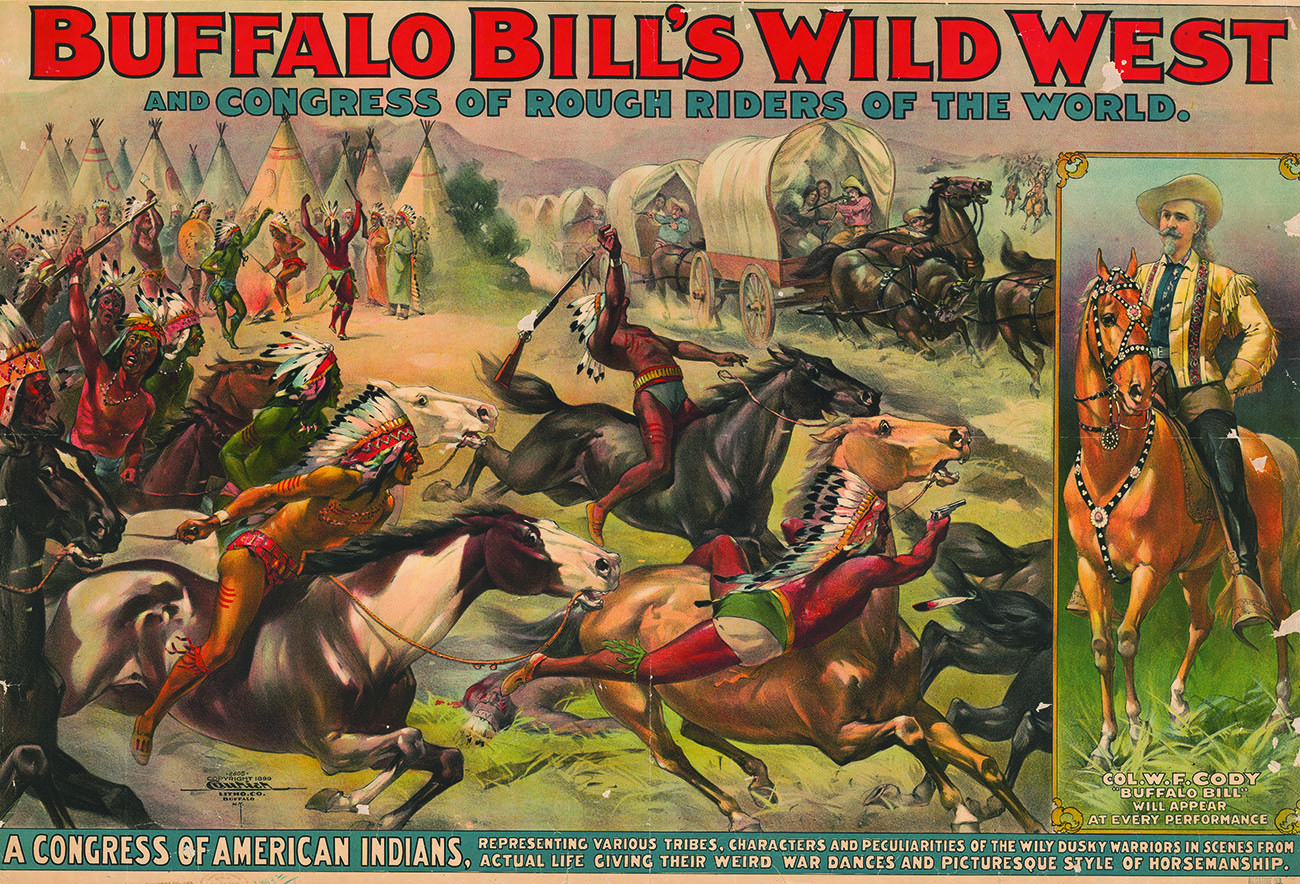

The close-quarters duel took place along Hat (or Warbonnet) Creek, in the broken hill country that defines the Wyoming-Nebraska border, and was a minor incident in Col. Wesley Merritt’s campaign to prevent several hundred Cheyennes from joining the recently victorious Crazy Horse and Sitting Bull. Accounts of the Cody–Yellow Hair fight vary greatly. Cody himself told different versions, ranging from the unbelievably theatrical (Cody was, after all, a consummate self-promoter) to one iteration in which he called the duel “Bunk! Pure bunk! For all I know, Yellow Hand died of old age.” It did, however, add color to his long career as a performer. He commissioned and starred in a play based on his most fanciful account of the duel and restaged the event—with all the trimmings—as a featured attraction in his Wild West. Cody carried the scalp with him when on tour, keeping it locked in a safe and brandishing it high during his U.S. and European reenactments.

In the end, it was neither the fight itself nor the revenge-for-Custer motive that presumably inspired it that thrilled Cody’s public; it was the act of taking his enemy’s scalp. The scalping, which Cody reenacted regularly for years, never failed to elicit cheers from the bleachers. Of course, if Yellow Hair had removed Buffalo Bill’s fine scalp that July day in 1876, the cry of indignation would have been equally loud—and Cody’s Wild West would never have seen the light of day.

Seemingly unfazed by Cody’s barbaric act, folks on the frontier were horrified when confronted with accounts of Indians scalping whites. It was, after all, a deliberate act of disfigurement. Journals and histories are rife with descriptions of the method used to accomplish the lifting of hair. The process is chillingly simple: Descending on a fallen foe— living or dead—the victor hops on his or her back, places one or both knees between the victim’s shoulders, wraps the hair around one hand and traces a circle or semicircle around the crown of the skull with his knifepoint. Using his knees for leverage, he wrenches the hair—skin and all—from the skull, often to the accompaniment of a distinct popping sound. When carried out by an experienced person, the actual deed is accomplished in a matter of seconds.Those who survived scalping described the process as unbearably painful. Adding insult to injury, scalping was permanent; as the process damaged the roots, the hair did not grow back, leaving the survivor with a large, hideous scar.

The practice of scalping was not specific to the Western frontier; it was an adjunct to Indian warfare along America’s first frontier for centuries before white men arrived. A tradition shared by many Eastern tribes, scalping served to demonstrate triumph over an enemy, as well as capture of a foe’s personal power. Soon after the whites came, it also became a path to personal enrichment, as white settlers played a role in the scalping game.

During the French and Indian War, the French (and, to a lesser extent, the English) offered bounties to their Indian allies for the scalps of their enemies. There is no doubt this radically increased the incidence of scalping along the frontier. In 1759, Maj. Robert Rogers, commander of the British allied Rogers’ Rangers, wrote of finding more than 600 scalps, “mostly English,” festooning the doorposts of the hostile Abenaki village of St. Francis (in present day Quebec, Canada). While this was doubtless a shocking sight, the Rangers and other colonial forces themselves took Indian scalps, in some cases collecting a bounty. The practice persisted, and during the Revolutionary War, Col. Daniel Brodhead—commanding part of the army sent by George Washington to neutralize the Iroquois Confederacy—submitted scalps, along with his plunder, in exchange for bounty money at campaign’s end.

Prevalent though scalping was for centuries in the East, it gained lasting historical notoriety during the Westward movement. Because of their prominent role in relocating the various Plains tribes, soldiers were prime targets for scalping. At the Little Bighorn, Custer was one of just two soldiers on the field not scalped. For years, historians and admirers claimed this was due to the regard in which his foes held him. Others speculate the victors spared Custer’s topknot because, prior to embarking on his ill-fated campaign, he’d had his hair cut short, and by then he was balding; there simply wasn’t that much scalp to take. His adjutant, W.W. Cooke, however, represented a double bounty: Cooke wore what were referred to as Dundrearies—long, flowing sideburns—and his killers scalped one cheek as well as his head.

Although popular culture has fixed the spotlight on scalping practices among the Western Indian tribes, whites were also on the hunt for Indian scalps. Starting around 1835, the Mexican government, at wit’s end after years of raids by hostiles, offered bounties on the scalps of Apaches and Comanches—men, women and children. By 1850, the scalp trade was in full swing. With bounties running as high as $200 (thousands of dollars in today’s currency) for a warrior’s scalp, the rewards were too tempting for many whites to resist. Former Forty-Niners and Texas Rangers, as well as Mexican War veterans and outlaws, rode into Mexico fairly bristling with rifles, revolvers and scalping knives. Inevitably, greed ruled; unwilling to limit themselves to the tribes proscribed by the Mexican government, some of these scalp hunters butchered peaceful Indians as well, passing their hair off as Apache or Comanche. The Apaches themselves could be big on torture but generally did not take scalps.

Whole companies of scalp hunters ranged Sonora, Chihuahua, and other Mexican states, led by some of the most dissolute men the West ever produced. Among the most notorious was John Joel Glanton, a former soldier and Texas Ranger. In 1849, Glanton led a gang of mercenaries who sold their services to the Mexican government, then expanded their activities to include taking the scalps of Mexicans and peaceful Indians. They terrorized whole Mexican villages, looting and scalping as they went. Finally, the Chihuahua government turned the tables and put a price on the heads of Glanton and his gang. They escaped to Arizona, where they were eventually killed—and scalped—by a band of vengeful Yuma Indians.

By the 1850s, the Mexican states that had offered scalp bounties were on the verge of bankruptcy, so successful—and indiscriminate—were their hired butchers. While the Mexican scalp-hunting business petered out in the 1880s, the practice of scalping remained in use through century’s end by both sides in the Indian wars.

Most Americans who grew up in the heyday of the American Western are familiar with the torments to which Indians often subjected white captives. And historically speaking, scalping was often the least horrific treatment afforded an enemy. Yet who among us didn’t secretly cheer when, in the 1956 film The Searchers, John Wayne’s Ethan Edwards emerged on horseback from the tepee of Comanche nemesis Scar, brandishing the dead chief’s scalp? Had it been Scar who rode onscreen carrying the Duke’s topknot, suffice it to say none of America’s young boys—and few of their fathers—would have slept well that night or for many nights to come.

Originally published in the June 2012 issue of Wild West.